Published online Nov 14, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i42.7635

Peer-review started: August 4, 2017

First decision: August 30, 2017

Revised: September 13, 2017

Accepted: October 18, 2017

Article in press: October 19, 2017

Published online: November 14, 2017

Processing time: 102 Days and 6 Hours

To analyze predictors of healthcare-seeking behavior among Chinese patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and their satisfaction with medical care.

Participating patients met IBS Rome III criteria (excluding those with organic diseases) and were enrolled in an IBS database in a tertiary university hospital. Participants completed IBS questionnaires in face-to-face interviews. The questionnaires covered intestinal and extra-intestinal symptoms, medical consultations, colonoscopy, medications, and self-reported response to medications during the whole disease course and in the past year. Univariate associations and multivariate logistic regression were used to identify predictors for frequent healthcare-seeking behavior (≥ 3 times/year), frequent colonoscopies (≥ 2 times/year), long-term medications, and poor satisfaction with medical care.

In total, 516 patients (293 males, 223 females) were included. Participants’ average age was 43.2 ± 11.8 years. Before study enrollment, 55.2% had received medical consultations for IBS symptoms. Ordinary abdominal pain/discomfort (non-defecation) was an independent predictor for healthcare-seeking behavior (OR = 2.07, 95%CI: 1.31-3.27). Frequent colonoscopies were reported by 14.7% of patients (3.1 ± 1.4 times per year). Sensation of incomplete evacuation was an independent predictor for frequent colonoscopies (OR = 2.76, 95%CI: 1.35-5.67). During the whole disease course, 89% of patients took medications for IBS symptoms, and 14.7% reported they were satisfied with medical care. Patients with anxiety were more likely to report dissatisfaction with medical care (OR = 2.08, 95%CI: 1.20-3.59). In the past year, patients with severe (OR = 1.74, 95%CI: 1.06-2.82) and persistent (OR = 1.66, 95%CI: 1.01-2.72) IBS symptoms sought medical care more frequently.

Chinese patients with IBS present high rates of frequent healthcare-seeking behavior, colonoscopies, and medications, and low satisfaction with medical care. Intestinal symptoms are major predictors for healthcare-seeking behavior.

Core tip: The prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in the general Chinese population is about 6.5%. Many patients are dissatisfied with the efficacy of traditional IBS treatments. Data about healthcare-seeking behavior among these patients in China are lacking. We analyzed a database of patients with IBS from Peking Union Medical College Hospital to identify predictors for healthcare-seeking behavior and satisfaction with medical care among this population. We found high rates of frequent healthcare-seeking behavior, colonoscopies, and medications, and low satisfaction with medical care. Intestinal symptoms were major predictors for healthcare-seeking behavior. Anxiety influenced satisfaction with medical care.

- Citation: Fan WJ, Xu D, Chang M, Zhu LM, Fei GJ, Li XQ, Fang XC. Predictors of healthcare-seeking behavior among Chinese patients with irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(42): 7635-7643

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i42/7635.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i42.7635

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional bowel disorder with a global prevalence of 11%[1]. A meta-analysis found the pooled prevalence of IBS in a Chinese community was 6.5%[2]. Rome III criteria indicate IBS is characterized by persistent or recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort associated with altered bowel habits, and patients with IBS report lower quality of life[3]. In the United States, IBS is associated with an annual economic burden of more than 20 billion dollars (direct and indirect healthcare costs)[4]. Data from Korea in 2008 showed the annual average National Health Insurance costs for IBS per person were USD64.1, the cost for outpatient care was USD43.7, and that for inpatient care was USD1087.9[5]. A Chinese study focused on medical costs showed that IBS accounted for 3.3% of the total healthcare budget for the entire Chinese nation[6]. Data from Western countries indicated intestinal symptoms (including increasing pain severity and duration) were independently associated with seeking healthcare for IBS[7], and frequent consulters were more likely to have coexisting anxiety or depression[8]. In France, 71.9% of patients consulted their general physicians, 45.9% consulted gastroenterologists, and 8% had been hospitalized for IBS[9]. An epidemiological study in China demonstrated that 22.4%[10] of patients with IBS symptoms sought healthcare, but there were no detailed data revealing the predictors for healthcare-seeking behavior among patients with IBS in China.

The pathogenesis of IBS is unclear, and its diagnosis depends on Rome diagnostic criteria. However, in France, 67% of patients who met Rome II criteria underwent additional investigations to determine etiologies[9]. The therapeutic goals of IBS are to alleviate intestinal symptoms, reduce episodes, and improve quality of life. Nevertheless, many patients with IBS are dissatisfied with the efficacy of traditional treatment options and undergo frequent consultations, referrals, multiple medications, and even unnecessary abdominal or pelvic surgeries[11]. The present study aimed to provide evidence for IBS management strategies through a database analysis of patients with IBS from Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH).

Participants were consecutive patients with IBS enrolled in a gastroenterology clinic at PUMCH (a tertiary university hospital) from June 2009 to February 2016. Eligible patients were aged 18-65 years. All patients met Rome III diagnostic and subtype criteria[12], including recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least 3 d/mo in the last 3 mo associated with two or more of these features: (1) improvement with defecation; (2) onset associated with a change in the frequency of stools; and (3) onset associated with a change in the form of stools. Criteria were fulfilled in the last 3 mo with symptom onset at least 6 months before diagnosis. Patients with organic gastrointestinal diseases and metabolic diseases were excluded based on the results of routine tests for blood, urine, stool; liver, kidney, and thyroid function; measurements of carcinoembryonic antigen, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein; and abdominal ultrasound and colonoscopy in the past year. Eligible patients needed to be able to complete the questionnaires. After being informed about the study, some participating patients provided informed written consent and others provided oral consent to participate before study enrollment. This study was approved by the PUMCH Ethics Committee (S-234).

IBS symptom questionnaires were administered by well-trained investigators in face-to-face interviews. Information collected included demographic data, IBS disease course, frequency and severity of IBS symptoms, defecation-related symptoms, extra-intestinal symptoms, examination results in the past year, and psychological and sleeping status and management. Symptom score for IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D) was calculated according to Zhu et al[3], with a total possible score of 15 that reflected the frequency and severity of abdominal pain/discomfort, frequency of bowel movements during symptom onset, and improvement of abdominal pain/discomfort with defecation. We defined mild symptoms as a symptom score ≤ 8, moderate symptoms as 9-10, and severe symptoms as > 10, based on symptom score percentiles and the severity and frequency of abdominal pain, number of other symptoms, health-related quality of life, and healthcare use[13]. In this questionnaire, ordinary abdominal pain/discomfort referred to abdominal pain/discomfort during non-defecation, whereas persistent symptoms referred to having IBS symptom onset every day.

Patients with difficulty falling asleep, light sleep/dreaminess, sleeping time < 6 h, or early awakening in the past 3 mo were defined as having sleeping disorders. The Hamilton anxiety (HAMA) and Hamilton depression (HAMD) scales were used to evaluate patients’ psychological status by specially trained professionals through conversation and observation[14].

The validated simplified Chinese version of the IBS-Quality of Life (IBS-QOL) instrument was completed by patients and transformed to scores according to the instructions provided[3,15]. Healthcare-seeking conditions consisted of healthcare-seeking behavior throughout the whole disease course and the past year, medical costs, treatment efficacy evaluation, and satisfaction with medical care as reported by patients. Medical costs were converted and presented as USD, based on the average exchange rate during 2009-2015 from the National Bureau of Statistics of China (USD1 = CNY6.4195).

All analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0 (IBM Corporation, Somers, NY, United States). Parametric data were presented as mean ± SD. Nonparametric data were presented as median (interquartile range). Comparisons among the two groups were made by Student’s t-tests for parametric data. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare nonparametric data between the two groups. Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables. Spearman’s test was performed to assess nonparametric correlations between two quantitative variables. Univariate associations were identified by χ2 tests. Variables that were significant in the chi-square tests were included in a multivariate logistic regression model to identify independent predictors for healthcare-seeking behavior among patients with IBS. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data for 516 patients with IBS were included in the final analysis. Patients’ average age was 43.2 ± 11.8 years, and the sample included 56.8% males and 43.2% females. The median IBS disease course was 6.5 (8) years; 30.8% of patients had a disease course ≥ 10 years, and 12.0% ≥ 20 years.

IBS-D, IBS with constipation (IBS-C) and mixed IBS (IBS-M) accounted for 94.4%, 3.5%, and 2.1% of patients, respectively. We did not include patients with unsubtyped IBS. The average symptom score for IBS-D was 9.4 ± 1.6; 26.2% had mild symptoms, 51.7% moderate symptoms, and 22.1% severe symptoms. In addition, 58.1% of patients had coexisting sleeping disorders, with a median duration of 3.5 (9) years. A total of 362 patients (70.2%) completed HAMA and HAMD assessment. The average HAMA score was 16.2 ± 7.3 and the average HAMD score was 13.2 ± 6.1. We found that 62.1% of patients had coexisting anxiety, of which 49.6% were moderate to severe. In addition, 29% of patients had coexisting depression, with 14.2% being moderate to severe. The average IBS-QOL score was 71.7 ± 17.9, and there was no significant difference between males and females (73.0 ± 17.7 vs 71.0 ± 19.1, P = 0.22).

During the whole disease course, 285 patients (55.2%) had sought healthcare at least once for IBS symptoms (current consultation not included). These patients were defined as the consulter group. In the past year this figure increased to 79.3%, with an average number of visits of 4.5 ± 6.2. The majority of patients (79.3%) consulted with tertiary hospitals; primary/secondary care accounted for 20.7% of consultations. In addition, most patients (97.9%) consulted with gastroenterologists; 8.6% also consulted with other departments including general physicians (9.5%), traditional Chinese medicine practitioners (6.8%), and gynecologists (4.6%).

In the past year, 49.1% of patients had more than three consultations. Patients with anxiety and depression underwent more consultations than patients without [anxiety, 3.0 (3.5) vs 2.0 (2.8), P = 0.005; depression, 3.0 (4.0) vs 2.0 (2.9), P = 0.001]. The number of consultations for patients with IBS in the past year was positively correlated with symptom score (r = 0.271, P < 0.001) but negatively correlated with IBS-QOL score (r = -0.228, P < 0.001).

Colonoscopies: During the whole disease course, 41.9% of patients underwent colonoscopies (average 1.7 ± 1.3); 76 patients (14.7%) underwent at least two colonoscopies, with the maximum being 10 (over 6 years). In the past year, 64.9% of patients underwent colonoscopies (average 1.1 ± 0.3); 19 patients (3.7%) had colonoscopies at least twice (maximum of three).

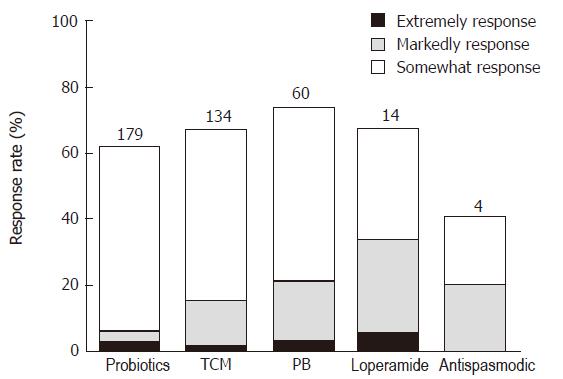

Medications and efficacy: In total, 89% of patients with IBS had taken medications during the whole disease course, with 54.7% reporting intermittent use and 16.9% long-term use. Consulters were more likely to take medications than non-consulters (93.7% vs 83.1%, P < 0.001). In the past year, the rate of medication was 88.8% and 14.8% of patients took more than three kinds of medications. Common medications used by patients with IBS-D were probiotics, traditional Chinese medicines, pinaverium bromide, loperamide, and traditional antispasmodics. Probiotics were most commonly used (52.2%), followed by traditional Chinese medicine (41.3%) (Table 1). Patient-reported medication response rates in the past year were over 50%. Although the overall response rate for pinaverium bromide was 73.1% and probiotics was 61.2%, “somewhat response” for the two medications was reported by 52.4% and 55.9%, respectively (Figure 1). Common medications used by those with IBS-C included traditional Chinese medicine, enemas, and prokinetics.

| Medications | The whole disease course | The past year |

| Probiotics | 240 (49.3) | 254 (52.2) |

| Traditional Chinese Medicine | 195 (40.0) | 201 (41.3) |

| Pinaverium bromide | 49 (10.1) | 82 (16.8) |

| Loperamide | 19 (3.9) | 21 (4.3) |

| Traditional antispasmodic | 11 (2.3) | 10 (2.1) |

Total direct medical costs estimated per patient per year for the whole disease course and for the past year were USD691.8 ± 1067.2 and USD762.7 ± 1146.0, respectively, with a maximum amount of USD7788.8. Degree of satisfaction with medical care was reported as complete satisfaction for 11.4% of patients, satisfaction for 31.8%, and dissatisfaction for 56.8%. Non-consulters reported a higher overall satisfaction rate (including complete satisfaction and satisfaction) than consulters (58.9% vs 30.5%, P < 0.001).

Univariate analysis: We investigated predictors for consultation, frequent consultations (≥ 3 times/year), frequent colonoscopies (≥ 2 times/year), long-term medications, multiple medications (≥ 3 kinds), and dissatisfaction with medical care in the whole disease course and the past year. Consulters were more likely to present with ordinary abdominal pain/discomfort, persistent symptoms, anxiety, and depression in the whole disease course. In the past year, consulters were more likely to have loose stools (Bristol Stool Form Scale type 6) and weight loss (Table 2). In addition, among frequent consulters over the whole disease course, the percentages of females, severe symptoms, weight loss, and coexisting functional dyspepsia (FD) were higher than among patients with < 3 consultations/year. In the past year, variables influencing healthcare-seeking behavior included severe symptoms, ordinary abdominal pain/discomfort, persistent symptoms, weight loss, and FD (Table 3). During the whole disease course, more females than males reported frequent colonoscopies (52.6% vs 38.6%, P = 0.047), sensation of incomplete evacuation (84.2% vs 65%, P = 0.003), and coexisting pain in other parts of the body (50% vs 33.6%, P = 0.018).

| Consulters | Non-consulters | OR (95%CI) | |

| During the whole disease course | n = 285 | n = 231 | |

| Ordinary abdominal pain/discomfort | 174 (61.1) | 101 (43.7) | 2.02 (1.43-2.92) |

| Persistent symptoms | 104 (36.5) | 60 (26.0) | 1.64 (1.12-2.40) |

| Disease course ≥ 7 yr | 121 (42.5) | 77 (33.3) | 1.48 (1.03-2.12) |

| Co-existed with GERD | 157 (55.1) | 107 (46.3) | 1.42 (1.00-2.01) |

| Sleeping disorder | 179 (62.8) | 121 (52.4) | 1.54 (1.08-2.18) |

| Anxiety1 | 128 (67.4) | 98 (57.0) | 1.56 (1.02-2.38) |

| Depression1 | 64 (33.7) | 41 (23.8) | 1.62 (1.02-2.58) |

| In the past year | n = 409 | n = 107 | |

| Mental labor | 199 (48.7) | 33 (30.8) | 2.13 (1.35-3.35) |

| Severe abdominal pain | 68 (16.6) | 27 (25.2) | 0.59 (0.36-0.98) |

| Loose stool | 312 (83.6) | 70 (72.9) | 1.70 (1.07-2.69) |

| Weight loss | 119 (29.1) | 17 (15.9) | 2.17 (1.24-3.81) |

| Frequent consulters | Infrequent consulters | OR (95%CI) | |

| During the whole disease course | n = 136 | n = 149 | |

| Female | 76 (55.9) | 65 (43.6) | 0.55 (0.35-0.86) |

| Severe symptoms | 39 (28.7) | 24 (16.1) | 1.93 (1.08-3.45) |

| Weight loss | 45 (33.1) | 26 (17.4) | 2.34 (1.35-4.07) |

| Co-existed with FD | 94 (69.1) | 79 (53) | 1.98 (1.22-3.22) |

| In the past year | n = 201 | n = 208 | |

| Severe symptoms | 62 (30.8) | 24 (11.5) | 3.42 (2.03-5.75) |

| Ordinary abdominal pain/discomfort | 123 (61.2) | 97 (46.6) | 1.8 (1.22-2.67) |

| Persistent symptoms | 80 (39.8) | 48 (23.1) | 2.20 (1.44-3.38) |

| Weight loss | 71 (35.3) | 48 (23.1) | 1.82 (1.18-2.81) |

| Co-existed with FD | 131 (65.2) | 114 (54.8) | 1.54 (1.04-2.30) |

Table 4 lists differences between patients with long-term medications and intermittent medications, multiple medications (≥ 3 kinds) and fewer than three kinds of medications. Patients with persistent symptoms, weight loss, and anxiety were more likely to take long-term and multiple medications.

| Long-term medication(n = 88) | Intermittent medication (n = 370) | OR (95%CI) | Medications ≥ 3 kinds (n = 68) | Medications < 3 kinds (n = 390) | OR (95%CI) | |

| Mental labor | 26 (29.5) | 169 (45.7) | 0.59 (0.30-0.82) | |||

| Severe symptoms | 33 (37.5) | 73 (19.7) | 2.44 (1.48-4.03) | |||

| Persistent symptoms | 45 (51.1) | 107 (28.9) | 2.57 (1.60-4.13) | 33 (48.5) | 119 (30.5) | 2.15 (1.27-3.62) |

| Weight loss | 40 (45.5) | 86 (23.2) | 2.75 (1.70-4.47) | 28 (41.2) | 98 (25.1) | 2.09 (1.22-3.56) |

| Anxiety1 | 46 (79.3) | 163 (61.3) | 2.42 (1.23-4.79) | 40 (78.4) | 169 (61.9) | 1.87 (1.11-3.15) |

| Depression1 | 24 (41.4) | 75 (28.2) | 1.80 (1.00-3.23) | |||

| Co-exist with FD | 49 (72.1) | 232 (59.5) | 1.76 (1.00-3.10) |

Comparison of degree of satisfaction with medical care in the whole disease course and in the past year showed that IBS symptoms, weight loss, sleeping disorders, and psychological disorders influenced patient-reported satisfaction rates (Table 5).

| Satisfaction | Dissatisfaction | OR (95%CI) | |

| During the whole disease course | n = 293 | n = 223 | |

| Severe symptoms | 76 (25.9) | 38 (17.0) | 1.71 (1.10-2.64) |

| Ordinary abdominal pain/discomfort | 179 (61.1) | 96 (43.0) | 2.08 (1.46-2.96) |

| Persistent symptoms | 112 (38.2) | 52 (23.3) | 2.04 (1.38-3.01) |

| Mucous stool | 196 (66.9) | 129 (57.8) | 1.47 (1.03-2.11) |

| Weight loss | 90 (30.7) | 46 (20.6) | 1.71 (1.13-2.57) |

| Co-existed with GERD | 162 (55.3) | 102 (45.7) | 1.47 (1.03-2.08) |

| Co-existed with sleeping disorder | 189 (64.5) | 111 (49.8) | 1.83 (1.29-2.62) |

| Anxiety1 | 145 (72.5) | 81 (50.0) | 2.64 (1.70-4.08) |

| Depression1 | 73 (36.5) | 32 (19.8) | 2.34 (1.44-3.78) |

| In the past year | n = 255 | n = 261 | |

| Severe symptoms | 69 (27.1) | 45 (17.2) | 1.69 (1.11-2.58) |

| Ordinary abdominal pain/discomfort | 155 (60.8) | 120 (46.0) | 1.66 (1.17-2.34) |

| Persistent symptoms | 98 (38.4) | 66 (25.3) | 1.73 (1.19-2.52) |

| Mucous stool | 172 (67.5) | 153 (58.6) | 1.46 (1.02-2.10) |

| Weight loss | 81 (31.8) | 55 (21.1) | 1.65 (1.11-2.45) |

| Anxiety1 | 125 (72.7) | 101 (53.2) | 2.34 (1.51-3.64) |

| Depression1 | 61 (35.5) | 44 (23.2) | 1.82 (1.15-2.89) |

Multivariate analysis: We entered the above influencing factors into a multivariate logistic regression model, and found ordinary (not pre-defecation) abdominal pain/discomfort was an independent predictor for consultation in the whole disease course. Severe symptoms and persistent symptoms were independent predictors for frequent consultations in the past year. In the whole disease course, frequent colonoscopies were associated with sensation of incomplete evacuation. In the past year, long-term medications were associated with persistent symptoms and weight loss. In the whole disease course, coexisting anxiety was the strongest independent predictor for dissatisfaction with medical care (Table 6).

| Adjusted OR (95%CI) | |

| Consultation in the whole disease course | |

| Ordinary abdominal pain/discomfort | 2.07 (1.31-3.27) |

| Consultation in the past year | |

| Mental labor | 2.19 (1.35-3.55) |

| Weight loss | 2.17 (1.22-3.89) |

| Frequent consultations in the whole disease course | |

| Severe symptoms | 1.88 (1.12-3.15) |

| Weight loss | 1.94 (1.09-3.47) |

| Frequent consultations in the past year | |

| Severe symptoms | 1.74 (1.06-2.82) |

| Persistent symptoms | 1.66 (1.01-2.72) |

| Frequent colonoscopies in the whole disease course | |

| Sensation of incomplete evacuation | 2.76 (1.35-5.67) |

| Co-existed pain in other parts of the body | 1.92 (1.07-3.45) |

| Long-term medication in the past year | |

| Persistent symptoms | 2.02 (1.07-3.81) |

| Weight loss | 2.58 (1.38-4.82) |

| Dissatisfaction with medical care in the whole disease course | |

| Ordinary abdominal pain/discomfort | 1.99 (1.24-3.18) |

| Weight loss | 1.73 (1.01-2.95) |

| Anxiety | 2.08 (1.20-3.59) |

In the present study, we analyzed clinical medical care data for patients with IBS from a tertiary hospital, and found that IBS-D was most common in China. Most patients consulted with gastroenterologists in tertiary hospitals, and there was a high rate of colonoscopies. In patients with IBS-D, the most commonly used medications were probiotics. Conventional treatments were reported as partially effective, and patient-reported satisfaction rates were low. Ordinary abdominal pain/discomfort, severe and persistent symptoms, weight loss, and anxiety were independent predictors for healthcare-seeking behavior and satisfaction with medical care.

In our study, patients with IBS showed a long disease course, with 30% of patients having IBS for more than 10 years, which highlighted the importance of accurate diagnosis and effective management[16]. Most of our participants had IBS-D, with 5.5% having IBS-C/IBS-M; these rates are much lower than domestic epidemiological data[10]. This might be attributed to the fact that we enrolled patients with typical IBS symptoms, and suggests patients with IBS-D might be more likely to seek healthcare. In the whole disease course, the consultation rate for IBS symptoms (55.2%) was similar to that in Taiwan (47%)[17] and the United States (46%)[18], but was lower than in Australia (73%)[18]. Chinese patients with IBS mostly consulted with tertiary hospitals (78.9%) and gastroenterologists (97.9%), which differs from Western countries[9,19] and may be related to a lack of well-established referral systems. A small number of patients consulted with other departments because of coexisting headache and urogenital symptoms[20].

The Rome III IBS diagnostic criteria emphasize improvement of abdominal pain/discomfort after defecation. However, our data showed more than half of participating patients presented with ordinary abdominal pain/discomfort (non-defecation). In addition, ordinary abdominal pain/discomfort was an independent predictor for healthcare seeking among patients with IBS. Previous published papers indicated the severity[7,16,21], frequency[21], and duration[7] of abdominal pain were predictors for seeking healthcare among patients with IBS. We demonstrated that the number of visits was positively correlated with intestinal symptom scores, and patients with severe symptoms and weight loss were more likely to frequently seek healthcare. In the past year, predictors for frequent consultations included persistent symptoms. Weight loss was one of the alarm features for patients with IBS[22] with a reported prevalence of 21%, which might be associated with FD (especially postprandial distress syndrome[23] and psychological disorders[24]). The reported prevalence of gastrointestinal malignancies in the population with unintentional weight loss was 6%-38%[25]. Patients with IBS were more worried about having serious diseases than healthy controls[26], and 21% of healthcare seekers reported “fear that abdominal symptoms relate to cancer or other illness” as the most important reason for seeking healthcare[27]. Usually, patients attributed their symptoms to organic etiologies such as intestinal infection or ulcers[28]. Fear of organic diseases prompted frequent consultations[29].

A previous study in Hong Kong[30] showed a higher degree of anxiety was an independent factor associated with healthcare-seeking behavior in IBS, but that study did not show the exact degree of anxiety and odds ratios. Despite intestinal symptoms, we found patients with anxiety and depression had more visits. During the whole disease course, anxiety and depression were more common among consulters than non-consulters. However, multifactor analysis indicated that anxiety and depression were not independent predictors for healthcare-seeking behavior.

Before study enrollment, 64.9% of patients underwent colonoscopies and 14.7% of patients had colonoscopies at least twice. In an American cohort study, the detection rate of structural lesions of the colon in non-IBS-C patients fulfilling Rome II criteria without alarm features was similar to healthy controls[31]. Akhtar et al. reviewed medical records of patients with IBS who underwent colonoscopies because of new gastrointestinal symptoms 15 years after diagnosis, and found that there was no difference in the prevalence of organic colonic lesions with non-IBS controls[32]. The newly established Rome IV criteria recommend appropriate diagnostic testing only if alarm symptoms are present[13]. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends colonoscopy should be performed in patients with IBS who have alarm features and in those aged over 50 years[22]. In China, the high colonoscopy rate may be associated with the increasing incidence of colorectal cancer[33] and the relatively low cost of examination. We demonstrated that the sensation of incomplete evacuation and pain in other parts of the body were independent predictors for frequent colonoscopies.

In total, 88% of patients had taken medications in the past year, and 14.8% had taken more than three kinds of medications. Probiotics were the most commonly used drugs. Despite multiple studies confirming the efficacy of probiotics in treating IBS[34,35], our results displayed a markedly low response rate and they are not the most commonly used drugs in Western countries. Most other investigated drugs were partially effective, which was similar to a study in the United States that showed only 19%, 18%, 15%, and 10% of patients with IBS reported medical therapy was completely effective in relieving constipation, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and bloating, respectively[11]. Psychological evaluations at enrollment showed a high prevalence of anxiety and depression, although few patients reported use of antidepressants or psychotherapy. Interestingly, 83.1% of non-consulters had taken medications, which might partially account for the low response rate. In the past year, patients with persistent symptoms and weight loss were more likely to take long-term medications.

IBS severely influenced patients’ quality of life and caused considerable financial burden. In Germany[36], total costs for IBS were €994.97 per patient per year, 37% of which was for medications; in the past year, one in 15 patients was hospitalized for IBS. In the present study, average direct costs were estimated at USD762.7 per patient in the past year. Even so, the patient-reported rate of complete satisfaction was 11.4%, which was close to United States data (14%)[11] and indicates dissatisfaction with current treatment is a global issue. In addition, 41.1% of non-consulters reported dissatisfaction with medical care, which suggests they were unsatisfied with over-the-counter drugs. Coexisting anxiety was the strongest predictor for poor satisfaction with medical care, followed by ordinary abdominal pain/discomfort. The latter suggests that the pathogenesis of ordinary abdominal pain/discomfort differs from pre-defecation abdominal pain/discomfort, and may need higher level treatment (e.g., centrally acting drugs).

There were some limitations in this study. First, we set strict inclusion criteria for patients with IBS, which excluded patients with light, atypical symptoms, and fewer examinations. In addition, some patients did not complete HAMA and HAMD evaluations. Patient-reported healthcare-seeking behavior was retrospective and we did not know whether their medications were prescription or over-the-counter medicines. Finally, our study was a single-center study and might not be representative of the overall situation in China.

In conclusion, Chinese patients with IBS were dominated by those with IBS-D. Patients most commonly consulted with tertiary hospitals and gastroenterologists, and there was a high rate of colonoscopies. Most conventional treatments were only partially effective and patients reported low satisfaction rates. Intestinal symptoms influenced healthcare-seeking behavior among patients with IBS from different levels, and coexisting anxiety was the strongest predictor for dissatisfaction with medical care.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic recurrent functional bowel disorder which impairs patients’ quality of life. Patients with IBS report poor treatment response and satisfaction rates for traditional treatments and undergo frequent consultations and referrals. In China, data for predictors of healthcare-seeking behavior and satisfaction with medical care are lacking. Studies regarding predictors for healthcare-seeking behavior among patients with IBS may provide evidence for IBS management strategies in this region.

The present study comprehensively summarized the characteristics of healthcare-seeking behavior, medical costs, and satisfaction with care among Chinese patients with IBS. The authors also investigated predictors for frequent consultations, frequent colonoscopies, dissatisfaction with medical care, and long-term and multiple medications among Chinese patients with IBS. The authors’ study provides a basis for future studies on healthcare-seeking behavior among patients with IBS, and may provide management guidance for clinicians.

The main objectives of this study were to investigate the characteristics of healthcare-seeking behavior, medical costs, and satisfaction with care among Chinese patients with IBS, and determine predictors for frequent consultations, frequent colonoscopies, dissatisfaction with medical care, and long-term and multiple medications in this population.

The authors enrolled patients with IBS who met Rome III diagnostic criteria and excluded organic diseases in a tertiary gastroenterology clinic from 2009 to 2016. Patients were administered IBS questionnaires in face-to-face interviews, which included intestinal and extra-intestinal symptoms, medical consultations and management. Data were collected and analyzed with SPSS version 19.0 software. Patients were divided into frequent consulters and infrequent consulters; frequent colonoscopies and infrequent colonoscopies; long-term medications and intermittent medications; medications ≥ 3 kinds and medications < 3 kinds; satisfaction with medical care and dissatisfaction with medical care. Univariate analysis was conducted with χ2 test to detect factors with significant differences between groups and the significant different factors above were entered into a multivariate logistic regression model to determine independent predictors for their healthcare-seeking behavior.

The authors found Chinese IBS patient present high rates of frequent healthcare- seeking behavior, colonoscopies, medications and low satisfaction with medical care. Abdominal pain/discomfort during non-defecation period (ordinary abdominal pain/discomfort) instead of pre-defecation abdominal pain/discomfort was the independent predictor for their healthcare-seeking behavior. Sensation of incomplete evacuation was the independent predictor for frequent colonoscopies. Patients with anxiety were more likely to report “dissatisfaction to medical care”. In the past year, patients with severe and persistent IBS symptoms sought medical care frequently. How to educate patients and obtain reasonable utilization of medical resources need to be solved.

The results demonstrated that most patients with IBS were partially responsive to traditional treatment. Intestinal symptoms were major predictors for healthcare-seeking behavior, and patients with anxiety were more likely to be dissatisfied with medical care. The authors’ results provided guidance for Chinese IBS management. Doctors should pay attention to patients with specific symptoms such as ordinary abdominal pain/discomfort and anxiety.

From the study, The authors learned that patients with IBS tended to undergo frequent consultations and investigations. Physicians should give patients sufficient explanations and pay attention to their psychological status. Future researches might emphasize the reasons of low effective rate of routine treatments and investigate the efficacy of psychological treatment through prospective studies.

The authors thank Shaomei Han from Department of Epidemiology and Statistics, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and School of Basic Medicine, Peking Union Medical College for her statistical support.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chiba T, Ducrotte P, Dumitrascu DL, Rodrigo L S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:712-721.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1251] [Cited by in RCA: 1416] [Article Influence: 108.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Zhang L, Duan L, Liu Y, Leng Y, Zhang H, Liu Z, Wang K. [A meta-analysis of the prevalence and risk factors of irritable bowel syndrome in Chinese community]. Zhonghua Neike Zazhi. 2014;53:969-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zhu L, Huang D, Shi L, Liang L, Xu T, Chang M, Chen W, Wu D, Zhang F, Fang X. Intestinal symptoms and psychological factors jointly affect quality of life of patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Everhart JE, Ruhl CE. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States part II: lower gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:741-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Jung HK, Kim YH, Park JY, Jang BH, Park SY, Nam MH, Choi MG. Estimating the burden of irritable bowel syndrome: analysis of a nationwide korean database. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;20:242-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhang F, Xiang W, Li CY, Li SC. Economic burden of irritable bowel syndrome in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:10450-10460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Talley NJ, Boyce PM, Jones M. Predictors of health care seeking for irritable bowel syndrome: a population based study. Gut. 1997;41:394-398. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Boyce PM. Predictors of health care seeking for irritable bowel syndrome and nonulcer dyspepsia: a critical review of the literature on symptom and psychosocial factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1340-1349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dapoigny M, Bellanger J, Bonaz B, Bruley des Varannes S, Bueno L, Coffin B, Ducrotté P, Flourié B, Lémann M, Lepicard A. Irritable bowel syndrome in France: a common, debilitating and costly disorder. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:995-1001. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Xiong LS, Chen MH, Chen HX, Xu AG, Wang WA, Hu PJ. [A population-based epidemiologic study of irritable bowel syndrome in Guangdong province]. Zhonghua Yixue Zazhi. 2004;84:278-281. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Hulisz D. The burden of illness of irritable bowel syndrome: current challenges and hope for the future. J Manag Care Pharm. 2004;10:299-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480-1491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3413] [Cited by in RCA: 3383] [Article Influence: 178.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Drossman DA. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1366] [Cited by in RCA: 1391] [Article Influence: 154.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56-62. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Huang D, Liang L, Fang X, Xin H, Zhu L, Shi L, Yao F, Sun X, Zhang F, Ke M. Effect of psychological factors on quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Zhongguo Xiaohua Zazhi. 2015;9:599-605. |

| 16. | Kwan AC, Hu WH, Chan YK, Yeung YW, Lai TS, Yuen H. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in Hong Kong. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:1180-1186. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Lu CL, Chen CY, Lang HC, Luo JC, Wang SS, Chang FY, Lee SD. Current patterns of irritable bowel syndrome in Taiwan: the Rome II questionnaire on a Chinese population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:1159-1169. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Ron Y. Irritable bowel syndrome: epidemiology and diagnosis. Isr Med Assoc J. 2003;5:201-202. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Wilson S, Roberts L, Roalfe A, Bridge P, Singh S. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome: a community survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:495-502. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Song J, Wang Q, Wang C. Symptom features of irritable bowel syndrome complicated with depression. Zhongguo Xiaohua Zazhi. 2015;35:590-594. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Huskic SS, Boyce PM. Predictors of conventional and alternative health care seeking for irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:841-851. [PubMed] |

| 22. | American College of Gastroenterology Task Force on Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Schiller LR, Schoenfeld PS, Spiegel BM, Talley NJ, Quigley EM. An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104 Suppl 1:S1-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Bilbao-Garay J, Barba R, Losa-García JE, Martín H, García de Casasola G, Castilla V, González-Anglada I, Espinosa A, Guijarro C. Assessing clinical probability of organic disease in patients with involuntary weight loss: a simple score. Eur J Intern Med. 2002;13:240-245. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Eslick GD, Howell SC, Talley NJ. Dysmotility Symptoms Are Independently Associated With Weight Change: A Population-based Study of Australian Adults. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;21:603-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Abu-Freha N, Lior Y, Shoher S, Novack V, Fich A, Rosenthal A, Etzion O. The yield of endoscopic investigation for unintentional weight loss. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:602-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Faresjö Å, Grodzinsky E, Hallert C, Timpka T. Patients with irritable bowel syndrome are more burdened by co-morbidity and worry about serious diseases than healthy controls--eight years follow-up of IBS patients in primary care. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Williams RE, Black CL, Kim HY, Andrews EB, Mangel AW, Buda JJ, Cook SF. Determinants of healthcare-seeking behaviour among subjects with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1667-1675. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Björkman I, Simrén M, Ringström G, Jakobsson Ung E. Patients’ experiences of healthcare encounters in severe irritable bowel syndrome: an analysis based on narrative and feminist theory. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25:2967-2978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gralnek IM. Health care utilization and economic issues in irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Surg Suppl. 1998;73-76. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Hu WH, Wong WM, Lam CL, Lam KF, Hui WM, Lai KC, Xia HX, Lam SK, Wong BC. Anxiety but not depression determines health care-seeking behaviour in Chinese patients with dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:2081-2088. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Chey WD, Nojkov B, Rubenstein JH, Dobhan RR, Greenson JK, Cash BD. The yield of colonoscopy in patients with non-constipated irritable bowel syndrome: results from a prospective, controlled US trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:859-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Akhtar AJ, Shaheen MA, Zha J. Organic colonic lesions in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Med Sci Monit. 2006;12:CR363-CR367. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Chen W, Zheng R, Zeng H, Zhang S. The incidence and mortality of major cancers in China, 2012. Chin J Cancer. 2016;35:73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Didari T, Mozaffari S, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. Effectiveness of probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: Updated systematic review with meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:3072-3084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 35. | Hungin AP, Mulligan C, Pot B, Whorwell P, Agréus L, Fracasso P, Lionis C, Mendive J, Philippart de Foy JM, Rubin G. Systematic review: probiotics in the management of lower gastrointestinal symptoms in clinical practice -- an evidence-based international guide. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:864-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Müller-Lissner SA, Pirk O. Irritable bowel syndrome in Germany. A cost of illness study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:1325-1329. [PubMed] |