Published online Oct 14, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i38.8624

Peer-review started: July 13, 2016

First decision: August 19, 2016

Revised: August 31, 2016

Accepted: September 12, 2016

Article in press: September 12, 2016

Published online: October 14, 2016

Processing time: 93 Days and 9.5 Hours

A 68-year-old man presented with progressive right lower quadrant abdominal pain and tenderness without rebound tenderness, and with constipation during the prior 9 mo. Abdomino-pelvic computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated a dilated appendix forming a fistula to the sigmoid colon. Open laparotomy revealed a bulky abdominal tumor involving appendix, cecum, and sigmoid, and extending up to adjacent viscera, without ascites or peritoneal implants. The abdominal mass was removed en bloc, including resection of sigmoid colon, cecum (with preservation of ileocecal valve), appendix, right vas deferens, testicular vessels, and minimal amounts of anterior abdominal wall; and shaving off of small parts of the walls of the urinary bladder and small bowel. Gross and microscopic pathologic examination revealed an appendix-to-sigmoid malignant fistula secondary to perforation of mucinous adenocarcinoma of the appendix with minimal local spread (stage T4). However, the surgical margins were clear, all 13 resected lymph nodes were cancer-free, and pseudomyxoma peritonei or peritoneal implants were not present. The patient did well during 1 year of follow-up with no clinical or radiologic evidence of local recurrence, metastases, or pseudomyxoma peritonei despite presenting with extensive stage T4 cancer that was debulked without administering chemotherapy, and despite presenting with malignant appendiceal perforation. This case illustrates the non-aggressive biologic behavior of this low-grade malignancy. The fistula may have prevented free spillage of cancerous cells and consequent distant metastases by containing the appendiceal contents largely within the colon.

Core tip: A patient with mucinous appendiceal adenocarcinoma had appendiceal perforation that was locally contained by a malignant appendix-to-sigmoid fistula. The patient presented with right lower quadrant pain and tenderness and constipation. Abdomino-pelvic computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed a bulky peri-appendiceal mass containing an appendix-to-sigmoid-fistula. Pathologic analysis after debulking surgery revealed a locally extensive cancer involving appendix, sigmoid, and cecum and extending up to adjacent viscera with clear surgical margins and benign lymph nodes. The patient remained free of local recurrence/metastases during 1 year of follow-up despite not receiving chemotherapy/radiotherapy. This apparently favorable outcome is due to this cancer’s nonaggressive biology, and the fistula which likely largely contained cancer cell spillage within the colon and prevented free cancer cell spillage.

- Citation: Hakim S, Amin M, Cappell MS. Limited, local, extracolonic spread of mucinous appendiceal adenocarcinoma after perforation with formation of a malignant appendix-to-sigmoid fistula: Case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(38): 8624-8630

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i38/8624.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i38.8624

Malignant colonic perforation entails a poor prognosis because of presentation with acute sepsis/peritonitis and subsequent development of gross metastases from intraperitoneal seeding of malignant cells from the perforation[1]. A case is reported of mucinous appendiceal adenocarcinoma (MAA) presenting as a bulky mass due to appendiceal perforation and fistulization, treated by debulking surgery; and presenting initially without sepsis; and subsequently at 1 year follow-up had no evident local or distant metastases despite the prior malignant appendiceal perforation. The pathophysiology of this clinical presentation and course is explained by the appendix-to-sigmoid fistula containing spillage of cancerous cells within the colon and preventing free spillage, and by the low grade, nonaggressive biology of MAA[2].

The literature was systematically reviewed using the medical subject headings/key words of: “mucinous adenocarcinoma” or “pseudomyxoma peritonei” or “appendiceal neoplasm” or “appendiceal adenocarcinoma”. Two authors independently reviewed the literature and decided by consensus which articles to incorporate in the study. This case report received exemption/approval from the William Beaumont Hospital IRB on June 16, 2016.

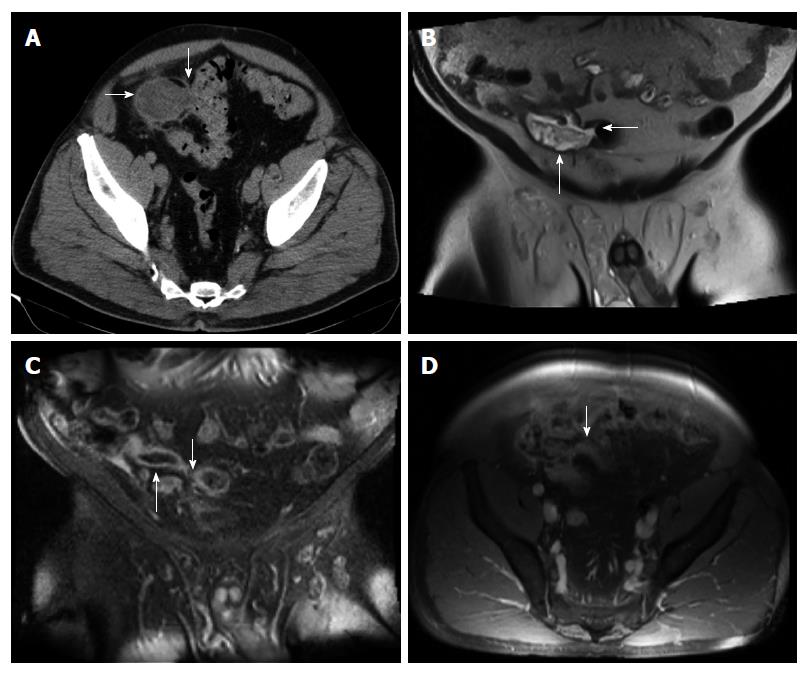

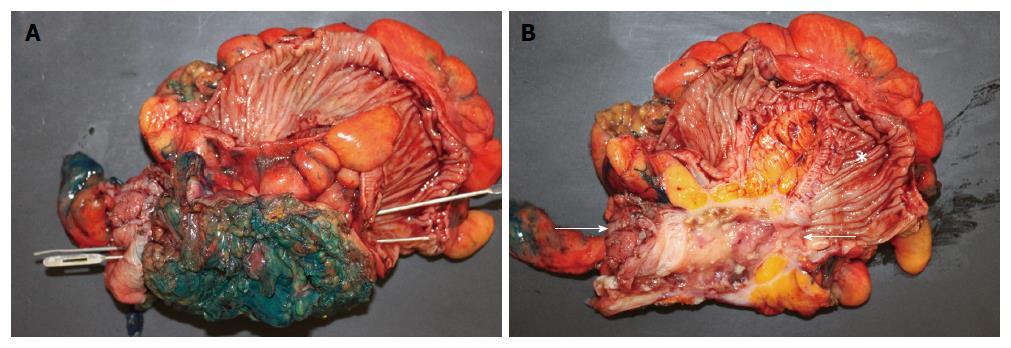

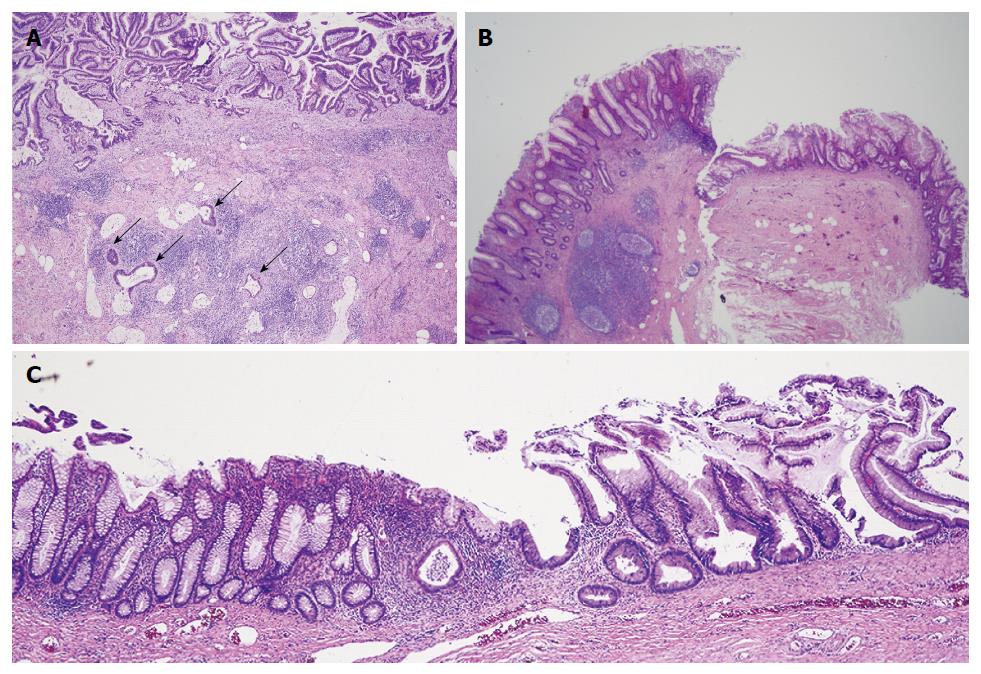

A 68-year-old man with past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and colonic diverticulosis presented with progressive right lower quadrant abdominal pain and constipation during the prior 9 mo. Colonoscopy with good cecal visualization, performed 2 years earlier for routine colon cancer screening, had revealed a normal colon and normal appendiceal orifice. Physical examination revealed normal vital signs, soft abdomen, minimal right lower quadrant tenderness, no rebound tenderness, and no palpable abdominal mass. Laboratory analysis revealed hemoglobin = 13.1 gm/dL, leukocyte count = 12000/mL, and serum bicarbonate = 28 mmol/L. Serum electrolytes, serum parameters of liver function, serum parameters of renal function, and serum lactate level were within normal limits. Abdomino-pelvic computed tomography (CT) revealed a dilated, heterogeneous, appendix with an 8-cm-long, ovoid, periappendiceal mass containing a fistula to sigmoid colon (Figure 1A), and revealed no findings suggestive of pseudomyxoma peritonei or peritoneal implants, including intraperitoneal fluid, peritoneal calcifications, or scalloping of the liver. Abdomino-pelvic magnetic resonant imaging (MRI) showed on coronal view a dilated, 8-cm-long, appendix fistulizing to the sigmoid (Figure 1B and C); and showed on axial view an abnormally thick, enhancing, appendiceal wall without significant peri-appendiceal inflammation (Figure 1D). Open laparotomy revealed an extensive mass involving appendix, cecum, sigmoid colon, anterior abdominal wall, and urinary bladder (Figure 2A); no peritoneal implants, and no pseudomyxoma peritonei. The abdominal mass was removed en-bloc, including resection of sigmoid colon, cecum (with preservation of ileocecal valve), appendix, right vas deferens, testicular vessels, and minimal amounts of anterior abdominal wall; and shaving off of small parts of the walls of the urinary bladder and small bowel. Gross pathological examination of the resected mass revealed an appendix-to-sigmoid fistula, as confirmed by a probe, from prior perforation of a promontoric (preileal/postileal appendix traveling from cecal base towards the sigmoid in the pelvis) appendix (Figure 2B). Microscopic pathology showed well-differentiated, invasive, mucinous, adenocarcinoma diffusely involving the appendix, sigmoid, and cecum through the serosa (Figure 3). Histopathology showed no invasion of adjacent organs, such as the bladder wall or anterior abdominal wall. Lymphovascular invasion and satellite peritumoral nodules were not present. All surgical margins and all 13 resected lymph nodes were devoid of cancer (Stage pT4b N0). The patient developed postoperative ileus from which he recovered, and was discharged 11 d postoperatively. No postoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy was administered. The patient was doing well 1 year later, with no ascites, pseudomyxoma peritonei, or cancer recurrence, as observed clinically by an oncologist and by repeat abdomino-pelvic CT examination.

Primary adenocarcinoma of the appendix is rare. It accounts for 0.12 cases per 1000000 patients per annum, 0.05%-0.2% of all appendectomies, about 0.2% of all gastrointestinal neoplasms, and only 6% of appendiceal cancers[3]. Appendiceal adenocarcinoma is divided into colonic, mucinous (MAA), goblet cell, and signet ring cell types[4,5]. MAA usually presents with nonspecific findings. It frequently presents with acute abdominal pain resembling acute appendicitis; sometimes presents as an abdominal mass detected by palpation or abdominal imaging, as occurred in the currently reported case; and rarely presents with nausea, vomiting, ascites, or involuntary weight loss. Due to its nonspecific presentation, it is rarely diagnosed preoperatively and usually diagnosed postoperatively by histopathological examination of the resected specimen after exploratory surgery for other suspected disease[3,6,7].

MAA, a low-grade, relatively noninvasive, cancer, rarely produces distant metastases, except when signet ring cells occur in addition to mucin (denoted separately as signet ring cell cancer) that indicates high-grade mucinous adenocarcinoma[8]. No cases of distant lymphatic or hematogenous metastases were reported by Nitecki et al[2] among 52 patients with MAA, even in patients with severe intraperitoneal disease, but one patient had pulmonary metastases from MAA in a case report by Gourgiotis et al[3]. Local nodal involvement is also uncommon when the cancer involves only the mucosa or submucosa[9], but the incidence increases to 20%-25% when the primary cancer more deeply invades the appendiceal wall[10,11]. Ovarian involvement from MAA is, however, common in females; among 23 female patients undergoing oophorectomy reported by Niteck[2], 13 had ovarian involvement. Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) occurs when mucin escapes intraperitoneally, often secondary to appendiceal perforation (disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis), or uncommonly from malignant peritoneal seeding of mucin-producing cancerous cells (disseminated peritoneal carcinomatosis)[10,12]. MAA frequently causes appendiceal perforation, as occurred in this case, attributed to the mucinous gel obstructing the lumen and the narrow appendiceal lumen. For example, in a comprehensive literature review encompassing 316 cases of appendiceal adenocarcinomas, 55% of patients presented with appendiceal perforation[13,14].

Data on therapy are sparse because MAA is rare. Therapy depends upon pathologic stage. Right hemicolectomy is recommended after an initial appendectomy when pathologic examination of the resected specimen reveals MAA localized to the appendix. Nitecki et al[2] reported in a study of 29 patients with clinically localized MAA, a 73% 5-year-survival after right hemicolectomy versus a 44% 5-year-survival after appendectomy alone; patients undergoing right hemicolectomy after initial appendectomy have residual cancer detected in up to 27% of right hemicolectomy specimens[10]. Abdomino-pelvic CT and colonoscopy should be performed before undergoing the right hemicolectomy after initial appendectomy to detect synchronous colon cancers which occur in up to 18%-27% of patients[2,7]. Women should standardly undergo oophorectomy because of frequent ovarian metastases[2,7].

Presence of peritoneal spread requires surgical debulking by primary tumor excision, right hemicolectomy, lymph node dissection, omentectomy, peritoneotomy, and removal of malignant ascites[7]. Patients with intraperitoneal lymphadenopathy or PMP might theoretically benefit from adjuvant intraperitoneal chemotherapy, using 5-flurouracil and levamisol, but this chemotherapy is not of proven benefit and therefore controversial[7,10,15]. However, intraperitoneal chemotherapy is generally recommended if peritoneal implants are identified[16-18]. Frequent surveillance colonoscopy is recommended after surgery because of an approximately 17% incidence of metachronous colon cancer[2,7].

The current case illustrates the nonaggressive biologic behavior of this low-grade malignancy. The patient presented with abdominal pain and constipation for 9 mo; laparotomy revealed a bulky tumor involving appendix, cecum, sigmoid colon, and adjacent viscera. The promontoric appendiceal location (appendix located in pelvis and traveling towards the sigmoid, as observed intraoperatively), an appendiceal anatomic variant that occurs in several percent of patients[19,20], may have promoted sigmoid fistulization. The adhesiveness of mucin may also have promoted fistulization. Rapid fistulization presumably contained the leakage of mucin and cancerous cells within the fistula and sigmoid colon, and prevented free intraperitoneal spillage, as would have been expected from free appendiceal perforation. Despite appendiceal rupture, malignant fistulization, and pathologic T4 stage, no lymph nodes were involved at presentation (stage N0), and no recurrent tumor or PMP was detected, by clinical examination or repeat abdomino-pelvic CT, 1 year after the initial surgery without chemotherapy. The patient had undergone colonoscopy 2 years before the surgery which had not detected MAA; appendiceal cancer is commonly missed at colonoscopy because the cancer is located deep in the appendix and not visible from the cecal lumen[21].

This study is limited because it reports only one case, and surgical cure cannot be definitively claimed because of only 1 year of follow-up. However, a favorable prognosis is indicated by the clear surgical margins, absence of lymph node involvement, absence of the aggressive signet ring cell histology, and absence of PMP or distant metastases detected at surgery or 1 year thereafter. In conclusion, this patient had no evident local, peritoneal, or distant metastasis 1 year after undergoing debulking surgery without chemotherapy, despite appendicular perforation and malignant fistulization from MAA. This phenomenon is explained by the appendix-to-sigmoid fistula containing the spillage of cancerous cells within the colon and preventing free spillage, by the low grade, nonaggressive nature of MAA[2], and perhaps by the adhesiveness of mucin which might promote containment of appendiceal spillage.

The authors hereby acknowledge Kiran Nandalur, M.D, Associate Professor of Radiology, William Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, Michigan United States 48073, as a minor author of the paper for the radiologic interpretations of the abdomino-pelvic CT and MRI.

A 68-year-old man presented with progressive constipation and right lower quadrant (RLQ) abdominal pain for the prior 9 months and with right lower quadrant tenderness, without rebound tenderness, on physical examination. Colonoscopy with good cecal visualization, performed 2 years earlier for routine colon cancer screening, had revealed a normal colon and normal appendiceal orifice.

The differential diagnosis based on patient history of RLQ abdominal pain and constipation for 9 mo, and physical finding of RLQ tenderness without rebound tenderness is very broad. This mild clinical presentation contrasts with the severe final pathologic diagnosis of mucinous appendiceal adenocarcinoma with perforation/fistulization. This discrepancy is explained by the relatively non-aggressive biology of this cancer, prevention of acute peritonitis and distant cancer spread from containment of the appendiceal perforation by fistulization, and perhaps the adhesiveness of the mucin produced by this cancer which may promote fistulization.

All routine blood tests were within normal limits, except for very mild leukocytosis. This mild presentation contrasts with the severe final pathologic diagnosis of mucinous appendiceal adenocarcinoma with perforation/fistulization. This discrepancy is explained by the pathological finding that the cancer at perforation formed a malignant appendiceal-to-sigmoid fistula that most likely contained the inflammation and prevented acute appendicitis after perforation, and helped locally contain the malignancy without distant malignant seeding and consequent development of distant metastases.

Abdomino-pelvic computed tomography revealed a dilated, heterogeneous, appendix with an 8-cm-long, ovoid, periappendiceal mass containing an appendix-to-sigmoid fistula, without evident pseudomyxoma peritonei or peritoneal spread. Abdomino-pelvic MRI showed on coronal view a dilated, 8-cm-long, fluid-filled, appendix fistulizing to the sigmoid; and showed on axial view an abnormally thick, enhancing, appendiceal wall without significant peri-appendiceal inflammation. These imaging tests, however, did not reveal the cause of the appendiceal fistulization. The differential diagnosis of the radiologic findings included most likely benign perforating appendicitis, and unlikely appendiceal malignancy with fistulization, including the rare malignancy of mucinous appendiceal adenocarcinoma.

Open laparotomy revealed an extensive mass involving appendix, cecum, sigmoid colon, anterior abdominal wall, and urinary bladder; no peritoneal implants, and no pseudomyxoma peritonei. The abdominal mass was removed en-bloc including resection of sigmoid colon, cecum (with preservation of ileocecal valve), appendix, right vas deferens, testicular vessels, and minimal amounts of anterior abdominal wall; and shaving off of small parts of the wall of the urinary bladder and small bowel. No chemotherapy or radiotherapy was administered postoperatively because pathologic examination revealed a bulky primary tumor with surgical margins clear of cancer, no involved lymph nodes, and no distant metastases or pseudomyxoma peritonei.

Gross pathological examination of the resected mass showed an appendix-to-sigmoid fistula, as confirmed by a probe, from prior perforation of a promontoric (preileal/postileal appendix traveling from cecal base towards the sigmoid in the pelvis). Microscopic pathology showed well-differentiated, invasive, mucinous, adenocarcinoma diffusely involving the appendix and adjacent mass. All surgical margins and all 13 lymph nodes in the resected specimen were devoid of cancer (Stage pT4b N0).

Mucinous appendiceal adenocarcinoma is a low-grade cancer that rarely metastasizes to distant organs, except for the ovaries in females. The relatively benign clinical presentation and clinical course during 1 year of follow-up is explained by the well-described indolent, nonaggressive, nature of this cancer, and the sigmoid fistulization after malignant perforation that likely prevented the acute clinical presentation of sepsis normally expected after free appendiceal perforation, and likely contained the spillage of cancer cells and prevented subsequent distant metastases. The finding of mucinous appendiceal carcinoma despite a normal appearing appendiceal orifice at colonoscopy 2 years earlier is pathophysiologically reasonable. Colonoscopy performed soon before the pathologic diagnosis of mucinous appendiceal adenocarcinoma usually does not reveal the cancer because only the appendiceal orifice is visualized at colonoscopy and cancer deep in the appendix is not visualized.

The key finding is the favorable clinical course and apparent cancer cure with negative surgical margins, no involved lymph nodes, and no pseudomyxoma peritonei at surgery and at 1-year follow-up, despite the malignant perforation and bulky primary cancer. This phenomenon is explained by the appendix-to-sigmoid fistula containing the spillage of cancerous cells within the colon and preventing free spillage and consequent distant metastases, by the low grade, nonaggressive nature of MAA, and perhaps by the adhesiveness of mucin which might have promoted fistulization.

This is an interesting presentation of a Case report with literature review in which is evaluated limited, local, extracolonic spread of mucinous appendiceal adenocarcinoma after perforation with formation of a malignant appendix-to-sigmoid fistula.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Garcia-Olmo D, Majbar MA, Ramanathan S, Zerem E S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Tan KK, Hong CC, Zhang J, Liu JZ, Sim R. Predictors of outcome following surgery in colonic perforation: an institution’s experience over 6 years. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:277-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nitecki SS, Wolff BG, Schlinkert R, Sarr MG. The natural history of surgically treated primary adenocarcinoma of the appendix. Ann Surg. 1994;219:51-57. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Gourgiotis S, Oikonomou C, Kollia P, Falidas E, Villias C. Persistent Coughing as the First Symptom of Primary Mucinous Appendiceal Adenocarcinoma. J Clin Med Res. 2015;7:649-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Topkan E, Polat Y, Karaoglu A. Primary mucinous adenocarcinoma of appendix treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy: a case report. Tumori. 2008;94:596-599. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2010;1089. |

| 6. | Behera PK, Rath PK, Panda R, Satpathi S, Behera R. Primary appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinoma. Indian J Surg. 2011;73:146-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ploenes T, Börner N, Kirkpatrick CJ, Heintz A. Neuroendocrine tumour, mucinous adenocarcinoma and signet-ring cell carcinoma of the appendix: three cases and review of literature. Indian J Surg. 2013;75:299-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sirintrapun SJ, Blackham AU, Russell G, Votanopoulos K, Stewart JH, Shen P, Levine EA, Geisinger KR, Bergman S. Significance of signet ring cells in high-grade mucinous adenocarcinoma of the peritoneum from appendiceal origin. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:1597-1604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hata K, Tanaka N, Nomura Y, Wada I, Nagawa H. Early appendiceal adenocarcinoma. A review of the literature with special reference to optimal surgical procedures. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:210-214. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Ito H, Osteen RT, Bleday R, Zinner MJ, Ashley SW, Whang EE. Appendiceal adenocarcinoma: long-term outcomes after surgical therapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:474-480. [PubMed] |

| 11. | McCusker ME, Coté TR, Clegg LX, Sobin LH. Primary malignant neoplasms of the appendix: a population-based study from the surveillance, epidemiology and end-results program, 1973-1998. Cancer. 2002;94:3307-3312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ramaswamy V. Pathology of Mucinous Appendiceal Tumors and Pseudomyxoma Peritonei. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2016;7:258-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Cerame MA. A 25-year review of adenocarcinoma of the appendix. A frequently perforating carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:145-150. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Ronnett BM, Zahn CM, Kurman RJ, Kass ME, Sugarbaker PH, Shmookler BM. Disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis and peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis. A clinicopathologic analysis of 109 cases with emphasis on distinguishing pathologic features, site of origin, prognosis, and relationship to “pseudomyxoma peritonei”. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1390-1408. [PubMed] |

| 15. | McGory ML, Maggard MA, Kang H, O’Connell JB, Ko CY. Malignancies of the appendix: beyond case series reports. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:2264-2271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sugarbaker PH. Managing the peritoneal surface component of gastrointestinal cancer. Part 2. Perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Oncology (Williston Park). 2004;18:207-219; discussion 220-222, 227-228, 230. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Kusamura S, Younan R, Baratti D, Costanzo P, Favaro M, Gavazzi C, Deraco M. Cytoreductive surgery followed by intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion: analysis of morbidity and mortality in 209 peritoneal surface malignancies treated with closed abdomen technique. Cancer. 2006;106:1144-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gusani NJ, Cho SW, Colovos C, Seo S, Franko J, Richard SD, Edwards RP, Brown CK, Holtzman MP, Zeh HJ. Aggressive surgical management of peritoneal carcinomatosis with low mortality in a high-volume tertiary cancer center. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:754-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wakeley CP. The Position of the Vermiform Appendix as Ascertained by an Analysis of 10,000 Cases. J Anat. 1933;67:277-283. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Ahmed I, Asgeirsson KS, Beckingham IJ, Lobo DN. The position of the vermiform appendix at laparoscopy. Surg Radiol Anat. 2007;29:165-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Trivedi AN, Levine EA, Mishra G. Adenocarcinoma of the appendix is rarely detected by colonoscopy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:668-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |