Published online Nov 14, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i42.7644

Peer-review started: July 6, 2017

First decision: July 28, 2017

Revised: August 14, 2017

Accepted: August 25, 2017

Article in press: August 25, 2017

Published online: November 14, 2017

Processing time: 129 Days and 6.7 Hours

To determine the vaccination rates in pediatric immunosuppression-dependent inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and review the safety and efficacy of vaccinations in this population.

The electronic medical records from October 2009 to December 2015 of patients diagnosed with IBD at 10 years of age or younger and prescribed anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNF-α) therapy were reviewed for clinical history, medication history, vaccination history, and hepatitis B and varicella titers. Literature discussing vaccination response in IBD patients were identified through search of the MEDLINE database and reviewed using the key words “inflammatory bowel disease”, “immunization”, “vaccination”, “pneumococcal”, “varicella”, and “hepatitis B”. Non-human and non-English language studies were excluded. Search results were reviewed by authors to select articles that addressed safety and efficacy of immunizations in inflammatory bowel disease.

A total of 51 patients diagnosed with IBD prior to the age of 10 and receiving anti-TNF-α therapy were identified. Thirty-three percent of patients (17/51) had incomplete or no documentation of vaccinations. Sixteen case reports, cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, and randomized trials were determined through review of the literature to describe the safety and efficacy of hepatitis B, pneumococcal, and varicella immunizations in adult and pediatric patients with IBD. These studies showed that patients safely tolerated the vaccines without significant adverse effects. Importantly, IBD patients receiving immunosuppressive medications, particularly anti-TNF-α treatment, have decreased vaccine response compared to controls. However, the majority of patients are still able to achieve protective levels of specific antibodies.

Immunizations have been shown to be well-tolerated and protective immunity can be achieved in patients with IBD requiring immunosuppressive therapy.

Core tip: Chronic immunosuppression and immune defects can contribute to increased susceptibility to infections in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Immunization rates among IBD patients are low due to concerns about vaccine efficacy while on immunosuppression and disease exacerbation with administration. The aim of this review was to determine the vaccination rates in pediatric immunosuppression-dependent IBD and the safety and efficacy of immunizations in this population.

- Citation: Nguyen HT, Minar P, Jackson K, Fulkerson PC. Vaccinations in immunosuppressive-dependent pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(42): 7644-7652

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i42/7644.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i42.7644

The prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is on the rise, particularly in the elderly population and very young children. Approximately 25% of patients with IBD will be diagnosed during childhood, and very early-onset IBD (VEOIBD) further classifies those children diagnosed before 6 years of age. VEOIBD comprises 15% of pediatric IBD cases and has an incidence rate of 4.37 per 100000 children and a prevalence of 14 per 100000 children[1]. The increasing incidence in the very young is of interest to immunologists as these patients often are referred for evaluation for immunodeficiency. Conventional, polygenic IBD predominates in patients aged 7 years and older at time of diagnosis, but approximately 20% of VEOIBD is monogenic-single gene defects that affect the gastrointestinal immune regulation. Mutations that result in chronic granulomatous disease, IL-10 signaling alterations, and defects in X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis function have been associated with VEOIBD[1]. These abnormalities in innate immunity are further compounded by immunosuppressive medications prescribed for IBD treatment, resulting in increased risk of infection. A cross-sectional analysis showed that bacterial pneumonia was one of the most common causes of hospitalizations for IBD patients on immunomodulators or anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNF-alpha) therapy with a prevalence of S. pneumoniae pneumonia at 82.6 per 100000 compared to 69.2 per 100000 in controls[2]. Adult IBD patients have an increased risk of pneumonia (OR = 1.54, 95%CI: 1.49-1.60) compared to matched individuals without IBD with use of immunosuppressive therapies like biologics (OR = 1.32, 95%CI: 1.11-1.57) and corticosteroids (OR = 1.91, 95%CI: 1.72-2.12) as a risk factor[3]. VEOIBD children in particular are at increased risk for vaccine-preventable infections, as many may have not yet completed their primary vaccination series prior to starting immunosuppressive therapies such as immunomodulators or anti-TNF-α.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends that patients with chronic inflammatory diseases treated with long-term immunosuppression receive inactive vaccinations, such as pneumococcal vaccines, per standard immunization schedules[4]. Despite these recommendations, vaccination rates among IBD patients are lower than expected. In a study of 169 adult IBD patients, only 10% of participants received recommended pneumococcal vaccines[5]. Common reasons among patients for decreased adherence with vaccination recommendations have included belief in poor efficacy of vaccines, lack of knowledge about vaccine guidelines, and fear of disease exacerbation with vaccine administration[5].

The primary aim of our study was to determine the vaccination rates among pediatric patients with immunosuppression-dependent IBD at our institution by retrospectively reviewing the electronic medical records from October 2009 through December 2015 at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC). Additionally, we systematically reviewed the literature.

Pediatric patients with a diagnosis of IBD made prior to the age of 10 years and receiving anti-TNF-alpha were identified at CCHMC. We included patients diagnosed prior to age 10 to ensure capture of patients with possible monogenic disease. The electronic medical records for the patients, dated from October 2009 to December 2015, were retrospectively reviewed. Information including clinical history, exam findings, patient’s IBD status, results of esophagogastroduodenoscopy and/or colonoscopy with biopsies, vaccination records, medication records, vaccine titers, and infectious disease laboratory testing results were collected. This study was approved by the CCHMC Institutional Review Board.

The MEDLINE database was searched through PubMed with search strategies as detailed in (Table 1). Search results were reviewed by the primary research participants to determine if articles addressed safety and efficacy of immunizations in inflammatory bowel disease and other immunomodulator-dependent diseases. Articles were limited to randomized trials, case-control studies, cohort studies, and reviews. Childhood and adult immunizations to pneumococcal, Hepatitis B, and varicella with any dose and any schedule were included. Non-human and non-English language studies were excluded.

| Search terms | Search limitation | Number of search results |

| “inflammatory bowel disease” + “immunization” | Limited to human species and English language | 436 |

| “inflammatory bowel disease” + “vaccination” | Limited to human species and English language | 284 |

| “inflammatory bowel disease” + “pneumococcal” | Limited to human species and English language | 44 |

| “inflammatory bowel disease” + “Hepatitis B” | Limited to human species and English language | 181 |

| “inflammatory bowel disease” + “varicella” | Limited to human species and English language | 68 |

| “immunosuppression” + “pneumococcal” | Limited to human species and English language | 191 |

| “immunosuppression” + “Hepatitis B” + “vaccination” | Limited to human species and English language | 141 |

| “immunosuppression” + “varicella” + “vaccination” | Limited to human species and English language | 71 |

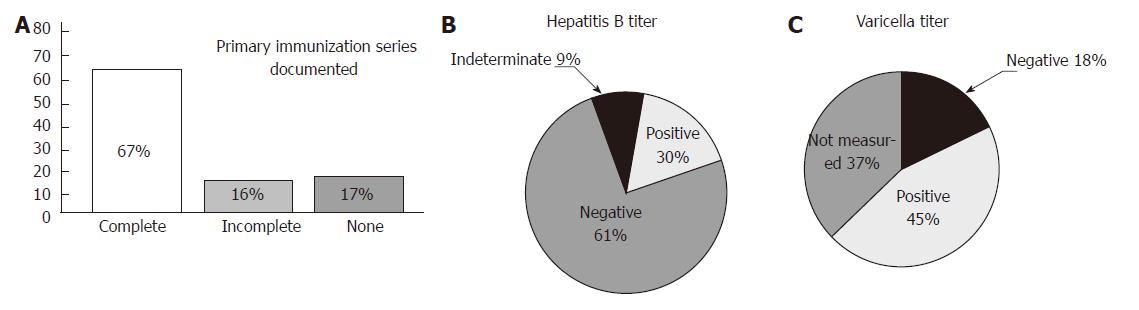

A total of 51 pediatric patients with a diagnosis of IBD made prior to the age of 10 years and receiving anti-TNF-α were identified. The age at diagnosis for these 51 patients ranged from 15 mo to 9 years of age. Sixty-seven percent (34/51) had documentation of a completed primary vaccination series (Figure 1A). The remainder of the patients had no or incomplete documentation of immunizations.

Hepatitis B (HepB) serology has been recommended prior to initiation of immunosuppressive therapies due to the risk of reactivation of latent HepB infection with the start of treatment[6,7]. Additionally, it is recommended that non-immune HepB patients receive a vaccine booster[8]. In our retrospective study, serology specifically evaluating HepB surface antibody showed that 67% (27/44 patients who had documented serology) were non-responders to their initial HepB vaccine series (Figure 1B). Six of the non-responders (6/27) had documentation of HepB vaccine booster receipt and post-vaccination titers drawn. Four of the 6 achieved seroprotection following the booster vaccine. Eighteen of the non-responders (18/27) either did not receive HepB vaccine booster or did not have repeat HepB titers measured.

With increasing use of immunomodulatory therapy in the management of IBD, evaluation of varicella immunity is also recommended as primary infection can be severe and life-threatening in immunocompromised hosts. Twenty-eight percent (9/32) of patients who had varicella antibodies measured had negative titers (Figure 1C). We found that 4 of the 9 patients had only one varicella vaccine administration documented.

The efficacy of immunizations in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases requiring immunosuppressive therapies has been an area of concern. Studies involving rheumatologic disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematous, have shown that immunizations are well tolerated and do not exacerbate disease activity[9,10]. Further studies demonstrate that patients with rheumatologic diseases receiving immunosuppressive therapies may have a decreased response to immunizations but are still able to mount a specific-antibody response to vaccinations[11-15]. Interestingly, Kapetanovic et al. proposed the possibility of anti-TNF-α therapy enhancing the immune response as rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving anti-TNF monotherapy in this cohort had a serum response to pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) that was similar to that of healthy controls[16]. In addition, anti-pneumococcal protective titers were sustained as long as 10 years following administration of the PPSV23 in patients with autoimmune inflammatory disease[17]. In a randomized controlled study with 103 adult rheumatoid arthritis patients, the effects of systemic immunosuppression on vaccine responses were evaluated. Patients treated with both methotrexate and rituximab had decreased response to PPSV23, a T-independent antigen, compared to patients treated with methotrexate alone. However, over half of the patients receiving adjunctive therapy with rituximab responded to at least one of the pneumococcal serotypes. Additionally, there was no difference in response to the T-dependent antigens, such as the tetanus toxoid, between the two treatment groups[18]. These results support the increased antigenicity of and improved response to vaccines containing T-dependent antigens in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases receiving immunosuppressive therapy.

The vaccine response in adult IBD patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapies is similar to those of rheumatologic patients (Table 2). In general, adult IBD patients have decreased magnitude of response to PPSV23/pneumococcal conjugate (PCV13) and HepB vaccines, but most patients retain their specific antibody response and can attain protective titer levels. The main difference between the findings of vaccine efficacy studies in rheumatologic patients and IBD patients was that anti-TNF therapy was associated with a higher risk of reduced response. However, IBD patients receiving anti-TNF treatment were still able to achieve protective levels of specific antibodies. An accelerated, double-dose HepB immunization series has been shown to be efficacious, wherein patients receive double doses of the vaccine 3 times at one-month intervals[19]. When combined with booster immunization in non-responders, the majority of IBD patients can attain seroprotection[19]. Additionally, PCV13, a T-dependent vaccine, was associated with increased titers compared to PPSV23[20]. These findings also apply to the Hepatitis A vaccine[21]. Vaccinations were overall well-tolerated and were not associated with adverse reactions such as exacerbation of the underlying inflammatory disease[20,22-24].

| Ref. | Study design | Subjects (n.) | Comparison groups | Outcome measured | Adverse events | Effects |

| Andrade et al[38], 2015 | Retrospective cohort | 217 | IBD patients treated with infliximab and/or azathioprine | Hepatitis B antibodies 1-3 mo after HepB series completion | No comment on adverse effects | Receipt of vaccination while under infliximab or azathioprine treatment resulted in decreased seroconversion (OR = 17.6, 95%CI: 8.5-33.9 and OR = 3.3, 95%CI: 1.6-9.1) |

| Cosio-Gil et al[39], 2015 | Retrospective cohort | 172 | IBD patients | Hepatitis B antibodies 1-3 mo after HepB series completion | No comment on adverse effects | 50.6% patients responded to 1st series (95%CI: 42.9-58.3) 66.8% patients responded to 1st or 2nd series (95%CI: 59.3-73.8) Older age associated with decreased response (for patients > 55 yr, OR = 3.6, 95%CI: 1.3-10.2) |

| Cekic et al[40], 2015 | Retrospective cohort | 125 | IBD patients | Hepatitis B antibodies 1 mo after HepB series completion | No comment on adverse effects | Age over 45 years, active disease, CD subtype, and immune suppression negatively impacted vaccine response |

| Ben Musa et al[41], 2014 | Retrospective, cross-sectional | 500 | IBD patients | Hepatitis B antibodies | No comment on adverse effects | Younger age associated with increased HepB vaccine response |

| Sempere et al[24] 2013 | Retrospective cohort | 105 | IBD patients | Hepatitis B antibodies 1-3 mo after HepB series completion | No significant adverse events associated with vaccination | Ileal CD (P = 0.01), long-standing IBD (P = 0.03), low albumin (P = 0.02), and systemic steroid use with more than one dose (P = 0.02) associated with decreased response |

| Altunoz et al[42], 2012 | Retrospective cohort | 211-159 patients with IBD, 52 healthy controls | IBD patients and healthy controls | Hepatitis B antibodies at least 1 month after HepB series completion | No comment on adverse events | Diagnosis of IBD overall (P < 0.001), male sex among IBD patients (P = 0.01), immunosuppressive therapy (P < 0.001), and active disease (P < 0.001) associated with decreased response |

| Gisbert et al[19], 2012 | Prospective cohort | 241 | IBD patients | Hepatitis B antibodies 1-3 mo after HepB series (accelerated schedule or double dose) completion | No direct comment on adverse events | Older age (OR = 0.96, 95%CI: 0.94-0.98, P < 0.001) and anti-TNF therapy (OR = 0.39, 95%CI: 0.20-0.76, P < 0.01) associated with decreased rate of seroconversion 65% of participants responded after the 1st or 2nd series |

| Kantsǿ et al[20], 2015 | Randomized trial | 157 | CD patients receiving PCV13 vs PPV23 | Specific antibody response to 12 pneumococcal serotypes 1 mo after vaccination | No significant adverse events related to vaccination | PCV13 induced higher post-immunization titers for 5 serotypes (P < 0.05), regardless of treatment Immunosuppressive treatment with or without anti-TNF-α impaired immune response to both vaccines |

| Lee et al[23], 2014 | Prospective cohort | 197 | CD patients | Antibody response 1 mo after PPSV23 | No serious adverse effects in study | Female gender and anti-TNF therapy (monotherapy or combination with immunomodulator) associated with decreased response |

| Fiorino et al[22], 2012 | Prospective cohort | 96 | IBD patients | Antibody response 3 wk after PPSV23 | No serious adverse effects in the study | Infliximab only and combination therapy associated with decreased response (P = 0.009 and P = 0.038, respectively) |

| Melmed et al[43], 2010 | Prospective cohort | 64-45 patients with IBD, 19 healthy controls | A) IBD patients not receiving immunosuppressive therapy B) IBD patients receiving immunosuppression C) Healthy controls | Specific antibody response to 5 pneumococcal serotypes 4 wk after PPSV23 | No comments on adverse effects | Combination immunosuppression associated with decreased response rate (P ≤ 0.01) |

The efficacy and safety of primary vaccinations in pediatric IBD patients has been investigated in a limited number of studies (Table 3). The Hepatitis A vaccine series is highly immunogenic in pediatric IBD patients with seroconversion rates over 90% and has no significant differences in response between case patients compared to healthy controls; the vaccine was also well tolerated[25-27]. The HepB series does not have the same immunogenicity as Hepatitis A (Table 3). Pediatric IBD patients were shown to have decreased seroconversion rate following the completion of the 3-dose series compared to controls, but the majority, over 70%, still seroconverted[27,28]. PCV13 is commonly encountered in pediatric clinics compared to PPSV23 since the conjugate vaccine is fundamental to the primary vaccine series. Banaszkiewics et al. demonstrated that pediatric IBD patients have a good response to PCV13, further supporting that T-cell immunity seems to be conserved in IBD patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy and that T-dependent vaccines may be preferential to T-independent vaccines in these patients[29].

| Ref. | Study design | Subjects (n) | Comparison groups | Outcome measured | Adverse effects | Effects |

| Urganci et al[27], 2013 | Prospective cohort | 97-47 with IBD, 50 healthy controls | IBD patients and healthy controls | Hepatitis A and hepatitis B antibodies 1 month following hepatitis A vaccine and hepB series | No severe adverse reactions associated with vaccination | All participants seroconverted to hepatitis A IBD patients had decreased seroconversion to Hepatitis B (70.2% vs 90% in healthy controls, P = 0.02) No statistically significant association between treatment and vaccination response |

| Moses et al[27], 2012 | Prospective, cross-sectional | 100 IBD patients | IBD patients receiving infliximab | Hepatitis B immunity (anti-HBs ≥ 10 IU/mL) | No comments on adverse effects | Older age at diagnosis and study visit, pancolitis, and lower albumin levels associated with non-immunity (P < 0.05) Infliximab dose, duration, frequency did not affect baseline immunity; associated with decreased immunity to booster |

| Fallahi et al[44], 2014 | Prospective cohort | 38-18 with IBD; 20 healthy controls | A: IBD patients not receiving immunosuppressive therapy B: IBD patients receiving immunosuppression C: Healthy controls | Increase in total IgG 28 d after PPSV23 vaccination and percentage of switched memory B cells | No comments on adverse effects | IBD associated with decreased percentage of switched memory B cells and lower increase in total IgG level (P = 0.007 and P = 0.001, respectively) |

| Banaszkiewicz et al[29] , 2015 | Prospective cohort | 178-122 with IBD; 56 healthy controls | A: IBD patients not receiving immunosuppressive therapy B: IBD patients receiving immunosuppression C: Healthy controls | Specific antibody response 6-8 wk following 1 dose of PCV13 | No serious adverse effects related to PCV13 | Adequate vaccine response achieved in all participants (90.4% in IBD patients vs 96.5% in controls) with no significant difference between IBD patients and controls (P = 0.53) Immunosuppressive therapy associated with decreased rise in geometric mean titers (P = 0.04) |

Live vaccines have long been contraindicated in immunocompromised hosts. However, with the immunocompromised state comes increased risk of contracting infections prevented by these vaccines. Herpes zoster can occur in 20%-50% of patients following bone marrow transplant[30]. Crohn’s disease (varicella OR = = 12.75; 95%CI: 8.30-19.59; herpes zoster OR = = 7.91; 95%CI: 5.60-11.18) and ulcerative colitis (varicella OR = = 4.25; 95%CI: 1.98-9.12; herpes zoster OR = = 3.90; 95%CI: 1.98-7.67) in pediatric patients have an increased association with hospitalizations for varicella or herpes zoster[30]; thus, there is great interest in determining whether live vaccines are safe for pediatric patients with IBD on immunosuppressive therapy. Lu et al[32] illustrated the safety and efficacy of the varicella vaccine in IBD patients on immunosuppressive therapies in a case series report. Three of the patients were on 6-mercaptopurine and tolerated the varicella vaccine without issue, developing equivocal or greater immunity. Two patients received the varicella vaccine while on infliximab, albeit inadvertently, without issue and developed positive titers to the virus.

The safety of live vaccines in other pediatric populations receiving immunosuppression has been investigated. Sauerbrei et al[30] studied the efficacy and safety of the varicella vaccine in children after bone marrow transplant. Fifteen patients received the varicella vaccine 12-23 mo (median 18 mo) after transplant. Notably, the study participants were within 1-2 years of transplantation during which time some degree of immune dysfunction is expected, but they were not receiving immunosuppression and their lymphocyte counts had to be greater than 1000/μL with T cell counts greater than 700/μL. Importantly, no study participant experienced adverse events related to the varicella vaccine. Nine of the participants were seronegative prior to the vaccine, and 8 of the 9 seroconverted within 6 mo of vaccine administration. The remaining patient required a second dose of the vaccine, after which seroconversion was achieved within 6 months. Only 3 study participants had unchanged titers. Machado et al[34] also demonstrated that the measles, mumps, rubella vaccine was overall well tolerated in bone marrow transplant patients[33]. In addition, the varicella vaccine was found to be safe in juvenile rheumatic patients receiving methotrexate or corticosteroids.

These results suggest that live vaccines may be tolerated in patients receiving long-term immunosuppressive therapies, particularly in those without severe immune defects. However, this topic remains controversial, and the support for administering live vaccines in patients receiving immunosuppressive therapies is very limited and consists of small cohort or case series studies. Further studies are needed to confirm the safety of live vaccinations in an immunosuppressed population, which would greatly benefit from them.

Children with a diagnosis of IBD early in life are at significant risk of infection due to their immunosuppression from both their underlying disease and treatment. These patients will require years, if not a lifetime, of immunosuppressive therapy, and such regimens may be started prior to completion of their primary vaccination series due to their young age at diagnosis, augmenting their risk of infection. IBD patients in general have decreased vaccinations rates[35]. Working with allergists and immunologists, a thorough auditing of immunizations and measurement of antibodies to vaccine-preventable microbes at time of diagnosis can be achieved. Further, immunologists can update immunizations and ensure appropriate antibody response to provide protection in this growing, vulnerable population. To assess seroconversion and seroprotection to an immunization, specific serum antibody levels measured prior to and approximately four to eight weeks following vaccine administration are recommended[36]. Although booster vaccinations or completion of immunizations may not be possible prior to starting immunosuppressive treatment, studies have shown that these patients can still mount an immune response to vaccines, particularly to T-dependent antigens, until seroprotective status is achieved. Optimal vaccination schedules and long-term immunogenicity of these vaccines remain to be studied in pediatric IBD patients. In addition, considering their unique immune dysregulation, further studies in the efficacy of immunizations in pediatric IBD patients, especially in the very young, are needed.

The population of young children affected by inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is growing. This disease is oftentimes complicated by immune defects and long-term immunosuppressive therapy, resulting in an increased susceptibility to infections. Updating vaccines at diagnosis or before initiating chronic immunosuppressive therapy would be ideal; however, this is often not achievable due to young age and the necessity to initiate treatment imminently. Immunization rates among IBD patients are lower with the efficacy of immunizations while receiving immunosuppression and the fear of disease exacerbation after vaccine administration negatively impacting rates. The aim of this review is to determine the vaccination rates in pediatric immunosuppression-dependent IBD and the safety and efficacy of immunizations in this population.

The prevalence of IBD is on the rise, particularly in very young children. Approximately 25% of patients with IBD will be diagnosed during childhood, and very early-onset IBD (VEOIBD) further classifies those children diagnosed before 6 years of age and comprises 15% of pediatric IBD cases. As elucidated by Uhlig et al in 2014, VEOIBD has been associated with single gene defects affecting the gastrointestinal immune regulation in 20% of cases. This emerging population has posed diagnostic and management challenges for both gastroenterologists and immunologists. In addition to innate immunity abnormalities, these patients require long-term immunosuppression, including anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNF-α) therapies, for treatment. These factors contribute to an increased risk of infection.

Due to the young age at the time of diagnosis, patients with VEOIBD may not be able to complete their primary vaccination series prior to initiation of immunosuppressive therapies, which further exacerbates the increased risk of infection. The rate of vaccinations in addition to the safety and efficacy of immunizations has been studied in adult and, to a lesser extent, pediatric IBD patients. Literature discussing vaccination response in IBD patients were identified through search of the MEDLINE database and reviewed by the authors.

This review shows that vaccinations are well-tolerated in IBD patients, and protective immunity can be achieved in those receiving immunosuppression. Immunologists can help provide an auditing of immunizations and can ensure appropriate antibody response to provide protection in this vulnerable population.

VEOIBD classifies children diagnosed with IBD at age 6 years or younger and is associated with single gene defects affecting gastrointestinal immune regulation in 20% of cases. Anti-TNF-α therapies, which include infliximab and adalimumab, are monoclonal antibodies that inhibit the inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) contains thirteen serotypes of pneumococcus and elicits an immune response dependent on T-cells. Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) contains 23 pneumococcal serotypes and incites production of specific antibodies independent of T-cells.

In this systematic review, the authors detailed the safety and efficacy of vaccinations in pediatric IBD.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Katsanos KH, Suzuki H, Rocha R S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Uhlig HH, Schwerd T, Koletzko S, Shah N, Kammermeier J, Elkadri A, Ouahed J, Wilson DC, Travis SP, Turner D. The diagnostic approach to monogenic very early onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:990-1007.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 452] [Cited by in RCA: 476] [Article Influence: 43.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Stobaugh DJ, Deepak P, Ehrenpreis ED. Hospitalizations for vaccine preventable pneumonias in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a 6-year analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2013;6:43-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Long MD, Martin C, Sandler RS, Kappelman MD. Increased risk of pneumonia among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:240-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rubin LG, Levin MJ, Ljungman P, Davies EG, Avery R, Tomblyn M, Bousvaros A, Dhanireddy S, Sung L, Keyserling H. 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:e44-e100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 510] [Cited by in RCA: 590] [Article Influence: 49.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Melmed GY, Ippoliti AF, Papadakis KA, Tran TT, Birt JL, Lee SK, Frenck RW, Targan SR, Vasiliauskas EA. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease are at risk for vaccine-preventable illnesses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1834-1840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Esteve M, Saro C, González-Huix F, Suarez F, Forné M, Viver JM. Chronic hepatitis B reactivation following infliximab therapy in Crohn’s disease patients: need for primary prophylaxis. Gut. 2004;53:1363-1365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 331] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ojiro K, Naganuma M, Ebinuma H, Kunimoto H, Tada S, Ogata H, Iwao Y, Saito H, Hibi T. Reactivation of hepatitis B in a patient with Crohn’s disease treated using infliximab. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:397-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lu Y, Bousvaros A. Immunizations in children with inflammatory bowel disease treated with immunosuppressive therapy. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2014;10:355-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Elkayam O, Yaron M, Caspi D. Safety and efficacy of vaccination against hepatitis B in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:623-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mercado U. Why have rheumatologists been reluctant to vaccinate patients with systemic lupus erythematosus? J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1469-1471. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Brezinschek HP, Hofstaetter T, Leeb BF, Haindl P, Graninger WB. Immunization of patients with rheumatoid arthritis with antitumor necrosis factor alpha therapy and methotrexate. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20:295-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Elkayam O, Paran D, Caspi D, Litinsky I, Yaron M, Charboneau D, Rubins JB. Immunogenicity and safety of pneumococcal vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:147-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kasapçopur O, Cullu F, Kamburoğlu-Goksel A, Cam H, Akdenizli E, Calýkan S, Sever L, Arýsoy N. Hepatitis B vaccination in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1128-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mease PJ, Ritchlin CT, Martin RW, Gottlieb AB, Baumgartner SW, Burge DJ, Whitmore JB. Pneumococcal vaccine response in psoriatic arthritis patients during treatment with etanercept. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1356-1361. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Visvanathan S, Keenan GF, Baker DG, Levinson AI, Wagner CL. Response to pneumococcal vaccine in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis receiving infliximab plus methotrexate or methotrexate alone. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:952-957. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Kapetanovic MC, Saxne T, Sjöholm A, Truedsson L, Jönsson G, Geborek P. Influence of methotrexate, TNF blockers and prednisolone on antibody responses to pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45:106-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Broyde A, Arad U, Madar-Balakirski N, Paran D, Kaufman I, Levartovsky D, Wigler I, Caspi D, Elkayam O. Longterm Efficacy of an Antipneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine among Patients with Autoimmune Inflammatory Rheumatic Diseases. J Rheumatol. 2016;43:267-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bingham CO 3rd, Looney RJ, Deodhar A, Halsey N, Greenwald M, Codding C, Trzaskoma B, Martin F, Agarwal S, Kelman A. Immunization responses in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with rituximab: results from a controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:64-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gisbert JP, Villagrasa JR, Rodríguez-Nogueiras A, Chaparro M. Efficacy of hepatitis B vaccination and revaccination and factors impacting on response in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1460-1466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kantso B, Halkjær SI, Thomsen OØ, Belard E, Gottschalck IB, Jørgensen CS, Krogfelt KA, Slotved HC, Ingels H, Petersen AM. Immunosuppressive drugs impairs antibody response of the polysaccharide and conjugated pneumococcal vaccines in patients with Crohn’s disease. Vaccine. 2015;33:5464-5469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Park SH, Yang SK, Park SK, Kim JW, Yang DH, Jung KW, Kim KJ, Ye BD, Byeon JS, Myung SJ. Efficacy of hepatitis A vaccination and factors impacting on seroconversion in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:69-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fiorino G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Naccarato P, Szabò H, Sociale OR, Vetrano S, Fries W, Montanelli A, Repici A, Malesci A. Effects of immunosuppression on immune response to pneumococcal vaccine in inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1042-1047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 23. | Lee CK, Kim HS, Ye BD, Lee KM, Kim YS, Rhee SY, Kim HJ, Yang SK, Moon W, Koo JS, Lee SH, Seo GS, Park SJ, Choi CH, Jung SA, Hong SN, Im JP, Kim ES; Korean Association for the Study of Intestinal Diseases (KASID) Study. Patients with Crohn’s disease on anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy are at significant risk of inadequate response to the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:384-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sempere L, Almenta I, Barrenengoa J, Gutiérrez A, Villanueva CO, de-Madaria E, García V, Sánchez-Payá J. Factors predicting response to hepatitis B vaccination in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Vaccine. 2013;31:3065-3071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Moses J, Alkhouri N, Shannon A, Feldstein A, Carter-Kent C. Response to hepatitis A vaccine in children with inflammatory bowel disease receiving infliximab. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:E160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Radzikowski A, Banaszkiewicz A, Łazowska-Przeorek I, Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk U, Woś H, Pytrus T, Iwańczak B, Kowalska-Duplaga K, Fyderek K, Gawrońska A. Immunogenecity of hepatitis A vaccine in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1117-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Urganci N, Kalyoncu D. Immunogenecity of hepatitis A and B vaccination in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:412-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Moses J, Alkhouri N, Shannon A, Raig K, Lopez R, Danziger-Isakov L, Feldstein AE, Zein NN, Wyllie R, Carter-Kent C. Hepatitis B immunity and response to booster vaccination in children with inflammatory bowel disease treated with infliximab. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:133-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Banaszkiewicz A, Targońska B, Kowalska-Duplaga K, Karolewska-Bochenek K, Sieczkowska A, Gawrońska A, Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk U, Krzesiek E, Łazowska-Przeorek I, Kotowska M. Immunogenicity of 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine in Pediatric Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1607-1614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sauerbrei A, Prager J, Hengst U, Zintl F, Wutzler P. Varicella vaccination in children after bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;20:381-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Adams DJ, Nylund CM. Hospitalization for Varicella and Zoster in Children with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Pediatr. 2016;171:140-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lu Y, Bousvaros A. Varicella vaccination in children with inflammatory bowel disease receiving immunosuppressive therapy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:562-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Machado CM, de Souza VA, Sumita LM, da Rocha IF, Dulley FL, Pannuti CS. Early measles vaccination in bone marrow transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35:787-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Pileggi GS, de Souza CB, Ferriani VP. Safety and immunogenicity of varicella vaccine in patients with juvenile rheumatic diseases receiving methotrexate and corticosteroids. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:1034-1039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Malhi G, Rumman A, Thanabalan R, Croitoru K, Silverberg MS, Hillary Steinhart A, Nguyen GC. Vaccination in inflammatory bowel disease patients: attitudes, knowledge, and uptake. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:439-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Orange JS, Ballow M, Stiehm ER, Ballas ZK, Chinen J, De La Morena M, Kumararatne D, Harville TO, Hesterberg P, Koleilat M. Use and interpretation of diagnostic vaccination in primary immunodeficiency: a working group report of the Basic and Clinical Immunology Interest Section of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:S1-S24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Robinson CL, Romero JR, Kempe A, Pellegrini C; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Child/Adolescent Immunization Work Group. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Recommended Immunization Schedule for Children and Adolescents Aged 18 Years or Younger - United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:134-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Andrade P, Santos-Antunes J, Rodrigues S, Lopes S, Macedo G. Treatment with infliximab or azathioprine negatively impact the efficacy of hepatitis B vaccine in inflammatory bowel disease patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1591-1595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Cossio-Gil Y, Martínez-Gómez X, Campins-Martí M, Rodrigo-Pendás JÁ, Borruel-Sainz N, Rodríguez-Frías F, Casellas-Jordà F. Immunogenicity of hepatitis B vaccine in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and the benefits of revaccination. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:92-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Cekic C, Aslan F, Krc A, Gümüs ZZ, Arabul M, Yüksel ES, Vatansever S, Yurtsever SG, Alper E, Ünsal B. Evaluation of factors associated with response to hepatitis B vaccination in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Ben Musa R, Gampa A, Basu S, Keshavarzian A, Swanson G, Brown M, Abraham R, Bruninga K, Losurdo J, DeMeo M. Hepatitis B vaccination in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:15358-15366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Altunöz ME, Senateş E, Yeşil A, Calhan T, Ovünç AO. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease have a lower response rate to HBV vaccination compared to controls. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1039-1044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Melmed GY, Agarwal N, Frenck RW, Ippoliti AF, Ibanez P, Papadakis KA, Simpson P, Barolet-Garcia C, Ward J, Targan SR. Immunosuppression impairs response to pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:148-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 44. | Fallahi G, Aghamohammadi A, Khodadad A, Hashemi M, Mohammadinejad P, Asgarian-Omran H, Najafi M, Farhmand F, Motamed F, Soleimani K. Evaluation of antibody response to polysaccharide vaccine and switched memory B cells in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Liver. 2014;8:24-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |