Published online Sep 28, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i36.8234

Peer-review started: May 2, 2016

First decision: June 20, 201

Revised: July 7, 2016

Accepted: July 31, 2016

Article in press: August 1, 2016

Published online: September 28, 2016

Processing time: 146 Days and 10.2 Hours

Amebiasis is uncommon in developed countries. Several case reports in the literature emphasize that both the presenting symptoms and the radiological findings of colonic amebiasis closely resemble more common conditions, such as idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease and gastro-intestinal malignancy. We describe a unique case of colonic amebiasis (amebomas) coexisting with signet-ring cell carcinoma of the ileocecal valve, the cecum and the appendix. Endoscopically, the ulcerated tumor was indistinguishable from the ulcerations and pseudotumors (amebomas) detected in the ascending colon. Histological examination of biopsy specimens revealed the pathognomonic features of protozoa with ingested erythrocytes in combination with signet-ring cell infiltration. The author concludes that amebiasis may not only mimic carcinoma but, rarely, may coexist with carcinoma in the same patient. Clinicians and pathologists should be aware of this possibility in order not to delay diagnosis and treatment of malignant disease.

Core tip: This case report presents the unique case of a patient in whom colonic amebiasis (amebomas) and signet-ring cell carcinoma of the ileocecal valve, the cecum and the appendix were diagnosed in intestinal biopsy specimens. In the setting of amebiasis, malignancy may easily be overlooked. Therefore, clinicians and pathologists should be aware that colonic amebiasis and colorectal carcinoma may coexist in the same patient.

- Citation: Grosse A. Diagnosis of colonic amebiasis and coexisting signet-ring cell carcinoma in intestinal biopsy. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(36): 8234-8241

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i36/8234.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i36.8234

Amebiasis caused by Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) is one of the most fatal parasitic diseases worldwide. The organism is commonly acquired by ingestion of contaminated food and water and is endemic in developing countries with poor sanitation. Presentation of intestinal disease ranges from asymptomatic infection or acute proctocolitis to acute fulminant colitis with high mortality rates. Both the clinical presentation and the endoscopic appearance of colonic amebiasis can mimic colon carcinoma[1-8]. We present an exceedingly rare case of colonic amebiasis (amebomas) with coexisting signet-ring cell carcinoma of the ileocecal valve, the cecum and the appendix diagnosed upon histological and immunohistochemical examination of intestinal biopsy specimens.

A 35-year-old woman presented to our hospital with diarrhea, right-lower-quadrant abdominal pain and cramps of two months’ duration. The patient gave a travel history to Nepal where she had studied for one year prior to presentation. Her medical history was otherwise unremarkable; in particular, she had no family history of chronic idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease.

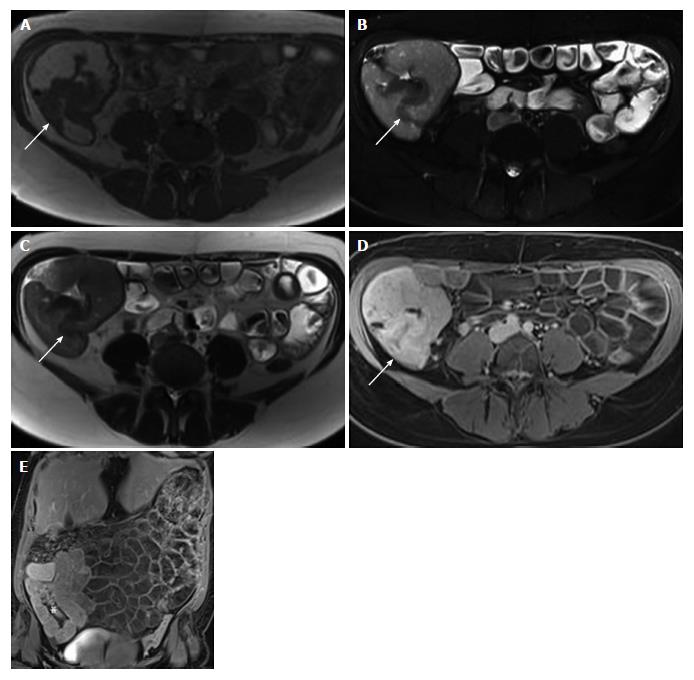

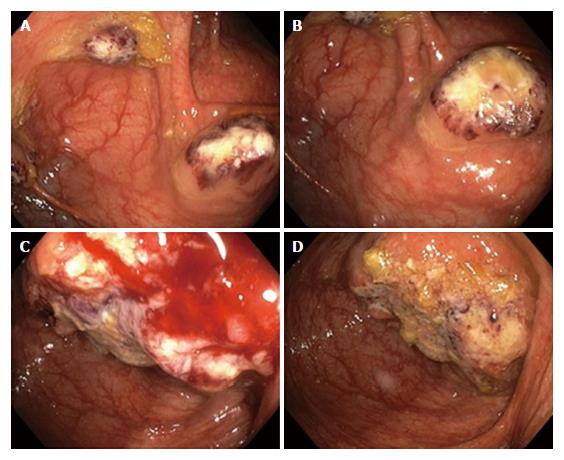

Laboratory tests revealed normocytic anemia (hemoglobin 105 g/L, hematocrit 0.34 L/L, and erythrocytes 3.70 T/L), with low vitamin B-12 (130 ng/L), high serum iron (35.3 μmol/L), significantly increased serum ferritin (1042 μg/L) and normal transferrin, as well as neutrophilic leukocytosis (leukocytes 11.52 G/L and neutrophils 9.30 G/L). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed mural thickening of the ileocecum and the appendix, which was interpreted as being inflammatory in nature (Figure 1); there was no evidence of an abscess. MRI also disclosed a nonhomogeneous, cystic mass of the left ovary that measured 7.9 cm in diameter. Gastroscopy and proctoscopy including anorectal examination were inconspicuous. Colonoscopy revealed multiple ulcerations and up to 10 well-circumscribed, ulcerated, tumor-like masses, separated by normal mucosa, in the ascending colon (Figure 2A and B). The masses were livid-colored at the periphery and necrotic at the center, and these masses ranged in size from 8 mm to 33 mm in diameter. A similar, but larger (4.5 cm in diameter) and more solid lesion was found at the ileocecal valve involving the adjacent cecum and the appendix (Figure 2C and D). These endoscopic manifestations were considered to be inconclusive. While the ulcerated lesions were found to be atypical of Crohn’s disease, differential diagnoses included tuberculosis, lymphoma and carcinoma.

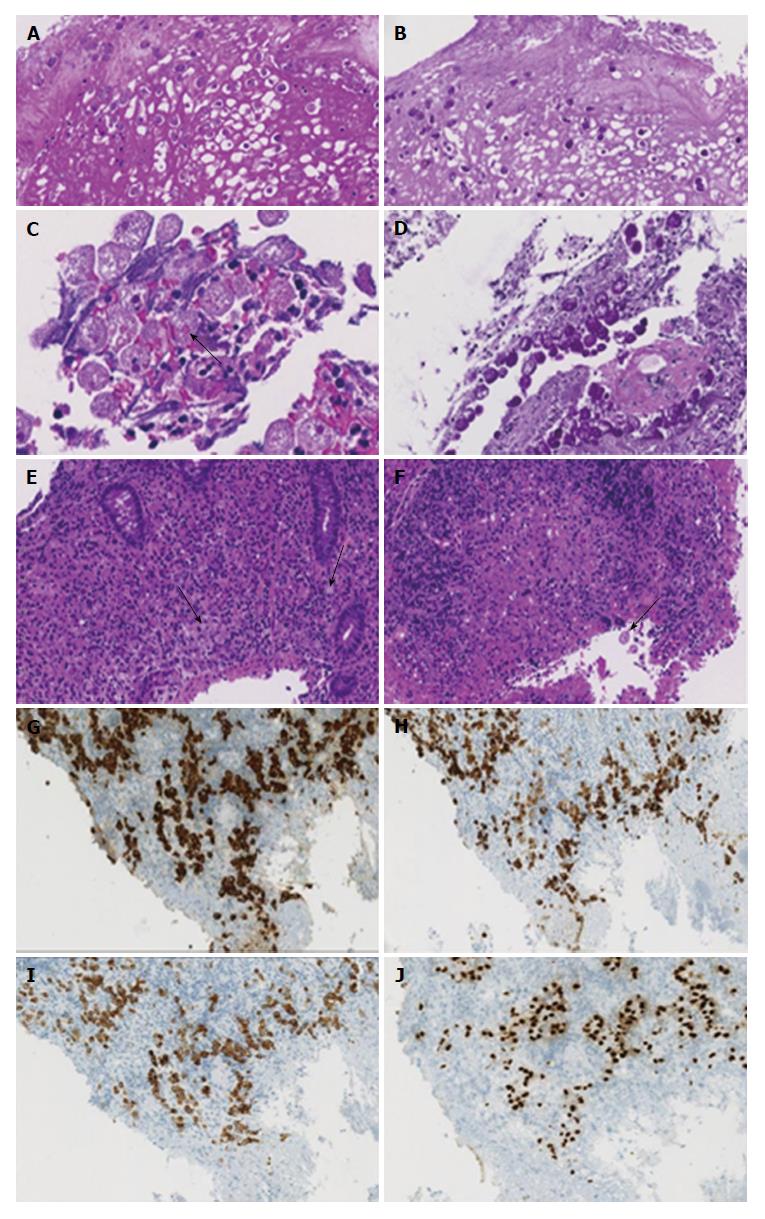

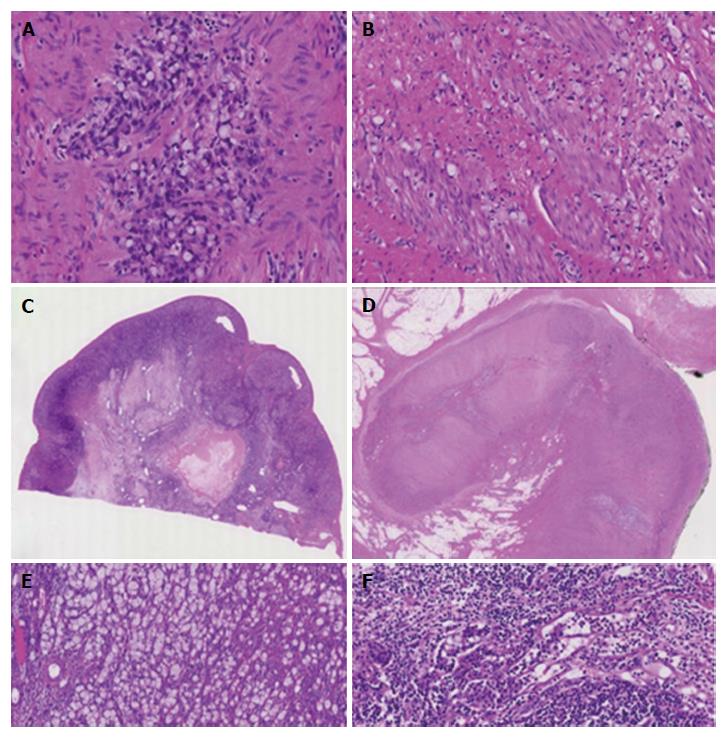

Microscopically, the masses in the ascending colon consisted of necrosis with large amounts of cell debris, desquamated epithelial cells and neutrophils, and extensive inflammatory tissue reaction in the absence of malignancy. Both in the debris and in the submucosal tissues there was evidence of periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive amebas that displayed characteristic features of the invasive pathogen with ingested erythrocytes (Figure 3A-D). Because of the absence of malignancy, the masses in the ascending colon were considered to be amebomas, a complication of chronic amebic disease. Microscopic examination (hematoxylin-eosin and immunohistochemical stains) of biopsy specimens from the ileocecal valve showed amebas intermixed with signet-ring cells infiltrating the submucosa (Figure 3E-J). The CK 7, CK 20 and CDX-2 positive tumor cells, which stained negative with neuroendocrine markers, demonstrated preserved expression of the mismatch-repair proteins MLH1, PMS2, MSH2 and MSH6, indicating a microsatellite stable phenotype of carcinoma.

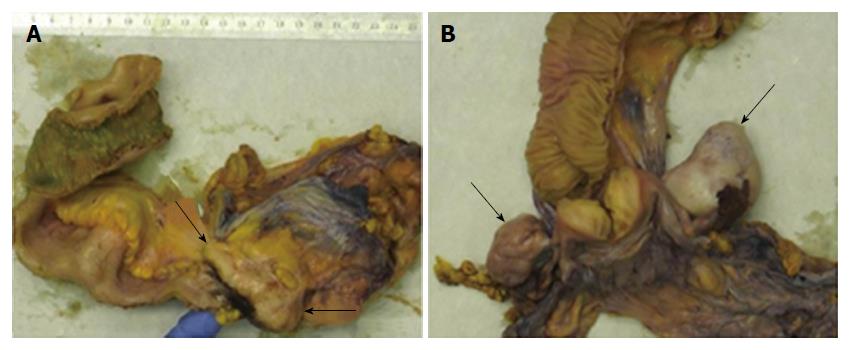

The pre-operative patient work-up included computed tomographic imaging of the chest and upper abdominal region, which revealed no extraintestinal manifestations of amebiasis, and explorative laparoscopy (Figure 4A and B) along with cytological examination of and biopsies from the peritoneum, which showed peritoneal carcinomatosis. After treatment with metronidazole, the patient underwent chemotherapy. Four months after diagnosis, right-sided hemicolectomy, omentectomy and Douglas-resection with hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were performed. Gross pathology of the surgical specimens showed tumor involvement of the cecum, the appendix and the ileocecal valve (Figure 5A). Metastases were found in the regional lymph nodes, the ovaries (Figure 5B), the fallopian tubes, the peritoneum, the omentum and the diaphragm. The biopsy-based diagnosis of signet-ring cell adenocarcinoma was confirmed by histology of the resected specimens (Figure 6A-F).

E. histolytica is a major cause of diarrhea in developing countries, primarily in tropical and subtropical regions with poor sanitation and inadequate barriers between food/water and human feces. In developed countries, most infections arise in immigrants and travelers from endemic areas. Young infants, pregnant women, malnourished individuals, and immunocompromised individuals are at highest risk for severe disease, which is characterized by complications such as perforation, toxic megacolon, fistulae, liver abscess and hemorrhage. Each year E. histolytica causes 40-50 million symptomatic infections worldwide, and approximately 40000 to 100000 people die each year from the disease, making this condition the second leading cause of death among parasitic diseases worldwide (after malaria)[9-11]. The majority of the patients (90%) remain asymptomatic[12,13]. Symptomatic patients can have simple acute proctocolitis or develop uncommon forms of GI involvement that include toxic megacolon, which is usually associated with corticosteroid treatment, abscess formation, and acute fulminant colitis with a mortality rate over 40%[14]. Clinical symptoms range from mild, with diarrhea, abdominal cramps and right lower quadrant tenderness (“non-dysenteric” infection), to severe, with abdominal cramps, fever and mucoid or bloody diarrhea (“dysenteric or invasive” infection).

The infestation begins with ingestion of E. histolytica cysts from food or water contaminated with feces. After digestion of the cysts in the intestinal lumen trophozoites are released. The trophozoites reproduce by clonal expansion and finally form cysts in the colon that are excreted in the feces and into the environment completing the life cycle of the parasite. E. histolytica has phagocytic, proteolytic and cytolytic capabilities and is known to secrete metabolic enzymes that facilitate their invasion into the mucosa and submucosa causing characteristic flask-shaped intestinal ulcers. The parasites may penetrate through the mucosa and submucosa into the portal circulation and reach internal organs such as the liver, lungs, skin, etc. Amebiasis may involve any part of the bowel, but the cecum and the ascending colon are predilection sites[9]. The most common extraintestinal manifestation is liver abscess caused by hematogenous spread from the GI tract.

The pathophysiological mechanism includes adhesion of E. histolytica to the intestinal epithelial cells via the Gal/GalNAc lectin (galactose/N-acetylgalactosamine specific lectin) triggering host cell death through phagocytosis, cytotoxicity and caspase activation. Other molecules involved in the disease process are amebapores, a serine-rich E. histolytica protein, and cysteine proteases[15,16]. The ulcers observed on endoscopy vary in size from pin-head size to large (> 2.5 cm in diameter), coalescing, geographic or serpiginous lesions with intervening normal mucosa. Amebomas, a late complication of the disease, are pseudo-tumoral lesions formed by granulation tissue with peripheral fibrosis and a core of chronic inflammation usually found in the cecum or ascending colon. Amebomas may cause obstructive symptoms and can be confused with malignancy. In addition, both the endoscopic appearance and the histologic features (including crypt architectural distortion, mural fibrosis and scarring) of chronic amebic colitis may resemble Crohn’s disease. In contrast to amebic colitis, Crohn’s disease does not spare the upper gastrointestinal tract and shows additional histological features typical of chronic idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease, such as granulomas, crypt abscesses and transmural lymphoid aggregates in the absence of protozoa.

Although a number of antigenic and molecular diagnostic tools have been developed over the years[17], the most commonly used method for diagnosis of intestinal amebiasis remains the examination of stool or intestinal biopsy by microscopy. The reported sensitivity of microscopic stool examination in identifying amebic protozoa ranges from 25% to 60%[18]. Histological features of E. histolytica include distinct cell membranes, foamy cytoplasm, round and eccentrically located nuclei with margination of nuclear chromatin, and ingested red blood cells. The parasites may resemble macrophages but are CD-68 negative, PAS and trichrome positive and have smaller nuclei. Because of the conversion of glucose and pyruvate to ethanol, these organisms are highly motile, resulting in a pleomorphic shape (with diameters ranging from 10 to 50 μm). In the current case, the diagnosis of colonic amebiasis and signet-ring cell carcinoma was established by histological examination of intestinal biopsy specimens showing the pathognomonic features of protozoa with ingested erythrocytes in combination with infiltrating tumor cells. While the findings were consistent with E. histolytica amebomas, antigenic or molecular tests for definitive species identification were not performed, posing a limitation to the current study. Thus, (co-)infection with other morphologically indistinguishable E. species (E. dispar and E. moshkovskii) cannot definitively be excluded. Several investigations provide evidence that the prevalence of E. histolytica, derived from studies using conventional diagnostic tools (microscopy and/or culture), is often overestimated because of its epidemiological overlap with non-pathogenic E. species, and only a proportion of microscopically positive stool samples are true E. histolytica infections as confirmed by polymerase chain reaction assay[19-22]. However, given that E. dispar is generally considered non-invasive and thus related to asymptomatic infections (despite emerging evidence that E. dispar can acquire pathogenicity in the presence of bacteria and produce significant lesions in the human intestine and liver[23]), based on the clinical presentation, E. histolytica is likely the causative agent of dysenteric colitis and amebomas in the current case.

Colonic amebiasis can mimic colon carcinoma clinically, radiologically and endoscopically[1-8]. Conversely, amebiasis and coexisting carcinoma are exceedingly rare[24-29]. In two African studies, colorectal carcinoma was found to be associated with intestinal amebiasis in 6.1% and 6.5% of cases[24,25]. Furthermore, five cases of cervical, perineal, sigmoid and pulmonary carcinomas colonized by E. histolytica have been described in three case reports[26-28]. However, apart from a single case study dated from 1963[29], to our knowledge the unique coincidence of colon carcinoma and amebomas has not been published previously in the literature.

The unusual co-occurrence of amebic infection and carcinoma poses particular challenges for both the pathologist and the clinician. Because coexisting malignancy in the setting of amebic disease can easily be overlooked, careful evaluation of individuals with amebiasis is necessary to confirm or rule out accompanying malignant disease.

A 35-year-old woman with no significant medical history, but a travel history to Nepal, presented with diarrhea and right-lower-quadrant abdominal pain and cramps of two months’ duration.

Right-lower-quadrant tenderness and mucoid diarrhea.

Carcinoma, lymphoma, tuberculosis or Crohn’s disease.

Laboratory tests showed neutrophilic leukocytosis and normocytic anemia, thought to be related to vitamin B-12 deficiency and occult intestinal bleeding.

Magnetic resonance imaging showed mural thickening of the cecum, appendix and adjacent terminal ileum. Colonoscopy disclosed multiple ulcerated, tumor-like masses (up to 33 mm in diameter) in the ascending colon and a 4.5 cm solid lesion at the ileocecal valve. Computed tomographic imaging of the chest and upper abdominal region revealed no extraintestinal mass-like lesions.

Amebomas and coexisting signet-ring cell carcinoma of the ileocecal valve, the cecum and the appendix with metastatic spread to the regional lymph nodes, ovaries, fallopian tubes, peritoneum, omentum and diaphragm.

Treatment with metronidazole followed by chemotherapy and right-sided hemicolectomy, omentectomy, hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

Several case reports emphasize that colonic amebiasis can mimic colon carcinoma leading to misdiagnosis. Rarely, colorectal carcinoma may be colonized by E. dispar and E. moshkovskii. Apart from a single case report, the unique coincidence of colon carcinoma and amebomas has not been published previously in the literature.

Amebomas, a late manifestation of amebiasis, are pseudo-tumoral lesions. They consist of granulation tissue with a core of chronic inflammation and typically occur in the cecum or ascending colon.

Colonic amebiasis can be confused with a neoplastic process. However, rarely, colon carcinoma and amebic disease may coexist in the same patient. Gastroenterologists and pathologists should be aware of this possibility and carefully evaluate patients with amebiasis to rule out concurrent malignancy.

The paper is well written. A limitation of the current study lies in the fact that definitive species identification was not performed using antigenic or molecular methods. However, the clinical presentation of the patient indicates that Entamoeba histolytica is likely the causative agent of dysenteric colitis and amebomas in the current case.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Switzerland

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Magana M, Osawa S, Williams BL S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Moorchung N, Singh V, Srinivas V, Jaiswal SS, Singh G. Caecal amebic colitis mimicking obstructing right sided colonic carcinoma with liver metastases: a rare case. J Cancer Res Ther. 2014;10:440-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lin CC, Kao KY. Ameboma: a colon carcinoma-like lesion in a colonoscopy finding. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2013;7:438-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ayari H, Rebii S, Ghariani W, Daghfous A, Hasni R, Rehaiem R, Rezgui-Marhoul L, Zoghlami A. [Colonic amoebiasis simulating a cecal tumor: case report]. Med Sante Trop. 2013;23:274-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Fernandes H, D’Souza CR, Swethadri GK, Naik CN. Ameboma of the colon with amebic liver abscess mimicking metastatic colon cancer. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:228-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Hardin RE, Ferzli GS, Zenilman ME, Gadangi PK, Bowne WB. Invasive amebiasis and ameboma formation presenting as a rectal mass: An uncommon case of malignant masquerade at a western medical center. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5659-5661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ng DC, Kwok SY, Cheng Y, Chung CC, Li MK. Colonic amoebic abscess mimicking carcinoma of the colon. Hong Kong Med J. 2006;12:71-73. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Simşek H, Elsürer R, Sökmensüer C, Balaban HY, Tatar G. Ameboma mimicking carcinoma of the cecum: case report. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:453-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ooi BS, Seow-Choen F. Endoscopic view of rectal amebiasis mimicking a carcinoma. Tech Coloproctol. 2003;7:51-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Stanley SL. Amoebiasis. Lancet. 2003;361:1025-1034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 915] [Cited by in RCA: 813] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Walsh JA. Problems in recognition and diagnosis of amebiasis: estimation of the global magnitude of morbidity and mortality. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8:228-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 442] [Cited by in RCA: 407] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Walsh J. Prevalence of Entamoeba histolytica infection. In: Ravdin JI. Amoebiasis: human infection by Entamoeba histolytica. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1988: 93-105. . |

| 12. | Gathiram V, Jackson TF. A longitudinal study of asymptomatic carriers of pathogenic zymodemes of Entamoeba histolytica. S Afr Med J. 1987;72:669-672. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Jackson TF, Gathiram V, Simjee AE. Seroepidemiological study of antibody responses to the zymodemes of Entamoeba histolytica. Lancet. 1985;1:716-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Necrotizing amebic colitis: a frequently fatal complication. Am J Surg. 1987;154:451, 458, 462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mortimer L, Chadee K. The immunopathogenesis of Entamoeba histolytica. Exp Parasitol. 2010;126:366-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Boettner DR, Hutson C, Petri Jr WA. Galactose/N-acetylgalactoseamine lectin: the coordinator of host cell killing. J Biosci. 2002;27:553-557. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Flores MS, Carrillo P, Tamez E, Rangel R, Rodríguez EG, Maldonado MG, Isibasi A, Galán L. Diagnostic parameters of serological ELISA for invasive amoebiasis, using antigens preserved without enzymatic inhibitors. Exp Parasitol. 2016;161:48-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Haque R, Huston CD, Hughes M, Houpt E, Petri WA. Amebiasis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1565-1573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 640] [Cited by in RCA: 563] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Yimer M, Zenebe Y, Mulu W, Abera B, Saugar JM. Molecular prevalence of Entamoeba histolytica/dispar infection among patients attending four health centres in north-west Ethiopia. Trop Doct. 2016; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kebede A, Verweij JJ, Endeshaw T, Messele T, Tasew G, Petros B, Polderman AM. The use of real-time PCR to identify Entamoeba histolytica and E. dispar infections in prisoners and primary-school children in Ethiopia. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2004;98:43-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fotedar R, Stark D, Marriott D, Ellis J, Harkness J. Entamoeba moshkovskii infections in Sydney, Australia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27:133-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nath J, Ghosh SK, Singha B, Paul J. Molecular Epidemiology of Amoebiasis: A Cross-Sectional Study among North East Indian Population. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Oliveira FM, Neumann E, Gomes MA, Caliari MV. Entamoeba dispar: Could it be pathogenic. Trop Parasitol. 2015;5:9-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ojo OS, Odesanmi WO, Akinola OO. The surgical pathology of colorectal carcinomas in Nigerians. Trop Gastroenterol. 1992;13:64-69. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Kenda JF. Cancer of the large bowel in the African: a 15-year survey at Kinshasa University Hospital, Zaïre. Br J Surg. 1976;63:966-968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mhlanga BR, Lanoie LO, Norris HJ, Lack EE, Connor DH. Amebiasis complicating carcinomas: a diagnostic dilemma. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;46:759-764. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Arroyo G, Elgueta R. Squamous cell carcinoma associated with amoebic cervicitis. Report of a case. Acta Cytol. 1989;33:301-304. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Zhu H, Min X, Li S, Feng M, Zhang G, Yi X. Amebic lung abscess with coexisting lung adenocarcinoma: a unusual case of amebiasis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:8251-8254. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Cannavo L. Sigmoid carcinoma in a patient with chronic amoebiasis or pseudoneoplastic amoebic granuloma (amoeboma). Panminerva Med. 1963;5:159-162. [PubMed] |