Published online Dec 7, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i45.8082

Peer-review started: June 1, 2017

First decision: June 23, 2017

Revised: July 7, 2017

Accepted: August 9, 2017

Article in press: October 24, 2017

Published online: December 7, 2017

Processing time: 42 Days and 0.1 Hours

To investigate the effect of disease activity or thiopurine use on low birth weight and small for gestational age in women with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

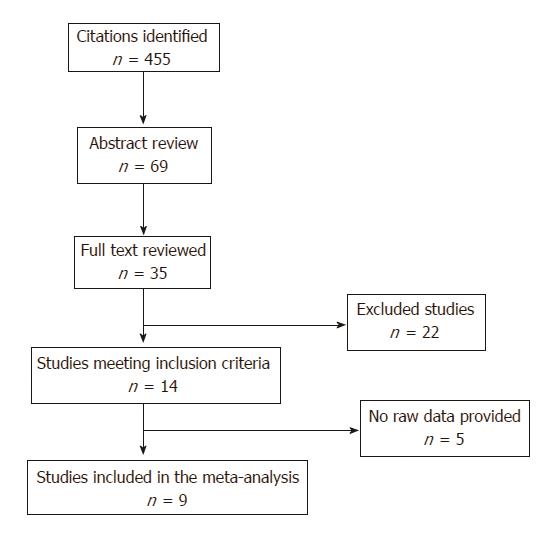

Selection criteria included all relevant articles on the effect of disease activity or thiopurine use on the risk of low birth weight (LBW) or small for gestational age (SGA) among pregnant women with IBD. Sixty-nine abstracts were identified, 35 papers were full text reviewed and, only 14 of them met inclusion criteria. Raw data were extracted to generate the relative risk of LBW or SGA. Quality was assessed using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale.

This meta-analysis is reported according to PRISMA guidelines. Fourteen studies met inclusion criteria, and nine reported raw data suitable for meta-analysis. We found an increased risk ratio of both SGA and LBW in women with active IBD, when compared with women in remission: 1.3 for SGA (4 studies, 95%CI: 1.0-1.6, P = 0.04) and 2.0 for LBW (4 studies, 95%CI: 1.5-2.7, P < 0.0001). Women on thiopurines during pregnancy had a higher risk of LBW (RR 1.4, 95%CI: 1.1-1.9, P = 0.007) compared with non-treated women, but when adjusted for disease activity there was no significant effect on LBW (RR 1.2, 95%CI: 0.6-2.2, P = 0.6). No differences were observed regarding SGA (2 studies; RR 0.9, 95%CI: 0.7-1.2, P = 0.5).

Women with active IBD during pregnancy have a higher risk of LBW and SGA in their neonates. This should be considered in treatment decisions during pregnancy.

Core tip: There are conflicting data on the impact of disease activity and thiopurine use on birth weight in pregnant women with inflammatory bowel disease. The individual impact of these factors in low birth weight (LBW) and small gestational age (SGA) has not been systematically evaluated to date. For these reasons, we performed a meta-analysis to identify the effect of disease activity or thiopurine use on the rates of LBW and SGA in these patients. Since many women become non-adherent to medications during pregnancy, for fear of a negative effect on the fetus, further information would be useful in counseling women.

- Citation: Gonzalez-Suarez B, Sengupta S, Moss AC. Impact of inflammatory bowel disease activity and thiopurine therapy on birth weight: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(45): 8082-8089

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i45/8082.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i45.8082

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic disease, often affecting young women of reproductive age. The potential impact of IBD on their pregnancy is one of the main concerns of these women. Several retrospective case-control studies have reported an increase of preterm delivery, low birth weight (LBW), small for gestational age (SGA) or congenital abnormalities (CAs) in patients with IBD, when compared to healthy controls[1-4] .These conclusions have been confounded by the individual roles that disease activity and maintenance medications may play in these birth outcomes. Population-based studies from Europe have concluded that disease activity did not significantly increase the risk of low birth weight in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD), whereas other studies have reported an increase in small for gestational age (SGA) births[5,6]. A large prospective study including 332 pregnancy IBD women, reported that women with IBD had similar pregnancy outcomes women without IBD, but most of the IBD women were in remission or on maintenance therapy[7]. Since many women stop taking therapy during pregnancy, for fear of a negative effect on the fetus, further information on the impact of disease relapse while pregnant would be useful in counseling women[8] . A recent multicenter and prospective study[9], where IBD women were asked to complete a questionnaire about their concerns on pregnancy and medications, demonstrated that a lack of knowledge or inappropriate education and counseling may lead to inappropriate treatment decisions.

A key factor in preventing relapse is use of maintenance medication. Thiopurines (azathioprine/mercaptopurine) have been a mainstay of maintenance therapy in IBD globally since the 1980s. There have been conflicting data on the birth outcomes of women with IBD treated with thiopurines, with population-based studies showing no impact, but referral centers reporting an increased risk of SGA births or pre-terms births[10-12].

Since to women with IBD who are pregnant have a higher risk of adverse events, early consultation with specialists can help them to plan appropriate pregnancy and delivery[13]. Information on the role of disease activity and use of maintenance thiopurines can be critical in these discussions. The individual impact of these factors in LBW and SGA in women with IBD has not been systematically evaluated to date. For these reasons, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to identify the pooled effect of disease activity or thiopurine use on the rates of LBW and SGA in women with IBD.

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted with guidance provided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews[14]. It is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines[15].

We included observational studies in this meta-analysis that met the following inclusion criteria: (1) participants: Studies performed in pregnant women with IBD; (2) interventions: Described any disease activity or thiopurine use as defined by each study’s primary definition of use. We then sub-classified based on duration of exposure; (3) comparators: Pregnant women with IBD not exposed to disease activity or thiopurines; (4) outcomes: Risk Ratio (RR) and 95%CI of development of either LBW (a birth weight < 2500 mg), or SGA (a weight below the 10th percentile for gestational age); and (5) studies: Reported with clear definitions of LBW and SGA. Provide sufficient data to allow estimation of effect size. Inclusion was not otherwise restricted by study size, language, or publication type. When there were multiple publications from the same cohort, data from the most recent comprehensive report were included.

The clinical investigators searched Medline, Embase, ClinicalTrials.gov, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library (up to October 2016), for all relevant articles on the effect of disease activity or thiopurine use on the risk of LBW or SGA among pregnant women with IBD. Medical subject heading (MeSH) or keywords used in the search included the following: “ulcerative colitis”, “Crohn’s disease”, “Crohn’s”, “colitis”, “inflammatory bowel disease”, “IBD”, “activity”, “relapse”, “thiopurine”, “azathioprine”, “mercaptopurine”, “low birth weight”, “LBW”, “small for gestational age”, “SGA”. We manually searched review articles and abstracts (2006-2016) from major gastroenterology conferences (American Gastroenterology Association, American College of Gastroenterology, British Society of Gastroenterology, United European Gastroenterology Week, European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization). Only abstracts summarized in English were used for screening purposes.

Two authors (BGS, SS) independently and without blinding identified and reviewed potentially relevant articles to determine if they fulfill the inclusion criteria. A third author (ACM) adjudicated on whether or not studies should be included, were consensus not reached.

An unblinded review author used specially designed assessment forms to extract the relevant data. The forms captured data, including: author, geographical region, year of publication, study design, nature of disease, outcomes (cancer/ dysplasia), and drug used, dose effect, duration of treatment, setting in which the study was performed, and adjusted and unadjusted OR. Study quality and risk of bias were assessed according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) guidelines. Patient selection methods, comparability of the studies groups and outcome were evaluated (Supplementary Table 1)[16]. Studies are assigned points for different questions in each category and can have a maximum of nine points. We considered higher than seven points as high quality[16].

Our analysis focused on the risk of the development of LBW or SGA among pregnant women with IBD, based on whether or not they had active disease or been treated with thiopurines. The random effects model as proposed by DerSimonian and Laird[17] was used to calculate pooled risk ratio (RR) and 95%CI. The effect estimate used was the RR, as a suitable estimate of relative risk. Potential publication bias was examined by funnel plots. Heterogeneity was examined by the Q statistic and the I2 statistic[18].

The Q and I2 statistics were used to test statistical heterogeneity among studies. For the Q statistic, a P value of less than 0.1 is considered representative of statistically significant heterogeneity. An I2 index of around 25% is considered to demonstrate low levels of heterogeneity, 50% medium, and 75% high. Sensitivity analyses were conducted, omitting each study in turn to screen for outliers with respect to results, study population, study design, or duration of thiopurines exposure. Analyses were performed using the Review Manager (RevMan, Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, the Cochrane Collaboration, 2014).

Study selection and characteristics are shown in Figure 1; of the 69 abstracts identified, 35 papers were full text reviewed and, only 14 of them met inclusion criteria. Twenty-two papers were excluded for different reasons (supplementary Table 2) and 5 papers were not included in the meta-analysis because raw data was not available. Four studies reported data about disease activity in IBD patients and SGA; the same number of papers reported data about the prevalence of LBW. The prevalence of SGA in IBD patients on thiopurines treatment was described in 2 papers and, finally, LBW in newborns on thiopurines treatment and LBW were reported in 5 studies.

Nine studies reported raw data suitable for meta-analysis (Table 1)[5,6,19-25]. All but two of these studies had a retrospective design. Mean length of follow up was 18.7 years, ranging from 3 to 15 years.

The analysis on disease activity was carried out on a total of 1128 IBD pregnancies with active disease vs 1280 IBD pregnancies in remission. There was not a homogeneous definition of “active disease” in the included studies (Table 2). Pregnancies on or off thiopurines treatment (782 vs 3946 patients) were also analyzed. Outcomes evaluated were SGA and LBW. For the thiopurine-exposed groups, the proportions of patients exposed to other medications are shown in supplementary Table 3.

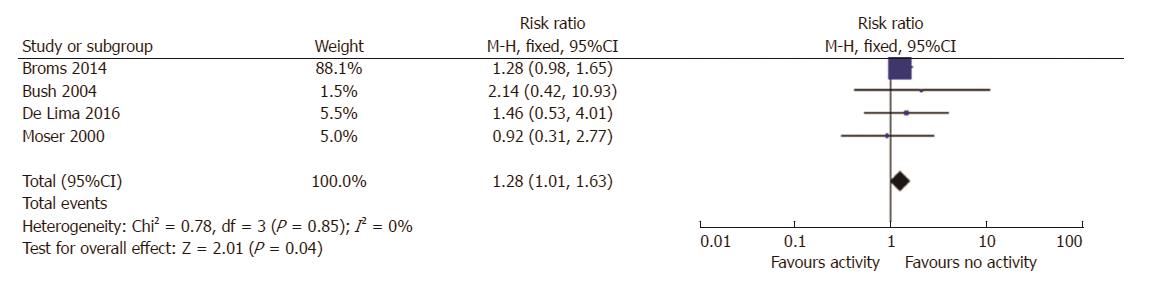

Six studies reported data about disease activity and SGA, 2 prospective study and 4 with retrospective design[6,19-21]. Amongst the 1115 pregnancies in women with active disease, 12% (130/1115) resulted in SGA birth, compared to 9% in women with IBD in remission. The risk ratio for SGA with active disease was 1.3 (95%CI: 1.0-1.6, P = 0.04; Figure 2). There was no statistical heterogeneity amongst these studies (I2 = 0%).

| Study ID | Yr | Study period | Type of study | Sample size | IBD patients with active disease | IBD patients with inactive disease | Outcomes |

| Disease activity and SGA | |||||||

| Bröms et al[19] | 2014 | 2006-2010 | R | 470110 | 988 | 972 | SGA and LBW |

| Bush et al[20] | 2004 | 1986-2001 | R | 56514 | 22 | 94 | SGA and LBW |

| de Lima-Karagiannis et al[21] | 2016 | 2008-2014 | P | 298 | 92 | 134 | SGA and LBW |

| Moser et al[6] | 2000 | 1993-1997 | R | 130 | 13 | 52 | SGA |

| Stephansson et al[27] | 2011 | 1994-2006 | R | 871579 | No raw data provided | SGA | |

| Mahadevan et al[26] | 2012 | P | 797 | No raw data provided | SGA | ||

| Disease activity and LBW | |||||||

| Bortlik et al[24] | 2013 | 2007-2012 | R | 41 | 10 | 31 | LBW |

| Bröms et al[19] | 2014 | 2006-2010 | R | 470110 | 988 | 972 | SGA and LBW |

| Bush et al[20] | 2004 | 1986-2001 | R | 56514 | 22 | 94 | SGA and LBW |

| de Lima-Karagiannis et al[21] | 2016 | 2008-2014 | P | 298 | 92 | 134 | SGA and LBW |

| Molnár et al[28] | 2010 | R | 167 | No raw data provided | LBW | ||

| Bortoli et al[7] | 2011 | 2003-2006 | P | 664 | No raw data provided | LBW | |

| Treatment and SGA | Thiopurine exposure | Non thiopurine exposure | |||||

| Bröms et al[19] | 2014 | 2006-2010 | R | 470110 | 421 | 1539 | SGA and LBW |

| Cleary BJ(23) | 2009 | 1995-2007 | R | 1164030 | 315 | 676 | SGA and LBW |

| Treatment and LBW | |||||||

| Bröms et al[19] (AZA) | 2014 | 2006-2010 | R | 470110 | 421 | 1539 | SGA and LBW |

| Cleary et al[23] | 2009 | 1995-2007 | R | 1164030 | 315 | 1676 | SGA and LBW |

| Komoto et al[25] (AZA) | 2016 | 2008-2014 | R | 72 | 7 | 29 | LBW |

| Nørgård et al[5] | 2007 | 1996-2004 | R | 900 | 20 | 628 | LBW |

| Shim et al[22] | 2011 | 1996-2006 | R | 93 | 19 | 74 | LBW |

| Nørgård et al[10] | 2003 | 1991-2000 | R | 19437 | No raw data provided | LBW |

| Study | Active or inactive disease definition |

| Bröms et al[19] | Any change in the treatment |

| Bush et al[20] | Hospitalization |

| Moser et al[6] | Surgery due to a flare of the disease |

| Shim et al[22] | |

| de Lima-Karagiannis et al[21] | HBI > 5 |

| Komoto et al[25] | SCCAI > 2; Partial Mayo Score Fecal calprotectin > 200 microgr/gr |

| Bortlik et al[24] | Consideration of treating physician |

Two studies did not report raw data, so was excluded from the meta-analysis[26,27]. Stephansson et al[27] reported a higher adjusted prevalence odds ratio of SGA in women with Ulcerative Colitis (UC) compared to controls (Adj POR 1.2) but this risk was higher in women with UC who had been hospitalized for UC (Adj POR 1.4) compared to outpatient women (Adj POR 0.95), suggesting that disease activity influenced this outcome.

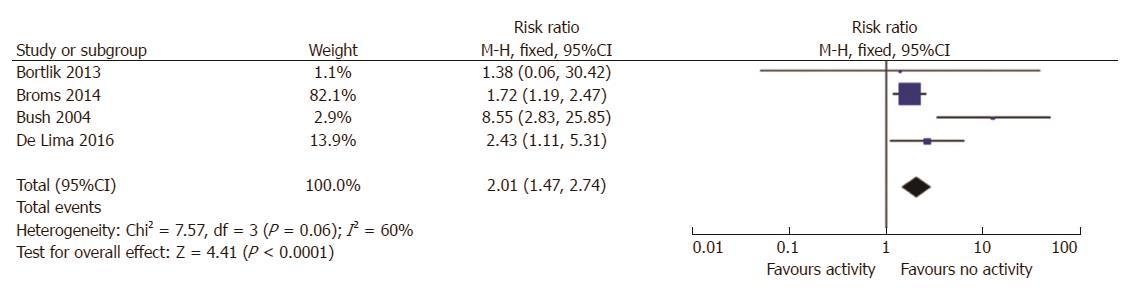

Six studies reported data on LBW rates according to disease activity. Three had a prospective design and 3 were retrospective. Two studies provided no raw data[7,28], thus 4 were included in the meta-analysis[19-21,24]. Women with IBD with active disease had a higher risk ratio of LBW than women with inactive disease (RR = 2; 95%CI: 1.5-2.7, P < 0.0001; Figure 3). There was significant statistical heterogeneity amongst these studies (I2 = 60%), based on the inclusion of one study[20] from a tertiary referral center, where the RR for LBW was 8.6. When this was excluded from the analysis the heterogeneity was 0%, but the RR for LBW remained significantly elevated (RR = 1.8, 95%CI: 1.5-2.7, 1.3-2.15, P = 0.0004).

One study was not included in the meta-analysis as it included no infants with birth weight less than 2500 g. This prospective and multi-centric European case-control study, called ECCO-EpiCom, only reported mean birth weight, which was lower in those with active disease[7]. In only one study[19], patients were grouped by timing of their flare-up (early pregnancy, late pregnancy or both). They reported a 3-4-fold risk increase of low birth weight if the flare event was in both early and late pregnancy.

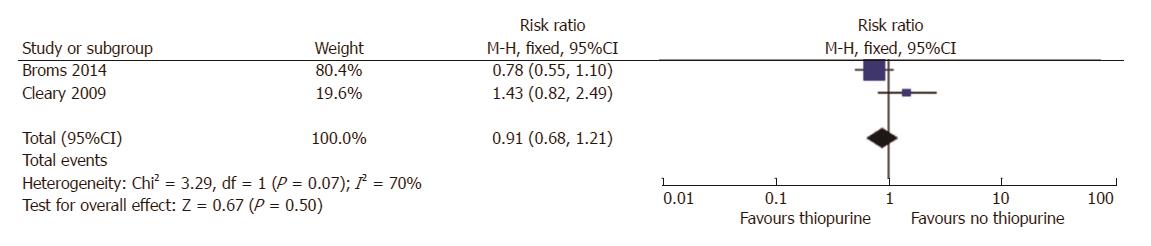

Since thiopurines have been a mainstay maintenance medication in IBD in many studies, and there was conflicting data regarding its impact on birth weight, we next analyzed studies that examined this issue. For the outcome of SGA, only 2 studies reported the SGA rates in patients on thiopurines, compared to non-thiopurine patients[19,23]. No differences were observed between SGA risk in treated or non-treated women with IBD (RR = 0.9, 95%CI: 0.7-1.2, P = 0.50; Figure 4). There was significant statistical heterogeneity amongst these studies (I2 = 70%). This is likely because the paper by Cleary did not control for disease activity[23].

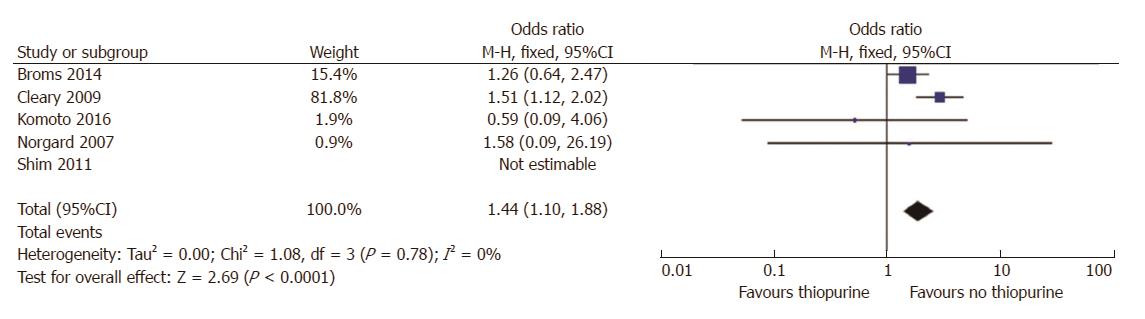

Five studies reported raw data on LBW outcomes in women treated with thiopurines suitable for meta-analysis[3-7], including 782 patients on treatment and 3946 non -treated. There was a higher risk ratio of LBW in women on thiopurines (RR = 1.4, 95%CI: 1.1-1.9, P = 0.007; Figure 5), however, when we only included the study that adjusted for disease activity, there was no significant effect of thiopurines on LBW (RR = 1.2, 95%CI: 0.6 - 2.2; P = 0.6)[19].

One of the most important questions for IBD physicians and patients is what effect disease activity and drug exposure will have on pregnancy outcomes. Previous studies reported an increased risk of LBW in women with IBD, but neither disease activity nor therapies were assessed separately[1-4]. On the other hand, some studies found increased odds of LBW and SGA among infants born to mothers with CD but not those with UC[2].

Active disease during conception or pregnancy was previously associated with fetal loss, LBW and preterm birth[20,29]. Based on this, the 2010 ECCO Consensus recommended that clinicians achieve clinical remission of CD patients before pregnancy[30]. In contrast, Mahadevan et al[31] did not identify any relationship between active disease and adverse birth outcomes in an insured cohort in California.

The present meta-analysis, that included 9 studies, suggests that women with active disease during pregnancy have an increased risk of SGA and LBW in their neonates. This effect estimate averages the risk across different patient populations, and provides an estimate to consider when encouraging women to continue maintenance medications for IBD. This should also factor-in the role of peri-conception disease activity on probability of remission during pregnancy, an issue upon which we have previously reported[32]. Due to lack of reporting of sub-group data, we were unable to undertake sensitivity analysis by disease (UC or CD) or definition of ‘active’ disease. The mechanisms for this risk are unknown, but possible mechanisms include the physiological disruption of inflammation, in parallel with dietary restrictions and steroid use, may increase the risk of LBW or SGA[33-35].

When the relationship between thiopurine exposure was analyzed, most studies did not discriminate between patients with active disease on thiopurines, and those in remission on thiopurines. The study by Bröms et al[19] was most informative on this matter; when risk of LBW was controlled for disease activity, no significant effect of thiopurines was noted. This conclusion is consistent with the population-based studies on this topic, with cohorts predominantly in clinical remission[10].

There are several limitations to this meta-analysis. There is a great deal of heterogeneity regarding the definition of “active disease”, and drug exposure. The criteria for clinical activity included medical record review, pharmacy data and patient contact, all of which have limitations. In addition, the influence of potentially clinically relevant confounding variables cannot be adequately evaluated. These include retrospective assessment of activity, endoscopic (not symptom) activity, duration of disease, anatomic extent, family history of LBW/SGA, nutritional status and smoking. We intended to performed sub-analyses for the case definition, (as reported in the Results) disease activity definitions, follow-up duration and protocol but there were too few similarly defined parameters within the included studies to further sub-group these for analyses. For some outcomes, less than 5 studies were suitable for meta-analysis, which may limit the application of the results to the pregnant IBD population as a whole.

The presence of active IBD during pregnancy is a risk factor for both SGA and LBW in women with IBD. Independent of disease activity, thiopurine use does not increase the risk of either SGA or LBW. These conclusions should be factored-into discussion with pregnant women about maintenance therapies during pregnancy. Future studies on these relationships should define disease activity according to standard criteria (e.g., Mayo score), and control for disease activity when assessing the impact of medications on pregnancy outcomes.

The pregnancy outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients are an important topic for physicians and patients. The drug exposure effect and the influence of active disease on low birth weight (LBW) and/or small gestational age (SGA) are not yet well-known. In fact, many women become non-adherent to medications during pregnancy, for fear of a negative effect on the fetus So further information would be useful in counseling IBD pregnancy women.

Several retrospective case-control studies have reported an increase of preterm delivery, LBW, SGA or congenital abnormalities in patients with IBD, when compared to healthy controls. These conclusions have been confounded by the individual roles that disease activity and maintenance medications may play in these birth outcomes.

In the present meta-analysis, we have observed that the presence of active IBD during pregnancy is a risk factor for SGA and LBW in women with IBD. Independent of disease activity, thiopurine use does not increase the risk of either SGA or LBW. These conclusions should be factored-into discussion with pregnant women about maintenance therapies during pregnancy.

Since to women with IBD who are pregnant have a higher risk of adverse events, early consultation with specialists can help them to plan appropriate pregnancy and delivery. Future studies on these relationships should define disease activity according to standard criteria (e.g., Mayo score), and control for disease activity when assessing the impact of medications on pregnancy outcomes.

This systematic review and meta-analysis adds useful information for practice and research.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Khajehei M, Petretta M, Zhang XQ S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Fonager K, Sørensen HT, Olsen J, Dahlerup JF, Rasmussen SN. Pregnancy outcome for women with Crohn’s disease: a follow-up study based on linkage between national registries. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2426-2430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dominitz JA, Young JC, Boyko EJ. Outcomes of infants born to mothers with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:641-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nørgård B, Fonager K, Sørensen HT, Olsen J. Birth outcomes of women with ulcerative colitis: a nationwide Danish cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3165-3170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cornish J, Tan E, Teare J, Teoh TG, Rai R, Clark SK, Tekkis PP. A meta-analysis on the influence of inflammatory bowel disease on pregnancy. Gut. 2007;56:830-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 325] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nørgård B, Hundborg HH, Jacobsen BA, Nielsen GL, Fonager K. Disease activity in pregnant women with Crohn’s disease and birth outcomes: a regional Danish cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1947-1954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Moser MA, Okun NB, Mayes DC, Bailey RJ. Crohn’s disease, pregnancy, and birth weight. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1021-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bortoli A, Pedersen N, Duricova D, D’Inca R, Gionchetti P, Panelli MR, Ardizzone S, Sanroman AL, Gisbert JP, Arena I, Riegler G, Marrollo M, Valpiani D, Corbellini A, Segato S, Castiglione F, Munkholm P; European Crohn-Colitis Organisation (ECCO) Study Group of Epidemiologic Committee (EpiCom). Pregnancy outcome in inflammatory bowel disease: prospective European case-control ECCO-EpiCom study, 2003-2006. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:724-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Julsgaard M, Nørgaard M, Hvas CL, Buck D, Christensen LA. Self-reported adherence to medical treatment prior to and during pregnancy among women with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1573-1580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ellul P, Zammita SC, Katsanos KH, Cesarini M, Allocca M, Danese S, Karatzas P, Moreno SC, Kopylov U, Fiorino G. Perception of Reproductive Health in Women with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:886-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nørgård B, Pedersen L, Fonager K, Rasmussen SN, Sørensen HT. Azathioprine, mercaptopurine and birth outcome: a population-based cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:827-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Coelho J, Beaugerie L, Colombel JF, Hébuterne X, Lerebours E, Lémann M, Baumer P, Cosnes J, Bourreille A, Gendre JP, Seksik P, Blain A, Metman EH, Nisard A, Cadiot G, Veyrac M, Coffin B, Dray X, Carrat F, Marteau P; CESAME Pregnancy Study Group (France). Pregnancy outcome in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with thiopurines: cohort from the CESAME Study. Gut. 2011;60:198-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Langagergaard V, Pedersen L, Gislum M, Nørgard B, Sørensen HT. Birth outcome in women treated with azathioprine or mercaptopurine during pregnancy: A Danish nationwide cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:73-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | O’Toole A, Nwanne O, Tomlinson T. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Increases Risk of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:2750-2761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Davey J, Turner RM, Clarke MJ, Higgins JP. Characteristics of meta-analyses and their component studies in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews: a cross-sectional, descriptive analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Reprint--preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Phys Ther. 2009;89:873-880. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Meerpohl J, Norris S. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:401-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4091] [Cited by in RCA: 5709] [Article Influence: 407.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | DerSimonian R, Laird N. “Meta-analysis in clinical trials.”. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177-188. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26739] [Cited by in RCA: 30428] [Article Influence: 780.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39087] [Cited by in RCA: 46547] [Article Influence: 2115.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 19. | Bröms G, Granath F, Linder M, Stephansson O, Elmberg M, Kieler H. Birth outcomes in women with inflammatory bowel disease: effects of disease activity and drug exposure. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1091-1098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bush MC, Patel S, Lapinski RH, Stone JL. Perinatal outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004;15:237-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | de Lima-Karagiannis A, Zelinkova-Detkova Z, van der Woude CJ. The Effects of Active IBD During Pregnancy in the Era of Novel IBD Therapies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1305-1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shim L, Eslick GD, Simring AA, Murray H, Weltman MD. The effects of azathioprine on birth outcomes in women with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:234-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cleary BJ, Källén B. Early pregnancy azathioprine use and pregnancy outcomes. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2009;85:647-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bortlik M, Machkova N, Duricova D, Malickova K, Hrdlicka L, Lukas M, Kohout P, Shonova O, Lukas M. Pregnancy and newborn outcome of mothers with inflammatory bowel diseases exposed to anti-TNF-α therapy during pregnancy: three-center study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:951-958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Komoto S, Motoya S, Nishiwaki Y, Matsui T, Kunisaki R, Matsuoka K, Yoshimura N, Kagaya T, Naganuma M, Hida N. Pregnancy outcome in women with inflammatory bowel disease treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor and/or thiopurine therapy: a multicenter study from Japan. Intest Res. 2016;14:139-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mahadevan U, Martin CF, Sandler RS, Kane SV, Dubinsky M, Lewis JD, Sandborn WJ, Sands BE. “PIANO: A 1000 Patient Prospective Registry of Pregnancy Outcomes in Women with IBD Exposed to Immunomodulators and Biologic Therapy,”. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:S-149. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Stephansson O, Larsson H, Pedersen L, Kieler H, Granath F, Ludvigsson JF, Falconer H, Ekbom A, Sørensen HT, Nørgaard M. Congenital abnormalities and other birth outcomes in children born to women with ulcerative colitis in Denmark and Sweden. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:795-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Molnár T, Farkas K, Nagy F, Lakatos PL, Miheller P, Nyári T, Horváth G, Szepes Z, Marik A, Wittmann T. Pregnancy outcome in patients with inflammatory bowel disease according to the activity of the disease and the medical treatment: a case-control study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1302-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nielsen OH, Andreasson B, Bondesen S, Jarnum S. Pregnancy in ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1983;18:735-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Van Assche G, Dignass A, Reinisch W, van der Woude CJ, Sturm A, De Vos M, Guslandi M, Oldenburg B, Dotan I, Marteau P, Ardizzone A, Baumgart DC, D’Haens G, Gionchetti P, Portela F, Vucelic B, Söderholm J, Escher J, Koletzko S, Kolho KL, Lukas M, Mottet C, Tilg H, Vermeire S, Carbonnel F, Cole A, Novacek G, Reinshagen M, Tsianos E, Herrlinger K, Oldenburg B, Bouhnik Y, Kiesslich R, Stange E, Travis S, Lindsay J; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO). The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: Special situations. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:63-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 569] [Cited by in RCA: 547] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mahadevan U, Sandborn WJ, Li DK, Hakimian S, Kane S, Corley DA. Pregnancy outcomes in women with inflammatory bowel disease: a large community-based study from Northern California. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1106-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Abhyankar A, Ham M, Moss AC. Meta-analysis: the impact of disease activity at conception on disease activity during pregnancy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:460-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Conti J, Abraham S, Taylor A. “Eating behavior and pregnancy outcome.,”. J Psychosom Res. 1998;44:465-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Mesa F, Pozo E, O’Valle F, Puertas A, Magan-Fernandez A, Rosel E, Bravo M. Relationship between periodontal parameters and plasma cytokine profiles in pregnant woman with preterm birth or low birth weight. Clin Oral Investig. 2016;20:669-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wang H, Hu YF, Hao JH, Chen YH, Su PY, Wang Y, Yu Z, Fu L, Xu YY, Zhang C. Maternal zinc deficiency during pregnancy elevates the risks of fetal growth restriction: a population-based birth cohort study. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |