Published online Dec 21, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i47.5391

Peer-review started: October 5, 2018

First decision: November 7, 2018

Revised: November 24, 2018

Accepted: November 30, 2018

Article in press: November 30, 2018

Published online: December 21, 2018

Processing time: 78 Days and 16.4 Hours

To increase the number of available grafts.

This is a single-center comparative analysis performed between April 1986 and May 2016. Two hundred and twelve liver transplantation (LT) were performed with donors ≥ 70 years old (study group). Then, we selected the first cases that were performed with donors < 70 years old immediately after the ones that were performed with donors ≥ 70 years old (control group).

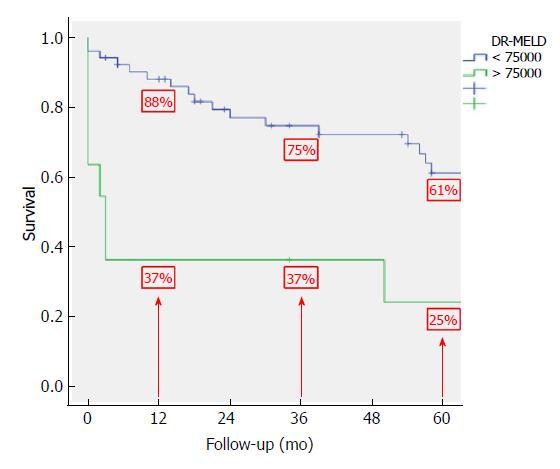

Graft and patient survivals were similar between both groups without increasing the risk of complications, especially primary non-function, vascular complications and biliary complications. We identified 5 risk factors as independent predictors of graft survival: recipient hepatitis C virus (HCV)-positivity [hazard ratio (HR) = 2.35; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.55-3.56; P = 0.00]; recipient age (HR = 1.04; 95%CI: 1.02-1.06; P = 0.00); donor age X model for end-stage liver disease (D-MELD) (HR = 1.00; 95%CI: 1.00-1.00; P = 0.00); donor value of serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (HR = 1.00; 95%CI: 1.00-1.00; P = 0.00); and donor value of serum sodium (HR = 0.96; 95%CI: 0.94-0.99; P = 0.00). After combining D-MELD and recipient age we obtained a new scoring system that we called DR-MELD (donor age X recipient age X MELD). Graft survival significantly decreased in patients with a DR-MELD score ≥ 75000, especially in HCV patients (77% vs 63% at 5 years in HCV-negative patients, P = 0.00; and 61% vs 25% at 5 years in HCV-positive patients; P = 0.00).

A DR-MELD ≥ 75000 must be avoided in order to obtain the best results in LT with donors ≥ 70 years old.

Core tip: The use of aged grafts is one of the main strategies to increase the number of available grafts. After analyzing the results of liver transplantation performed with donors ≥ 70 years old, we identified as independent predictors of graft survival: donor age X model for end-stage liver disease (D-MELD), recipient age and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. After combining D-MELD and recipient age we obtained a new scoring system that we called DR-MELD (donor age X recipient age X MELD), which seems to be a good measure to predict graft survival when using grafts ≥ 70 years old, regardless of the HCV infection.

- Citation: Caso-Maestro O, Jiménez-Romero C, Justo-Alonso I, Calvo-Pulido J, Lora-Pablos D, Marcacuzco-Quinto A, Cambra-Molero F, García-Sesma A, Pérez-Flecha M, Muñoz-Arce C, Loinaz-Segurola C, Manrique-Municio A. Analyzing predictors of graft survival in patients undergoing liver transplantation with donors aged 70 years and over. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(47): 5391-5402

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i47/5391.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i47.5391

The increase of indications for liver transplantation (LT) and the shortage of liver donors has been one of the main problems for performing LTs in the past years[1-8].

The use of aged donors is one of the main strategies to increase the number of available grafts. Spain is the country with the highest donation rate per million population (pmp) worldwide[9]. Several studies comparing Spain and the United States showed that in Spain between 1999 and 2009 there was an increase in the donation rate by the population ≥ 70 years old from 3.8 donors pmp to 8.8 donors pmp (132% increase), while in the United States this rate only increased from 1 donor pmp to 1.3 donor pmp[10,11]. Spain represents one of the countries with the most experience using aged liver grafts.

There have been multiple studies analyzing the impact of donor age on LT results since Emre et al[12] published in 1996 the first long series of LTs with donors ≥ 70 years old. Initially the results were disappointing, but as the number of LTs performed with such grafts increased, the results progressively improved until becoming comparable to those obtained with younger grafts[12-22].

The aim of the present study is to identify predictors of graft survival with the use of donors ≥ 70 years old, and formulate a score able to predict graft survival in an attempt to develop a tool for daily donor-recipient matching.

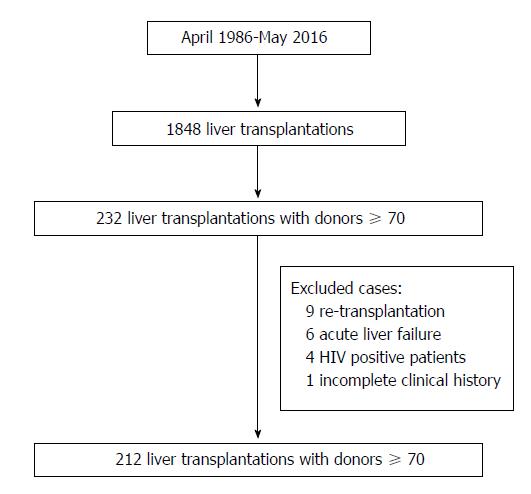

This is a single-center comparative, longitudinal and retrospective analysis of all LTs performed at the “12 de Octubre” University Hospital of Madrid between April 1986 and May 2016. During this period 1848 LTs were performed in 1659 patients. Of these, 232 (12.6%) were performed with grafts from donors ≥ 70 years old. Recipients < 18 years old, retransplantation, acute liver failure, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positivity, combined transplants, split grafts, in-vivo donation, non-heart-beating donation, LTs due to metastatic liver disease and LTs with incomplete medical records were excluded from the analysis. Thus, 212 cases (study group) were included in the study (Figure 1). To minimize the impact of the era when the LT was performed, we selected as controls the first cases that were performed with a graft < 70 years old immediately after the ones that were performed with a graft > 70 years old; thus, the control group also consisted of 212 cases.

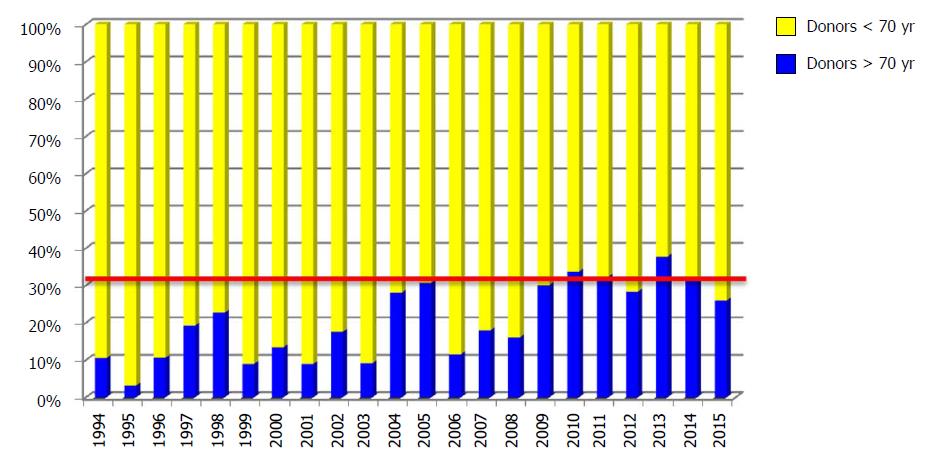

The first LT with a graft from a donor > 70 years old was performed on January 17, 1994. The use of donors ≥ 70 years old increased progressively over the years, and now stands at around 30% of all LTs performed annually in our department (Figure 2).

All donors were evaluated according to our institution’s policy and according to the Spanish National Transplant Organization’s [Organización Nacional de Trasplantes (ONT)] guidelines.

Uncontrolled active sepsis, parenteral drug addiction, untreated primary or secondary hepatobiliary disease, severe traumatic injury, untreated tumor disease (except small cutaneous carcinomas, cervical carcinoma in situ, central nervous system tumors except glioblastoma and medulloblastoma, and renal cell carcinomas < 4 cm) and severe intoxication were considered contraindications for donation.

All donors were procured with dual perfusion (aortic and portal) and all LTs were performed with cava vein preservation. End-to-end choledochal anastomosis was routinely performed. In cases of size disparity, a T-tube was used and in cases of biliary disease a cholangiojejunostomy was made.

Donor, recipient and perioperative characteristics, and post-LT complications were analyzed. Patient and graft survival were also recorded.

All grafts ≥ 70 years old were biopsied during procurement to assess the presence of steatosis. All biopsies were reviewed at the pathology department of our institution.

The presence of severe arteriosclerosis with no possibility of arterial reconstruction was considered a contraindication for the use of these grafts.

All LT recipients were evaluated before transplant in our department. The indication for LT was established according to our own policy and according to the ONT guidelines. The follow-up of each patient after the transplant was carried out based on the different protocols existing in our department.

The degree of hepatic insufficiency was evaluated with the Child-Pugh classification until 2003, and after that with the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score[23]. Refractory encephalopathy or ascites, hepatopulmonary syndrome, portopulmonary hypertension, refractory pruritus, recurrent cholangitis in patients with cholestatic liver disease, hereditary hemorrhagic teleangiectasia, polycystic disease, multiple hemangiomatosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were considered exceptions to MELD.

In all cases, an initial immunosuppressive (IMS) regimen based on the administration of a calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus or cyclosporine) and steroids was used. Other drugs (azathioprine, mycophenolate or mTOR inhibitors) were added in an individualized way depending on the clinical situation. Steroids were usually discontinued between 3 and 12 mo after LT in the cyclosporine regimen, and after 3 mo in the tacrolimus regimen.

Primary non-function (PNF) was defined as early failure of liver function manifested by signs of acute liver failure: severe hypoglycemia, persistent coagulopathy, encephalopathy III-IV, acute renal failure, severe metabolic acidosis, hemodynamic instability and abnormal hepatic enzyme levels.

Acute rejection episodes were classified based on the Banff grades[24]. The initial treatment was based on the degree of rejection. Grade 1 rejections were treated by increasing the dose of IMS drugs, and grade 2 and 3 rejections were treated with 1 g of methylprednisolone intravenously for 3 d and steroid recycling. Corticosteroid-refractory rejections were treated with monoclonal antibodies: ATG and OKT3 in the initial period, and with thymoglobulin and basiliximab thereafter.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) recurrence in the graft was confirmed by histology based on the presence of periportal and lobular inflammation and the presence of fibrosis[25]. In our department, we do not have a biopsy follow-up protocol for HCV-patients undergoing LT, and therefore biopsies were only performed in the presence of elevated hepatic enzymes in the absence of abnormal vascular, biliary and IMS levels.

Vascular complications were defined as all post-transplant abnormalities in the hepatic artery, portal vein or cava vein requiring therapeutic procedures such as radiological or surgical procedures.

Biliary complications were defined as all post-transplant abnormalities in the biliary tree requiring radiological, endoscopic or surgical procedures.

In order to carry out the graft survival analysis, we took into account the number of months from the LT day to the day on which one of the following events occurred: (1) end of study (August 31, 2016), (2) death, (3) loss of follow-up, or (4) re-transplantation. When the patient died, the graft was considered as non-functioning graft.

Statistical analysis was done using the SPSS software package, version 20.0.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation with a normal distribution of the variable, and as median and interquartile range when the variable did not have a normal distribution. Qualitative variables were expressed as absolute frequencies (n) and relative frequencies (%). To compare qualitative variables, the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used. To compare quantitative variables with qualitative variables, Student’s t-test was used. Non-parametric tests were employed when appropriate. Graft survival was studied using the Kaplan-Meier method and comparisons between the different curves obtained were performed using the log-rank test. Regarding the multivariate analysis, we considered those variables in which statistically significant differences were found during the comparative analysis and those that we considered clinically relevant. The multivariate Cox proportional hazard model was applied to analyze the prognostic value for the risk of graft loss in all LTs performed with donors ≥ 70 years old. A stepwise backward conditional procedure was used. Finally, based on the results obtained, we studied graft survival according to the risk factors identified during the multivariate analysis. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all studies performed.

The donor characteristics are shown in Table 1. Aged donors were predominantly female whereas younger donors were predominantly male (P = 0.00). Obesity (27% vs 16%; P = 0.00), hypertension (58% vs 26%; P = 0.00) and diabetes (20% vs 7%; P = 0.00) were more common among aged donors. Although we found more cases of cerebrovascular deaths in the study group (81% vs 51%; P = 0.06), this difference was not statistically significant. Cardiac arrest was significantly lower in donors ≥ 70 years old (7% vs 25%; P = 0.00). Median serum sodium level was high in both groups, but significantly lower in the study group. Median serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (GPT) and glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT) levels were normal in both groups but, like sodium levels, they were significantly lower in aged donors. Biopsy findings were similar in both groups, with more than half of all cases without steatosis in each group.

| Donors < 70 years old (n = 212) | Donors ≥ 70 years old (n = 212) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 47 (26) | 76 (7) | 0.00 |

| Gender (male/female) | 139/73 (65.6/34.3) | 87/125 (41.0/59.0) | 0.00 |

| BMI ≥ 30 (kg/m2) | 33 (15.6) | 57 (27.3) | 0.00 |

| Cause of death | |||

| Trauma | 72 (34.0) | 32 (15.1) | |

| Cerebrovascular | 108 (50.9) | 172 (81.1) | 0.06 |

| Other | 32 (15.1) | 8 (3.8) | |

| History of hypertension | 55 (25.9) | 122 (57.5) | 0.00 |

| History of diabetes | 14 (6.6) | 43 (20.3) | 0.00 |

| ICU stay (h) | 48 (24-96) | 211 (24-48) | 0.00 |

| Cardiac arrest | 53 (25.0) | 14 (6.6) | 0.00 |

| Hemodynamic instability | 68 (32.1) | 60 (28.3) | 0.39 |

| Vasopressor use | 173 (81.6) | 159 (75.0) | 0.09 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 145 (63) | 156 (69) | 0.00 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.5) | 0.8 (0.3) | 0.24 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 148 (12) | 145 (11) | 0.00 |

| GOT (IU/L) | 39 (55) | 28 (19) | 0.00 |

| GPT (IU/L) | 27 (53) | 20 (17) | 0.00 |

| Biopsy findings | |||

| Normal | 125 (57.8) | 107 (49.8) | |

| Microsteatosis | 26 (12.6) | 41 (19.5) | |

| Mild macrosteatosis (< 30%) | 54 (26.1) | 56 (26.7) | 0.12 |

| Moderate macrosteatosis (30%-60%) | 7 (3.5) | 7 (3.5) | |

| Severe macrosteatosis (≥ 60%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) |

Table 2 lists recipient characteristics of the 2 groups. Mean recipient age was higher in recipients of older grafts. HCV-positivity was more common among patients undergoing LT with younger donors (34% vs 49%; P = 0.00). Median product of donor age and preoperative MELD (D-MELD) value was higher in the recipients of the study group (1051 vs 629; P = 0.00), but all laboratory parameters analyzed were similar in both groups.

| Donors < 70 years old (n = 212) | Donors ≥ 70 years old (n = 212) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 54 (14) | 59 (13) | 0.00 |

| Gender (male/female) | 161/51 (75.9/24.1) | 167/45 (78.8/21.2) | 0.48 |

| Cirrhosis | |||

| Alcoholic | 61 (28.8) | 95 (44.8) | |

| HBV | 13 (6.1) | 24 (11.3) | 0.00 |

| HCV | 105 (49.5) | 72 (34.0) | |

| Other | 33 (15.6) | 21 (9.9) | |

| HCC | 82 (38.7) | 84 (39.3) | 0.89 |

| Child-Pugh | |||

| A | 47 (22.1) | 46 (21.7) | |

| B | 75 (35.4) | 89 (42) | 0.22 |

| C | 90 (42.5) | 77 (36.3) | |

| MELD | 15 (8) | 13 (5) | 0.20 |

| MELD-Na | 16 (11) | 14 (9) | 0.12 |

| D-MELD | 629 (475) | 1051 (842) | 0.00 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 107 (44) | 105 (48) | 0.70 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.07 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.7 (3.4) | 1.9 (2.4) | 0.10 |

| GOT (IU/L) | 54 (67) | 58 (58) | 0.77 |

| GPT (IU/L) | 40 (49) | 37 (43) | 0.60 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 3.3 (0.9) | 3.4 (1.0) | 0.77 |

| Prothrombin activity (%) | 62 ± 20 (11.8-120) | 65 ± 18 (5-119) | 0.07 |

| Platelets (n) | 77900 (54925) | 82500 (60250) | 0.16 |

| UNOS | |||

| ICU | 0 | 3 (1.4) | 0.77 |

| Hospital | 17 (8) | 12 (5.7) | |

| Home | 195 (92) | 197 (92.9) |

Table 3 shows perioperative characteristics in the 2 groups. Mean cold ischemia time (CIT) was longer in the study group (445 min vs 386 min; P = 0.00). This is because most aged donors were from hospitals outside of Madrid, and in some cases, it took up to 3 h for the grafts to reach our hospital. Transfusion requirements were similar in both groups and no differences were observed in the immunosuppresive treatment.

| Donors < 70 years old (n = 212) | Donors ≥ 70 years old (n = 212) | P value | |

| CIT (min) | 386 ± 168 (100-1038) | 445 ± 158 (60-975) | 0.00 |

| WIT (min) | 64 ± 17 (40-200) | 61 ± 13 (30-130) | 0.04 |

| Transfusional requeriments | |||

| RBC (U) | 6 (3-10) | 5 (3-10) | 0.98 |

| FFP (U) | 12 ± 9 (0-60) | 13 ± 9 (0-58) | 0.40 |

| Platelets (U) | 3 ± 3 (0-37) | 3 ± 3 (0-16) | 0.53 |

| Basal immunosuppressant drugs | |||

| Cyclosporine plus steroids | 33 (15.6) | 30 (14.3) | 0.71 |

| Tacrolimus plus steroids | 179 (84.4) | 180 (85.7) | |

| ICU stay (d) | 4 (2-5) | 4 (2-6) | 0.58 |

| Hospital stay (d) | 18 ± 17 (0-105) | 16 ± 12 (0-83) | 0.34 |

| Primary non-function | 6 (2.8) | 7 (3.3) | 0.24 |

| Acute rejection | 61 (28.8) | 53 (25.1) | 0.39 |

| Infectious complications | 56 (26.4) | 41 (19.3) | 0.08 |

| Medical complications | 90 (42.5) | 93 (43.9) | 0.76 |

| Surgical complications | 38 (17.9) | 34 (16) | 0.60 |

| Vascular complications | 11 (5.2) | 14 (6.6) | 0.80 |

| Biliary complications | 24 (11.3) | 11 (5.2) | 0.41 |

| Reoperation | 27 (12.7) | 20 (9.4) | 0.28 |

| De novo tumors | 24 (11.3) | 22 (10.4) | 0.57 |

| HCV recurrence | 73 (61.9) | 42 (57.5) | 0.55 |

| Days | 141 (58-535) | 148 (51-316) | 0.90 |

| Hepatitis F3 or F4 | 18 (24.7) | 21 (50) | 0.00 |

| Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis | 7 (9.6) | 7 (16.7) | 0.26 |

| Re-transplantation | 11 (5.2) | 12 (5.7) | 0.83 |

In Table 3 we can also observe the differences between the 2 groups regarding the development of different complications. Hospital stay in both intensive care unit (ICU) and conventional hospitalization unit were similar in both groups. No differences were found in relation to PNF, and acute rejection rate was similar in both groups (25% vs 29%; P = 0.39). Infectious complications were lower in the study group, but differences were not statistically significant. The rate of vascular complications was similar in both groups (6.6% vs 5.2%; P = 0.80). Although biliary complications were lower in the group of LTs performed with aged donors, differences were not statistically significant (5.2% vs 11.3%; P = 0.41). Finally, HCV recurrence was similar in both groups, but severe HCV recurrence (F3-F4 hepatitis) was higher in the study group (50% vs 25%; P = 0.00).

After a mean follow-up of 67 ± 59 (range: 0-271) mo in the control group and a mean follow-up of 67 ± 61 (range: 0-269) mo in the study group, there were 67 (31.6%) deaths in the control group and 80 (37.7%) deaths in the study group. These differences were not statistically significant.

We also did not observe significant differences between the causes of death in each group, and the main causes in both groups were infections and medical complications.

Patient survival at 1, 3 and 5-years was 86.3%, 79.8% and 72.8%, respectively, in the control group and 83.8%, 78.1% and 69%, respectively, in the study group. Differences between the groups were not significant.

Graft survival at 1, 3 and 5-years was 85.3%, 78.4% and 70.2%, respectively, in the control group and 80.5%, 73.6% and 64.5%, respectively, in the study group. Again, differences between the groups were not significant.

A Cox-regression analysis to investigate risk factors for graft loss in LTs performed with donors ≥ 70 years old was performed including all variables where we found differences during the comparative analysis and the ones that we considered clinically relevant. Table 4 shows the results. We identified 5 risk factors as independent predictors of graft survival: recipient HCV-positivity [hazard ratio (HR) = 2.35; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.55-3.56; P = 0.00]; recipient age (HR = 1.04; 95%CI: 1.02-1.06; P = 0.00); D-MELD (HR = 1.00; 95%CI: 1.00-1.00); donor value of serum GPT (HR = 1.00; 95%CI: 1.00-1.00; P = 0.00); and donor value of serum sodium (HR = 0.96; 95%CI: 0.94-0.99; P = 0.00).

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Donor age | 1.23 (0.90-1.68) | 0.19 | 1.15 (0.73-1.81) | 0.52 |

| Female donor | 1.08 (0.78-1.49) | 0.63 | ||

| Donor BMI | ||||

| 25-29 | 1.56 (1.05-2.31) | 0.08 | ||

| ≥ 30 | 1.53 (0.95-2.47) | 0.07 | ||

| Cause of death | ||||

| Cerebrovascular | 1.091 (0.75-1.58) | 0.65 | ||

| Others | 0.68 (0.34-1.36) | 0.28 | ||

| Donor history of hypertension | 1.53 (1.10-2.12) | 0.00 | 1.43 (0.97-2.12) | 0.07 |

| Donor history of diabetes | 0.99 (0.62-1.58) | 0.97 | ||

| Donor ICU stay | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | 0.37 | ||

| Donor cardiac arrest | 0.94 (0.59-1.52) | 0.82 | ||

| Donor last serum sodium level | 0.97 (0.96-0.99) | 0.01 | 0.96 (0.94-0.99) | 0.00 |

| Donor last serum GOT | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.13 | ||

| Donor last serum GPT | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.02 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.00 |

| Biopsy findings | ||||

| Normal | 1.00 (0.64-1.59) | 0.96 | ||

| Microsteatosis | 1.22 (0.82-1.82) | 0.31 | ||

| Mild macrosteatosis (< 30%) | 1.89 (0.93-3.82) | 0.07 | ||

| Moderate macrosteatosis (30%-60%) | 0.93 (0.57-1.53) | 0.78 | ||

| Recipient age | 1.03 (1.01-1.05) | 0.00 | 1.04 (1.02-1.06) | 0.00 |

| HCV+ recipient | 1.82 (1.32-2.50) | 0.00 | 2.35 (1.55-3.56) | 0.00 |

| HCC presence | 1.24 (0.90-1.71) | 0.18 | ||

| MELD | 1.03 (1.00-1.06) | 0.05 | ||

| D-MELD | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.00 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.00 |

| Prothrombin activity | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.28 | ||

| CIT | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | 0.13 | ||

| WIT | 1.01 (0.99-1.02) | 0.38 | ||

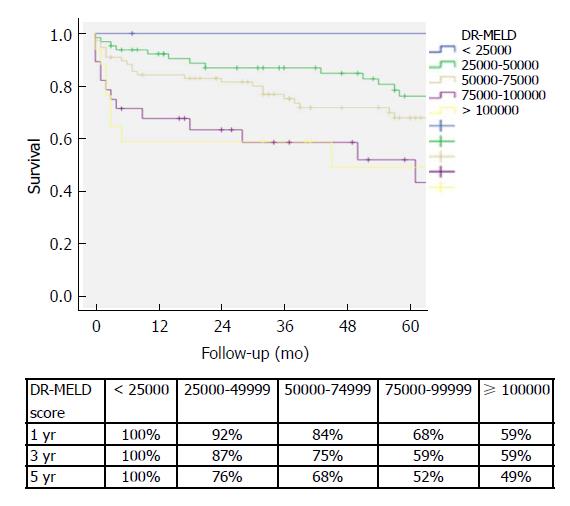

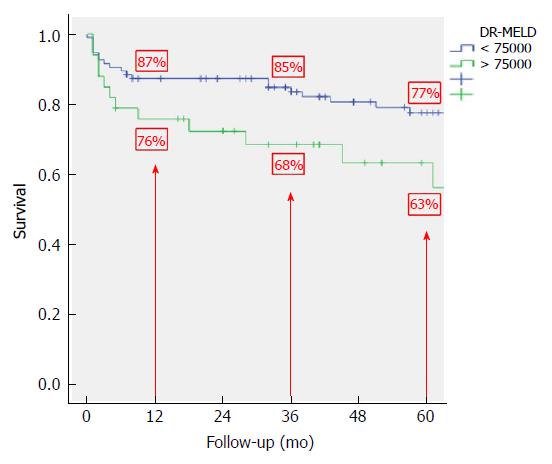

After combining D-MELD and recipient age we obtained a new scoring system that we called DR-MELD (product of donor age, recipient age and preoperative MELD). Median (interquartile range) DR-MELD in the study group was 58309 (27861). We stratified the recipients into 5 groups (DR-MELD < 25000; DR-MELD 25000-49999; DR-MELD 50000-74999; DR-MELD 75000-99999; and DR-MELD ≥ 100000), and we analyzed the graft survival according to this new score. Figure 3 shows the results. Overall, we obtained a graft survival of more than 70% at 5 years in patients with a DR-MELD score ≤ 75000, and of less than 50% in patients with a DR-MELD score ≥ 75000. Finally, we calculated graft survival according to DR-MELD and HCV infection status, and we observed that graft survival significantly decreased in patients with a DR-MELD score ≥ 75000, especially in HCV-positive patients (77% vs 63% at 5 years in HCV-negative patients, P = 0.00; and 61% vs 25% at 5 years in HCV-positive patients; P = 0.00) (Figures 4 and 5).

Use of elderly donors is an effective mean to expand the donor pool with results similar to those described with the use of younger donors, as demonstrated in multiple studies over the past years[12-22,26].

In Europe, the use of these donors has become common. One single-center study reports that almost 40% of all LTs were performed with donors ≥ 70 years old[26]. However, in the United States, the use of these grafts is lower than in Europe, as shown in a recent study, where the rate of LTs performed with donors ≥ 70 years old in the United States was only 4.3% between January 2002 and September 2014[27].

According to the literature, and also as observed in the present study, elderly donors have a number of common characteristics[12-22,26]. Females predominate over males. The rates of hypertension and diabetes are also higher among these donors. The main cause of donor death is the cerebrovascular accident, followed by trauma (81% vs 15%). Finally, there is a tendency to minimize other donor risk factors for a worse evolution[28]. Thus, older donors have shorter ICU stays with fewer episodes of hemodynamic instability or cardiac arrest, and laboratory parameters such as serum sodium and transaminases are usually significantly lower.

In the literature, different factors have been described as predictors of graft survival, and most of them have been reported in several studies[8,13,26,29-33]. A summary of predictors of graft survival with the use of donors ≥ 70 years old that were identified by multivariate analysis (Cox regression), is shown in Table 5. In our study, we identified 5 independent predictors of graft survival: donor serum sodium and serum GPT, recipient age, HCV and D-MELD.

| Author | Country | n | Donor age | Donor diabetes | Donor GPT | Donor Na | Recipient age | Recipient BMI | UNOS | HCV positive | MELD | D-MELD | BAR | CIT | Period | Renal replacement |

| Segev, 2007 | United States | 1043 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Cescon, 2008 | Italy | 152 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Jimenez Romero, 2013 | Spain | 50 | X | |||||||||||||

| Cepeda Franco, 2016 | Spain | 423 | X | |||||||||||||

| Bertuzzo, 2017 | Italy | 278 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Montenovo, 2017 | United States | 1749 | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Ghinolfi, 2017 | Italy | 515 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Present study, 2018 | Spain | 212 | X | X | X | X | X |

Sodium and GPT are laboratory parameters that in many studies have been identified as risk factors for a poor outcome, regardless of the age of the donor[28]. However, in studies performed with donors ≥ 70 years old they never were found to be predictors of graft survival[8,13,26,30-33]. In addition, although differences between these parameters were statistically significant in our study, we think that they are not clinically relevant since they were within the normal range in both groups.

HCV is a long-known survival predictor in LTs performed with aged donors. HCV recurrence is earlier and more aggressive when aged donors are used[34-38]. In most of the studies performed with donors older than 70 years, we also observed that HCV was an independent predictor of graft survival[13,26,30-32]. In recent years, younger grafts usually have been implanted in HCV-positive patients, while older livers were used to transplant patients with HCC and without HCV infection[30]. Currently, with the arrival of direct-acting antivirals (DAA), the results of LT with aged donors in HCV patients have changed and donor age will not influence anymore LT results in HCV recipients.

It has been demonstrated that D-MELD is able to predict the results of LTs with donors older than 70 years, especially in HCV patients[31,39]. Initially, Halldorson et al[40] proposed a D-MELD score of 1600 as a cut-off point to identify cases with significantly worse outcomes. In our study, these results were not confirmed when they were applied to recipients of grafts ≥ 70 years old, since we obtained a 5-year graft survival of 68.4% and 62.1% for D-MELD scores < 1600 and ≥ 1600, respectively (P > 0.05). We also did not obtain significant differences when we used different cut-off points proposed by other authors[31,39], or by applying still different ones. Although D-MELD was an independent predictor of graft survival in our study, we think that it should be used in combination with other parameters to improve its prediction power.

The age of the recipient is another parameter that in many studies has been linked with the result. In multiple series of LT with donors ≥ 70 years old, recipient age was an independent predictor of graft survival[30,33]. Some authors proposed that these grafts should be limited to young recipients without other associated risk factors to obtain better results[30,41,42]. However, in recent studies[13,26,31] the mean age of the recipients was even higher in the group of transplants performed with elderly donors than in the group of transplants performed with younger donors.

In our study, other variables such as CIT, donor body mass index (BMI) and graft steatosis did not show a predictive value of graft survival (Table 4). However, we observed in the univariate analysis that the hazard ratio increased as the donor BMI and the steatosis percentage increased. Based on this observation and on an analysis of the results obtained by other authors[30,43], we consider that the presence of steatosis ≥ 30% should be a contraindication for the use of these grafts. A graft biopsy should be mandatory to assess the presence of steatosis and it should always be done during the evaluation of an aged donor. More detailed studies are probably necessary to determine what percentage of steatosis should be the maximum recommended when using elderly grafts. Finally, CIT is a risk factor that has been related with a worse graft survival, and multiple studies recommend that it must be less than 8 hours when a graft ≥ 70 years old is used[8,26,30]. In our study, CIT was not an independent predictor of graft survival. This is probably because the mean CIT in the study group was 445 min, less than the 8 h recommended by most groups. We think, like other authors, that CIT should be as short as possible when aged grafts are going to be used, although a longer CIT should not be an absolute contraindication to use such grafts, and that this parameter must be analyzed case by case.

After analyzing the results of the multivariate analysis, we formulated a score using the D-MELD in combination with the age of the recipient (DR-MELD), and we analyzed its ability to predict graft survival in the study group according to the presence or absence of the HCV. We did not use serum donor GPT and sodium because, as we have previously seen, they were not clinically relevant. Overall, 5-year graft survival with donors ≥ 70 years old with a DR-MELD score < 75000 was 72%, while with a DR-MELD score ≥ 75000 it decreased to 53% (P = 0.00). Furthermore, with a DR-MELD score ≥ 75000, 5-year graft survival decreased significantly in HCV-negative patients (77% vs 63%, P = 0.00), but it decreased more significantly in HCV-positive patients (61% vs 25%, P = 0.00). Currently, with the effectiveness of the DAA, we can use an aged donor in a HCV-positive recipient with the same results than in a HCV-negative recipient. Given these results, DR-MELD seems to be a good measure to predict graft survival when using grafts ≥ 70 years old.

The present study is a single-center and longitudinal study, which ensures the homogeneity of the sample, the surgical technique and the follow-up. Furthermore, the fact that it is a single-center study and not based on a registry database has allowed the analysis of multiple variables of both donors and recipients. On the other hand, the study is retrospective and there is an important time difference between the first cases and the last ones; this may have a significant influence on the results, as other authors have noted[32]. Further studies are required to validate our results and compare them with other scores described in the literature, to define which of them is the most accurate.

In conclusion, the use of donors ≥ 70 years old is a safe strategy to expand the donor pool, and in the coming years they will probably become the main source of donation in western countries. Graft and patient survivals are similar to those obtained with the use of younger grafts without increasing the risk of complications, especially PNF, vascular complications and biliary complications. A DR-MELD ≥ 75000 must be avoided in order to obtain the best results. More studies are required to validate these findings.

The increased life expectancy of the general population makes that donor age should also increase to ensure the number of available donors. Concerns regarding the use of aged organs are the perception of greater susceptibility to ischemic damage resulting in higher risk of initial poor function or primary non-function. There are limited published data evaluating results of liver transplantation (LT) with these donors and only a few of them try to identify predictors of graft survival.

Some authors have suggested that if we identify which variables are able to predict survival, careful donor to recipient matching could avoid some complications after LT with aged donors and improve patient and graft survival.

The main objective of our study is to evaluate LT outcomes with donors ≥ 70 years old using a large single-center cohort, identify predictors of graft survival and compare our results with previously published.

We analyzed all LT performed at our department between April 1986 and May 2016 with donors ≥ 70 years old, then we compared the outcomes with those obtained using younger donors in the same period and finally a multivariate Cox proportional hazard model was applied to analyze the prognostic value for the risk of graft loss in all LT performed with aged donors.

The use of donors ≥ 70 years old is a safe strategy to expand the donor pool. Graft and patient survivals are similar to those obtained with the use of younger grafts without increasing the risk of complications, especially primary non-function, vascular complications and biliary complications. We identified 5 independent predictors of graft survival: donor serum sodium and serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase, recipient age, hepatitis C virus (HCV) and donor age X model for end-stage liver disease (D-MELD). Finally, we formulated a score using the D-MELD in combination with the age of the recipient (we called it DR-MELD), and we analyzed its ability to predict graft survival in the study group according to the presence or absence of the HCV. A DR-MELD < 75000 was a good measure to predict graft survival when using grafts ≥ 70 years old regardless the presence of HCV.

The use of aged donors in LT is not associated with higher primary non-function or other complications if we perform a careful donor selection. The current study emphasizes on the importance of identifying predictors of graft survival before donor to recipient matching. With the arrival of direct-acting antivirals, the results of LT with aged donors in HCV patients have changed and donor age will not influence anymore LT results in HCV recipients. Donor age, recipient age, MELD, cold ischemia time and the presence of steatosis seems to be the best predictors of graft survival after analyze the outcomes of several studies.

The use of aged donors is a safe alternative to expand the donor pool in LT with brain death donors. Additional studies are needed to investigate if the donor age could also be increased with marginal donors such as non-heart beating, split or living donors.

The authors want to thank all members of the HBP surgery and Abdominal Organs Transplantation Unit for their contributions to this valuable resource.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Mikulic D, Nah YW S- Editor: Ma RY L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Memoria Trasplante Hepático. Accessed October 4, 2018. Available from: http://www.ont.es/infesp/Memorias/Memoria%20Hepático%202016.pdf. |

| 2. | Strasberg SM, Howard TK, Molmenti EP, Hertl M. Selecting the donor liver: risk factors for poor function after orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1994;20:829-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 422] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Adam R, Sanchez C, Astarcioglu I, Bismuth H. Deleterious effect of extended cold ischemia time on the posttransplant outcome of aged livers. Transplant Proc. 1995;27:1181-1183. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Ureña MA, Ruiz-Delgado FC, González EM, Segurola CL, Romero CJ, García IG, González-Pinto I, Gómez Sanz R. Assessing risk of the use of livers with macro and microsteatosis in a liver transplant program. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:3288-3291. [PubMed] |

| 5. | López-Navidad A, Caballero F. Extended criteria for organ acceptance. Strategies for achieving organ safety and for increasing organ pool. Clin Transplant. 2003;17:308-324. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Busuttil RW, Tanaka K. The utility of marginal donors in liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:651-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 520] [Cited by in RCA: 497] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cuende N, Grande L, Sanjuán F, Cuervas-Mons V. Liver transplant with organs from elderly donors: Spanish experience with more than 300 liver donors over 70 years of age. Transplantation. 2002;73:1360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jiménez-Romero C, Clemares-Lama M, Manrique-Municio A, García-Sesma A, Calvo-Pulido J, Moreno-González E. Long-term results using old liver grafts for transplantation: sexagenerian versus liver donors older than 70 years. World J Surg. 2013;37:2211-2221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Matesanz R, Domínguez-Gil B, Coll E, Mahíllo B, Marazuela R. How Spain Reached 40 Deceased Organ Donors per Million Population. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:1447-1454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Halldorson J, Roberts JP. Decadal analysis of deceased organ donation in Spain and the United States linking an increased donation rate and the utilization of older donors. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:981-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chang GJ, Mahanty HD, Ascher NL, Roberts JP. Expanding the donor pool: can the Spanish model work in the United States? Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1259-1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Emre S, Schwartz ME, Altaca G, Sethi P, Fiel MI, Guy SR, Kelly DM, Sebastian A, Fisher A, Eickmeyer D. Safe use of hepatic allografts from donors older than 70 years. Transplantation. 1996;62:62-65. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Cescon M, Mazziotti A, Grazi GL, Ravaioli M, Pierangeli F, Ercolani G, Cavallari A. Evaluation of the use of graft livers procured from old donors (70 to 87 years) for hepatic transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:934-935. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Gastaca M, Valdivieso A, Pijoan J, Errazti G, Hernandez M, Gonzalez J, Fernandez J, Matarranz A, Montejo M, Ventoso A. Donors older than 70 years in liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:3851-3854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim DY, Cauduro SP, Bohorquez HE, Ishitani MB, Nyberg SL, Rosen CB. Routine use of livers from deceased donors older than 70: is it justified? Transpl Int. 2005;18:73-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nardo B, Masetti M, Urbani L, Caraceni P, Montalti R, Filipponi F, Mosca F, Martinelli G, Bernardi M, Daniele Pinna A. Liver transplantation from donors aged 80 years and over: pushing the limit. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1139-1147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fouzas I, Sgourakis G, Nowak KM, Lang H, Cicinnati VR, Molmenti EP, Saner FH, Nadalin S, Papanikolaou V, Broelsch CE. Liver transplantation with grafts from septuagenarians. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:3198-3200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cescon M, Grazi GL, Cucchetti A, Ravaioli M, Ercolani G, Vivarelli M, D’Errico A, Del Gaudio M, Pinna AD. Improving the outcome of liver transplantation with very old donors with updated selection and management criteria. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:672-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Faber W, Seehofer D, Puhl G, Guckelberger O, Bertram C, Neuhaus P, Bahra M. Donor age does not influence 12-month outcome after orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:3789-3795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sampedro B, Cabezas J, Fábrega E, Casafont F, Pons-Romero F. Liver transplantation with donors older than 75 years. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:679-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cascales Campos P, Ramírez P, Gonzalez R, Domingo J, Martínez Frutos I, Sánchez Bueno F, Robles R, Miras M, Pons JA, Parrilla P. Results of liver transplantation from donors over 75 years: case control study. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:683-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Darius T, Monbaliu D, Jochmans I, Meurisse N, Desschans B, Coosemans W, Komuta M, Roskams T, Cassiman D, van der Merwe S. Septuagenarian and octogenarian donors provide excellent liver grafts for transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:2861-2867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wiesner R, Edwards E, Freeman R, Harper A, Kim R, Kamath P, Kremers W, Lake J, Howard T, Merion RM. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) and allocation of donor livers. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:91-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1825] [Cited by in RCA: 1865] [Article Influence: 84.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Banff schema for grading liver allograft rejection: an international consensus document. Hepatology. 1997;25:658-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1016] [Cited by in RCA: 1002] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Sreekumar R, Gonzalez-Koch A, Maor-Kendler Y, Batts K, Moreno-Luna L, Poterucha J, Burgart L, Wiesner R, Kremers W, Rosen C. Early identification of recipients with progressive histologic recurrence of hepatitis C after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2000;32:1125-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ghinolfi D, Lai Q, Pezzati D, De Simone P, Rreka E, Filipponi F. Use of Elderly Donors in Liver Transplantation: A Paired-match Analysis at a Single Center. Ann Surg. 2018;268:325-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Halazun KJ, Rana AA, Fortune B, Quillin RC 3rd, Verna EC, Samstein B, Guarrera JV, Kato T, Griesemer AD, Fox A, Brown RS Jr, Emond JC. No country for old livers? Examining and optimizing the utilization of elderly liver grafts. Am J Transplant. 2018;18:669-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bruzzone P, Giannarelli D, Adam R; European Liver and Intestine Transplant Association; European Liver Transplant Registry. A preliminary European Liver and Intestine Transplant Association-European Liver Transplant Registry study on informed recipient consent and extended criteria liver donation. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:2613-2615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ghinolfi D, De Simone P, Lai Q, Pezzati D, Coletti L, Balzano E, Arenga G, Carrai P, Grande G, Pollina L. Risk analysis of ischemic-type biliary lesions after liver transplant using octogenarian donors. Liver Transpl. 2016;22:588-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Segev DL, Maley WR, Simpkins CE, Locke JE, Nguyen GC, Montgomery RA, Thuluvath PJ. Minimizing risk associated with elderly liver donors by matching to preferred recipients. Hepatology. 2007;46:1907-1918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Cepeda-Franco C, Bernal-Bellido C, Barrera-Pulido L, Álamo-Martínez JM, Ruiz-Matas JH, Suárez-Artacho G, Marín-Gómez LM, Tinoco-González J, Díaz-Aunión C, Padillo-Ruiz FJ. Survival Outcomes in Liver Transplantation With Elderly Donors: Analysis of Andalusian Transplant Register. Transplant Proc. 2016;48:2983-2986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Bertuzzo VR, Cescon M, Odaldi F, Di Laudo M, Cucchetti A, Ravaioli M, Del Gaudio M, Ercolani G, D’Errico A, Pinna AD. Actual Risk of Using Very Aged Donors for Unselected Liver Transplant Candidates: A European Single-center Experience in the MELD Era. Ann Surg. 2017;265:388-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Montenovo MI, Hansen RN, Dick AAS, Reyes J. Donor Age Still Matters in Liver Transplant: Results From the United Network for Organ Sharing-Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients Database. Exp Clin Transplant. 2017;15:536-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Berenguer M, López-Labrador FX, Wright TL. Hepatitis C and liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2001;35:666-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Boin IF, Ataide EC, Leonardi MI, Stucchi R, Sevá-Pereira T, Pereira IW, Cardoso AR, Caruy CA, Luzo A, Leonardi LS. Elderly donors for HCV(+) versus non-HCV recipients: patient survival following liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:792-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lake JR, Shorr JS, Steffen BJ, Chu AH, Gordon RD, Wiesner RH. Differential effects of donor age in liver transplant recipients infected with hepatitis B, hepatitis C and without viral hepatitis. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:549-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Mutimer DJ, Gunson B, Chen J, Berenguer J, Neuhaus P, Castaing D, Garcia-Valdecasas JC, Salizzoni M, Moreno GE, Mirza D. Impact of donor age and year of transplantation on graft and patient survival following liver transplantation for hepatitis C virus. Transplantation. 2006;81:7-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | García-Reyne A, Lumbreras C, Fernández I, Colina F, Abradelo M, Magan P, San-Juan R, Manrique A, López-Medrano F, Fuertes A. Influence of antiviral therapy in the long-term outcome of recurrent hepatitis C virus infection following liver transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2013;15:405-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Avolio AW, Cillo U, Salizzoni M, De Carlis L, Colledan M, Gerunda GE, Mazzaferro V, Tisone G, Romagnoli R, Caccamo L, Rossi M, Vitale A, Cucchetti A, Lupo L, Gruttadauria S, Nicolotti N, Burra P, Gasbarrini A, Agnes S; Donor-to-Recipient Italian Liver Transplant (D2R-ILTx) Study Group. Balancing donor and recipient risk factors in liver transplantation: the value of D-MELD with particular reference to HCV recipients. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2724-2736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Halldorson JB, Bakthavatsalam R, Fix O, Reyes JD, Perkins JD. D-MELD, a simple predictor of post liver transplant mortality for optimization of donor/recipient matching. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:318-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Chedid MF, Rosen CB, Nyberg SL, Heimbach JK. Excellent long-term patient and graft survival are possible with appropriate use of livers from deceased septuagenarian and octogenarian donors. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16:852-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Selzner M, Kashfi A, Selzner N, McCluskey S, Greig PD, Cattral MS, Levy GA, Lilly L, Renner EL, Therapondos G. Recipient age affects long-term outcome and hepatitis C recurrence in old donor livers following transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:1288-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Jiménez-Romero C, Caso Maestro O, Cambra Molero F, Justo Alonso I, Alegre Torrado C, Manrique Municio A, Calvo Pulido J, Loinaz Segurola C, Moreno González E. Using old liver grafts for liver transplantation: where are the limits? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10691-10702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |