Published online Aug 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i32.5836

Peer-review started: June 8, 2017

First decision: June 22, 2017

Revised: June 29, 2017

Accepted: July 12, 2017

Article in press: July 12, 2017

Published online: August 28, 2017

Processing time: 81 Days and 7.2 Hours

Clinical manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are not locally restricted to the gastrointestinal tract, and a significant portion of patients have involvement of other organs and systems. The visual system is one of the most frequently affected, mainly by inflammatory disorders such as episcleritis, uveitis and scleritis. A critical review of available literature concerning ocular involvement in IBD, as it appears in PubMed, was performed. Episcleritis, the most common ocular extraintestinal manifestation (EIM), seems to be more associated with IBD activity when compared with other ocular EIMs. In IBD patients, anterior uveitis has an insidious onset, it is longstanding and bilateral, and not related to the intestinal disease activity. Systemic steroids or immunosuppressants may be necessary in severe ocular inflammation cases, and control of the underlying bowel disease is important to prevent recurrence. Our review revealed that ocular involvement is more prevalent in Crohn’s disease than ulcerative colitis, in active IBD, mainly in the presence of other EIMs. The ophthalmic symptoms in IBD are mainly non-specific and their relevance may not be recognized by the clinician; most ophthalmic manifestations are treatable, and resolve without sequel upon prompt treatment. A collaborative clinical care team for management of IBD that includes ophthalmologists is central for improvement of quality care for these patients, and it is also cost-effective.

Core tip: Among all inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients, ophthalmic inflammatory disorders occur in 0.3% to 13.0% of cases, 1.6%-5.4% among the ulcerative colitis and 3.5%-6.8% among the Crohn’s disease patients. Since asymptomatic inflammation of ocular tissues may occur, a routine ophthalmic follow-up is recommended in all IBD patients, mainly before changes in IBD therapy because some drugs may cause ocular adverse effects. Patients with chronic or recurrent use of systemic corticosteroids should be warned of the risk of cataracts and glaucoma. Patient awareness of possible eye involvement is important in improving understanding of their disease and health outcomes, supporting early diagnosis, which will contribute to success of the treatment.

- Citation: Troncoso LL, Biancardi AL, de Moraes Jr HV, Zaltman C. Ophthalmic manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A review. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(32): 5836-5848

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i32/5836.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i32.5836

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic, immune-mediated inflammatory gastrointestinal disease of unknown etiology[1-4]. Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) are the main types of IBD, with different pathophysiology and clinical features but both characterized by episodes of recurrent acute attacks[1,4-9].

The incidence and prevalence of IBD are highly variable, depending on the population studied[8,10-12], with an estimated global prevalence of 146.9 cases/100000 people. IBD has shown progressive increases in newly industrialized countries in Asia, South America and the Middle East, and has evolved into a global disease with a rising prevalence on every continent[13]. The highest worldwide prevalence of IBD is found in Europe, with 322 and 505 cases per 100000 people for CD and UC, respectively[3,8].

IBD is a chronic disease and requires chronic treatment. In addition, the disease has a great impact on the patient’s quality of life, commonly requiring a lifetime of care. Ocular complaints can occur as an extraintestinal manifestation (EIM) of the disease or may be drug-related. These disorders can be non-specific, with no clinical relevance to the patient and/or the physician, but the risk of complications is a reality. Thus, early detection and treatment are necessary to prevent poor outcomes, as discussed in this review.

Considering the underlying disease, the prevalence of EIM is variable and ranges between 12% to 35% in UC and 25% to 70% in CD[2,14-16]. Indeed, 6%-40% of patients with IBD have one or more EIMs that can be more debilitating than the underlying IBD itself[17]. Although the EIMs have a multifactorial pathogenesis, it is not well understood[16]. It seems to be related to an immune response against toxins and antigens that reach the bloodstream from the gastrointestinal tract, leading to an antigen-antibody complex deposition in different extraintestinal tissues[2,18-21].

Other complex mechanisms are speculated in some cases. It has been suggested that a human epithelial colonic autoantigen that is also present in the skin, bile ducts, eyes and joints triggers an antibody-mediated immune response[5,22,23] and that this is related to intestinal and extraintestinal symptoms in UC patients, but not in CD[5]. A higher incidence of HLA-B27 and HLA-DRB1*0103 positivity was demonstrated in IBD patients, and an association with extensive disease and the development of EIMs, mainly ocular and articular, has been reported[9,22,24]. However, Lanna et al[25] analyzed 96 IBD patients and found no association between HLA positivity and ocular or joint manifestations, suggesting that this finding could be justified by the great genetic heterogeneity in different global populations.

The frequency of EIMs in each type of IBD patient is controversial. Most studies show a higher frequency of EIMs in CD patients[2,20,26-28], while some report similar frequencies in both diseases[29]. EIMs may occur before an IBD diagnosis and even before recurrent intestinal episodes[3,30]. The diagnosis of IBD in those under 40 years old and of female sex are considered risk factors for the development of EIMs[2,31].

Among EIMs, musculoskeletal conditions are most common, followed by mucocutaneous and ophthalmic diseases[15,32]. However, nearly any organ, including those of dermatologic, hepatopancreatobiliary, renal, pulmonary and endocrinological systems, can be involved, leading to a significant challenge to physicians who manage IBD patients[2,15,19]. Most IBD patients with EIMs have active colonic inflammation; although, they can occur prior to, or after, the onset of colonic symptoms[20,26,33-35]. Early recognition of EIMs is important as they may characterize subclinical inflammation in IBD patients, with a possible increased risk of morbidity and mortality[19,35,36].

The aim of this review was to evaluate the current literature about ocular EIMs, emphasizing inflammatory alterations that need prompt recognition to avoid irreversible visual impairment. Reference lists from the articles selected by electronic searching were manually reviewed to identify further relevant studies. Articles in each of these multiple searches were reviewed, and those meeting the inclusion criteria, that is, publications providing data on the incidence, prevalence, clinical features and management of ophthalmologic manifestations in IBD, were recorded.

The ocular system can be affected by several immune systemic diseases, including IBD[29,37-42]. Crohn[42] published the first report of ocular involvement in IBD in 1925, in which it was suggested that two patients he treated probably suffered from keratomalacia and xerophthalmia.

Since the first report, the main ocular findings have been related to inflammatory manifestations[20,25,27,29,43-45] that occur in the early years after an IBD diagnosis[2,15]. Although these findings can indicate disease activity[15,18], the association with the gastrointestinal tract-affected area is not well established[2,15]. It has been demonstrated that there is a greater tendency of ocular inflammation in CD patients, mainly with colitis or ileocolitis, and UC patients with pancolitis[2,34,46]. Zippi et al[28] corroborate the literature data in their retrospective study in Italian IBD patients, demonstrating a significant association between ocular EIM and CD.

The prevalence of ophthalmic inflammatory disorders is variable, according to the population studied, ranging from 0.3% to 13.0% among all IBD patients[14,20,25,27,29,34,45,47], 1.6%-5.4% among those with UC and 3.5%-6.8% among those with CD[25,29]. Although a greater frequency of ocular involvement has been demonstrated in CD vs UC patients[23,48], the results are controversial[25,27].

Considering the risk factors for developing ocular manifestation in IBD, an association has been reported with female sex[17,23,31], and the presence of arthritis or arthralgia in CD patients[23,46]. A paradoxical positive association has been demonstrated between smoking and ocular manifestation in UC patients[49], because it is well known that smoking exerts a protective effect against both the development and progression of UC[50,51].

The physiopathology of ocular EIMs remains unclear[2,25,29,52-54]. It has been suggested that local action of antigen-antibody complexes produced against the bowel wall vessels and transported via the bloodstream could be responsible for eye involvement[18,19]. However, Santeford et al[52] suggested a disturbance in physiological macrophage-mediated autophagy as a potential molecular link between systemic disease and uveitis. Lin et al[55], in a large retrospective analysis, suggested that a family history of IBD itself may confer an independent, increased susceptibility to the development of ocular inflammation, despite the absence of bowel disease or of known genetic susceptibility (HLA-B27).

The most common ocular manifestations related to IBD are episcleritis (2%-5%) and uveitis (0.5%-3.5%)[15,17,29,32], as listed in Table 1.

| Ref. | Country | Study design | Ocular exam sample | Ocular manifestationfrequency | Comment |

| Karmiris et al[56] (2016) | Greece | Prospective cohort | 1860 (1001 CD; 859 UC) | 55 (3%) | Ocular EIMs represented the third most frequent group of EIM in the study |

| (45 CD; 10 UC): 31 Anterior uveitis (25 CD; 6 UC); 16 Episcleritis (16 CD); 7 Posterior uveitis (3 DC; 4 UC); 1 Central serous retinopathy (CD) | All patients with episcleritis suffered from CD. There were patients with anterior and posterior uveitis | ||||

| Manser et al[57] (2016) | Switzerland | 140 UC patients with EIM or complications | 22 (15.7%) Uveitis | Investigated prevalence of uveitis in patients with UC | |

| Bandyopadhyay et al[27] (2015) | India | 120 (62 CD; 58 UC) | 16 (13%)(8 CD; 8 UC): 7 Uveitis (7 CD); 9 Episcleritis (1 CD; 8 UC) | Authors describe two cases of scleritis (2 CD) and one of endophthalmitis (CD) that were not accounted as ocular manifestations. Authors consider a selection bias, as most participants had severe intestinal disease | |

| Isene et al[58] (2015) | Europe (Norway, Denmark, Netherlands, Spain, Italy, Greece, and Israel) | Prospective cohort | 1145 (364 CD; 781 UC) | 12 (1.0%)10 (0.9%) Anterior uveitis; 2 (0.2%) Episcleritis | Authors concluded that familial IBD does not predict increased risk of immune-mediated EIM, as smoking does not seem to influence the risk |

| Zippi et al[28] (2014) | Italy | Retrospective | 811 (216 CD; 595 UC) | 26 Uveitis (3.2%)(16 CD; 10 UC) | It is not informed if other ocular manifestations have been investigated in addition to uveitis. |

| Cloché et al[59] (2013) | France | 74 IBD (no underlying disease specification) | 1 (1.4%): Scleritis | A large number of patients were receiving biological agents, approximately 50%, that may treat IBD and prevent ocular inflammation. Authors do not define the underlying IBD of the scleritis patient | |

| Vavricka et al[22] (2011) | Switzerland | Prospective Cohort | 950 (580 CD; 370 UC) | 50 (5.3%)(36 CD; 14 UC): 50 Uveitis | Only uveitis was considered ocular EIM, and it was associated to active CD, but no relation was found to UC activity |

| Cury et al[60] (2010) | Brazil | 88 (48 CD; 40 UC) | 7 (6.25%)(no underlying disease specification): 1 Conjunctivitis; 3 Blepharitis; 1 Episcleritis; 2 Uveitis; 2 Cataracts | The study used a control group of 24. Considered also unspecific ocular abnormalities, as cataract and blepharitis | |

| Felekis et al[61] (2009) | Greece | Prospective cohort | 60 (23 CD; 37 UC) | 26 (43%)(12 CD; 14 UC): 13 Dry eye; 8 Glucocorticoid-induced cataract; 3 Iridociclitis; 3 Retinal pigment epithelium disturbances; 2 Episcleritis; 2 Serous retinal detachment; 1 Conjunctivitis; 1 Choroiditis; 1 Vasculitis; 1 Optic neuritis | The study used a control group of 276. Authors conclude that ocular manifestations occur in UC patients as frequently as in CD patients; however, the results of the statistical analysis are not mentioned for any of the study variables |

| Lanna et al[25] (2008) | Brazil | 96 (59 CD; 37 UC) | 6 (6.2%)(4 CD; 2 UC): 4 Uveitis (2 bilateral; 2 CD; 2 UC); 1 Scleritis (CD); 1 Episcleritis (CD) | It was not possible to analyze the association between the HLA-B27 and ocular abnormalities because only 3 of the 6 patients had been tested for HLA-B27; all of them were negative for this antigen | |

| Yilmaz et al[35] (2007) | Turkey | Prospective cohort | 116 (20 CD; 96 UC) | 28 (24.13%)(12 CD; 22 UC): 10 Conjunctivitis; 8 Blepharitis; 6 Uveitis; 6 Cataracts; 4 Episcleritis | Study considered unspecific ocular abnormalities, as cataract and blepharitis, which are very frequent in the general population |

| Mendoza et al[29] (2005) | Spain | Prospective cohort | 566 (295 CD; 271 UC) | 13 (2.3%)(6 CD; 7 UC): 8 Uveitis (2 CD; 6 UC); 5 Episcleritis (4 CD; 1 UC) | In 2 patients the ophthalmologic clinical presentation preceded the diagnosis of IBD, but its frequency is probably undervalued considering the high prevalence of asymptomatic uveitis |

| Ricart et al[47] (2004) | United States | 243 IBD [47 familial IBD (25 CD; 22 UC); 196 sporadic IBD (114 CD; 82 UC)] | Familial IBD: 3 (2 CD; 1 UC)Sporadic IBD: 10 (7 CD; 3 UC)Authors don't specify which ocular EIM was found | Significant association between EIM and disease status (familial vs sporadic) was not detected. This suggests that susceptibility genes for the development of IBD and the susceptibility genes for the development of EIM are different | |

| Lakatos et al[2] (2003) | Hungary | Prospective cohort | 873 (254 CD; 619 UC) | 28 (3.2%)(8 CD; 20 UC): 13 Conjunctivitis (4 CD; 9 UC), 10 Anterior uveitis (4 CD; 6 UC); 5 Scleritis (1 CD; 4 UC); 1 Orbital pseudotumor (female UC patient) | The prevalence was more frequent in women in both UC and CD. In UC more than half of the patients with ocular complication had pancolitis |

| Christodoulou et al[62] (2002) | Greece | Retrospective | 248 (37 CD; 215 UC) | 4 (1.61%)(1 CD; 3 UC): 4 Iridocyclitis | Evaluated only iridocyclitis as ocular EIM |

Karmiris et al[56] performed an important study due to the large number of subjects evaluated. They retrospectively analyzed 1860 (1001 with CD and 859 with UC) Greek IBD patients’ medical reports. Arthritic, mucocutaneous and ocular (3% of IBD patients; 8.9% of all EIM occurrences) were the most common types of manifestations. Ocular EIMs were more frequent in women (54.55%) and CD patients (81.82%), with the exception of posterior uveitis, which had a predominance in UC patients. The authors mentioned episcleritis as the most frequent manifestation, although 31 cases of anterior uveitis and 16 cases of episcleritis were found. Disease activity was evaluated clinically in 346 participants, according to the treating physician’s assessment (presence of symptoms associated with elevated inflammatory markers, mainly C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, despite appropriate treatment at the time of the EIM diagnosis). They found 225 (65%) active IBD and 121 (35%) quiescent cases. The relationships between ocular EIM and IBD activity and extent, or behavioral and smoking habits were not clearly mentioned in the study.

Similarly, Bandyopadhyay et al[27] reported in their study of 120 Indian IBD patients an association between general EIMs and female sex, Hindu religion, severe gastrointestinal disease and steroid usage, but did not mention specific associations with ocular EIMs. The frequency of ocular EIM reported was similar to that among American and European populations. Manser et al[57] detected uveitis in 15.7% of patients with extraintestinal complications and 12.3% of all 179 UC patients evaluated. They suggested that the introduction of early mesalazine therapy, up to 2 mo after UC diagnosis, could be a protective factor against the development of EIMs[58].

Cloché et al[59] evaluated 74 of 305 IBD patients with ophthalmological symptoms. Only one patient presented with scleritis and they concluded that ocular symptoms were neither specific nor associated with ocular inflammation. A limitation of the study was that only symptomatic patients underwent examinations. No subclinical occurrence was investigated; thus, it is not possible to determine the actual occurrence of ocular manifestations in the total sample. Even evaluating only symptomatic patients, a frequency of ocular manifestation of 1.4% was found, lower than that found in the literature. A possible explanation is based on the large number of patients receiving biological agents, about 50%, which may have treated the IBD and prevented ocular inflammation[60].

In an important prospective study, Felekis et al[61] performed complete eye examinations in 60 IBD patients, finding a high frequency of 43% of ocular EIMs. However, in some cases these findings could have been coincidental and not related to IBD, such as dry eye and blepharitis. According to the methodology, individuals with ocular symptoms were excluded from the control group, and half of the sample of IBD patients was selected during hospitalization (severe disease activity), suggesting selection bias. Even so, the article presents some ocular findings that are infrequent in the literature, because the subjects underwent complementary fundus examinations with fluorescein angiography, increasing the importance of the study.

Lanna et al[25] performed eye examinations in 96 of 130 IBD patients. Six patients (four with CD, two with UC) presented ocular manifestations. Uveitis was diagnosed in four patients, anterior nodular scleritis in a woman with CD, and episcleritis in a man with CD with recurrent peripheral arthritis and psoriasis. One of the two men with anterior uveitis also had ankylosing spondylitis.

Yilmaz et al[35] and Cury et al[60] considered all ocular findings as EIMs, including conjunctivitis, blepharitis, and cataracts. Some entities have a high prevalence in the general population, regardless of the presence of intestinal disease, what can be considered a confounding factor in the analysis. It is difficult to establish any relationship between these occurrences and IBD because they may be related to other factors, such as age and other underlying factors.

Cury et al[60] described a correlation between dry eye and the use of 5-aminosalicylates in IBD patients. Apparently, dry eye disease may be associated with IBD and also may be related to its treatment. Blepharitis was less common in IBD patients than controls (3% vs 33%)[60], suggesting a protective action of the drug used in IBD treatment.

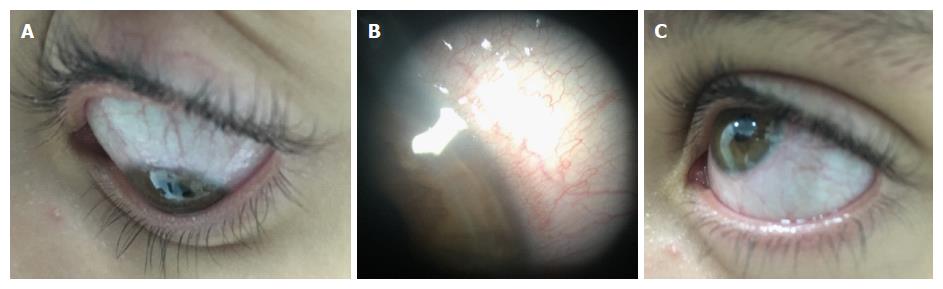

Episcleritis is a benign inflammation of the episclera, the thin blood-rich layer of tissue that covers the sclera. It is the most common ocular manifestation and causes moderate discomfort, acute redness in one or both eyes[34], and diffuse or localized episcleral edema, particularly surrounding the episcleral vessels[40]. Its classification as nodular or diffuse does not affect the prognosis[62-64].

Episcleritis seems to be more associated with IBD activity when compared with other ocular EIMs. It appears during flares of IBD, and its resolution occurs with effective treatment of the intestinal disease[20,32,41,46,54]. It is usually recurrent and can spread to the sclera, causing scleritis[40,43]. To an untrained observer and without a slit lamp examination, it is not easy to distinguish the two entities[65]. Differentiation from conjunctivitis, which is a frequent condition in the general population and may occur coincidently in patients with IBD, may also be difficult[43,66,67].

The differential diagnosis between episcleritis, uveitis, and scleritis is based on the absence of moderate-to-severe eye pain, photophobia, blurring, and low vision in the former[33]. Episcleral injection blanches with topical application of phenylephrine and softens with palpation[66]. As a benign condition, specific treatment is not always necessary; however, cool compresses, lubricant eye drops, topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and topical corticosteroids are occasionally required[20,33,34,54,66]. Figure 1 illustrates diffuse episcleritis.

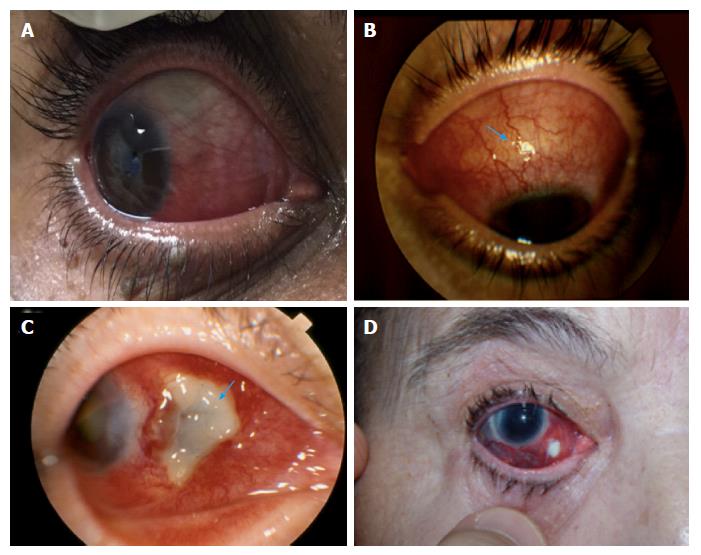

Scleritis is an inflammation of the sclera, the opaque and protective outer layer of the eye, that causes ocular pain, which radiates to the face and scalp. Characteristically, it worsens at night, and is associated with ocular hyperemia and visual loss[34,40]. It can present with a deep scleral injection that does not blanch with phenylephrine[66].

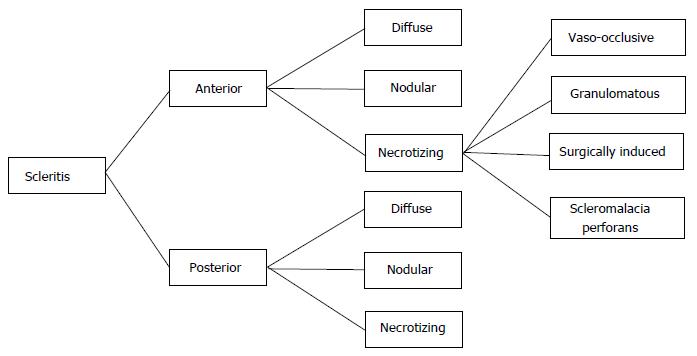

Scleritis and intermediate or posterior uveitis are much rarer than episcleritis and anterior uveitis in IBD, occurring in less than 1% of cases, but should be evaluated with caution because, if left untreated, it may progress to permanent visual loss[33]. Scleritis classification is important because it is related to severity and prognosis. Watson and Hayreh[63] classified scleritis as anterior (diffuse, nodular, or necrotizing, with or without inflammation) and posterior. Involvement of the anterior part of the sclera is more common and posterior scleritis is not associated with ocular hyperemia. A modified classification of scleritis was proposed by Watson et al[64] (Figure 2) in accordance with location (anterior or posterior), and clinical presentation (diffuse, nodular, or necrotizing). The necrotizing anterior scleritis was classified according to its etiology, as vaso-occlusive, granulomatous, surgically induced, and scleromalacia perforans. Figure 3 illustrates the different types of scleritis.

Systemic treatment is necessary in all cases, usually with oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs but they should be used with great caution in active IBD[68]. Systemic steroids or immunosuppressants may be necessary in severe cases, and control of the underlying bowel disease is important to prevent recurrence[34,68]. To avoid side effects of long-standing corticosteroids use, immunosuppressive therapy is required[40], which will be discussed regarding uveitis treatment.

Uveitis is the third leading cause of irreversible blindness in developed countries[37,52,69]. It is defined as inflammation of the uveal tract, the middle layer of the eye, which includes the iris, ciliary body, and choroid[70]. It is classified according to the primary site of inflammation as anterior, intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis[70] (Table 2).

| SUN classification | Primary site of inflammation | Manifestation |

| Anterior uveitis | Anterior chamber | Iritis, iridocyclitis, anterior cyclitis |

| Intermediate uveitis | Vitreous | Pars planitis, posterior cyclitis, hyalitis |

| Posterior uveitis | Retina or choroid | Focal, multifocal or diffuse choroiditis, chorioretinitis, retinochoroiditis, retinitis, neuroretinitis |

| Panuveitis | Anterior chamber, vitreous, and retina or choroid |

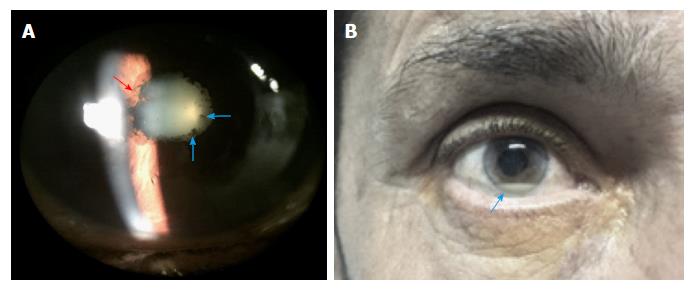

Uveitis is characterized by vascular dilation, leading to conjunctival injection, aqueous flare related to increased vascular permeability, and aqueous and vitreous inflammatory cells[69]. Uveitis can be idiopathic[38,71], drug-related[72,73], or systemic disease-related[37,38,74]; in approximately 50% of cases, an underlying disease can be identified[38]. Anterior uveitis is the most common pattern, related to seronegative spondyloarthropathies[40,55,74]. Figure 4 shows the clinical signs of anterior uveitis.

In IBD patients, anterior uveitis has an insidious onset, it is longstanding and bilateral[25,33,46,75], and not related to the intestinal disease activity[32,54,68,76]. In contrast, Vavricka et al[22], after prospectively evaluating a large sample of IBD patients, demonstrated an association between uveitis and CD activity, but not with UC.

A clinical overlap of anterior uveitis, dermatologic manifestations (erythema nodosum)[43], and musculoskeletal symptoms (arthritis and sacroileitis)[18,75,77] in CD was reported. It was proposed that a common antigen (an isoform of tropomyosin) in the non-pigmented ciliary epithelium of the eye, the keratinocytes, chondrocytes and the gut triggered an autoimmune reaction[22,23]. Thus, in IBD patients with eye complaints and others EIMs, the presence of uveitis must be considered[34,68]. Because uveitis has a variable chronicity and severity, it may be complicated, according to its primary site of inflammation, by cataracts, glaucoma, band keratopathy, hyphema, vitreous hemorrhage, cystoid macular edema, retinal detachment, retinal ischemia, optic atrophy, chronic eye pain and blindness[69].

Prompt treatment can avoid complications and visual impairment[38,40,76]. Treatment of anterior uveitis is based on topical steroids, to reduce inflammation, and topical cycloplegics, to prevent ciliary body and pupillary spasms related to ocular pain. Also, cycloplegics prevent posterior synechiae because they dilate the pupil and stabilize the blood-aqueous barrier, avoiding protein leakage (flare)[33,34,68]. According to the gravity of uveitis, periocular corticosteroid injections or systemic corticosteroids may also be necessary[37,53]. Uveitis with a chronic course requires immunosuppressive therapy to spare the prolonged use of corticosteroids and their side effects[38,53]. However, the choice of immunosuppressive therapy requires a multidisciplinary decision, especially if there is another associated EIM[20].

Cyclosporine, a T-cell inhibitor[24,32,41], thiopurines (antimetabolites)[33,41,66,78], methotrexate[33,41,79], sulfasalazine (5-ASA derivate)[68,80], and biological anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents (mainly infliximab and adalimumab)[33,81] are effective in treating both the IBD and the inflammatory IBD-related ocular impairment[6,34,44,53,82-85]. Although vedolizumab and certolizumab pegol have been introduced more recently in the therapy of CD[8,82,83], their efficacy in ocular inflammation is unknown. Despite the fact that the anti-metabolite mycophenolate can be used to treat uveitis[68,78,86,87], it is not indicated as an IBD treatment[81].

Patient awareness of EIMs is important in improving patient understanding of their disease and health outcomes[88]. It also increases the likelihood of early diagnosis, contributing to success of the applied treatment.

Other ophthalmic manifestations have been described in relation to IBD. Table 3 presents observational case reports, interventional case reports, and case series describing other ocular disorders in IBD patients. Some of these manifestations can be debilitating if not recognized and treated at an early stage.

| Ref. | Country | Ocular impairment | IBD |

| Hwang et al[89] (2001) | Canada | Dacryoadenitis | CD |

| Mochizuki et al[90] (2010) | Japan | UC | |

| Boukouvala et al[91] (2012) | United Kingdom | CD | |

| Jakobiec et al[92] (2014) | United States | 2 CD | |

| Ruiz Serrato et al[15] (2013) | Spain | Palpebral ptosis | CD |

| Diaz-Valle et al[93] (2004) | Spain | Lid margin ulcers | CD |

| Leibovitch et al[94] (2005) | Australia | Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans of eyelids | UC |

| Garrity et al[95] (2004) | United States | Orbital myositis | 2 CD |

| Verma et al[96] (2013) | Canada | CD | |

| Foroozan et al[97] (2003) | United States | Ocular miasthenia graves | UC |

| Pham et al[31] (2011) | United States | Peripheral ulcerative keratitis | 3 CD |

| Roszkowska et al[98] (2013) | Italy | Salzmann nodular corneal degeneration | CD |

| Zullow et al[99] (2017) | United States | Central serous chorioretinopathy | UC |

| Geyshis et al[100] (2013) | Israel | UC | |

| Assadsangabi et al[101] (2010) | United Kingdom | CD | |

| Ugarte et al[102] (2002) | United Kingdom | Serpiginous chorioretinopathy | CD |

| Casalino et al[103] (2014) | Italy | Choroidal neovascularization | CD |

| Thomas et al[104] (2014) | United States | CD | |

| Unal et al[105] (2008) | Turkey | CD | |

| Saatci et al[106] (2002) | Turkey | Retinal vasculitis | CD |

| Larsson et al[107] (2000) | Sweden | Retinal vein occlusion | 1 CD, 1 UC |

| Buchman et al[108] (2006) | United States | UC | |

| Unal et al[105] (2008) | Turkey | CD | |

| Yamane et al[109] (2007) | Brazil | CD | |

| Vayalambrone et al[110] (2011) | United Kingdom | UC | |

| Falavarjani et al[111] (2012) | Iran | Retinal artery occlusion | CD |

| Abdul-Rahman et al[112] (2010) | New Zealand | CD | |

| Saatci et al[106] (2002) | Turkey | CD | |

| Siqueira et al[113] (2016) | Brazil | CD | |

| Saatci et al[106] (2002) | Turkey | Retinal neovascularization | CD |

| Fuentes-Páez et al[114] (2007) | Spain | Subretinal fibrosis and uveitis syndrome | UC |

| Munk et al[115] (2016) | United States | Acute macular neuroretinopathy | UC |

| McClelland et al[116] (2012) | United States | Optic perineuritis | CD |

| Felekis et al[117] (2010) | Greece | Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy | CD |

| Mason et al[118] (2002) | United States | Macular edema | CD |

| De Franceschi et al[119] (2000) | Italy | Dystrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium | CD |

| Villain et al[120] (2002) | France | Pseudotumor cerebri | CD |

Ocular impairment may be related to IBD, drug therapy or to other factors, such as age, genetics and other concomitant diseases[34,38]. Cataracts and open-angle glaucoma are complications of long-standing ocular inflammation or the prolonged use of corticosteroids[34,37,41,43]. Some ocular manifestations have been related to drugs used in the treatment of IBD, such as corneal immune infiltrates[121] and diffuse retinopathy[122] related to adalimumab, anterior optic neuropathy[123] and retinal vein thrombosis[124,125] developing after infliximab, and cyclosporine, used in CD, causing rare optic neuropathy[66]. Levels of methotrexate in tears approximate serum levels after short-term use, which may lead to irritation of the conjunctiva, cornea, and eyelids[67].

Uveitis has been associated with the use of biological anti-TNF drugs. It has been described in association with etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, and rifabutin[72,73]. Inflammation declines with drug withdrawal, which is recommended, and the use of topical corticosteroids may be necessary to complete the remission of the inflammatory condition[38,72]. Furthermore, neurological side effects from drug therapy can cause visual impairment without directly affecting the eyes[126].

Katsanos et al[48] performed a review of orbital and optic nerve involvement in IBD. It was found that optic nerve impairment can occur as a result of damage of the optic nerve tissue per se, as a result of inflammation and/or ischemia, due to intracranial hypertension, and secondary to anti-TNF agents. In some cases, it was difficult to determine the exact cause of ocular involvement in IBD.

After bowel resection in the IBD context, short bowel and malabsorption syndromes can lead to vitamin A deficiency, which may result in night blindness (nyctalopia) and keratoconjunctivitis sicca[127,128]. Vomiting and unilateral painful red eye lead to a suspicion of acute angle closure glaucoma[67], a threatening ophthalmological urgency that has not been described in IBD but which may confound the clinician.

Finally, an association between the use of latanoprost eye drops for glaucoma treatment and IBD relapse has been reported[129]. It was concluded that the systemic absorption of the prostaglandin analog could have caused an increase in intestinal inflammation in IBD patients.

Physicians must remember that ocular involvement is more prevalent in CD and in active IBD, primarily in the presence of others EIMs. The ophthalmic symptoms in IBD are mainly non-specific and their relevance may not be recognized by the clinician. Moreover, asymptomatic inflammation of ocular tissues may occur, so a routine ophthalmic follow-up is recommended in all IBD patients (with or without ocular symptoms), mainly before changes in IBD therapy, because some drugs may cause ocular adverse effects. It is important to remember that most ophthalmic manifestations are treatable without sequel if recognized promptly.

Ophthalmologists must consider that ophthalmic manifestations of IBD may precede the systemic disease, and systematic anamnesis must be done in chronic uveitis of unknown etiology. Patients with chronic or recurrent use of systemic corticosteroids should be warned of the risk of cataracts and glaucoma. A collaborative clinical care team for management of IBD that includes ophthalmologists is central for improvement of the quality care for these patients, and is also cost-effective.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Christodoulou DK, Pan WS, Saniabadi AR, Sivandzadeh GR S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Xu XR

| 1. | Ye Y, Pang Z, Chen W, Ju S, Zhou C. The epidemiology and risk factors of inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:22529-22542. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Lakatos L, Pandur T, David G, Balogh Z, Kuronya P, Tollas A, Lakatos PL. Association of extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease in a province of western Hungary with disease phenotype: results of a 25-year follow-up study. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2300-2307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389:1756-1770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2199] [Cited by in RCA: 2489] [Article Influence: 311.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Silva FA, Rodrigues BL, Ayrizono ML, Leal RF. The Immunological Basis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:2097274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | de Souza HS, Fiocchi C. Immunopathogenesis of IBD: current state of the art. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:13-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1185] [Cited by in RCA: 1120] [Article Influence: 124.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Bosques-Padilla F, de-Paula J, Galiano MT, Ibañez P, Juliao F, Kotze PG, Rocha JL, Steinwurz F, Veitia G. Diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: First Latin American Consensus of the Pan American Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2017;82:46-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Uniken Venema WT, Voskuil MD, Dijkstra G, Weersma RK, Festen EA. The genetic background of inflammatory bowel disease: from correlation to causality. J Pathol. 2017;241:146-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel JF, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2017;389:1741-1755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1121] [Cited by in RCA: 1806] [Article Influence: 225.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (111)] |

| 9. | Ordás I, Eckmann L, Talamini M, Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2012;380:1606-1619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1151] [Cited by in RCA: 1547] [Article Influence: 119.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 10. | Malik TA. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Historical Perspective, Epidemiology, and Risk Factors. Surg Clin North Am. 2015;95:1105-1122, v. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Malekzadeh MM, Vahedi H, Gohari K, Mehdipour P, Sepanlou SG, Ebrahimi Daryani N, Zali MR, Mansour-Ghanaei F, Safaripour A, Aghazadeh R. Emerging Epidemic of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in a Middle Income Country: A Nation-wide Study from Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2016;19:2-15. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Prideaux L, Kamm MA, De Cruz PP, Chan FK, Ng SC. Inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: a systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1266-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:720-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1157] [Cited by in RCA: 1874] [Article Influence: 187.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Van Assche G, Gómez-Ulloa D, García-Álvarez L, Lara N, Black CM, Kachroo S. Systematic Review of Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonists in Extraintestinal Manifestations in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:25-36.e27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ruiz Serrato A, Marín García D, Guerrero León MA, Vallejo Herrera MJ, Villar Jiménez J, Cárdenas Lafuente F, García Ordóñez MA. [Palpebral ptosis, a rare ocular manifestation of Crohn’s disease]. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2013;88:323-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Goudet P, Dozois RR, Kelly KA, Ilstrup DM, Phillips SF. Characteristics and evolution of extraintestinal manifestations associated with ulcerative colitis after proctocolectomy. Dig Surg. 2001;18:51-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, Yu N. The prevalence of extraintestinal diseases in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1116-1122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 495] [Cited by in RCA: 510] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Karlinger K, Györke T, Makö E, Mester A, Tarján Z. The epidemiology and the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Radiol. 2000;35:154-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Das KM. Relationship of extraintestinal involvements in inflammatory bowel disease: new insights into autoimmune pathogenesis. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:1-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Evans PE, Pardi DS. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: focus on the musculoskeletal, dermatologic, and ocular manifestations. MedGenMed. 2007;9:55. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:417-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2693] [Cited by in RCA: 2747] [Article Influence: 119.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 22. | Vavricka SR, Brun L, Ballabeni P, Pittet V, Prinz Vavricka BM, Zeitz J, Rogler G, Schoepfer AM. Frequency and risk factors for extraintestinal manifestations in the Swiss inflammatory bowel disease cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:110-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 378] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Orchard TR, Chua CN, Ahmad T, Cheng H, Welsh KI, Jewell DP. Uveitis and erythema nodosum in inflammatory bowel disease: clinical features and the role of HLA genes. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:714-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Taylor SR, McCluskey P, Lightman S. The ocular manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17:538-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lanna CC, Ferrari Mde L, Rocha SL, Nascimento E, de Carvalho MA, da Cunha AS. A cross-sectional study of 130 Brazilian patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: analysis of articular and ophthalmologic manifestations. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:503-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Abbasian J, Martin TM, Patel S, Tessler HH, Goldstein DA. Immunologic and genetic markers in patients with idiopathic ocular inflammation and a family history of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154:72-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bandyopadhyay D, Bandyopadhyay S, Ghosh P, De A, Bhattacharya A, Dhali GK, Das K. Extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease: Prevalence and predictors in Indian patients. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2015;34:387-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zippi M, Corrado C, Pica R, Avallone EV, Cassieri C, De Nitto D, Paoluzi P, Vernia P. Extraintestinal manifestations in a large series of Italian inflammatory bowel disease patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17463-17467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mendoza JL, Lana R, Taxonera C, Alba C, Izquierdo S, Díaz-Rubio M. [Extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease: differences between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis]. Med Clin (Barc). 2005;125:297-300. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Tappeiner C, Dohrmann J, Spital G, Heiligenhaus A. Multifocal posterior uveitis in Crohn’s disease. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;245:457-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Pham M, Chow CC, Badawi D, Tu EY. Use of infliximab in the treatment of peripheral ulcerative keratitis in Crohn disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152:183-188.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Brazilian Study Group of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Consensus guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Arq Gastroenterol. 2010;47:313-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Harbord M, Annese V, Vavricka SR, Allez M, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Boberg KM, Burisch J, De Vos M, De Vries AM, Dick AD. The First European Evidence-based Consensus on Extra-intestinal Manifestations in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:239-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 619] [Cited by in RCA: 546] [Article Influence: 60.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Levine JS, Burakoff R. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2011;7:235-241. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Yilmaz S, Aydemir E, Maden A, Unsal B. The prevalence of ocular involvement in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:1027-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Verbraak FD, Schreinemachers MC, Tiller A, van Deventer SJ, de Smet MD. Prevalence of subclinical anterior uveitis in adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:219-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | You C, Sahawneh HF, Ma L, Kubaisi B, Schmidt A, Foster CS. A review and update on orphan drugs for the treatment of noninfectious uveitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:257-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Schwartzman S. Advancements in the management of uveitis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2016;30:304-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Thomas AS, Lin P. Ocular manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2016;27:552-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Generali E, Cantarini L, Selmi C. Ocular Involvement in Systemic Autoimmune Diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;49:263-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Patil SA, Cross RK. Update in the management of extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15:314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Crohn BB. Ocular lesions complicating ulcerative colitis. Am J Med Sci. 1925;169:260-267. |

| 43. | Danese S, Semeraro S, Papa A, Roberto I, Scaldaferri F, Fedeli G, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. Extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7227-7236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 44. | Ghanchi FD, Rembacken BJ. Inflammatory bowel disease and the eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:663-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Veloso FT, Carvalho J, Magro F. Immune-related systemic manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. A prospective study of 792 patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;23:29-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Salmon JF, Wright JP, Murray AD. Ocular inflammation in Crohn’s disease. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:480-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Ricart E, Panaccione R, Loftus EV Jr, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. Autoimmune disorders and extraintestinal manifestations in first-degree familial and sporadic inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:207-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Katsanos A, Asproudis I, Katsanos KH, Dastiridou AI, Aspiotis M, Tsianos EV. Orbital and optic nerve complications of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:683-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Roberts H, Rai SN, Pan J, Rao JM, Keskey RC, Kanaan Z, Short EP, Mottern E, Galandiuk S. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease and the influence of smoking. Digestion. 2014;90:122-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | McGrath J, McDonald JW, Macdonald JK. Transdermal nicotine for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;CD004722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Thomas GA, Rhodes J, Green JT. Inflammatory bowel disease and smoking--a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:144-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Santeford A, Wiley LA, Park S, Bamba S, Nakamura R, Gdoura A, Ferguson TA, Rao PK, Guan JL, Saitoh T. Impaired autophagy in macrophages promotes inflammatory eye disease. Autophagy. 2016;12:1876-1885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Girardin M, Waschke KA, Seidman EG. A case of acute loss of vision as the presenting symptom of Crohn’s disease. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:695-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Cheung O, Regueiro MD. Inflammatory bowel disease emergencies. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:1269-1288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Lin P, Tessler HH, Goldstein DA. Family history of inflammatory bowel disease in patients with idiopathic ocular inflammation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:1097-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Karmiris K, Avgerinos A, Tavernaraki A, Zeglinas C, Karatzas P, Koukouratos T, Oikonomou KA, Kostas A, Zampeli E, Papadopoulos V. Prevalence and Characteristics of Extra-intestinal Manifestations in a Large Cohort of Greek Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:429-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 57. | Manser CN, Borovicka J, Seibold F, Vavricka SR, Lakatos PL, Fried M, Rogler G; investigators of the Swiss Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort Study. Risk factors for complications in patients with ulcerative colitis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4:281-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Isene R, Bernklev T, Høie O, Munkholm P, Tsianos E, Stockbrügger R, Odes S, Palm Ø, Småstuen M, Moum B; EC-IBD Study Group. Extraintestinal manifestations in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: results from a prospective, population-based European inception cohort. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:300-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Cloché V, Buisson A, Tréchot F, Batta B, Locatelli A, Favel C, Premy S, Collet-Fenetrier B, Fréling E, Lopez A. Ocular symptoms are not predictive of ophthalmologic inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:195-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Cury DB, Moss AC. Ocular manifestations in a community-based cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1393-1396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Felekis T, Katsanos K, Kitsanou M, Trakos N, Theopistos V, Christodoulou D, Asproudis I, Tsianos EV. Spectrum and frequency of ophthalmologic manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective single-center study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:29-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Christodoulou DK, Katsanos KH, Kitsanou M, Stergiopoulou C, Hatzis J, Tsianos EV. Frequency of extraintestinal manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Northwest Greece and review of the literature. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:781-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Watson PG, Hayreh SS. Scleritis and episcleritis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1976;60:163-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 373] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Watson PG, Young RD. Scleral structure, organisation and disease. A review. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:609-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Loftus EV Jr. Management of extraintestinal manifestations and other complications of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2004;6:506-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Mady R, Grover W, Butrus S. Ocular complications of inflammatory bowel disease. ScientificWorldJournal. 2015;2015:438402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Mintz R, Feller ER, Bahr RL, Shah SA. Ocular manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:135-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Williams H, Walker D, Orchard TR. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008;10:597-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Pasadhika S, Rosenbaum JT. Update on the use of systemic biologic agents in the treatment of noninfectious uveitis. Biologics. 2014;8:67-81. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT; Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:509-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2474] [Cited by in RCA: 3237] [Article Influence: 161.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Mochizuki M, Sugita S, Kamoi K, Takase H. A new era of uveitis: impact of polymerase chain reaction in intraocular inflammatory diseases. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2017;61:1-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Haider D, Dhawahir-Scala FE, Strouthidis NG, Davies N. Acute panuveitis with hypopyon in Crohn’s disease secondary to medical therapy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2007;1:42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Awotesu O, Missotten T, Pitcher MC, Lynn WA, Lightman S. Uveitis in a patient receiving rifabutin for Crohn’s disease. J R Soc Med. 2004;97:440-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Birnbaum AD, Little DM, Tessler HH, Goldstein DA. Etiologies of chronic anterior uveitis at a tertiary referral center over 35 years. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2011;19:19-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Colìa R, Corrado A, Cantatore FP. Rheumatologic and extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel diseases. Ann Med. 2016;48:577-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Paroli MP, Spinucci G, Bruscolini A, La Cava M, Abicca I. Uveitis preceding Crohn’s disease by 8 years. Int Ophthalmol. 2011;31:413-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Taleban S, Li D, Targan SR, Ippoliti A, Brant SR, Cho JH, Duerr RH, Rioux JD, Silverberg MS, Vasiliauskas EA. Ocular Manifestations in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Are Associated with Other Extra-intestinal Manifestations, Gender, and Genes Implicated in Other Immune-related Traits. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:43-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Lau CH, Comer M, Lightman S. Long-term efficacy of mycophenolate mofetil in the control of severe intraocular inflammation. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;31:487-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Kaplan-Messas A, Barkana Y, Avni I, Neumann R. Methotrexate as a first-line corticosteroid-sparing therapy in a cohort of uveitis and scleritis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2003;11:131-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Muñoz-Fernández S, Hidalgo V, Fernández-Melón J, Schlincker A, Bonilla G, Ruiz-Sancho D, Fonseca A, Gijón-Baños J, Martín-Mola E. Sulfasalazine reduces the number of flares of acute anterior uveitis over a one-year period. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1277-1279. [PubMed] |

| 81. | Uthman I. Pharmacological therapy of vasculitis: an update. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2004;4:177-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Levesque BG, Sandborn WJ, Ruel J, Feagan BG, Sands BE, Colombel JF. Converging goals of treatment of inflammatory bowel disease from clinical trials and practice. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:37-51.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2012;380:1590-1605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1347] [Cited by in RCA: 1529] [Article Influence: 117.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Baughman RP, Bradley DA, Lower EE. Infliximab in chronic ocular inflammation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;43:7-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Rispo A, Scarpa R, Di Girolamo E, Cozzolino A, Lembo G, Atteno M, De Falco T, Lo Presti M, Castiglione F. Infliximab in the treatment of extra-intestinal manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Scand J Rheumatol. 2005;34:387-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Baltatzis S, Tufail F, Yu EN, Vredeveld CM, Foster CS. Mycophenolate mofetil as an immunomodulatory agent in the treatment of chronic ocular inflammatory disorders. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1061-1065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Jabs DA, Rosenbaum JT, Foster CS, Holland GN, Jaffe GJ, Louie JS, Nussenblatt RB, Stiehm ER, Tessler H, Van Gelder RN. Guidelines for the use of immunosuppressive drugs in patients with ocular inflammatory disorders: recommendations of an expert panel. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:492-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 657] [Cited by in RCA: 665] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Huang V, Mishra R, Thanabalan R, Nguyen GC. Patient awareness of extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e318-e324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Hwang IP, Jordan DR, Acharya V. Lacrimal gland inflammation as the presenting sign of Crohn’s disease. Can J Ophthalmol. 2001;36:212-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Mochizuki K, Sawada A, Katsumura N. Case of lacrimal gland inflammation associated with ulcerative colitis. Int Ophthalmol. 2010;30:109-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Boukouvala S, Giakoup-Oglou I, Puvanachandra N, Burton BJ. Sequential right then left acute dacryoadenitis in Crohn’s disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:pii: bcr2012006799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Jakobiec FA, Rashid A, Lane KA, Kazim M. Granulomatous dacryoadenitis in regional enteritis (crohn disease). Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158:838-844.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Diaz-Valle D, Benitez del Castillo JM, Fernandez Aceñero MJ, Pascual Allen D, Moriche Carretero M. Bilateral lid margin ulcers as the initial manifestation of Crohn disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:292-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Leibovitch I, Ooi C, Huilgol SC, Reid C, James CL, Selva D. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans of the eyelids case report and review of the literature. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1809-1813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Garrity JA, Coleman AW, Matteson EL, Eggenberger ER, Waitzman DM. Treatment of recalcitrant idiopathic orbital inflammation (chronic orbital myositis) with infliximab. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:925-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Verma S, Kroeker KI, Fedorak RN. Adalimumab for orbital myositis in a patient with Crohn’s disease who discontinued infliximab: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Foroozan R, Sambursky R. Ocular myasthenia gravis and inflammatory bowel disease: a case report and literature review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:1186-1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Roszkowska AM, Spinella R, Aragona P. Recurrence of Salzmann nodular degeneration of the cornea in a Crohn’s disease patient. Int Ophthalmol. 2013;33:185-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Zullow S, Fazelat A, Farraye FA. Central Serous Chorioretinopathy in a Patient with Ulcerative Colitis with Pouchitis on Budesonide-EC. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:E19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Geyshis B, Katz G, Ben-Horin S, Kopylov U. A patient with ulcerative colitis and central serous chorioretinopathy--a therapeutic dilemma. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e66-e68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Assadsangabi A, Majid MA, Bell A. A rare ocular complication of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:e7-e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Ugarte M, Wearne IM. Serpiginous choroidopathy: an unusual association with Crohn’s disease. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002;30:437-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Casalino G, Querques G, Corvi F, Borrelli E, Triolo G, Ramirez GA, Bandello F. Choroidal neovascularization in a patient with Crohn’s disease. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2014;5:249-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Thomas BJ, Emanuelli AA, Berrocal AM. Unilateral choroidal neovascular membrane as a herald lesion for Crohn’s disease. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2014;45:62-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Unal A, Sipahioglu MH, Akgun H, Yurci A, Tokgoz B, Erkilic K, Oymak O, Utas C. Crohn’s disease complicated by granulomatous interstitial nephritis, choroidal neovascularization, and central retinal vein occlusion. Intern Med. 2008;47:103-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Saatci OA, Koçak N, Durak I, Ergin MH. Unilateral retinal vasculitis, branch retinal artery occlusion and subsequent retinal neovascularization in Crohn’s disease. Int Ophthalmol. 2001;24:89-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Larsson J, Hansson-Lundblad C. Central retinal vein occlusion in two patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Retina. 2000;20:681-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Buchman AL, Babbo AM, Gieser RG. Central retinal vein thrombosis in a patient with ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:1847-1849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Yamane Ide S, Reis Rda S, Vieira de Moraes H Jr. [Retinal central vein occlusion in remission of Crohn’s disease: case report]. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2007;70:1034-1036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Vayalambrone D, Ivanova T, Misra A. Nonischemic central retinal vein occlusion in an adolescent patient with ulcerative colitis. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2011;2011:963583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Falavarjani KG, Parvaresh MM, Shahraki K, Nekoozadeh S, Amirfarhangi A. Central retinal artery occlusion in Crohn disease. J AAPOS. 2012;16:392-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Abdul-Rahman AM, Raj R. Bilateral retinal branch vascular occlusion-a first presentation of crohn disease. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2010;4:102-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Siqueira RC, Kaiser Junior RL, Ruiz LP, Ruiz MA. Ischemic retinopathy associated with Crohn’s disease. Int Med Case Rep J. 2016;9:197-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Fuentes-Páez G, Martínez-Osorio H, Herreras JM, Calonge M. Subretinal fibrosis and uveitis syndrome associated with ulcerative colitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:333-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Munk MR, Jampol LM, Cunha Souza E, de Andrade GC, Esmaili DD, Sarraf D, Fawzi AA. New associations of classic acute macular neuroretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100:389-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | McClelland C, Zaveri M, Walsh R, Fleisher J, Galetta S. Optic perineuritis as the presenting feature of Crohn disease. J Neuroophthalmol. 2012;32:345-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Felekis T, Katsanos KH, Zois CD, Vartholomatos G, Kolaitis N, Asproudis I, Tsianos EV. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy in a patient with Crohn’s disease and aberrant MTHFR and GPIIIa gene variants. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:471-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Mason JO 3rd. Bilateral phakic cystoid macular edema associated with Crohn’s disease. South Med J. 2002;95:1079-1080. [PubMed] |

| 119. | De Franceschi P, Costagliola C, Soreca E, Di Meo A, Giacoia A, Romano A. Pattern dystrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium in Crohn’s disease. A case report. Ophthalmologica. 2000;214:441-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 120. | Villain MA, Pageaux GP, Veyrac M, Arnaud B, Harris A, Greenfield DS. Effect of acetazolamide on ocular hemodynamics in pseudotumor cerebri associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:778-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 121. | Matet A, Daruich A, Beydoun T, Cosnes J, Bourges JL. Systemic adalimumab induces peripheral corneal infiltrates: a case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015;15:57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 122. | Marticorena-Álvarez P, Chaparro M, Pérez-Casas A, Muriel-Herrero A, Gisbert JP. Probable diffuse retinopathy caused by adalimumab in a patient with Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:950-953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 123. | Chan JW, Castellanos A. Infliximab and anterior optic neuropathy: case report and review of the literature. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;248:283-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 124. | Puli SR, Benage DD. Retinal vein thrombosis after infliximab (Remicade) treatment for Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:939-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 125. | Veerappan SG, Kennedy M, O’Morain CA, Ryan BM. Retinal vein thrombosis following infliximab treatment for severe left-sided ulcerative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:588-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 126. | Cherian A, Soumya CV, Iype T, Mathew M, Sandeep P, Thadam JK, Chithra P. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome with PLEDs-plus due to mesalamine. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2014;5:72-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 127. | da Rocha Lima B, Pichi F, Lowder CY. Night blindness and Crohn’s disease. Int Ophthalmol. 2014;34:1141-1144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 128. | Abegunde AT, Muhammad BH, Ali T. Preventive health measures in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:7625-7644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 129. | Paul S, Wand M, Emerick GT, Richter JM. The role of latanoprost in an inflammatory bowel disease flare. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2014;2:232-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |