Published online Sep 21, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i35.8060

Peer-review started: May 29, 2016

First decision: June 20, 2016

Revised: June 30, 2016

Accepted: August 5, 2016

Article in press: August 5, 2016

Published online: September 21, 2016

Processing time: 108 Days and 7.6 Hours

To elucidate longitudinal changes of an endoscopic Barrett esophagus (BE), especially of short segment endoscopic BE (SSBE).

This study comprised 779 patients who underwent two or more endoscopies between January 2009 and December 2015. The intervals between the first and the last endoscopy were at least 6 mo. The diagnosis of endoscopic BE was based on the criteria proposed by the Japan Esophageal Society and was classified as long segment (LSBE) and SSBE, the latter being further divided into partial and circumferential types. The potential background factors that were deemed to affect BE change included age, gender, antacid therapy use, gastroesophageal reflux disease-suggested symptoms, esophagitis, and hiatus hernia. Time trends of a new appearance and complete regression were investigated by Kaplan-Meier curves. The factors that may affect appearance and complete regression were investigated by χ2 and Student-t tests, and multivariable Cox regression analysis.

Incidences of SSBE and LSBE were respectively 21.7% and 0%, with a mean age of 68 years. Complete regression of SSBE was observed in 61.5% of initial SSBE patients, while 12.1% of initially disease free patients experienced an appearance of SSBE. Complete regressions and appearances of BE occurred constantly over time, accounting for 80% and 17% of 5-year cumulative rates. No LSBE development from SSBE was observed. A hiatus hernia was the only significant factor that facilitated BE development (P = 0.03) or hampered (P = 0.007) BE regression.

Both appearances and complete regressions of SSBE occurred over time. A hiatus hernia was the only significant factor affecting the BE story.

Core tip: The authors demonstrated that the appearance or complete regression of Barrett esophagus (BE) occurs constantly over time. Both phenomena are associated with a hiatus hernia but not gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)-suggested symptoms, suggesting that the appearance of BE occurs silently. These findings imply that a lack of GERD-suggested symptoms is not sufficient to exclude patients from screening an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for identifying BE. The endoscopists should bear in mind that, along with the silent BE story, they should not miss the chance for the detection of BE and subsequent esophageal adenocarcinoma at an early, presymptomatic stage.

- Citation: Shimoyama S, Ogawa T, Toma T. Trajectories of endoscopic Barrett esophagus: Chronological changes in a community-based cohort. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(35): 8060-8066

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i35/8060.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i35.8060

Barrett esophagus (BE), a disease in which a squamous epithelium at the distal esophagus is replaced by a specialized intestinal metaplastic epithelium, has received increasing public health concern because of its potential for lesions that develop into esophageal adenocarcinoma. It is one of the histological consequences of long lasting gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and is classified into two types according to its length. Long segment BE (LSBE) denotes the length of specialized intestinal metaplasia of 3 cm or greater, while short segment BE (SSBE) is less than 3 cm. In contrast to the Western criteria[1,2], the Japan Esophageal Society proposed the concept of endoscopically diagnosed BE by the detection of longitudinal vessels in the distal side of the squamocolumnar junction (SCJ) without any histological evidence[3,4]. No requirement of biopsy specimens for the diagnosis of BE has lead general practitioners to promote a deeper awareness of the disease among the general population. We have previously published proof of the substantial incidence (22.1%) of SSBE[5], a rate comparable to or even higher than those assumed with great variation reported from Western[6] and Asian[7] countries. Surprisingly, we have also found that two thirds of SSBE patients were asymptomatic[5].

Whether the longer length of BE correlates to higher malignant potential of esophageal adenocarcinoma is controversial. Several studies have elucidated that SSBE and LSBE carry equivalent risks of esophageal adenocarcinoma[8,9], while a longer Barrett length possesses a higher risk of dysplasia[10,11] or subsequent esophageal adenocarcinoma than a shorter one[11,12]. Accordingly, every 1cm increase in BE length resulted in a 28% increase in the risk of high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma[13]. These results, although inconsistent, give credence to the notion that SSBE should not be overlooked, and that the development of SSBE as well as its progression from SSBE to LSBE may at least increase risks of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Inversely, a regression of BE, if it occurs, may be expected to lessen cancer risks.

In this regard, it is highly important to investigate changes in BE length and to explore factors associated with its change. Although many studies focusing on comparisons between longer and shorter BE at a given point consistently proved that a longer BE length was associated with obesity[14], the Caucasian race[15], older age[16], a longer hiatus hernia[16-19], a longer duration of acid exposure and subsequent GERD symptoms[16,18], while proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use correlated with shorter BE[16,17], the specific factors that could affect the elongation or regression of BE in an individual patient are still debated. With regard to LSBE, several investigators found that a regression of LSBE was accomplished by PPI use[20,21], no hiatal hernia[22], or length of columnar epithelium and less severe GERD[23], while others did not[24-26]. In addition to such inconsistencies in LSBE, research investigating chronological changes for SSBE are scanty in the literature[16,27,28]. Motivated by the limited knowledge on this matter, we have conducted a community-based longitudinal prospective study and demonstrated that both the appearance and complete regression of SSBE could occur constantly over time as well as that a hiatus hernia contributes to both phenomena.

Between January 2009 and December 2015, 1883 patients underwent a referral or screening endoscopy. The various clinical indications of referral endoscopy have been listed previously[5]. In brief, indications of referral endoscopy included GERD suggested symptoms as listed later or other gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain or loss of appetite with or without a clinically important weight loss. Other indications unrelated to gastrointestinal symptoms included abnormalities of laboratory findings or positive fecal occult blood test. Patients were excluded from this study if they underwent: (1) therapeutic or urgent endoscopies; (2) previous gastric or esophageal surgery including antireflux surgery; or (3) only a single endoscopy during the study period. Patients with a total follow up period of less than 6 mo were also excluded. Patients undergoing previous endoscopic mucosal resection outside the areas of SCJ were permitted. Consequently, 779 patients were eligible for inclusion in this study, each required to have two or more endoscopies during the study period; the presence or absence of, as well as the degrees of BE, were recorded at each endoscopy. The last date of follow up was 31st December 2015.

The diagnostic procedures and definition of BE have described previously[5]. In brief, we have noticed three important landmarks during endoscopic procedures with only minimal air inflation: a SCJ, diaphragmatic hiatus, and esophagogastric junction oriented by longitudinal vessels - if present, before the fiberscope was inserted into the stomach to avoid any push and pull effect of the endoscope. SCJ was defined as the distinct color difference between a whitish-gray smooth epithelium and reddish-orange velvety gastric mucosa. The diaphragmatic hiatus was defined at the point where the tubular esophagus flared to become the sac-like stomach. The distal limit of the longitudinal vessels emanating from the SCJ was defined as the esophagogastric junction[29,30]. Therefore, the area of longitudinal vessels located distal to the SCJ can be considered BE without any requirement of histological evidence[3,4], according to the Japan Esophageal Society (JES). Therefore, the area between the diaphragmatic hiatus and distal end of the longitudinal vessels, or between the diaphragmatic hiatus and SCJ in the case where no longitudinal vessels are observed, is recognized as a hiatus hernia. The BE was divided into two types according to its length: long segment BE (LSBE), when circumferentially recognized with a minimal length of 3 cm or more, or short segment BE (SSBE), for length of less than 3 cm. SSBE was further categorized as circumferential (cSSBE) and partial (pSSBE) types.

The chronological changes for BE during the follow up period were categorized into 6 groups using the following nomenclature: (1) disease free, no BE recognized; (2) persistence, pSSBE or cSSBE at the first endoscopy and no change thereafter; (3) appearance, no SSBE at the first endoscopy with a subsequent appearance of pSSBE or cSSBE at a follow-up endoscopy; (4) progression, progression from pSSBE to cSSBE; (5) complete regression, disappearance of pSSBE or cSSBE; and (6) partial regression, a regression from cSSBE to pSSBE. The background factors that potentially affect BE change included age, gender, antacid therapy use, GERD-suggested symptoms, esophagitis, and a hiatus hernia. GERD-suggested symptoms included heartburn, regurgitation, dysphagia, odynophagia, epigastralgia, belching, nausea and vomiting, and non-cardiac chest pain, as proposed in the published questionnaires. Esophagitis was diagnosed according to the Los Angeles Classification[31], and a grade A or higher was considered evidence of its presence. Use of a histamine-2 receptor antagonist or PPI was considered antacid therapy. These factors, except age, were dichotomized by categorizing either a presence or absence.

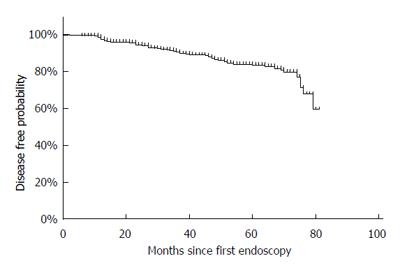

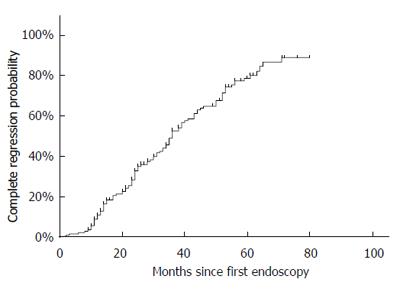

The relationship between these factors and changes in BE were investigated by univariate and multivariable[32] analyses. Fisher’s exact test and Student’s t test were respectively used for comparison of categorical and two mean values. Kaplan-Meier curves were used for the chronological changes for BE, especially for appearance and complete regression. For patients classified as disease-free at the first endoscopy, disease-free probability was calculated by using a time-length between the date of the first endoscopy and the date when the first appearance of pSSBE or cSSBE was noticed. For patients with SSBE at their first endoscopy, complete regression probability was calculated by using a time-length between the date of the first endoscopy and the date when the complete regression of pSSBE or cSSBE was first noticed.

The 779 patients were followed prospectively by a total of 2712 endoscopies for an average of 40.7 ± 21.3 mo (range, 6-81 mo) comprising a total of 31720 patient-months. Patient baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Overall, 292 (37.5%) patients took PPI or histamine-2 receptor antagonists.

| Mean age, yr (mean ± SD, range) | 68.1 ± 10.8 (27-95) |

| Gender (male/female) | 326/453 (41.8/58.2) |

| Antiacid therapy (present/absent) | 292/487 (37.5/62.5) |

| GERD-suggested symptoms (present/absent) | 414/365 (53.1/46.9) |

| Esophagitis (present/absent) | 81/698 (10.4/89.6) |

| Hiatus hernia (present/absent) | 704/75 (90.4/9.6) |

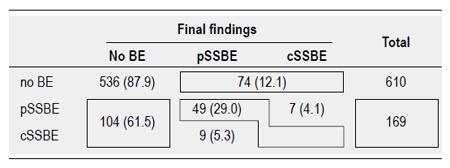

The patient distributions of the 6 categories of BE change are given in Figure 1. The incidence of SSBE at the first endoscopy was 21.7% (169 patients). Among these, complete regression and progression from pSSBE to cSSBE was respectively observed in 104 (61.5%) and 7 (4.1%) patients at their first endoscopy, while 49 (29.0%) SSBE remained stable during the study period. Among the 610 disease-free patients at the first endoscopy, SSBE developed in 74 patients, accounting for 12.1% of the appearance rate. None of the SSBE progressed to LSBE.

Kaplan-Meier analyses revealed that the appearance and complete regression occurred constantly over time (Figures 2 and 3). Five-year cumulative disease-free and complete regression probabilities were 83% and 80%. This meant that 5-year and annual appearance probabilities of SSBE were respectively 17% and 3.4%. The median persistent period of SSBE who experienced complete regression was 36 mo.

Multivariable Cox regression analysis revealed that a hiatus hernia was the only significant factor which both facilitates BE appearance and hampers BE regression (Table 2). Esophagitis appeared to be a marginally significant factor that hampers BE regression.

| Appearance | Complete regression | ||||

| Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Age | 0.98 (0.96-1.00) | 0.11 | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | 0.750 | |

| Gender | Male | 1 | 1 | ||

| Female | 1.01 (0.63-1.62) | 0.98 | 1.32 (0.88-1.97) | 0.180 | |

| Antiacid therapy | Absent | 1 | 1 | ||

| Present | 1.19 (0.74-1.93) | 0.47 | 0.73 (0.48-1.14) | 0.170 | |

| GERD-suggested symptoms | Absent | 1 | 1 | ||

| Present | 0.77 (0.46-1.19) | 0.22 | 0.98 (0.64-1.50) | 0.920 | |

| Esophagitis | Absent | 1 | 1 | ||

| Present | 1.09 (0.55-2.15) | 0.80 | 0.51 (0.26-1.01) | 0.052 | |

| Hiatus hernia | Absent | 1 | 1 | ||

| Present | 8.66 (1.20-62.6) | 0.03 | 0.13 (0.03-0.58) | 0.007 | |

The strength of our study is the simultaneous, multivariate, and longitudinal analyses investigating time trends of appearances or regressions of SSBE. Our main findings are that both the appearance and complete regression of SSBE occurred steadily over time, and that a hiatus hernia was the strongest and the only significant factor related to both phenomena.

In the West, the diagnosis of BE requires multiple, systematic targeted biopsies confirming specialized intestinal metaplasia[1] or columnar lined epithelium[2], as well as an endoscopic diagnosis of BE following Prague C and M criteria[33]. The proximal margin of the gastric fold is considered the gastroesophageal junction. On the other hand, it is widely accepted in Japan that longitudinal vessels emanating from, and located distally to the SCJ, can be considered BE, and no histological evidence of a goblet cell is mandatory[3,4]. We have previously discussed the merits of the Japanese criteria with regard to easy adoption of these criteria which enables endoscopists to facilitate BE description even for patients with conditions liable to bleeding[5]. Especially, the upper limit of the gastric folds is not located at a fixed position because it moves upward and downward according to breathing and the distending volume of air in the esophagus[34]. Noteworthily, the Western experts also recognized the distal margin of the palisade vessels and value of the Japanese criteria[35,36].

We have found in this study that a new appearance of SSBE occurred constantly over time, the 5-year cumulative appearance rate being approximately 17%. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report elucidating longitudinal time-trend profiles of new appearances of BE. Furthermore, a progression from pSSBE to cSSBE was seen in only a small fraction of patients (4.1%), findings which are indirectly supported by the observation of the occurrence of BE in a fairly rapid fashion, quickly reaching its maximal length with little increase thereafter[37].

In the present study, the complete regression rate was 61.5% at a mean follow-up length of 41 mo, and the 5-year cumulative complete regression rate was 80%. Controversies appear to exist in the literature concerning the rates and time-trend of BE regression. The complete regression rate in the present study is higher than those in the literature, ranging from 7%-44%[16,22,27,28]. In addition, antireflux surgery achieved steady SSBE regression[38], while a lack of further regression even after PPI therapy was noted[20]. However, direct comparisons of regression rates between previous studies and ours must be viewed with caution. In the previous studies, most patients were LSBE or the initial length of BE was at least 5 mm[16,22,27], while only SSBE patients even with partial types, regardless of length, were included in the present study. Although different criteria of SSBE at study entry undoubtedly make investigations difficult to compare, our results suggest that the cohort including pSSBE exhibits a substantial rate of regression. Indeed, the probability of BE regression may be length dependent[23,27] - a longer length of BE is less likely to regress completely.

Our multivariable analysis revealed that presence of a hiatus hernia was the only significant factor that both facilitates BE appearance and hampers BE regression. In addition, esophagitis was a marginally significant factor that hampers BE regression. These findings were supported by previous findings of extremely higher rates of a hiatus hernia among BE patients[19]. In addition, management of reflux resulted in a higher likelihood of BE regression, since antacid medication[20,21], antireflux surgery[38,39], and the presence or absence of hiatal hernia[22] were noted to be significant factors associated with BE regression. Given the role of antacid therapies on BE regression, it is conceivable that reduced lower esophageal sphincter pressure and subsequently developed hiatus hernia may promote BE. These considerations imply the importance of acid in the pathogenesis of BE.

Hiatus hernia is placed at the upstream condition that plays a causal role on lower esophageal disorders such as GERD, esophagitis, and eventual prescription of antacid medication. This provides one explanation why other background factors than hiatus hernia were not selected as significant factors associated with BE change. In this regard, the mode of categorizing hiatus hernia may be important, and a mere dichotomized category of hiatus hernia in the present study is a potential limitation. However, as discussed earlier, the length of hiatus hernia may not be fixed and therefore, the presence of hiatus hernia - a proof of reduced lower esophageal sphincter pressure - is applied in the present study rather than its length. Another potential limitation in this study is that body mass index or degree of obese - another potential factor that associated with hiatus hernia - was not included as a background factor. However, it should be noted that an association between obesity and BE has been controversial[40,41].

Surprisingly, our multivariable analysis elucidated that GERD-related symptoms were not a significant factor in the appearance or regression of BE. Although reflux symptoms correlated with longer BE, GERD alone is not sufficient to recommend screening an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for identifying BE[42]. We have previously demonstrated that two-thirds of SSBE patients had silent symptoms, suggesting that asymptomatic patients do carry SSBE and their appearance cannot be predicted by symptoms. These previous findings from ours[5] and others[42-45] could raise awareness that changes in findings around the region of SCJ, either appearance or complete regression, could occur regardless of GERD-related symptoms. This could further imply that excluding patients from screening based on a lack of GERD-related symptoms could surpress chances of detection of esophageal adenocarcinoma at an early, presymptomatic stage.

In the present study, only 7 patients (4.1%) experienced progression from pSSBE to cSSBE. The small number of patients experiencing the progression of SSBE in the present study precludes drawing a firm conclusion with regard to factors affecting BE progression. The progression rate of 4.1% in the present study was comparable to a previous study[46], in which the majority of SSBE patients remained stable and its elongation was observed in only 6% of patients.

Our clinic is one of the institutions which cover over 130000 residents. Under these circumstances, our study was conducted at a single community unit with patients undergoing an endoscopy regardless of GERD symptoms. Our clinic is a primary institution where the mean number of endoscopies performed is approximately 600 per year. Our study holds up as a representative population sample, being aged 27 to 95 years of residents easily accessible to our clinic, and thus may differ from all the potentially biased cohorts reported earlier. This could further support the idea that the regression rate could be extrapolated to the general Japanese population. Although our study did not include Caucasian patients, endoscopists should continuously be aware of a BE story - both the regression and appearance of SSBE steadily occurring - under the circumstances of a substantial incidence of hiatus hernias and with the knowledge that substantial numbers of BE patients are asymptomatic[5,37,42].

In conclusion, both appearances and complete regressions of SSBE occurred over time. A hiatus hernia was the only significant factor affecting the BE story, while substantial numbers of BE patients are asymptomatic.

Despite a growing awareness of Barrett esophagus (BE) in the context of the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma, knowledge on time-trends of appearances and changes of BE, especially short segment endoscopic BE (SSBE), is scarce in the literature.

Against the background of BE as a susceptible lesion of esophageal adenocarcinoma, it is important to elucidate longitudinal changes for BE and factors associated with it. With easy adoption by general practitioners, the authors applied endoscopic diagnoses of BE by detecting longitudinal vessels proposed by the Japanese criteria. No requirement of histological findings enables the facilitation of an endoscopic diagnosis of BE among the general population and for general practitioners.

The appearance or complete regression of BE occurs constantly over time. Both phenomena are associated with a hiatus hernia but not gastroesophageal reflux disease-suggested symptoms, suggesting that the appearance of BE occurs silently among a non-biased study population that resembles that seen by the general practitioner.

Despite the incidence of a hiatus hernia being dependent on its diagnostic criteria, a higher incidence of hiatus hernias and the existence of silent SSBE motivates endoscopists to assess the distal esophagus in all patients undergoing an upper endoscopy for any indication. This stance allows the detection of SSBE at an early stage to enable patients to enter a follow-up program as well as the early detection of eventual esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Endoscopic BE is defined according to the Japan Esophageal Society. The existence of longitudinal vessels emanating from the squamocolumnar junction is defined as endoscopic BE. BE is classified into two categories according to its length, long segment BE being 3 cm or more, and short segment BE being less than 3 cm. The length is further classified as partial and circumferential types. Changes in BE was classified as disease free, or showing persistence, appearance, progression, complete regression, and partial regression.

Although this study is based on the endoscopic diagnosis of BE, the authors’ unbiased population could be considered more suitable than surrogate unrepresentative clinical samples for quantifying the magnitude of the BE story. This study contributes important evidence and reliable connections between the BE story and a silent hiatus hernia, and thus provides guidance for not overlooking the chance for the detection of BE as well as subsequent esophageal adenocarcinoma at an early, presymptomatic stage.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Nathanson BH, Sanaei O S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Wang KK, Sampliner RE. Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:788-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 850] [Cited by in RCA: 786] [Article Influence: 46.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Playford RJ. New British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2006;55:442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hoshihara Y, Kogure T. What are longitudinal vessels? Endoscopic observation and clinical significance of longitudinal vessels in the lower esophagus. Esophagus. 2006;3:145-150. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Takubo K, Arai T, Sawabe M, Miyashita M, Sasajima K, Iwakiri K, Mafune K. Structures of the normal esophagus and Barett’s esophagus. Esophagus. 2003;1:37-47. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shimoyama S, Ogawa T, Toma T, Hirano K, Noji S. A substantial incidence of silent short segment endoscopically suspected esophageal metaplasia in an adult Japanese primary care practice. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:38-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ward EM, Wolfsen HC, Achem SR, Loeb DS, Krishna M, Hemminger LL, DeVault KR. Barrett’s esophagus is common in older men and women undergoing screening colonoscopy regardless of reflux symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:12-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Amano Y, Kinoshita Y. Barrett esophagus: perspectives on its diagnosis and management in asian populations. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2008;4:45-53. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Thomas T, Abrams KR, De Caestecker JS, Robinson RJ. Meta analysis: Cancer risk in Barrett’s oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1465-1477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gatenby PA, Caygill CP, Ramus JR, Charlett A, Fitzgerald RC, Watson A. Short segment columnar-lined oesophagus: an underestimated cancer risk? A large cohort study of the relationship between Barrett’s columnar-lined oesophagus segment length and adenocarcinoma risk. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:969-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Gopal DV, Lieberman DA, Magaret N, Fennerty MB, Sampliner RE, Garewal HS, Falk GW, Faigel DO. Risk factors for dysplasia in patients with Barrett’s esophagus (BE): results from a multicenter consortium. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1537-1541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hirota WK, Loughney TM, Lazas DJ, Maydonovitch CL, Rholl V, Wong RK. Specialized intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: prevalence and clinical data. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:277-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 379] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Weston AP, Badr AS, Hassanein RS. Prospective multivariate analysis of clinical, endoscopic, and histological factors predictive of the development of Barrett’s multifocal high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3413-3419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Anaparthy R, Gaddam S, Kanakadandi V, Alsop BR, Gupta N, Higbee AD, Wani SB, Singh M, Rastogi A, Bansal A. Association between length of Barrett’s esophagus and risk of high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma in patients without dysplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1430-1436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shinkai H, Iijima K, Koike T, Abe Y, Dairaku N, Inomata Y, Kayaba S, Ishiyama F, Oikawa T, Ohyauchi M. Association between the body mass index and the risk of Barrett’s esophagus in Japan. Digestion. 2014;90:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wong A, Fitzgerald RC. Epidemiologic risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus and associated adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1-10. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Okita K, Amano Y, Takahashi Y, Mishima Y, Moriyama N, Ishimura N, Ishihara S, Kinoshita Y. Barrett’s esophagus in Japanese patients: its prevalence, form, and elongation. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:928-934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dickman R, Green C, Chey WD, Jones MP, Eisen GM, Ramirez F, Briseno M, Garewal HS, Fass R. Clinical predictors of Barrett’s esophagus length. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:675-681. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Wakelin DE, Al-Mutawa T, Wendel C, Green C, Garewal HS, Fass R. A predictive model for length of Barrett’s esophagus with hiatal hernia length and duration of esophageal acid exposure. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:350-355. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Cameron AJ. Barrett’s esophagus: prevalence and size of hiatal hernia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2054-2059. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Wilkinson SP, Biddlestone L, Gore S, Shepherd NA. Regression of columnar-lined (Barrett’s) oesophagus with omeprazole 40 mg daily: results of 5 years of continuous therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1205-1209. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Peters FT, Ganesh S, Kuipers EJ, Sluiter WJ, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Lamers CB, Kleibeuker JH. Endoscopic regression of Barrett’s oesophagus during omeprazole treatment; a randomised double blind study. Gut. 1999;45:489-494. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Weston AP, Badr AS, Hassanein RS. Prospective multivariate analysis of factors predictive of complete regression of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3420-3426. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Horwhat JD, Baroni D, Maydonovitch C, Osgard E, Ormseth E, Rueda-Pedraza E, Lee HJ, Hirota WK, Wong RK. Normalization of intestinal metaplasia in the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: incidence and clinical data. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:497-506. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Cooper BT, Chapman W, Neumann CS, Gearty JC. Continuous treatment of Barrett’s oesophagus patients with proton pump inhibitors up to 13 years: observations on regression and cancer incidence. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:727-733. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Kastelein F, Spaander MC, Steyerberg EW, Biermann K, Valkhoff VE, Kuipers EJ, Bruno MJ. Proton pump inhibitors reduce the risk of neoplastic progression in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:382-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hornung CA. Do proton pump inhibitors induce regression of barrett’s esophagus? A systematic review. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:A152. |

| 27. | Brown CS, Lapin B, Wang C, Goldstein JL, Linn JG, Denham W, Haggerty SP, Talamonti MS, Howington JA, Carbray J. Predicting regression of Barrett’s esophagus: results from a retrospective cohort of 1342 patients. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2803-2807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Gatenby PA, Ramus JR, Caygill CP, Watson A. Does the length of the columnar-lined esophagus change with time? Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:497-503. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Ogiya K, Kawano T, Ito E, Nakajima Y, Kawada K, Nishikage T, Nagai K. Lower esophageal palisade vessels and the definition of Barrett’s esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:645-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Takubo K, Honma N, Aryal G, Sawabe M, Arai T, Tanaka Y, Mafune K, Iwakiri K. Is there a set of histologic changes that are invariably reflux associated? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:159-163. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Armstrong D, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Dent J, De Dombal FT, Galmiche JP, Lundell L, Margulies M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ. The endoscopic assessment of esophagitis: a progress report on observer agreement. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:85-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 754] [Cited by in RCA: 779] [Article Influence: 26.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hidalgo B, Goodman M. Multivariate or multivariable regression? Am J Public Health. 2013;103:39-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Sharma P, Dent J, Armstrong D, Bergman JJ, Gossner L, Hoshihara Y, Jankowski JA, Junghard O, Lundell L, Tytgat GN. The development and validation of an endoscopic grading system for Barrett’s esophagus: the Prague C & M criteria. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1392-1399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 731] [Cited by in RCA: 716] [Article Influence: 37.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Takubo K, Vieth M, Aida J, Sawabe M, Kumagai Y, Hoshihara Y, Arai T. Differences in the definitions used for esophageal and gastric diseases in different countries: endoscopic definition of the esophagogastric junction, the precursor of Barrett’s adenocarcinoma, the definition of Barrett’s esophagus, and histologic criteria for mucosal adenocarcinoma or high-grade dysplasia. Digestion. 2009;80:248-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Armstrong D. Review article: towards consistency in the endoscopic diagnosis of Barrett’s oesophagus and columnar metaplasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20 Suppl 5:40-47; discussion 61-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kusano C, Kaltenbach T, Shimazu T, Soetikno R, Gotoda T. Can Western endoscopists identify the end of the lower esophageal palisade vessels as a landmark of esophagogastric junction? J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:842-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Cameron AJ, Lomboy CT. Barrett’s esophagus: age, prevalence, and extent of columnar epithelium. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1241-1245. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Sagar PM, Ackroyd R, Hosie KB, Patterson JE, Stoddard CJ, Kingsnorth AN. Regression and progression of Barrett’s oesophagus after antireflux surgery. Br J Surg. 1995;82:806-810. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Csendes A, Bragheto I, Burdiles P, Smok G, Henriquez A, Parada F. Regression of intestinal metaplasia to cardiac or fundic mucosa in patients with Barrett’s esophagus submitted to vagotomy, partial gastrectomy and duodenal diversion. A prospective study of 78 patients with more than 5 years of follow up. Surgery. 2006;139:46-53. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Akiyama T, Yoneda M, Maeda S, Nakajima A, Koyama S, Inamori M. Visceral obesity and the risk of Barrett’s esophagus. Digestion. 2011;83:142-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Thrift AP, Hilal J, El-Serag HB. Metabolic syndrome and the risk of Barrett’s oesophagus in white males. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:1182-1189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Winters C, Spurling TJ, Chobanian SJ, Curtis DJ, Esposito RL, Hacker JF, Johnson DA, Cruess DF, Cotelingam JD, Gurney MS. Barrett’s esophagus. A prevalent, occult complication of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:118-124. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Gerson LB, Shetler K, Triadafilopoulos G. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in asymptomatic individuals. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:461-467. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Rex DK, Cummings OW, Shaw M, Cumings MD, Wong RK, Vasudeva RS, Dunne D, Rahmani EY, Helper DJ. Screening for Barrett’s esophagus in colonoscopy patients with and without heartburn. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1670-1677. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Desilets DJ, Nathanson BH, Bavab F. Barrett’s esophagus in practice: Gender and screening issues. J Men’s Health. 2014;11:177-182. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Manabe N, Haruma K, Imamura H, Kamada T, Kusunoki H, Inoue K, Shiotani A, Hata J. Does short-segment columnar-lined esophagus elongate during a mean follow-up period of 5.7 years? Dig Endosc. 2011;23:166-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |