Published online Dec 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i48.8651

Peer-review started: August 30, 2017

First decision: September 13, 2017

Revised: September 14, 2017

Accepted: October 17, 2017

Article in press: October 17, 2017

Published online: December 28, 2017

Processing time: 119 Days and 21.1 Hours

To examine the evidence about psychiatric morbidity after inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)-related surgery.

PRISMA guidelines were followed and a protocol was published at PROSPERO (CRD42016037600). Inclusion criteria were studies describing patients with inflammatory bowel disease undergoing surgery and their risk of developing psychiatric disorder.

Twelve studies (including 4340 patients) were eligible. All studies were non-randomized and most had high risk of bias. Patients operated for inflammatory bowel disease had an increased risk of developing depression, compared with surgical patients with diverticulitis or inguinal hernia, but not cancer. In addition, patients with Crohn’s disease had higher risk of depression after surgery compared with non-surgical patients. Patients with ulcerative colitis had higher risk of anxiety after surgery compared with surgical colorectal cancer patients. Charlson comorbidity score more than three and female gender were independent predictors for depression and anxiety following surgery.

The review cannot give any clear answer to the risks of psychiatric morbidity after surgery for IBD studies with the lowest risk of bias indicated an increased risk of depression among surgical patients with Crohn’s disease and increased risk of anxiety among patients with ulcerative colitis.

Core tip: Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have higher risk of depression after surgery compared with patients operated for diverticulitis or inguinal hernia but not cancer. Patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) might have higher risk of anxiety after surgery compared with patients with colorectal cancer. Compared with nonsurgical patients, patients operated for UC have higher risk of anxiety and patients operated for Crohn’s disease have higher risk of depression. Among patients with IBD, female gender and Charlson comorbidity score > 3 are risk factors for both anxiety and depression following surgery.

- Citation: Zangenberg MS, El-Hussuna A. Psychiatric morbidity after surgery for inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(48): 8651-8659

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i48/8651.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i48.8651

Compared with other chronic disease populations, patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are younger at the time of diagnosis but they have normal length of lifespan[1]. Hence, they live many years with a chronic disease. Despite the use of immunomodulators, which have reduced the need of surgery, 12% of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) and 6% with ulcerative colitis (UC) still undergo IBD-related surgery within one year of diagnosis[1]. Many of these patients end up with a permanent or temporary stoma.

Previous research has shown a high incidence of psychiatric disorders among patients with IBD, especially those with active disease[2-4]. The burden of psychiatric disorders is enormous[5]. This includes both the personal burden and the cost for the society. Comorbid mental disorders in other chronic diseases are the main reason for functional impairment[6]. This is also likely to be true in IBD. Therefore, preventing development of mental disorders in these patients is imperative.

Already in 1986, the medical society showed interest in the psychological effects of stoma creation among patients with IBD, cancer, and diverticulitis[7]. Recently, in 2014, a narrative review assessed the psychological impact of surgery on patients with IBD[8]. The study found improvement in quality of life, but also an increased risk of depression and anxiety compared with the general population. This seemed contradictory. There are still controversies regarding psychiatric comorbidity in IBD compared to other chronic medical illnesses[9,10].

The objective of this review was to examine the evidence about psychiatric morbidity after IBD-related surgery compared to non-IBD surgery. This systematic review assessed the following study questions, which has not been described in previous publications: (1) do patients with IBD have higher risk of psychiatric disorder after surgery compared with other surgical patients? (2) do patients with IBD have higher risk of psychiatric disorder after surgery compared with non-surgical patients with IBD? and (3) among surgical patients with IBD, how do we identify patients needing extra attention to prevent development of psychiatric disorder?

This systematic review followed PRISMA guidelines[11]. To reduce risk of bias, a study protocol was made at an early stage and stated precise eligibility criteria. The protocol was registered in PROSPERO[12] (registration number CRD42016037600).

Inclusion criteria: (1) studies about patients with IBD (CD and/or UC) undergoing IBD-related surgeries; (2) studies assessing outcomes of psychiatric comorbidity in terms of: ICD (International Classification of Diseases) or DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders); change in psychiatric rating scales indicating psychiatric morbidity [Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)], Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS), State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck depression inventory, or Rorschach content interpretation for anxiety). Those psychiatric rating scales were chosen because they indicate presence of anxiety and/or depression. Yet, they are not alone diagnostic; and (3) clinical trials, retrospective- and prospective cohort studies, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, and case-control studies with no language restrictions.

Exclusion criteria: (1) studies describing psychiatric disorders prior to surgical intervention; (2) studies with delirium diagnosis as outcome; (3) studies exclusively reporting quality of life or single psychological symptoms as part of larger questionnaires not assessing psychiatric morbidity; and (4) case-series, case reports, commentaries, letters, conference abstracts, narrative reviews, and editorials.

The search was performed in the following databases: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library. A search strategy was developed combining MeSH terms (Major Subject Headings) and free-text terms. The search from MEDLINE is reported in the supplementary figure. The search from the three other databases contained the same keywords. The last search in all databases was performed on May 1, 2016. Reference lists from all included articles were screened for relevant studies.

The selection of studies was performed using “Covidence” management tool[13]. Two independent reviewers, blinded to the other reviewer’s decision, completed the selection of studies in two steps. First, title-abstract was screened and afterwards full-text screening of included abstracts was performed. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Zangenberg MS performed the data collection on: authors, publication year, study design, details of populations (CD, UC or mixed IBD), intervention details (type of surgery), risk factor for psychiatric disorder after surgery, outcome measures (ICD, DSM, rating scale), any comparisons used, and results. In articles with mixed participants, data of the IBD population was extracted and reported. One author was contacted to clarify results of study tables[3]. The author of two studies[14,15] was contacted to make sure the patients were not duplicates.

The methods for assessing risk of bias are described in “supplementary methods”. The risk of bias assessment was carried out by Zangenberg MS.

No meta-analysis was conducted due to heterogeneity in methodology and outcome reporting in the included studies. We chose to report our results in three sections according to outcome.

RESULTS

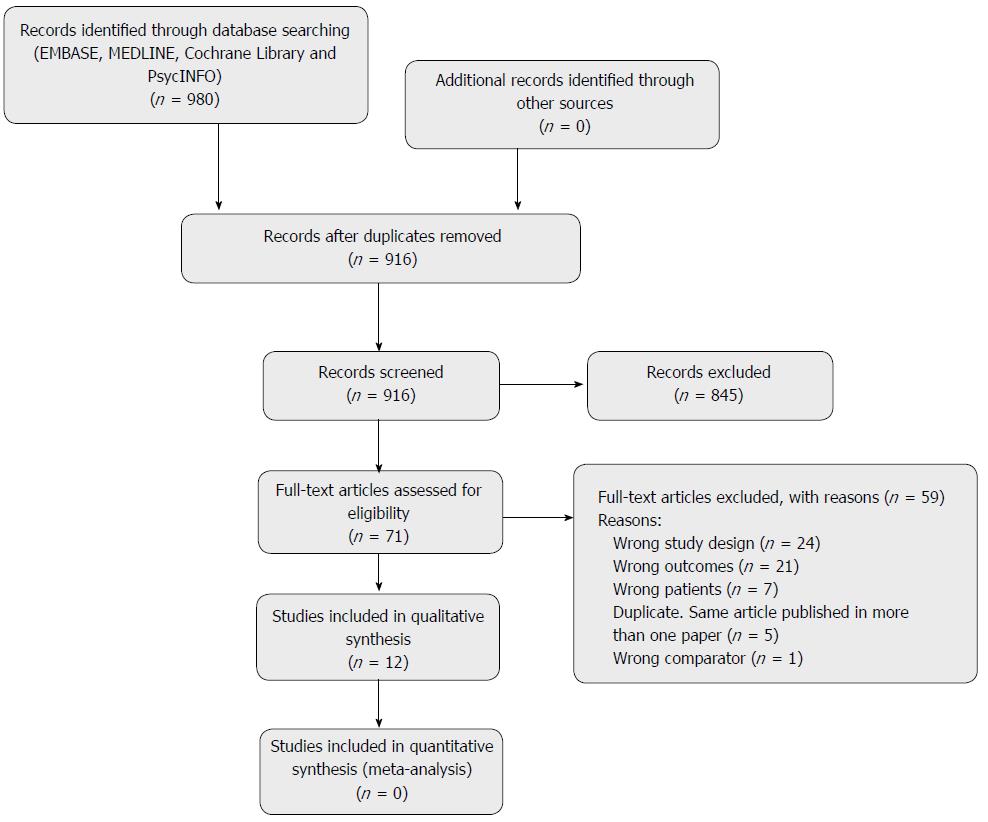

A total of 980 studies were identified using the above-mentioned search strategy. Seventy-one studies were chosen for the full-text screening, from which 12 studies were included in the synthesis of results (Figure 1 shows PRISMA flowchart). No additional studies were found screening the reference list of the included articles. All selected studies for inclusion were in English. Translation was therefore not needed. The 12 included studies covered a total of 4340 patients (n = 2047 patients with UC and n = 2293 patients with CD). All studies found were non-randomized. Characteristics of included studies can be found in Table 1.

| Ref. | Year | Country | Study design | Population | Surgery | Outcome measures | Comparisons |

| Makkar et al[22] | 2015 | Canada | Cross sectional study | 137 patients with UC > 18 yr who were > 1 yr from the final stage of their total IPAA surgery. | IPAA | DASS-21 including subscales for stress, anxiety and depression | Subgroup analysis comparing normal pouch, irritable pouch syndrome and pouch inflammation. All groups had IPAA |

| Panara et al[4] | 2014 | United States | Retrospective cohort study | 393 patients > 18 yr with UC (121) or CD (272) | History of surgical stoma or seton placement as risk factor (from surgical records) | ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification) codes for depression | None |

| Ananthakrishnan et al[16] | 2013 | United States | Retrospective cohort study | 707 with CD and 530 with UC | Bowel resection surgery (ICD records) | ICD-9 codes for depressive disorders or generalized anxiety given after 30days after surgery. | IBD patients not having surgery and patients undergoing surgery for other diseases |

| Analyses of independent predictors of depression and anxiety following IBD-surgery | |||||||

| Knowles et al[14] | 2013 | Australia | Cross sectional study | 83 mixed IBD. (62.7% UC) Age between 18-40 yr | Stoma surgery (self-reported) | HADS (normal = 0-7, mild severity = 8-10, moderate severity = 11-15, severe severity = 16-21) | none |

| Knowles et al[15] | 2013 | Australia | Cross sectional study | 31 with CD | ostomy | HADS | none |

| (normal = 0-7, mild severity = 8-10, moderate severity = 11-15, severe severity = 16-21) | |||||||

| Nahon et al[3] | 2012 | France | Cross sectional study | 1663 with IBD (63.9% CD and 37.1% UC or indeterminate colitis | Past history of surgery as risk factor | HADS > 11 on either subscale was considered “significant” cases of psychological comorbidity | none |

| Schmidt et al[21] | 2007 | Germany | Cross sectional study | 43 with UC | IPAA | HADS ≥ 11 on either subscale (depression/anxiety) indicative of a probable mental disorder | IPAA patients in remission, with pouchitis and with irritable pouch syndrome |

| Häuser et al[20] | 2005 | Germany | Cross sectional study | 101 with UC | IPAA | HADS ≥ 11 on either subscale was considered “significant” cases of psychological comorbidity | UC patients with IPAA vs general german population and UC patients with IPAA vs UC patients without IPAA. |

| Use of psychopharmacological agents | |||||||

| de Oca et al[23] | 2003 | Spain | Cross sectional study | 100 with UC and 12 with CD (discovered postoperative) | IPAA | STAI for Anxiety | Only subgroup (CD vs UC) comparisons |

| Nordin et al[19] | 2002 | Sweden | Cross sectional study | 331 with UC and 161 with CD (all in the range of 18-70 yr of age) | Ileostomy, ileoanal anastomosis and ileorectal anastomosis | HADS where ≤ 7 = “non-case”; 8-10 = “doubtful case”; ≥ 11 = “case” | none |

| Tillinger et al[18] | 1999 | Austria | Prospective cohort study | 16 with CD | Elective ileum or colon resection | Beck depression inventory within one week before operation, three, six and 24 mo postoperative | none |

| Keltikangas-Järvinen et al[17] | 1983 | Finland | Cross sectional study | 32 with UC operated with ileostomy | Operation with ileostomy (follow up = 7 ± 1.2 yr. after the operation) | Beck’s depression scale and Rorschach content interpretation for anxiety | 34 colorectal cancer patients having colostomy |

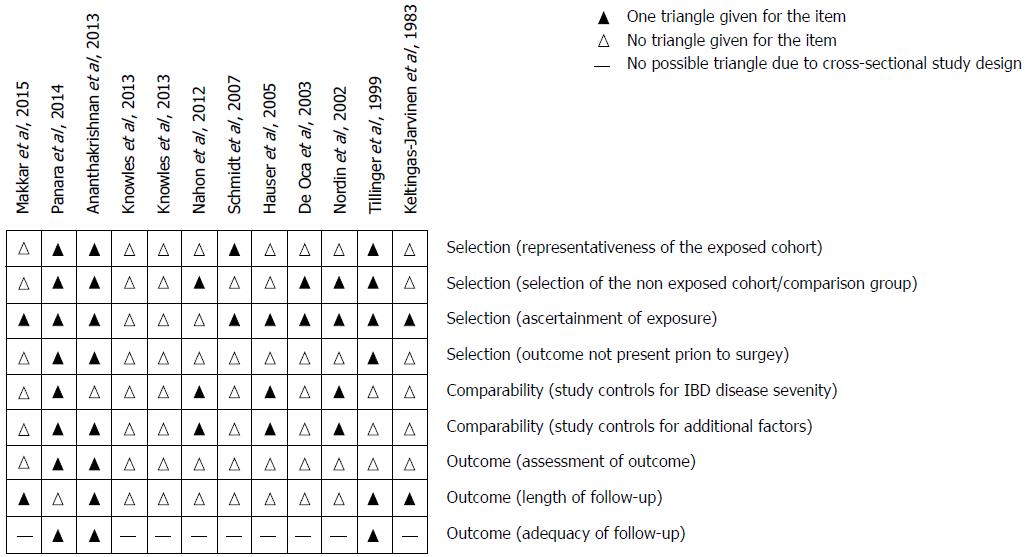

Quality assessment was done using a modified Newcastle-Ottawa scale described in “supplementary methods”. Most studies had high risk of bias. See Figure 2 for a total result of the quality assessment.

The included studies used four different psychiatric rating scales to assess psychiatric morbidity. The scales are mentioned in the methods. The most commonly used scale was HADS which consists of seven items for depression and seven items for anxiety. Each item covers a score from 0-3, where 3 indicates greatest severity. The range of each subscale is 0-21 and the score can be divided in different categories. Most studies use the categories normal/non-cases (0-7), mild/doubtful cases (8-10), moderate (11-15), and severe (16-21). Some mix the last two categories and call is cases/probable mental disorders (11-21).

Eleven studies described depression after IBD-related surgery (Table 2). Two studies found insignificant associations between past history of surgery and depression[3,4]. One study showed that patients operated for IBD had a greater five-year post-operative risk of depression compared with patients operated for diverticulitis or inguinal hernia[16]. The same study looked at CD treated surgically compared with non-surgical CD cases and found a significant increased risk of depression (Table 2). In patients with UC treated with surgery versus non-surgical cases there was no increased risk. These results indicate that patients with CD may be more prone to depression after surgery compared with patients with UC.

| Ref. | Depression results | Anxiety results |

| Nahon et al[3], 2012 | Multivariate analysis of predictive factors found no association between past history of surgery and depression (OR = 0.93, 95%CI: 0.50-1.72) | Multivariate analysis of predictive factors found past history of surgery to be significantly associated with decreased risk of anxiety (OR = 0.47, 95%CI: 0.31-0.71) |

| Panara et al[4], 2014 | Multivariate analysis: history of surgery had a non-significant HR = 1.3 (95%CI: 0.92-1.76; P = 0.13). | - |

| Ananthakrishnan et al[16], 2013 | Chi-square test: Higher 5 yr postoperative risk in IBD group (16%) compared with diverticulitis (9%) and inguinal hernia group (7%) (P < 0.05). Higher risk in CD surgery group compared with non-surgical group (OR = 1.34, 95%CI: 1.01-1.77). No significant increased risk in UC surgery group compared with non-surgical group (OR = 1.21, 95%CI: 0.93-1.58). | no significant increased OR in CD-surgery group compared with non-surgical group (OR = 1.20, 95%CI: 0.93-1.55) or UC-surgery group compared with non-surgical group (OR = 1.26, 95%CI: 0.96-1.65). |

| Keltingas-Jarvinen et al[17], 1983 | Comparisons of means in Beck depression inventory – type of analysis not stated: UC < colorectal cancer | Comparisons of means in Rorschach content interpretation for anxiety – type of analysis not stated: UC > colorectal cancer |

| Tillinger et al[18], 1999 | Wilcoxon test: significantly improved score three and six months postoperatively (P = 0.0038 and 0.0013 respectively). 24 mo postoperatively only improved scores for patients still in remission. | - |

| Nordin et al[19], 2002 | Percentage of population divided on HADS depression subscales: 87% “non-cases”; 9% “doubtful cases”; 4% cases | Percentage of population divided on HADS anxiety subscale: 71% “non-cases”; 14% “doubtful cases”; 15% cases. |

| Subgroup analysis of depression: unpaired t-test showed no difference between CD and UC patients with ileostomies and those without ileostomies. | Subgroup analysis of anxiety: unpaired t-test showed no difference between CD and UC patients with ileostomies and those without ileostomies. | |

| Knowles et al[14], 2013 | Percentage of population divided on HADS depression subscales: 84% normal; 6% mild; 10% moderate; 0% severe | Percentage of population divided on HADS anxiety subscale: 50% normal; 24% mild; 16% moderate; 10% severe. |

| Knowles et al[15], 2013 | Percentage of population divided on HADS depression subscales: 58% normal; 26% mild; 16% moderate-severe | Percentage of population divided on HADS anxiety subscale: 51% normal; 39% mild; 10% moderate-severe |

| Häuser et al[20], 2005 | Student’s t-test: no increased probable (HADS ≥ 11) mental disorder in UC with IPAA vs the general German population. Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test: no difference in HADS depression subscales between UC patients with IPAA† compared to UC without IPAA. | Student’s t-test: no increased probable (HADS ≥ 11) mental disorder in UC with IPAA vs the general German population. Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test: no difference on HADS anxiety subscale between UC patients with IPAA compared to UC without IPAA. |

| Schmidt et al[21], 2007 | Kruskal-Wallis test showed no significant difference in HADS depression subscales between IPAA subgroups | Kruskal-Wallis test showed no significant difference on HADS anxiety subscale between IPAA† subgroups |

| Makkar et al[22], 2015 | ANOVA: Significant difference between DASS among patients with irritable pouch syndrome (11.7 ± 9.7), pouch inflammation (8.1 ± 9.1) and normal pouch (4.4 ± 6.2), P =0.012. | ANOVA: no significant difference between DASS among patients with irritable pouch syndrome (8.1 ± 7.0), pouch inflammation (6.0 ± 6.8), and normal pouch (4.2 ± 4.9), P = 0.1 |

| de Oca et al[23], 2003 | - | Student’s t-test: CD < UC on anxiety values of the STAI ( P = 0.014) |

Patients with colorectal cancer and a colostomy scored higher on Beck depression inventory than patients with UC and an ileostomy[17]. In another study, Beck depression inventory was used preoperative, 3, 6, and 24 mo after elective bowel resection for CD. Depression scores at three and six month follow-up declined compared with the preoperative score[18]. After 24 mo, improvement was only seen in the group still in remission. The results suggest decreased risk of depression, but did not control for disease activity, which can be an important confounder.

Three studies measured depression after surgery (HADS-score ≥ 11) and found a prevalence of 4%-16%[14,15,19]. The highest prevalence (16%) was found in the cohort consisting of only patients with Crohn’s disease, which could indicate that patients with CD are more prone to depression after stoma surgery compared with mixed cohorts including patients with UC. None of the studies measuring HADS compared the scores with non-surgical patients or other surgical patients.

Three studies investigated ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) as an intervention[20-22]. A study of patients with UC having IPAA found no difference in HADS between groups with IPAA and patients without[20]. Two studies looking at subgroups of IPAA cohorts found increased depression scores in patients with irritable pouch syndrome[21,22]. This indicates that only patients with problems (e.g., irritable pouch syndrome) after IPAA has increased risk of depression.

Collectively, most studies using statistical comparisons found no increased risk of depression following surgery for IBD, although some studies indicate that patients with CD undergoing surgery are more prone to depression compared with patients medically treated for CD.

Ten studies described anxiety outcome following IBD-related surgery (Table 2). In one study, it was shown that IBD-related surgery was not significantly associated with development of anxiety[16]. Another study found a quite strong association between history of surgery and a decrease of anxiety (OR = 0.47, 95%CI: 0.31-0.71, P < 0.0001)[3].

Three studies used HADS (defined by cases scoring ≥ 11) to describe anxiety prevalence after IBD-related surgery and found 10%-26%[14,15,19]. The highest prevalence was found in a mixed IBD cohort having stoma surgery. The remarkably lower incident in the CD stoma cohort could indicate that anxiety problems are greater among patients with UC. Yet, the studies are heterogeneous and precautions need to be paid before giving any conclusions.

One study compared colorectal cancer patients with colostomies and patients with UC and ileostomy[17]. The patients with UC scored highest on Rorschach content interpretation for anxiety.

Four studies investigated development of anxiety following IPAA[20-23]. Three studies found no difference in anxiety scores between IPAA and non-IPAA treated patients or subgroups of IPAA treated patients[20-22]. A study with 100 patients with UC and 12 patients with CD showed significantly lower levels of anxiety in the group with CD[23]. Unfortunately, it was not stated if the STAI score for the UC group was high enough to indicate possible anxiety disorder.

Taken together, the only study comparing with other surgical patients found that patients with UC had higher risk of anxiety after surgery compared with colorectal patients. There was no difference in anxiety prevalence between patients with UC having IPAA and non-surgical patients with UC. Also, patients with UC seems to be more prone to anxiety than patients with CD.

Independent predictors of depression in patients with CD were identified using multivariate analyses[16]. The independent predictors were: Charlson comorbidity score three or more (OR = 4.3, 95%CI: 2.82-6.57), stoma surgery (OR = 1.90, 95%CI: 1.15-3.13), female gender (OR = 1.77, 95%CI: 1.16-2.71), perianal disease (OR = 1.64, 95%CI: 1.01-2.69), immunomodulatory use (OR = 1.56, 95%CI: 1.03-2.38), and surgery within three years (OR = 1.54, 95%CI: 1.01-2.37). For patients with UC only Charlson score three or more (OR = 3.73, 95%CI = 2.33-5.97) and female gender (OR = 2.92, 95%CI: 1.80-4.76) were identified as risk factors for depression[16].

The same multivariate analysis was performed for development of anxiety in the same two populations. In patients with CD, the following factors were identified: surgery within three years (OR = 2.19, 95%CI: 1.44-3.33), female gender (OR = 2.07, 95%CI: 1.35-3.19), Charlson comorbidity score three or more (OR = 1.84, 95%CI: 1.19-2.84), two surgeries (OR = 1.79, 95%CI: 1.09-2.93), and stoma surgery (OR = 1.73, 95%CI: 1.05-2.85). Again, for patients with UC, only Charlson score (OR = 3.26, 95%CI: 1.98-5.38) and female gender (OR = 1.84, 95%CI: 1.18-2.87) was identified as independent risk factors[16]. The multivariate analysis showed no significant correlation between age at surgery and depression or anxiety after surgery in IBD patients.

It seems that patients with IPAA who develop irritable pouch syndrome have higher risk of depressive symptoms but not anxiety symptoms[22].

We found evidence that patients with IBD have higher post-operative risk of depression compared with patients operated for diverticulitis and inguinal hernia[16]. Yet, looking at patients with UC separately, they scored lower on Beck depression inventory after stoma surgery compared with colorectal cancer patients, which might be related to the fact that surgery is curative for UC[17]. In terms of anxiety, patients with UC and an ileostomy scored higher on Rorschach content interpretation compared with patients with colorectal cancer and a colostomy[17]. In the comparison of patients with IBD with other disease populations, there is a risk that the results simply reflect the difference between the disease groups and not the effect of surgery on the different diseases. This is likely sine earlier studies have shown a higher risk in patients with IBD in general compared with other diseases[2].

Comparing patients with IBD undergoing surgery with non-surgical IBD cases we only found studies assessing specifically CD or UC. Some studies indicate that patients with CD have higher risk of depression while UC might have higher risk of anxiety. The multiple surgical interventions in CD vs curative nature of surgery in UC might be an explanation, while worries about permanent stoma may lead to anxiety in UC. Also, we know very little about identifying patients needing extra attention to reduce the incidence of psychiatric comorbidity after surgery for IBD. One study showed that predictors of both anxiety and depression in patients after IBD-related surgery are female gender and comorbidity. This is not surprising, since more women than men suffer from depression and anxiety in general[24,25]. Also, comorbidity and disability is associated with anxiety and depression in the general population[25]. Age at surgery was not an independent risk factor, emphasizing that the awareness on psychological impact of surgery is important in all age groups.

There is strong evidence that increased incidence of psychiatric disorders among patients with IBD is strongly correlated to disease activity[2]. Few of the included studies adjusted for this possible confounding factor.

The limitations of this review were mainly related to the non-randomized study designs and the heterogeneity of the included studies. Differences in methodology and outcome reporting makes the generalization to the broad surgical IBD population very difficult and interpretation of the results need to be precautious.

The bulk of the included studies were cross-sectional studies and different types of bias can be suspected. The risk that different patients have different likeability to answer questionnaires raised concerns regarding nonresponse bias. It can be hypothesized that patients with greater psychological difficulties will be less likely to return questionnaires due to lack of psychological capacity to do so. This could underestimate the incidence of psychiatric comorbidity. On the other hand, patients with psychiatric problems could be more motivated to return questionnaires assessing this matter. If this was the case, the incidence in the included observational studies could be overestimated. In observational studies with questionnaires there is a risk of recall bias. It could be, that patients who already have an outcome, in this case psychiatric disorders, would report differently about the risk factors they have had in the past. Also, there is a risk of detection bias due to different rating scales and outcome parameters. For risk of bias across studies, the proportion of information from studies of high risk of bias is sufficient to affect the interpretation of the results. A big problem with cross-sectional studies is the question of causality. Because the risk factors and the outcomes are assessed at the same point in time, it is difficult to know if the risk factors actually preceded the outcomes. In cross sectional studies using questionnaires, no outcome could be assessed prior to the intervention to make sure that any psychiatric morbidity wasn’t present prior to surgery.

Many of the included studies lacked a control group, which made it difficult to answer our study questions. We need analyses of both CD and UC within the same population using the same scores and comparing with other diseases treated surgically, plus non-surgical IBD cases. Measuring e.g, HADS before and after surgical intervention in a prospective manner would create representative results.

In conclusion, the review cannot give any clear answer to the risks of psychiatric morbidity after surgery for IBD. Studies with the lowest risk of bias show increased risk of depression among surgical patients with CD and increased risk of anxiety for patients with UC. Among patients planning to undergo IBD-related surgery, females and those with comorbidities need extra attention to prevent the development of psychiatric disorders.

Previous research has shown a high incidence of psychiatric disorders among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), especially those with active disease this may lead to personal burden and prohibitive costs for the society.

In patients with IBD might have a higher risk for postoperative psychiatric disorders compared with other patients undergoing same type of surgery. This risk may simply reflect the difference between the disease groups and not the effect of surgery on the different diseases.

The aim of this review was to examine the evidence about psychiatric morbidity after IBD-related surgery.

This is a systemic review which adheres to PRISMA guidelines. Research question and protocol were published at PROSPERO (CRD42016037600). Inclusion criteria were studies describing patients with inflammatory bowel disease undergoing surgery and their risk of developing psychiatric disorder. Studies describing psychiatric disorders prior to surgical intervention and studies exclusively reporting quality of life or single psychological symptoms as part of larger questionnaires not assessing psychiatric morbidity were excluded.

Patients with IBD have higher risk of depression after surgery compared with patients operated for diverticulitis or inguinal hernia but not cancer. Patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) might have higher risk of anxiety after surgery compared with patients with colorectal cancer. Compared with nonsurgical patients, patients operated for UC have higher risk of anxiety and patients operated for Crohn’s disease have higher risk of depression. Among patients with IBD, female gender and Charlson comorbidity score > 3 are risk factors for both anxiety and depression following surgery.

Patients with IBD have higher postoperative risk for anxiety and/or depression.

Large multi-center prospective studies are warranted to show and quantify the risk of postoperative psychiatric disorders in patients with IBD.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Denmark

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Horesh N, Triantafillidis JKK, Trifan A S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Vind I, Riis L, Jess T, Knudsen E, Pedersen N, Elkjaer M, Bak Andersen I, Wewer V, Nørregaard P, Moesgaard F. Increasing incidences of inflammatory bowel disease and decreasing surgery rates in Copenhagen City and County, 2003-2005: a population-based study from the Danish Crohn colitis database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1274-1282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 379] [Cited by in RCA: 389] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Häuser W, Janke KH, Klump B, Hinz A. Anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: comparisons with chronic liver disease patients and the general population. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:621-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nahon S, Lahmek P, Durance C, Olympie A, Lesgourgues B, Colombel JF, Gendre JP. Risk factors of anxiety and depression in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2086-2091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Panara AJ, Yarur AJ, Rieders B, Proksell S, Deshpande AR, Abreu MT, Sussman DA. The incidence and risk factors for developing depression after being diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease: a cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:802-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Flachs EM, Eriksen L, Koch MB, Ryd JT, Dibba E, Skov-Ettrup L, Juel K. Statens Institut for Folkesundhed, Syddansk Universitet. Sygdomsbyrden i Danmark. København. Sundhedsstyrelsen;. 2015; Available from: https://www.sst.dk/da/sygdom-og-behandling/~/media/00C6825B11BD46F9B064536C6E7DFBA0.ashx. |

| 6. | Kessler RC, Ormel J, Demler O, Stang PE. Comorbid mental disorders account for the role impairment of commonly occurring chronic physical disorders: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45:1257-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Thomas C, Madden F, Jehu D. Psychological effects of stomas--I. Psychosocial morbidity one year after surgery. J Psychosom Res. 1987;31:311-316. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Spinelli A, Carvello M, D’Hoore A, Pagnini F. Psychological perspectives of inflammatory bowel disease patients undergoing surgery: rightful concerns and preconceptions. Curr Drug Targets. 2014;15:1074-1078. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Graff LA, Walker JR, Bernstein CN. Depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease: a review of comorbidity and management. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1105-1118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 410] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mikocka-Walus A, Knowles SR, Keefer L, Graff L. Controversies Revisited: A Systematic Review of the Comorbidity of Depression and Anxiety with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:752-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 448] [Cited by in RCA: 407] [Article Influence: 45.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6253] [Cited by in RCA: 7636] [Article Influence: 477.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | National Institute for Health Research. PROSPERO 2016 [cited 2016-6-3]. Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/. |

| 13. | Covidence. Covidence management tool 2016 [cited 2016-6-7]. Available from: https://www.covidence.org/. |

| 14. | Knowles SR, Cook SI, Tribbick D. Relationship between health status, illness perceptions, coping strategies and psychological morbidity: a preliminary study with IBD stoma patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e471-e478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Knowles SR, Wilson J, Wilkinson A, Connell W, Salzberg M, Castle D, Desmond P, Kamm MA. Psychological well-being and quality of life in Crohn’s disease patients with an ostomy: a preliminary investigation. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2013;40:623-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ananthakrishnan AN, Gainer VS, Cai T, Perez RG, Cheng SC, Savova G, Chen P, Szolovits P, Xia Z, De Jager PL. Similar risk of depression and anxiety following surgery or hospitalization for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:594-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Keltikangas-Järvinen L, Loven EL. Stability of personality dimensions related to cancer and colitis ulcerosa: preliminary report. Psychol Rep. 1983;52:961-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tillinger W, Mittermaier C, Lochs H, Moser G. Health-related quality of life in patients with Crohn’s disease: influence of surgical operation--a prospective trial. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:932-938. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Nordin K, Påhlman L, Larsson K, Sundberg-Hjelm M, Lööf L. Health-related quality of life and psychological distress in a population-based sample of Swedish patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:450-457. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Häuser W, Janke KH, Stallmach A. Mental disorder and psychologic distress in patients with ulcerative colitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:952-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Schmidt C, Häuser W, Giese T, Stallmach A. Irritable pouch syndrome is associated with depressiveness and can be differentiated from pouchitis by quantification of mucosal levels of proinflammatory gene transcripts. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1502-1508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Makkar R, Graff LA, Bharadwaj S, Lopez R, Shen B. Psychological Factors in Irritable Pouch Syndrome and Other Pouch Disorders. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2815-2824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | de Oca J, Sánchez-Santos R, Ragué JM, Biondo S, Parés D, Osorio A, del Rio C, Jaurrieta E. Long-term results of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2003;9:171-175. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Olsen LR, Mortensen EL, Bech P. Prevalence of major depression and stress indicators in the Danish general population. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109:96-103. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Alonso J, Lépine JP; ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 Scientific Committee. Overview of key data from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD). J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68 Suppl 2:3-9. [PubMed] |