Published online Oct 14, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i38.8615

Peer-review started: April 26, 2016

First decision: June 20, 2016

Revised: July 6, 2016

Accepted: August 5, 2016

Article in press: August 5, 2016

Published online: October 14, 2016

Processing time: 170 Days and 12 Hours

To investigate the incidence of achalasia in Algeria and to determine its clinical and para-clinical profile. To evaluate the impact of continuing medical education (CME) on the incidence of this disease.

From 1990 to 2014, 1256 patients with achalasia were enrolled in this prospective study. A campaign of CME on diagnosis involving different regions of the country was conducted between 1999 and 2003. Annual incidence and prevalence were calculated by relating the number of diagnosed cases to 105 inhabitants. Each patient completed a standardized questionnaire, and underwent upper endoscopy, barium swallow and esophageal manometry. We systematically looked for Allgrove syndrome and familial achalasia.

The mean annual incidence raised from 0.04 (95%CI: 0.028-0.052) during the 1990s to 0.27/105 inhabitants/year (95%CI: 0.215-0.321) during the 2000s. The incidence of the disease was two and half times higher in the north and the center compared to the south of the country. One-hundred-and-twenty-nine (10%) were children and 97 (7.7%) had Allgrove syndrome. Familial achalasia was noted in 18 different families. Patients had dysphagia (99%), regurgitation (83%), chest pain (51%), heartburn 24.5% and weight loss (70%). The lower esophageal sphincter was hypertensive in 53% and hypotensive in 0.6%.

The mean incidence of achalasia in Algeria is at least 0.27/105 inhabitants. A good impact on the incidence of CME was noted. A gradient of incidence between different regions of the country was found. This variability is probably related to genetic and environmental factors. The discovery of an infantile achalasia must lead to looking for Allgrove syndrome and similar cases in the family.

Core tip: The exact incidence of achalasia is unknown. Few epidemiological studies around the world have been devoted to it. The impact of continuing medical education (CME) on incidence of achalasia has not been evaluated. This study showed that CME has a positive effect on the incidence of this disease. In fact, the mean incidence raised from 0.04 (95%CI: 0.028-0.052) during the 1990s to 0.27/105 inhabitants/year (95%CI: 0.215-0.321) during the 2000s. This incidence was two and half times higher in the north and the center compared to the south of the country. This variability is probably related to genetic and environmental factors.

- Citation: Tebaibia A, Boudjella MA, Boutarene D, Benmediouni F, Brahimi H, Oumnia N. Incidence, clinical features and para-clinical findings of achalasia in Algeria: Experience of 25 years. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(38): 8615-8623

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i38/8615.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i38.8615

Achalasia is a primary esophageal motility disorder characterized by esophageal aperistalsis and failure of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) to relax normally with swallowing. It is self-secondary to a degeneration of the myenteric plexus[1,2]. Its etiology remains, to date, unknown. However, the existence of family cases, most often falling under Allgrove syndrome, suggests the existence of genetic factors predisposing to this condition. Infectious and auto-immune processes have also been postulated[3,4].

Achalasia is a motility disorder that can occur at any age, from newborns to the elderly. The revealing symptoms are aspecific, such as dysphagia, chest pain, regurgitation, weight loss, and rarely pulmonary complications. The diagnosis is based on esophageal manometry (EM) results, noticed during swallowing[5]. Few epidemiological studies around the world have been devoted to it. Most of them were carried out in Western countries and showed that it is a rare condition. The mean prevalence and incidence worldwide have been estimated as 10/105 and 1/105 inhabitants respectively[6]. No study assessing the characteristics of achalasia in Algeria, an African and Mediterranean country, has been published so far.

This work aims to evaluate the incidence and prevalence of achalasia, and to study its clinical and para-clinical features in this country.

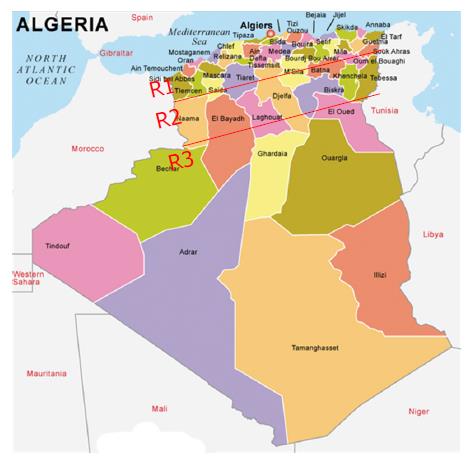

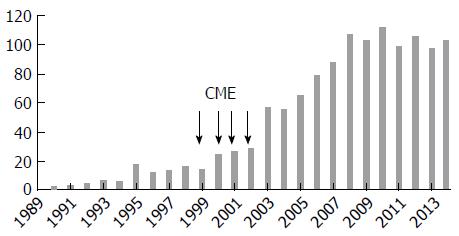

In this prospective study, 1256 patients [653 (52%) females and 603 (48%) males; mean age: 43.3 ±18.7 years (3 mo-86 years)] with achalasia were enrolled over a period of 25 years, from 1990 to 2014, from among the 106795 patients investigated by upper endoscopy for various purposes. The patients were grouped based on their geographical origin, among three regions (Figure 1). Region 1 included coastal and center cities, characterized by a Mediterranean climate and a diet based on fruits, vegetables and cereals (14 cities; number of inhabitants: 12689307). Region 2 included the highlands cities, characterized by a dry climate and a diet based on cereals and vegetables (22 cities; number of inhabitants: 15501671). Region 3 included the Southern cities adjacent to the sub-Saharan Africa, characterized by hot climate and a diet based on dates, meat and cereals (12 cities; number of inhabitants: 3870697). This work was funded by the Ministries of Health and of Higher Education. Continuing medical education (CME) campaigns were conducted between 1999 and 2003 in different regions of the country (Figures 1 and 2). It focused on the clinical manifestations of the disease, particularly in the interest of EM to confirm diagnosis and provide information to both general practitioners and specialists that our department is the reference center in the management of achalasia, as well.

This study was carried out following two steps at our institution, which is the national reference center in Algeria regarding the management of esophageal motility disorders. Along the first step, from 1990 to 1998, the disease was largely unknown in Algeria and during the second step, from 1999 to 2014, the disease was more familiar to practitioners through CME campaigns.

A standardized questionnaire clarified the geographical origin, the number of consultations before achalasia was diagnosed, the history of symptoms and their nature, as well as their severity. Dysphagia, regurgitation and chest pain were scored from 0 to 3, based on their frequency, but weight loss was scored based on its severity from 0 to 3, as well. We also systematically looked for heartburn and respiratory events (i.e. cough, dyspnea, asthma), familial achalasia and Allgrove syndrome.

Esophageal barium swallow: The diagnosis of achalasia was suspected in the presence of at least one of the following radiological signs: regular narrowing of the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ), slightly extended in “bird’s beak” and/or dilatation of the esophageal body (EB) with absence of contractions. This dilatation was classified into four stages defined according to the diameter of the esophagus.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy: Endoscopy was performed by four senior doctors aiming to look for signs in favor of achalasia and complications such as esophagitis, esophageal candidiasis or an over-cardial diverticulum. It was also intended to eliminate other causes of stenosis of GEJ (i.e., neoplasm, peptic stenosis).

EM: EM was carried out using an Arndorfer pneumo-hydraulic perfusion system with a low compliance capillary infusion, connected to a polygraph. Patients had to fast for at least 12 h. Stopping all drugs that can act on esophageal motility was systematically recommended.

The probe was nasally introduced until the side holes of the 4 sensors were placed in the stomach. The probe was then progressively removed from the stomach, cm by cm, with identification of the LES on the recorded graph at each of the 4 channels in order to calculate the length and the mean basal pressure of the LES. The esophageal motility was studied by performing 10 water swallows spaced at least 30 s apart. Classic achalasia diagnosis was made when a total aperistalsis was noticed (100% of non-peristaltic waves) associated or not with an increased LES tone (> 34 mm Hg) and/or a LES failure to relax (< 80% of the basal pressure), with absence of any organic barrier at the GEJ. The diagnosis of vigorous achalasia was made when aperistalsis was associated to an amplitude contraction wave ≥ 40 mm Hg.

Diagnosis criteria of Allgrove syndrome and familial achalasia: Allgrove syndrome diagnosis was made when at least 2 out of the 3 following signs were present: achalasia, Alacrima, adrenal insufficiency.

Familial achalasia diagnosis was established when at least 2 members of one family had achalasia, whether it was isolated (sporadic achalasia) or fell under Allgrove syndrome (syndromic achalasia). Consanguinity, defined as first- or second-cousin marriages, was systematically looked for.

Exclusion criteria: Other esophageal motility disorders, collagen diseases, prior esogastric surgeries, eosinophilic esophagitis and tumors of GEJ were excluded.

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software version 17.0. Annual incidence of achalasia was calculated by relating the number of diagnosed cases to 105 inhabitants, based on a population reported annually by the National Office of Statistics in Algeria (ONS; web: http://www.ons.dz). Quantitative variables were expressed in gross figures, proportions and rates. Rates of different results have been calculated with their 95%CI. Differences between proportions were calculated using χ2 and the P value was considered significant when it was lower than 0.05.

Comparison of the achalasia different means incidence, delay diagnosis means and age at diagnosis corresponding to the three periods of 1990-1997, 1998-2005 and 2006-2014 was performed through a variance analysis. Comparison of the achalasia different means incidence corresponding to the different regions in Algeria (north, highlands and south) was made, as well.

Our study included 1256 patients from the 48 Wilayas (provinces) of the country (Figure 1). The average age at diagnosis was 45 years (95%CI: 38.0-52.0) during the first period, 40.7 years (95%CI: 38.6-42.9) during the second one and 40.3 (95%CI: 39.0-41.6) between 2006 and 2014, but the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

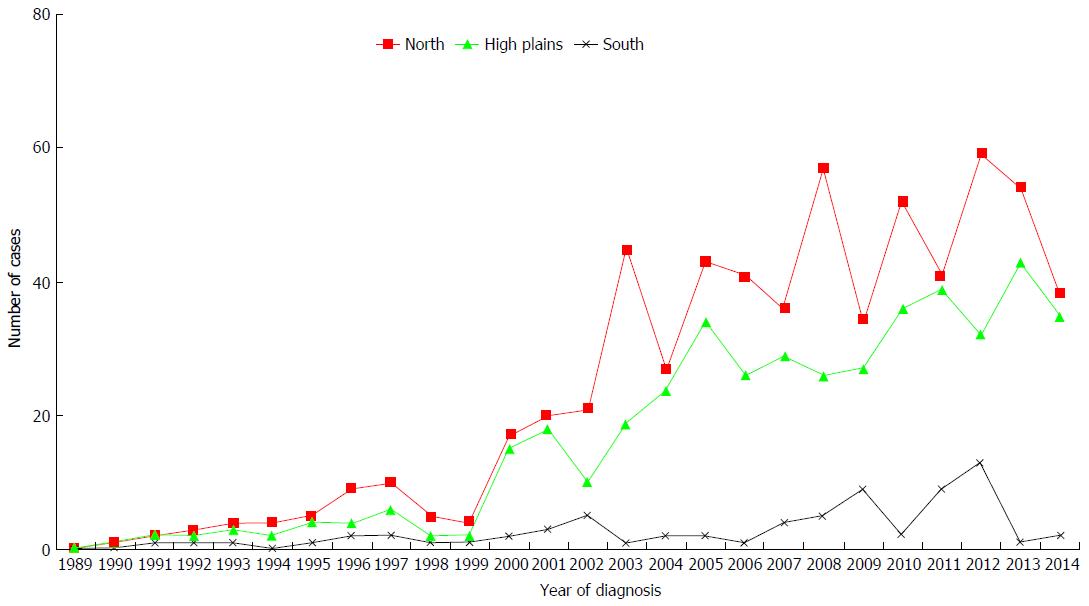

The number of cases diagnosed each year is shown in Figures 2 and 3. The average number of new cases of achalasia diagnosed per year during periods from 1990 to 1997, 1998 to 2005 and 2006 to 2014 was respectively 10, 34.3 and 99.4 cases. The mean annual incidence from 1990 to 1997 was of 0.04 patients/year/105 inhabitants. From 1998 to 2005, it increased to 0.1 patients/year/105 inhabitants to reach a rate of 0.27 patients/year/105 inhabitants from 2006 to 2014 (P < 0.001) (Table 1). The prevalence of achalasia in Algeria during 2014 has been estimated to 3.2 patients/105 inhabitants (1256/39928947). More interesting, the incidence in regions 1 and 2 were three times more important when compared to region 3 (Table 2): 0.21 patients/year/105 inhabitants vs 0.12 vs 0.07 (P < 0.001).

| Year interval | Mid-period population | Cases, n | Mean incidence, (cases/105 inhabitants/yr) | 95%CI |

| 1990-1997 | 28385621 | 87 | 0.04 | 0.028-0.025 |

| 1998-2005 | 32370618 | 274 | 0.108 | 0.072-0.144 |

| 2006-2014 | 37128618 | 895 | 0.268 | 0.215-0.321 |

| Regions of country | Mid-period population 1990 to 2014 (2002) | Cases, n | Cases/105 habitants/yr | 95%CI |

| R1 North | 12689307 | 693 | 0.2184 | 0.1811-0.2501 |

| R2 High plains | 15501671 | 488 | 0.1256 | 0.0921-0.1536 |

| R3 South | 3870607 | 75 | 0.0772 | 0.0432-0.1121 |

The average number of consultations that preceded the diagnosis of achalasia was 6 ± 8.7 (range: 3 to 21 consultations).

The mean delay diagnosis of achalasia from 1990 to 1997 was 75.78 mo (95%CI: 50.93-100.63). From 1998 to 2005, it dropped to 54.68 mo (95%CI: 45.39-63.97) to reach a mean of 48.76 mo (95%CI: 43.22-54.30) from 2006 to 2014. However, this difference was not significant between the three periods (P > 0.05). Allgrove syndrome was noted in 97/1256 (7.7%) patients [female (53%); mean age: 16.23 ± 10.4; range: 8 mo-41 years]. It was a 3A syndrome in 46.4% (45/97) of cases, a 2A syndrome in 25.7% (25/97) of cases and a 4A syndrome in 27.8% (27/97) of cases. Consanguinity was found in 63% (61/97) of cases. It always included a neonatal alacrima while respective rates of achalasia, adrenal insufficiency, neurological abnormalities were 100% (97/97), 46% (45/97) and 52.6% (51/97). There was a familial achalasia in 41 patients belonging to 18 different families. It was a syndromic achalasia in 34/41 belonging to 15/18 families. Achalasia was sporadic in 7/41 (17%) other patients from 3/18 remaining families. The average number of subjects affected by family was 2.26 (range: 2-4). All familial achalasia cases were observed in siblings (brothers and sisters). No case of parent/child achalasia has been recorded. Among children, classic and familial syndromic achalasia were noted in respectively 55% (71/129) and 45% (58/129) of cases.

Dysphagia was observed in 1243/1256 (98.9%) patients and regurgitation in 1042/1256 (83%) patients. Retro-sternal, epigastric or inter-scapulars pain were noted in 640/1243 (51%) patients. They preceded dysphagia of several months [average: 23 ± 14 mo (6-36) mo] in 2.5% (32/1256) of patients. Weight loss was present in 879 (70%) patients. The mean weight loss was 9.5 ± 7 kg (range: 1-40 kg). Heartburn was noticed in 308/1256 patients (24.5%) and respiratory symptoms were present in 280/1256 (22.3%) patients. Nocturnal cough, effort dyspnea and recurrent bronchial infections were noted in respectively 14.5% (182/1256), 5% (63/1256) and 2% (25/1256) of cases. More rarely, it was a genuine bronchial asthma in 12/1256 (0.9%). Pulmonary banal germ abscess, pulmonary tuberculosis and a mediastinal syndrome were noted in respectively 0.3% (4/1256), 0.16% (2/1256) and 0.3% (4/1256) of cases (Table 3).

| Female/male | 653 (52)/603 (48) |

| Age | 43.3 ± 18.7 yr (3 mo-86 yr) |

| Adult/children | 1127 (89)/129 (10.3) |

| Non-syndromic achalasia/syndromic achalasia | 1153/97 |

| Familial achalasia (18) | 41 |

| Syndromic achalasia | 34 |

| Sporadic (isolated) achalasia | 7 |

| Duration of symptoms (mo) | 59.5 (2-480) |

| Dysphagia | 1243 (99) |

| Regurgitation | 1042 (83) |

| Chest pain | 690 (55) |

| Weight loss | 879 (70) |

| Mean weight loss (kg) | 7 ± 5.9 (1-40) |

| Heartburn | 308 (24.5) |

| Respiratory manifestations | 280 (22.3) |

Esophageal barium swallow was performed in 95% (1193/1256) of patients. It allowed note of a typical aspect of bird’s beak stenosis in 87% (1037/1193) of cases and a dilatation of the EB in 95% (1193/1256) of cases. The mean esophageal diameter was 5.8 ± 4.3 cm (95%CI: 1.9-8.5). The respective rates of stages 0, I, II and III of dilatation were 6%, 28%, 42% and 24%.

Endoscopy was pathological in 85% (1067/1256) of cases. A popping effect, a fluid stasis and the EB dilation aspect were observed respectively in 47% and 53% of cases. The popping effect was isolated in 414/1256 (33%) patients, whereas the fluid stasis was always associated to an EB dilation aspect. Esophageal candidiasis and stasis esophagitis were noted respectively in 6% (75/1256) and 0.4% (5/1256) of cases.

Manometry was performed in 1186 patients and the LES pressure (LESP) was specified in 76% (954/1256) cases. A failure of the probe passage through the cardia, due to an EB tortuosity or an absence of LES opening, was observed in 24% (302/1256) of patients. The mean LESP was 32.17 ± 15 mmHg. The LES was normotensive in 47% (448/954), hypertensive in 53% (505/954) of patients and hypotensive in 0.6% (6/954) of cases.

Incomplete or absent LES relaxation was noted in 98% (934/954) of cases. Relaxation rate ranged from 0% to 25% in 383/954 (40%) patients, from 26% to 50% in 327/954 patients (34%) and from 52 to 80% in 196/954 (20.5%) patients. Esophageal peristalsis was evaluated in 94.4% (1186/1256) of patients. An extended aperistalsis to the whole EB was constant. Vigorous achalasia was noted in 26% (308/1186) of cases. The average amplitude of the contractile wave was 20.78 ± 18.67 (95%CI: 0-37) mmHg in the classic achalasia group and 57 ± 19 (range: 40-134 mmHg) in the vigorous achalasia group. The esophageal basal pressure was studied in 277 patients. It was always positive with a mean value of 4.7 ± 5 mmHg (range: 0-18) (Tables 4, and 5).

| Bird's beak aspect | 1037 (87) |

| Mean esophageal diameter (cm), mean ± SD | 5.8 ± 4.3 |

| ≤ 2 cm (normal) | 60 (5) |

| 2-4 | 334 (28) |

| 4-6 | 513 (43) |

| 6-9 | 286 (24) |

| Hiatal hernia | 6 |

| Epiphrenic diverticula | 2 |

| LES pressure (mmHg) | 954 (76); mean: 32 ± 15 (10-87) |

| 12-24 | 257 (27) |

| 24-34 | 192 (20) |

| > 34 | 504 (53.5) |

| < 12 | 2 (0.6) |

| LES relaxation | 1130 (90) |

| Absent | 46% |

| Incomplete | 56% |

| EAC mean (mmHg) | 1186 (94.5) 26.78 ± 19.67 |

| (0-134) | |

| Classic achalasia (mmHg) | 20.78 ± 18.76 (0-37) |

| Vigorous achalasia | 57 ± 19 (40-134) |

Data concerning the epidemiology of achalasia in Africa are lacking, and the epidemiology of the disease in Algeria has never been studied. To our knowledge, this is the first study of achalasia in our country. This prospective study focused on a large series of 1256 patients with achalasia, from the 48 provinces of Algeria. This is a homogenous and representative sample of Algerian population, from which it was possible to estimate, for a period of 25 years, the incidence of this disease in Algeria and to study its clinical and para-clinical features. Our work has shown that the average annual incidence of achalasia has followed an upward curve during the different periods of the study. Indeed, it increased from 0.04/105 inhabitants/year during 1990-1997 to 0.27/105 inhabitants/year from 2008 to 2014.

The few studies[6-12] that have investigated the epidemiology of this disease worldwide, mostly carried out in Western countries, showed that the annual incidence of achalasia varies between 0.55 and 1.63/105 inhabitants, 2 to 5 times higher rates compared to those noted in our study and those of the two Asian series[11,12]. The same trend was noted with the prevalence results, their values ranged from 7.1/105 inhabitants to 13.4/105 inhabitants in Western countries[10] and between 1.77/105 and 6.29/105 inhabitants in Asia and Algeria (3.14 patients/105 inhabitants).

All these studies conclude that achalasia is a rare condition; the prevalence is probably underestimated because many physicians are inadequately familiar with the clinical picture of achalasia. This approach is supported probably by the very likely impact that the awareness campaign had on the increase of the annual incidence of achalasia in Algeria. This condition is even rarer in black African patients or those living in the tropics. Actually, both series published on black patients - the SILBER series in South Africa[13], which enrolled 26 cases in 10 years, and the STEIN[14] series in Zimbabwe, which reported 25 cases between 1974 and 1983 - suggest that the incidence of achalasia in sub-Saharan Africa is 0.003/105 inhabitants/year. Thus, this motility disorder is 10 times less common in these countries compared to Western countries.

However, the low number of works that have been devoted to it and the lack of diagnostic facilities in these regions of the world suggest that the exact frequency of this disorder is probably underestimated in these regions.

In our study, we found a gradient between different regions of the country. The incidence of the disease was two and half times higher in the north and the center compared to the south (0.196 vs 0.116 vs 0.062). These regions have ethnic (predominance of black patients at the south of the country), climatic and food differences. We believe that the incidence of achalasia is underestimated in Algeria, especially in the south, because of many factors, one of them being the limited access to our institution due to distance and possibly to socio-economic status and the quality of medical coverage. In the United States, various epidemiological studies carried out in the country showed no achalasia incidence differences between black people and those with white skin[15,16]. Thus, this variability in incidence between races, different regions in the world and different regions of a same country, implies, as has been suggested by some authors, the existence of environmental and genetic factors responsible for the occurrence of the disease[17-19]. Achalasia affects both sexes with equal rate[20] as shown in our study. The mean age of diagnosis of this motility disorder which affects adults in most cases in Western series, varies between 46-years-old and 66-years-old, with two peaks of incidence in the third and seventh decade of life [15,18,21].

In our study, patients were relatively younger; whereas the mean diagnosis period was 59.7 mo, ranging from 2 mo to 480 mo. This diagnosis latency is probably due to aspecific symptoms that may delay the condition diagnosis investigation[22]. To our knowledge, the diagnosis period (mean delay diagnosis) and age at diagnosis have never been studied on such an important series. In this work, we noticed that both of them have been improved during the three periods. This trend is probably related to the awareness campaign, conducted regularly from 1999 as a CME, in different regions of the country. Further studies are required in other countries with a larger population to confirm these results.

The frequency of clinical signs varies depending on the studied symptom and series[5,16].

Dysphagia is almost constant (82%-100%), while a large variability between series characterizes regurgitation (56%-97%), weight loss (30%-91%), chest pain (17%-95%) and heartburn (27%-42%). The same results were found in our series. One of the most interesting clinical aspects of this study is to have shown that chest pain preceded dysphagia by several months (mean: 23 ± 14 mo) in 5% of patients. This misleading clinical presentation of this affection in our series is probably one of the causes of delayed diagnosis, since patients were initially oriented to cardiology looking for a coronary disease. Broncho-pulmonary signs, noted in 11% to 46% of cases, may also be the cause of delayed diagnosis because they usually lead patients to pneumology consultation first[23].

The diagnosis of achalasia relies on EM[24,25]. However, this procedure, which is available only in reference centers in low-incomes countries, is not performed as first-line. It is preceded, due to the nature of revealing signs as dysphagia and regurgitation, by barium swallow and upper endoscopy to fully exclude inflammatory or structural lesions.

The benefit of manometry is particularly important when the barium swallow and endoscopy do not reveal abnormalities[26]. EB aperistalsis, constant in our study, is the only manometric cardinal feature that leads to achalasia diagnosis. It is characterized in most cases by simultaneous or undefined esophageal contractions of very low amplitude, thus realizing the aspect of classical manometric achalasia.

Achalasia is considered vigorous when the mean amplitude threshold is more than 37 mmHg[27]. This form, which still subject of controversy as to its individualization as a separate entity from classic achalasia[28], would in fact correspond to an early disease stage characterized by a high amplitude contractions of the EB with intense retro-sternal pain. In our experience, vigorous achalasia remains a rare situation that presents no clinical or manometric feature compared to classic achalasia.

For a long time, LES hypertonia was considered as essential for achalasia diagnosis, while LES hypotonia was described as incompatible with the diagnosis of untreated achalasia[25,29]; its presence should instead lead to scleroderma diagnosis or gastroesophageal reflux disease.

In fact, some authors recently reported that LES hypertonia was present in only 42% of patients while hypotonia was noted in 25% of them[30]. Our work has also shown that LES hypertonia was inconstant, being observed in only 53% of patients while hypotonia was very rare. More constant is the LES relaxation defect, which was found in 98% of patients, the association with esophageal aperistalsis is highly suggestive of this condition’s diagnosis. If LES is manometrically normal, the diagnosis of achalasia should rely on the confrontation of manometric, clinical, radiological and endoscopic data.

The few studies that have been devoted to children show that achalasia is even infrequent in this age group compared to adults. Pediatric achalasia represents only 4% to 5% of all achalasia diagnosed worldwide and 10% of those included in our study. The incidence in this group age is estimated between 0.1-0.18/105 children/year[31,32].

At the family level, our study showed that, infantile achalasia can take many forms. It may be a non-familial isolated classic achalasia, a sporadic Allgrove syndrome, a familial achalasia without Allgrove syndrome or a familial Allgrove syndrome. In this work, the respective prevalence of familial and non-familial forms in children achalasia was 45% and 55%.

These results, which show a high rate of family forms, are most probably related to the widespread tradition of consanguineous marriage in Algeria. Infantile achalasia must systematically lead to seeking of similar cases in the family and other signs of Allgrove syndrome. This syndrome is a very rare genetic autosomal recessive disorder, and its occurrence is favored by consanguineous marriages.

The AAAS gene responsible for this disease is carried by the long arm of chromosome 12 (12q13) and contains 16 exons. Mutations of this gene which were currently implicated are the IVS14, most common mutation, and EVS9. These mutations were identified for the first time in 2000 by Tullio-Pelet et al[33] in a study that gathered 7 of the 18 Algerian families included in this study, 3 Tunisian families, and a sing Turkish, French and Spanish family each. The few studies that have tackled familial achalasia reported that 1/3 of children were from consanguineous marriages, whereas parent/children transmission was very rare or exceptional[34,35].

In summary, achalasia is a rare disorder, the worldwide frequency of which, most probably underestimated, varies depending on countries. This variability is probably related to genetic and environmental factors. In Algeria, the incidence of the disease is at least 0.27/105 inhabitants. This motility disorder sometimes raises the difficulty of its delayed diagnosis due to its aspecific revealing signs. However, in this study there is suggestion that CME improved (reduced) the delay diagnosis, age at diagnosis and increased the incidence of achalasia. The diagnosis is evident when EM shows EB aperistalsis associated to LES hypertonia. When hypertonia is absent, achalasia diagnosis should rely on a confrontation of manometry, barium swallow and upper endoscopy data. Finally, the discovery of an infantile achalasia must systematically lead to looking for Allgrove syndrome and similar cases in the family.

We are indebted to the patients for their invaluable cooperation and we recognize our master, the deceased Professor Brahim Touchene.

There is a lack of epidemiological data of achalasia and Allgrove syndrome in Algeria. The impact of continuing medical education (CME) on incidence of achalasia has not been evaluated. The current study was designed to investigate the incidence of achalasia and to evaluate the impact of CME on the incidence of this disease.

For some authors, the incidence of achalasia is increasing and environmental factors have been implicated. But, few epidemiological studies around the world have been devoted to it.

This large prospective study has shown that the incidence in Algeria is at last 0.27/105 inhabitants/year. The incidence of achalasia is increasing and there is a variability according to different regions in the same country. This variability is probably due to genetic and environmental factors. There is positive impact of CME on the incidence of achalasia.

This study serves as additional evidence supporting the investigation of the potential role of the environmental factors in increasing of the incidence of achalasia. The potential of CME in increasing incidence and possibly reducing the delay and age at diagnosis of achalasia is paramount.

This paper reports a very large experience, including very pertinent, meticulously collected clinical information over a period of 25 years, and is well written overall.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Algeria

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Frechette E, Kuribayashi S, Garcia-Olmo D S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Filipodiia E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Gockel HR, Schumacher J, Gockel I, Lang H, Haaf T, Nöthen MM. Achalasia: will genetic studies provide insights? Hum Genet. 2010;128:353-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Park W, Vaezi MF. Etiology and pathogenesis of achalasia: the current understanding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1404-1414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bosher LP, Shaw A. Achalasia in siblings. Clinical and genetic aspects. Am J Dis Child. 1981;135:709-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Annese V, Napolitano G, Minervini MM, Perri F, Ciavarella G, Di Giorgio G, Andriulli A. Family occurrence of achalasia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20:329-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Vaezi MF, Richter JE. Current therapies for achalasia: comparison and efficacy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:21-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mayberry JF. Epidemiology and demographics of achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:235-248, v. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Sadowski DC, Ackah F, Jiang B, Svenson LW. Achalasia: incidence, prevalence and survival. A population-based study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:e256-e261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Birgisson S, Richter JE. Achalasia in Iceland, 1952-2002: an epidemiologic study. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1855-1860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mayberry JF, Atkinson M. Variations in the prevalence of achalasia in Great Britain and Ireland: an epidemiological study based on hospital admissions. Q J Med. 1987;62:67-74. [PubMed] |

| 10. | O’Neill OM, Johnston BT, Coleman HG. Achalasia: a review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5806-5812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ho KY, Tay HH, Kang JY. A prospective study of the clinical features, manometric findings, incidence and prevalence of achalasia in Singapore. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:791-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim E, Lee H, Jung HK, Lee KJ. Achalasia in Korea: an epidemiologic study using a national healthcare database. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29:576-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Silber W. The prevalence, course and management of some benign oesophageal diseases in the Black population. The Groote Schuur Hospital experience. S Afr Med J. 1983;63:957-959. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Stein CM, Gelfand M, Taylor HG. Achalasia in Zimbabwean blacks. S Afr Med J. 1985;67:261-262. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Enestvedt BK, Williams JL, Sonnenberg A. Epidemiology and practice patterns of achalasia in a large multi-centre database. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1209-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Birgisson S, Richter JE. Achalasia: what’s new in diagnosis and treatment? Dig Dis. 1997;15 Suppl 1:1-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mayberry JF, Atkinson M. Incidence of achalasia in New Zealand, 1980-1984. An epidemiological study based on hospital discharges. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1988;3:247-257. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Farrukh A, Mayberry JF. Medico-legal significance of service difficulties and clinical errors in the management of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Med Leg J. 2015;83:29-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chuah SK, Hsu PI, Wu KL, Wu DC, Tai WC, Changchien CS. 2011 update on esophageal achalasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1573-1578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mikaeli J, Islami F, Malekzadeh R. Achalasia: a review of Western and Iranian experiences. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5000-5009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Podas T, Eaden J, Mayberry M, Mayberry J. Achalasia: a critical review of epidemiological studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2345-2347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Eckardt VF, Köhne U, Junginger T, Westermeier T. Risk factors for diagnostic delay in achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:580-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Eckardt VF, Stauf B, Bernhard G. Chest pain in achalasia: patient characteristics and clinical course. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1300-1304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hirano I, Tatum RP, Shi G, Sang Q, Joehl RJ, Kahrilas PJ. Manometric heterogeneity in patients with idiopathic achalasia. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:789-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Spechler SJ, Castell DO. Classification of oesophageal motility abnormalities. Gut. 2001;49:145-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 499] [Cited by in RCA: 466] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Howard PJ, Maher L, Pryde A, Cameron EW, Heading RC. Five year prospective study of the incidence, clinical features, and diagnosis of achalasia in Edinburgh. Gut. 1992;33:1011-1015. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Todorczuk JR, Aliperti G, Staiano A, Clouse RE. Reevaluation of manometric criteria for vigorous achalasia. Is this a distinct clinical disorder? Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:274-278. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Camacho-Lobato L, Katz PO, Eveland J, Vela M, Castell DO. Vigorous achalasia: original description requires minor change. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:375-377. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Vantrappen G, Hellemans J. Treatment of achalasia and related motor disorders. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:144-154. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Fisichella PM, Raz D, Palazzo F, Niponmick I, Patti MG. Clinical, radiological, and manometric profile in 145 patients with untreated achalasia. World J Surg. 2008;32:1974-1979. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Smits M, van Lennep M, Vrijlandt R, Benninga M, Oors J, Houwen R, Kokke F, van der Zee D, Escher J, van den Neucker A. Pediatric Achalasia in the Netherlands: Incidence, Clinical Course, and Quality of Life. J Pediatr. 2016;169:110-115.e3. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Marlais M, Fishman JR, Fell JM, Haddad MJ, Rawat DJ. UK incidence of achalasia: an 11-year national epidemiological study. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:192-194. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Tullio-Pelet A, Salomon R, Hadj-Rabia S, Mugnier C, de Laet MH, Chaouachi B, Bakiri F, Brottier P, Cattolico L, Penet C. Mutant WD-repeat protein in triple-A syndrome. Nat Genet. 2000;26:332-335. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Zimmerman FH, Rosensweig NS. Achalasia in a father and son. Am J Gastroenterol. 1984;79:506-508. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Torab FC, Hamchou M, Ionescu G, Al-Salem AH. Familial achalasia in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2012;28:1229-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |