Published online Aug 14, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i30.5579

Peer-review started: May 4, 2017

First decision: June 1, 2017

Revised: June 13, 2017

Accepted: June 18, 2017

Article in press: June 19, 2017

Published online: August 14, 2017

Processing time: 102 Days and 13.7 Hours

To retrospectively evaluate the factors that influence long-term outcomes of duodenal papilla carcinoma (DPC) after standard pancreaticoduodenectomy (SPD).

This is a single-centre, retrospective study including 112 DPC patients who had a SPD between 2006 and 2015. Associations between serum levels of CA19-9 and CEA and various clinical characteristics of 112 patients with DPC were evaluated by the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test. The patients were followed-up every 3 mo in the first two years and at least every 6 mo afterwards, with a median follow-up of 60 mo (ranging from 4 mo to 168 mo). Survival analysis was conducted using the Kaplan-Meier survival and Cox proportional hazards model analysis. The difference in survival curves was evaluated with a log-rank test.

In 112 patients undergoing SPD, serum levels of CA19-9 was associated with serum levels of CEA and drainage mode (the P values were 0.000 and 0.033, respectively); While serum levels of CEA was associated with serum levels of CA19-9 and differentiation of the tumour (the P values were 0.000 and 0.033, respectively). The serum levels of CA19-9 and CEA were closely correlated (χ² = 13.277, r = 0.344, P = 0.000). The overall 5-year survival was 50.00% for 112 patients undergoing SPD. The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that increased serum levels of CA19-9, CEA, and total bilirubin were correlated with a poor prognosis, as well as a senior grade of infiltration depth, lymph node metastases, and TNM stage(the P values were 0.033, 0.018, 0.015, 0.000, 0.000 and 0.000, respectively). Only the senior grade of infiltration depth and TNM stage retained their significance when adjustments were made for other known prognostic factors in Cox multivariate analysis (RR = 2.211, P = 0.022 and RR = 2.109, P = 0.047).

For patients with DPC, the serum levels of CA19-9 and CEA were closely correlated, and play an important role in poor survival. Increased serum levels of total bilirubin and lymph node metastases were also correlated with a poor prognosis. The senior grade of infiltration depth and TNM stage can serve as independent prognosis indexes in the evaluation of patients with DPC after SPD.

Core tip: For duodenal papilla carcinoma (DPC), standard pancreaticoduodenectomy (SPD) is still the most important treatment. However, the prognosis assessment for DPC after SPD is not yet clear. So we conducted a long-term follow-up and observation with a large sample. Our study demonstrated that the serum levels of CA19-9 and CEA were closely correlated and played an important role in poor survival. Increased serum levels of total bilirubin and lymph node metastases were also correlated with a poor prognosis. The senior grade of infiltration depth and TNM stage can serve as independent prognosis indexes for patients with DPC after SPD.

- Citation: Lian PL, Chang Y, Xu XC, Zhao Z, Wang XQ, Xu KS. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for duodenal papilla carcinoma: A single-centre 9-year retrospective study of 112 patients with long-term follow-up. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(30): 5579-5588

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i30/5579.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i30.5579

The incidence rate of primary duodenal papilla carcinoma (DPC) is low, only accounting for 0.01% of malignant tumours and accounting for 5% of gastrointestinal malignant tumours[1]. It has been reported in the literature that among malignant tumours primarily occurring in the duodenum, 60% are diagnosed as DPC[2], and the incidence rate of DPC in periampullary carcinoma is the highest. A series of studies have demonstrated that there is a higher excision rate and better prognosis of DPC than other malignant tumours around the duodenal ampulla, and the survival rate within 5 years after the operation is in the range of 50%-60%[3].

For DPC, Standard pancreaticoduodenectomy (SPD) is still the most important treatment mode[4-6]. Based on a large number of studies, there are still many disputes concerning the prognosis assessment for primary DPC after SPD, and there is lack of long-term follow-up and observation of a large sample.

Therefore, the main objective of this study was to review and report our own single-centre data of 112 patients with DPC at the PLA General Hospital between 2006 and 2015 to evaluate factors influencing outcome after radical SPD surgery.

A total of 112 patients with DPC who received SPD in the PLA General Hospital from August 2006 to November 2015 were enrolled. In this study, all patients were confirmed as DPC according to postoperative pathological examinations. There were 74 males and 38 females, with a median age of 57.95 years. The disease course was 0.13-15 years.

This study only enrolled patients who received SPD due to DPC. The following patients were not enrolled: patients who had received radiotherapy and chemotherapy before the operation; patients who received endoscopic local excision of benign tumours of the duodenum; patients who could not tolerate SPD because of body conditions; and patients with complicated malignant tumours at other sites.

All patients and/or a family member signed a written informed consent form, in which the nature of the diseases, possible therapeutic methods and postoperative potential complications were detailed. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the PLA General Hospital and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards specified in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

The most common clinical manifestation was jaundice; other symptoms included body weight decreases and epigastric discomfort. In addition, there were 20 patients with cholangitis symptoms such as intermittent or acute fever. Common concomitant diseases included hypertension, heart diseases and diabetes mellitus. The medical history of other patients included 5 cases of endoscopic local excision and4 cases of choledocholithotomy.

Routine blood tests were carried out for all patients before the operation, including blood routine, hepatic and renal function, biochemical indicators, blood coagulation series and tumour markers.

There were 87 patients with increased bilirubin more than 17.1 μmol/L, of whom there were 69 patients with increased bilirubin more than 34.2 μmol/L. Preoperative tests of tumour markers mainly included CA19-9 and CEA. There were 39 patients with CA19-9 higher than 120 U/mL, while there were only 16 patients with CEA higher than 5 ng/mL.

Preoperative routine ultrasound Band CT examinations were carried out. Intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct extension suggested that low-level biliary obstruction was the most common manifestation on CT. Preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) examinations were carried out for 92 patients, during which the conditions of duodenal papilla were directly observed under an endoscope, and in 64 of them, biopsy and pathological examinations were performed before the operation, which confirmed the pathological diagnosis. In 34 patients, a biliary tract prosthesis or a drainage tube was inserted during ERCP to drain bile as an active preoperative preparation measure.

SPD was carried out for all patients. During the operation, it was found that in 2 cases, there was remote lymph node metastases, which made radical SPD impossible; therefore, they were excluded. For all pancreas stumps, anastomosis of the pancreatic duct and jejunum was carried out, and the anastomosis modes were categorized into anastomosis of the pancreatic duct and jejunal mucous membrane and invaginated pancreaticoenterostomy according to the diameter of the pancreatic duct and the size of pancreas amputation stump, with 90 cases and 22 cases, respectively. Intraoperative exploration found that in 34 cases, the diameter of the main pancreatic duct was greater than 4 mm; in 78 cases, it was smaller than 4 mm. For the intraoperative anastomosis of the pancreatic duct and jejunum, one end of a support tube was placed in the main pancreatic duct, and the other end was placed inside the jejunum or outside the abdominal wall to drain liquid. According to the position of the support tube, pancreatic duct drainage modes were divided into internal drainage and external drainage, with 85 cases and 27 cases, respectively. According to the different habits of operators, the jejunum input side to the output side anastomosis (Braun anastomosis) was added, with the position 8 cm under the gastro-intestinal anastomotic stoma. In 54 cases, Braun anastomosis was added. All operations were performed by chief physicians with rich experience.

For all patients, conventional postoperative treatment of the pancreas was carried out. Before being transferred back to the patients’ rooms, they were observed for at least one day in the intensive care unit. After the operation, 100 μg of octreotide was subcutaneously injected three times daily in all patients for 7 continuous days. On the second day after the operation, routine blood, liver and kidney function tests were carried out; on the third day after the operation, an abdominal Colour Doppler Ultrasound examination was carried out; and 7 d after the operation, an abdominal CT examination was carried out to observe the conditions of the abdomen. Before the end of the operation, a drainage tube was placed in the pancreaticoenteric anastomosis, cholecysto-colonic anastomosis and gastrojejunostomy anastomosis, and the amount, colour and description of the draining liquid were recorded every day.

After the operation, the pancreaticoenteric drainage tube was removed when the amylase level was less than 300 U/L (less than two times the serum amylase level) inside the drainage tube, the drainage amount was less than 50 mL each day, or the drainage duration exceeded 10 d after the operation.

According to the diagnosis criteria defined by the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF)[7], a pancreatic fistula was defined as follows: 3 or more days after the operation, the draining liquid could be measured, and the activity of amylase was 3 times higher than that of the serum amylase activity. Pancreatic fistulas consisted of three grades (Grades A, B, and C) according to the clinical events of the patients’ hospitalizations. Grade A pancreatic fistulas required no change from the normal clinical approach, did not delay discharge, and usually could be resolved through the removal of the retained operation drainage tube. Grade B pancreatic fistulas required a change of treatment strategy or adjustment of the clinical approach (for instance, fasting, total parenteral nutrition support, or the addition of antibiotics or somatostatin), delayed discharge, or needed readmission for treatment after discharge. If, according to the patients’ pathogenetic conditions, invasive procedures were needed, the grade of the pancreatic fistula was upgraded to Grade C. Grade C pancreatic fistulas required a significant change of the treatment strategy or adjustment of the clinical approach; if clinical symptoms were aggravated and there were complications, such as sepsis and organ dysfunction, exploration through reoperation might be needed. Grade C pancreatic fistulas were often accompanied by complications, leading to an increased probability of postoperative death.

A biliary fistula was diagnosed if there was persistent secretion of bilirubin-rich drainage fluid of more than 50 mL per day or if secretion continued after the 10th postoperative day[8].

Postoperative bleeding was defined as the need for more than 2 units of red blood cells more than 2.4 h after surgery or relaparotomy for bleeding.

The nasogastric tube was removed when the drainage decreased to less than 200 mL per 24 h[8].

Delayed gastric emptying was defined as gastric stasis requiring nasogastric intubation for 10 or more days or the inability to tolerate a regular diet on the 14th postoperative day[9].

All excised specimens were examined in detail by two independent pathological experts; the contents observed included the nature of the tumours, size, infiltration depth, peripheral bile duct, nerves and pancreatic tissue infiltration, lymph node metastases, conditions of the tissue incisal margin (including common bile duct incisal margin, pancreas incisal margin, portal vein and mesenteric blood vessels incisal margin, stomach and jejunum incisal margin),tumour staging, etc. The TNM stage was done according to the UICC standard, version 7[10].

According to the measurement of postoperative gross specimens, there were 36 cases with a diameter greater than 2 cm and 76 cases with a diameter smaller than 2 cm. In 24 patients, lymph node metastases were positive after the operation, and in 88 patients lymph node metastases were negative. The range of lymph node metastases included pancreas peripheral lymph nodes (10 cases), duodenum peripheral lymph nodes (8 cases), common bile duct peripheral lymph nodes (4 cases), and superior mesenteric lymph nodes (2 cases).

According to the infiltration depth of tumours into the duodenum wall, tumours involved the superficial muscular layer (14 cases),deep muscular layer or full-thickness (34 cases).While for tumours penetrating the intestinal wall and infiltrating the peripheral tissues, the peripheral tissues that were mainly involved included pancreas (35 cases), the bile duct (24 cases), nerves (5 cases), etc.

Telephone and outpatient follow-ups were performed. The patients were followed-up every 3 mo in the first two years and at least every 6 mo afterwards, with a median follow-up of 60 mo (ranging from 4 mo to 168 mo). When necessary, re-examinations by CT and MRI were carried out.

Analysis was carried out with SPSS 16.0 statistical software. Associations between serum levels of CA19-9 and CEA and various clinical characteristics of 112 patients were evaluated by the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test. Survival analysis was conducted using the Kaplan-Meier survival and Cox proportional hazards model analysis. The difference in survival curves was evaluated with a log-rank test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

In this study, no patients died during the operation. Forty-three patients developed one or more complications after the operation, with an incidence rate of 38.39% (43/112). The most common postoperative complications included pancreatic fistula, biliary fistula, intra-abdominal bleeding, gastric emptying disorders and peritoneal cavity infection.

Twenty-one patients developed postoperative pancreatic fistula, according to the diagnosis criteria of the ISGPF. There were 9 cases of Grade A pancreatic fistulas, 8 cases of Grade B pancreatic fistulas, and 4 cases of Grade C pancreatic fistulas. We also found that anastomosis of the pancreatic duct and jejunal mucous membrane and invaginated pancreaticoenterostomy had no influence on pancreatic fistulas. However, the incidence rate of pancreatic fistulas in patients with a pancreatic duct with a diameter greater than 4 mm was significantly lower than that in patients with a pancreatic duct with a diameter smaller than 4 mm. The incidence rate of postoperative biliary fistula was 1.78% (2/112). Seven patients developed a peritoneal cavity infection and 5 patients developed gastric emptying disorders.

After the operation, 2 patients needed reoperation, with an incidence rate of 1.78% (2/112). Of them, 4 patients received another laparotomy because of pancreatic fistulas and 2 patients underwent reoperation only because of intraabdominal bleeding. One patient experienced intraabdominal massive haemorrhage because of pancreatic fistulas, and although reoperation was performed, he still died.

We characterized the serum levels of CA19-9 and CEA from 112 DPC patients. For serum levels of CA19-9, 73 (65.17%) were lower than 120 U/mL, defined as negative, with 39 (34.82%) positive. For serum levels of CEA, 96 (85.71%) were lower than 5 ng/mL, defined as negative, with 16 (14.29%) positive.

As in our clinical correlation studies, serum levels of CA19-9 and CEA were compared with DPC characteristics and risk factors (Table 1). The following analysis showed that serum levels of CA19-9 was associated with serum levels of CEA and drainage mode (the P values were 0.000 and 0.033, respectively); While serum levels of CEA was associated with serum levels of CA19-9 and differentiation of the tumour (the P values were 0.000 and 0.033, respectively). The serum levels of CA19-9 and CEA were closely correlated (χ² = 13.277, r = 0.344, P = 0.000). No evidence of a significant association was observed between alteration of serum levels of CA19-9 or CEA and other characteristics or risk factors.

| Characteristic | No. | Serum CA19-9 | P value | Serum CEA | P value | ||

| Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | ||||

| Gender | 0.350 | 0.807 | |||||

| Male | 74 | 46 | 28 | 63 | 11 | ||

| Female | 38 | 27 | 11 | 33 | 5 | ||

| Age (yr) | 0.621 | 0.699 | |||||

| < 60 | 61 | 41 | 20 | 53 | 8 | ||

| > 60 | 51 | 32 | 19 | 43 | 8 | ||

| Duration (yr) | 0.938 | 0.699 | |||||

| < 1 | 54 | 35 | 19 | 47 | 7 | ||

| > 1 | 58 | 38 | 20 | 49 | 9 | ||

| Serum CA19-9 (U/mL) | 0.000 | ||||||

| < 120 | 73 | 69 | 4 | ||||

| > 120 | 39 | 27 | 12 | ||||

| Serum CEA (ng/mL) | 0.000 | ||||||

| < 5 | 96 | 69 | 27 | ||||

| > 5 | 16 | 4 | 12 | ||||

| Serum total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 0.105 | 0.526 | |||||

| < 34.2 | 43 | 32 | 11 | 38 | 5 | ||

| > 34.2 | 69 | 41 | 28 | 58 | 11 | ||

| Bile pre-drainage | 0.945 | 0.933 | |||||

| No | 78 | 51 | 27 | 67 | 11 | ||

| Yes | 34 | 22 | 12 | 29 | 5 | ||

| Tumour diameter (cm) | 0.820 | 0.934 | |||||

| < 2 | 76 | 49 | 27 | 65 | 11 | ||

| > 2 | 36 | 24 | 12 | 31 | 5 | ||

| Pancreatic duct diameter (mm) | 0.351 | 0.015 | |||||

| < 4 | 78 | 53 | 25 | 71 | 7 | ||

| > 4 | 34 | 20 | 14 | 25 | 9 | ||

| Drainage mode | 0.033 | 0.928 | |||||

| Inside | 85 | 60 | 25 | 73 | 12 | ||

| Outside | 27 | 13 | 14 | 23 | 4 | ||

| End-to-end invagination | 0.184 | 0.145 | |||||

| No | 90 | 56 | 34 | 75 | 15 | ||

| Yes | 22 | 17 | 5 | 21 | 1 | ||

| Blood loss (mL) | 0.786 | 0.059 | |||||

| < 400 | 67 | 43 | 24 | 54 | 13 | ||

| > 400 | 45 | 30 | 15 | 42 | 3 | ||

| Delayed emptying | 0.227 | 0.350 | |||||

| No | 107 | 71 | 36 | 91 | 16 | ||

| Yes | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 0 | ||

| Pancreatic fistula | 0.874 | 0.166 | |||||

| No | 91 | 59 | 32 | 76 | 15 | ||

| Yes | 21 | 14 | 7 | 20 | 1 | ||

| Differentiation | 0.253 | 0.033 | |||||

| Well | 40 | 24 | 16 | 37 | 3 | ||

| Moderate | 38 | 23 | 15 | 28 | 10 | ||

| Poor | 34 | 26 | 8 | 31 | 3 | ||

| T stage | 0.946 | 0.062 | |||||

| T1 | 14 | 10 | 4 | 14 | 0 | ||

| T2 | 34 | 22 | 12 | 31 | 3 | ||

| T3 | 35 | 23 | 12 | 30 | 5 | ||

| T4 | 29 | 18 | 11 | 21 | 8 | ||

| N stage | 0.078 | 0.301 | |||||

| N0 | 88 | 61 | 27 | 77 | 11 | ||

| N1 | 24 | 12 | 12 | 19 | 5 | ||

| TNM stage | 0.682 | 0.109 | |||||

| IA | 14 | 10 | 4 | 14 | 0 | ||

| IB | 27 | 18 | 9 | 25 | 2 | ||

| IIA | 28 | 20 | 8 | 24 | 4 | ||

| IIB | 14 | 7 | 7 | 12 | 2 | ||

| III | |||||||

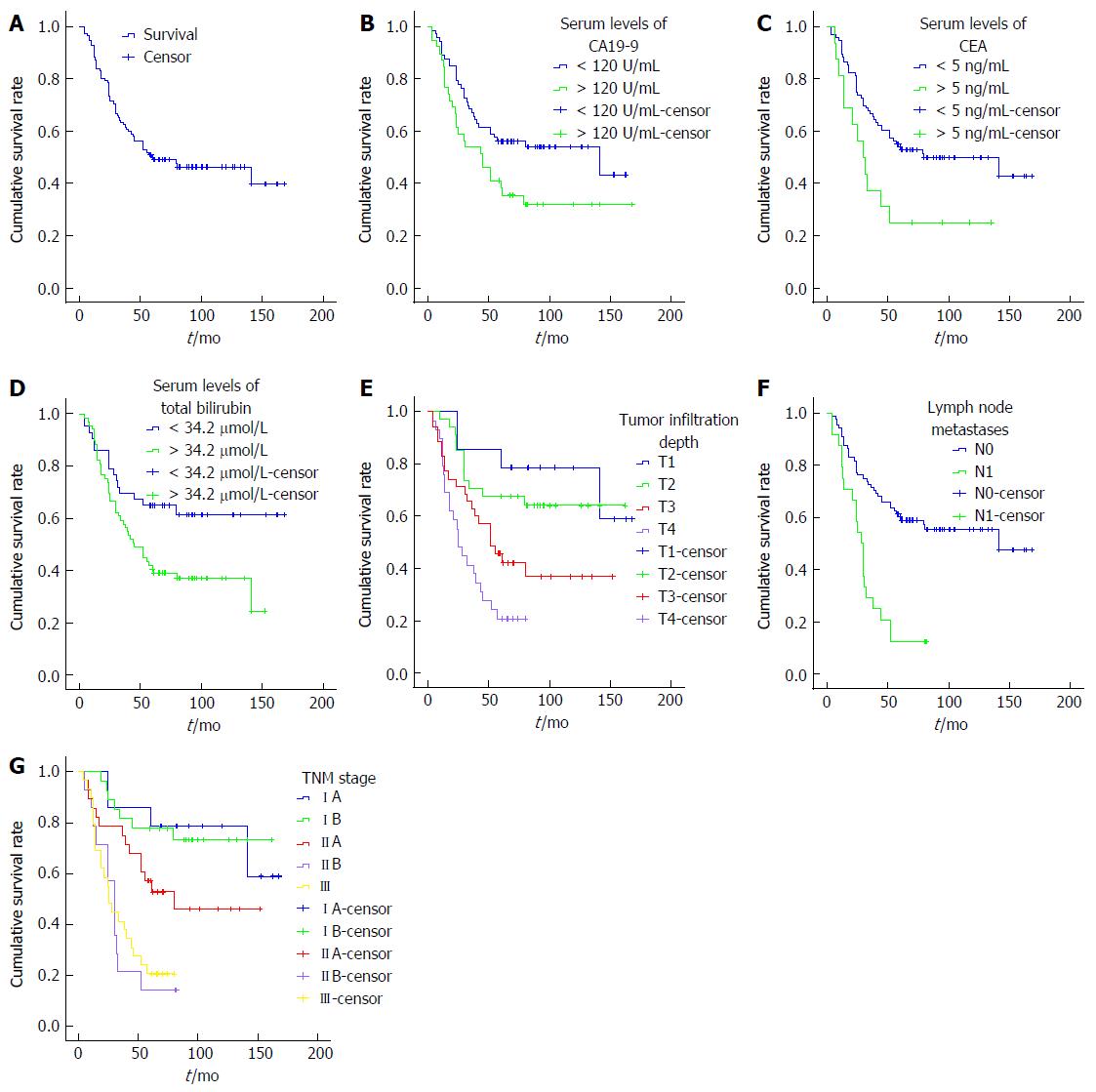

As of August 2015, we followed up all patients after the operation, with a median follow-up of 60 mo (ranging from 4 mo to 168 mo).There was a total of 52 patients with nodiseaseprogression, and of them, 48 patients lived longer than 5 years. A total of 60 patients died of this disease, with an median survival of 24.50 mo (ranging from 4 mo to 80 mo). The overall 5-year survival was 50.00% for 112 patients undergoing SPD (Figure 1A).

The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that increased serum levels of CA19-9, CEA, and total bilirubin were correlated with a poor prognosis, as well as a senior grade of infiltration depth, lymph node metastases, and TNM stage(the P values were 0.033, 0.018, 0.015, 0.000, 0.000 and 0.000, respectively) (Tables 2 and 3, Figure 1B-F).

| Factors | No. | 5 years survival | χ² | P value |

| Gender | 0.561 | 0.454 | ||

| Male | 74 | 48.6% | ||

| Female | 38 | 52.4% | ||

| Age (yr) | 0.022 | 0.883 | ||

| < 60 | 61 | 46.3% | ||

| > 60 | 51 | 48.9% | ||

| Duration (yr) | 0.409 | 0.523 | ||

| < 1 | 54 | 41.7% | ||

| > 1 | 58 | 53.4% | ||

| Serum CA19-9 (U/mL) | 4.566 | 0.033 | ||

| < 120 | 73 | 56.2% | ||

| > 120 | 39 | 38.3% | ||

| Serum CEA (ng/mL) | 5.554 | 0.018 | ||

| < 5 | 96 | 54.1% | ||

| > 5 | 16 | 25.0% | ||

| Serum total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 5.929 | 0.015 | ||

| < 34.2 | 43 | 65.1% | ||

| > 34.2 | 69 | 40.6% | ||

| Bile pre-drainage | 1.144 | 0.285 | ||

| No | 78 | 47.4% | ||

| Yes | 34 | 55.9% | ||

| Tumour diameter (cm) | 0.185 | 0.667 | ||

| < 2 | 76 | 51.3% | ||

| > 2 | 36 | 47.2% | ||

| Pancreatic duct diameter (mm) | 0.493 | 0.483 | ||

| < 4 | 78 | 51.2% | ||

| > 4 | 34 | 47.1% | ||

| Drainage mode | 0.006 | 0.939 | ||

| Inside | 85 | 48.2% | ||

| Outside | 27 | 55.3% | ||

| End-to-end invagination | 0.592 | 0.442 | ||

| No | 90 | 48.9% | ||

| Yes | 22 | 54.5% | ||

| Blood loss (mL) | 0.052 | 0.820 | ||

| < 400 | 67 | 49.2% | ||

| > 400 | 45 | 51.1% | ||

| Delayed emptying | 0.614 | 0.433 | ||

| No | 107 | 50.5% | ||

| Yes | 5 | 40.0% | ||

| Pancreatic fistula | 0.455 | 0.500 | ||

| No | 91 | 47.1% | ||

| Yes | 21 | 57.1% | ||

| Differentiation | 3.676 | 0.159 | ||

| Well | 40 | 62.4% | ||

| Moderate | 38 | 39.5% | ||

| Poor | 34 | 47.1% | ||

| Infiltration depth | 22.424 | 0.000 | ||

| T1 | 14 | 78.6% | ||

| T2 | 34 | 67.6% | ||

| T3 | 35 | 45.7% | ||

| T4 | 29 | 20.7% | ||

| lymph metastases | 21.187 | 0.000 | ||

| N0 | 88 | 60.2% | ||

| N1 | 24 | 12.5% | ||

| TNM stage | 35.041 | 0.000 | ||

| IA | 14 | 78.6% | ||

| IB | 27 | 77.8% | ||

| IIA | 28 | 57.1% | ||

| IIB | 14 | 14.3% | ||

| III | 29 | 20.7% |

| Factors | No. | 5 years survival | Median survival (95%CI)(mo) | Relative risk (95%CI) | P value |

| CA19-9 (U/mL) | 0.174 | ||||

| < 120 | 73 | 56.2% | 141.0 (3.3-278.6) | 1 | |

| > 120 | 39 | 38.3% | 45.0 (22.6-67.4) | 1.550 (0.823-2.920) | |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 0.528 | ||||

| < 5 | 96 | 54.1% | 80.0 (10.4-149.5) | 1 | |

| > 5 | 16 | 25.0% | 30.0 (18.2-41.8) | 1.270 (0.605-2.663) | |

| Bilirubin (μmol/L) | 0.264 | ||||

| < 34.2 | 43 | 65.1% | 1 | ||

| > 34.2 | 69 | 40.6% | 45.0 (29.9-60.1) | 1.408 (0.772-2.566) | |

| Differentiation | 0.137 | ||||

| Well | 40 | 62.4% | 141.0 | 1 | |

| Moderate | 38 | 39.5% | 44.0 (3.09-57.1) | 0.808 (0.399-1.635) | 0.553 |

| Poor | 34 | 47.1% | 52.0 (3.552-100.4) | 1.636 (0.814-3.285) | 0.167 |

| Infiltration depth | 0.022 | ||||

| T1 + T2 | 48 | 70.8% | 1 | ||

| T3 + T4 | 64 | 34.4% | 39.0 (26.3-51.7) | 2.211 (1.119-4.367) | |

| lymph metastases | 0.142 | ||||

| N0 | 88 | 60.2% | 141.0 | 1 | |

| N1 | 24 | 12.5% | 28.0 (6.1-113.9) | 1.744 (0.830-3.666) | |

| TNM stage | 0.047 | ||||

| IA + IB + IIA | 69 | 69.5% | 1 | ||

| IIB + III | 43 | 18.6% | 28.0 (21.6-34.4) | 2.109 (1.010-4.406) |

Only the senior grade of infiltration depth (T3/4) and TNM stage (IIB/III) retained their significance when adjustments were made for other known prognostic factors in Cox multivariate analysis (RR = 2.211, P = 0.022 and RR = 2.109, P = 0.047).

The incidence rate of DPC is low, only accounting for 5% of gastrointestinal malignant tumours[11-13]. However, because the special position of duodenal papilla, i.e., it is located at the opening of pancreatic duct, early DPC may manifest as painless progressive jaundice. SPD has always been the most important treatment mode of DPC. According to the literature, it had different 5-year survival rates and factors influencing survival[14,15]. Therefore, in this study, we carried out long-term follow-up and prognosis analysis of patients with DPC who received SPD in our centre to provide a theoretical basis for prognosis improvement of the patients.

Jaundice is the most common early clinical symptom in patients with DPC, and whether treatment for jaundice should be performed before the operation is always a topic of dispute in surgery. Some scholars think that preoperative high bilirubin may inhibit hepatocyte function and induce endotoxin dysmetabolism, thereby increasing the incidence rate of postoperative complications and influences the prognosis of patients[16,17]. However, some scholars have opposing views[18,19]. In this experiment, a poor survival was found in patients with increased bilirubin more than 34.2 μmol/L, with a 5-year survival rate of 40.6% (P = 0.015). Meanwhile, 34 patients who had placement of stents or drainage tubes before the operation, live longer than the other 78 patients who did not receive treatment for jaundice, with a 5-year survival rate of 55.9% vs 47.4%, although the difference was not significantly (P = 0.285). Based on these data, we proposed that increased bilirubin more than 34.2 μmol/L plays a bad role in the survival of patients with DPC after SPD.

Tumour markers are mainly used for the detection of primary tumours and the differentiation of benign and malignant tumours, and they have good clinical guidance significance for the judgement of the efficacy of tumour treatment and their occurrence and prognosis of tumours. There is still a lack of specific tumour markers for DPC. In our study, serum levels of CA19-9 was associated with drainage mode (P = 0.033); While serum levels of CEA was associated with tumour differentiation (P = 0.033). Besides, the serum levels of CA19-9 and CEA were closely correlated (r = 0.344, P = 0.000). A study by Dorandeu et al[20] demonstrated that preoperative serum levels of CA199 and CEA were negatively related to the prognosis of patients with DPC; however, our study has opposing views. Among the 112 patients with DPC, there were 39 patients with increased serum CA19-9 and 16 patients with increased serum CEA levels. When the patients with increased levels of serum CA199were compared with the others, the 5-year survival rates were significantly lower (38.3% vs 56.2%, P = 0.033).The same tendency was present in levels of serum CEA, with the 5-year survival rates of 25.0% vs 54.1% (P = 0.018). This indicated that the serum levels of CA19-9 and CEA are worth considering as the basis of diagnosis and prognosis for patients with DPC after SPD.

Pancreas-duodenum operations may cause great trauma, and there are many postoperative complications, of which pancreatic fistula is the most common complication[21,22]. In this study, the incidence rate of pancreatic fistula was 18.75% and was mainly Grade A and B pancreatic fistulas. However, we also found that whether there is a pancreatic fistula or not is not related with the long-term survival of patients (P = 0.500). In our study, we also investigated the influence of different factors on pancreatic fistulas, and our study found that anastomosis of the pancreatic duct and jejunal mucous membrane and invaginated pancreaticoenterostomy had no influence on pancreatic fistulas; different pancreatic duct drainage modes and whether Braun anastomosis was added also had no influence on the occurrence of pancreatic fistulas.

When it comes to the relationship between the size of tumour and the prognosis of patients, the study by Di Giorgio et al[23] demonstrated that among the 64 patients who underwent SPD, the prognosis of patients with tumours with a diameter greater than 2 cm was significantly inferior to those with tumours less than 2 cm. However, the results of our study were different; there was no significant difference in prognoses between the patients with tumours with a diameter greater than 2 cm and the others, and a diameter of 2 cm is not a boundary for the difference in prognosis.

We also found that the infiltration depth of tumours is an independent factor influencing the prognosis of patients after SPD. The study by Di Giorgio et al[4] demonstrated that for patients who underwent SPD because of duodenal ampulla tumours, the prognosis of patients with Stage T1/2 tumours was significantly better than that of patients with Stage T3/4 tumours. Our study also demonstrated that the infiltration depth of tumours has influence on the prognosis of patients; even when adjustments were made for other known prognostic factors in Cox multivariate analysis, the senior grade of infiltration depth (T3/4) and TNM stage (IIB/III) retained their significance (RR = 2.211, P = 0.022 and RR = 2.109, P = 0.047).

Whether there are lymph node metastases is an important factor influencing the prognosis of malignant tumours. The study by Klein et al[24] reported that lymph node metastasis was a key factor influencing tumour recurrence and the survival of patients with ampullary carcinoma. Other studies demonstrated that the number of lymph node metastases was related to the prognosis of patients with periampullary carcinoma[25,26]. Our experiment led to the same conclusion; i.e., the 5-year survival rate of patients with positive lymph node metastases was significantly lower than that of patients with negative lymph node metastases. However, lymph node metastases could not serve as an independent factor influencing the prognosis of patients after SPD.

In conclusion, for patients with DPC, the serum levels of CA19-9 and CEA were closely correlated, and play an important role in poor survival. Increased serum levels of total bilirubin and lymph node metastases were also correlated with a poor prognosis. The senior grade of infiltration depth and TNM stage can serve as independent prognosis indexes in the evaluation of patients with DPC after SPD.

For duodenal papilla carcinoma (DPC), standard pancreaticoduodenectomy (SPD) is still the most important treatment. However, the prognosis assessment for DPC after SPD is not yet clear.

Only a few researches have focused on the prognosis assessment for DPC after SPD. According to the literature, it had different 5-year survival rates and factors influencing survival.

In this study, the authors carried out long-term follow-up and prognosis analysis of patients with DPC who received SPD in our centre to provide a theoretical basis for prognosis improvement of the patients.

The senior grade of infiltration depth and TNM stage can serve as independent prognosis indexes in the evaluation of patients with DPC after SPD.

This study is very interesting. Over all, the study was well designed, and the manuscript is well written.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Araujo RLC, Lee MW S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | DeOliveira ML, Triviño T, de Jesus Lopes Filho G. Carcinoma of the papilla of Vater: are endoscopic appearance and endoscopic biopsy discordant? J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1140-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kim MH, Lee SK, Seo DW, Won SY, Lee SS, Min YI. Tumors of the major duodenal papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:609-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Huang W, Xiong JJ, Wan MH, Szatmary P, Bharucha S, Gomatos I, Nunes QM, Xia Q, Sutton R, Liu XB. Meta-analysis of subtotal stomach-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy vs pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:6361-6373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Di Giorgio A, Alfieri S, Rotondi F, Prete F, Di Miceli D, Ridolfini MP, Rosa F, Covino M, Doglietto GB. Pancreatoduodenectomy for tumors of Vater’s ampulla: report on 94 consecutive patients. World J Surg. 2005;29:513-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Moriya T, Kimura W, Hirai I, Mizutani M, Ma J, Kamiga M, Fuse A. Nodal involvement as an indicator of postoperative liver metastasis in carcinoma of the papilla of Vater. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:549-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Winter JM, Cameron JL, Olino K, Herman JM, de Jong MC, Hruban RH, Wolfgang CL, Eckhauser F, Edil BH, Choti MA. Clinicopathologic analysis of ampullary neoplasms in 450 patients: implications for surgical strategy and long-term prognosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:379-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M; International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula Definition. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3282] [Cited by in RCA: 3496] [Article Influence: 174.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 8. | Tran KT, Smeenk HG, van Eijck CH, Kazemier G, Hop WC, Greve JW, Terpstra OT, Zijlstra JA, Klinkert P, Jeekel H. Pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy versus standard Whipple procedure: a prospective, randomized, multicenter analysis of 170 patients with pancreatic and periampullary tumors. Ann Surg. 2004;240:738-745. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Klinkenbijl JH, Jeekel J, Sahmoud T, van Pel R, Couvreur ML, Veenhof CH, Arnaud JP, Gonzalez DG, de Wit LT, Hennipman A. Adjuvant radiotherapy and 5-fluorouracil after curative resection of cancer of the pancreas and periampullary region: phase III trial of the EORTC gastrointestinal tract cancer cooperative group. Ann Surg. 1999;230:776-782; discussion 782-784. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Hermanek P, Scheibe O, Spiessl B, Wagner G. [TNM classification of malignant tumors: the new 1987 edition]. Rontgenblatter. 1987;40:200. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Nakase A, Matsumoto Y, Uchida K, Honjo I. Surgical treatment of cancer of the pancreas and the periampullary region: cumulative results in 57 institutions in Japan. Ann Surg. 1977;185:52-57. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Yamaguchi K, Enjoji M. Carcinoma of the ampulla of vater. A clinicopathologic study and pathologic staging of 109 cases of carcinoma and 5 cases of adenoma. Cancer. 1987;59:506-515. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Gudjonsson B. Periampullary adenocarcinoma: analysis of 5-year survivors. Ann Surg. 1999;230:736-737. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Seiler CA, Wagner M, Bachmann T, Redaelli CA, Schmied B, Uhl W, Friess H, Büchler MW. Randomized clinical trial of pylorus-preserving duodenopancreatectomy versus classical Whipple resection-long term results. Br J Surg. 2005;92:547-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lin PW, Lin YJ. Prospective randomized comparison between pylorus-preserving and standard pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 1999;86:603-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhu XH, Wu YF, Qiu YD, Jiang CP, Ding YT. Effect of early enteral combined with parenteral nutrition in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5889-5896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Billingsley KG, Hur K, Henderson WG, Daley J, Khuri SF, Bell RH Jr. Outcome after pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary cancer: an analysis from the Veterans Affairs National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:484-491. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Isla AM, Griniatsos J, Riaz A, Karvounis E, Williamson RC. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary malignancies: the effect of bile colonization on the postoperative outcome. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2007;392:67-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sewnath ME, Birjmohun RS, Rauws EA, Huibregtse K, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. The effect of preoperative biliary drainage on postoperative complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:726-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dorandeu A, Raoul JL, Siriser F, Leclercq-Rioux N, Gosselin M, Martin ED, Ramée MP, Launois B. Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater: prognostic factors after curative surgery: a series of 45 cases. Gut. 1997;40:350-355. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Alexakis N, Halloran C, Raraty M, Ghaneh P, Sutton R, Neoptolemos JP. Current standards of surgery for pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1410-1427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Klaiber U, Probst P, Knebel P, Contin P, Diener MK, Büchler MW, Hackert T. Meta-analysis of complication rates for single-loop versus dual-loop (Roux-en-Y) with isolated pancreaticojejunostomy reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2015;102:331-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Di Giorgio P, De Luca L, Calcagno G, Rivellini G, Mandato M, De Luca B. Detachable snare versus epinephrine injection in the prevention of postpolypectomy bleeding: a randomized and controlled study. Endoscopy. 2004;36:860-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Klein F, Jacob D, Bahra M, Pelzer U, Puhl G, Krannich A, Andreou A, Gül S, Guckelberger O. Prognostic factors for long-term survival in patients with ampullary carcinoma: the results of a 15-year observation period after pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB Surg. 2014;2014:970234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tol JA, Brosens LA, van Dieren S, van Gulik TM, Busch OR, Besselink MG, Gouma DJ. Impact of lymph node ratio on survival in patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancer. Br J Surg. 2015;102:237-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bronsert P, Kohler I, Werner M, Makowiec F, Kuesters S, Hoeppner J, Hopt UT, Keck T, Bausch D, Wellner UF. Intestinal-type of differentiation predicts favourable overall survival: confirmatory clinicopathological analysis of 198 periampullary adenocarcinomas of pancreatic, biliary, ampullary and duodenal origin. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |