Published online Mar 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2739

Peer-review started: June 17, 2014

First decision: August 6, 2014

Revised: August 29, 2014

Accepted: December 5, 2014

Article in press: December 8, 2014

Published online: March 7, 2015

Processing time: 265 Days and 17.1 Hours

AIM: To investigate the dynamic changes of serum hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) levels apportioned by the same hepatic parenchyma cell volume (HPCV), namely, hepatic cell quantities.

METHODS: Serum HBsAg levels were detected by electrochemiluminescence and serum HBsAg levels apportioned by the same HPCV were figured out according to the theory of sphere geometry. HBsAg levels were compared among different liver inflammation grades, as well as different hepatic fibrosis stages.

RESULTS: In hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B, serum HBsAg levels in liver histological inflammation grades 1-4 were 3.66 ± 0.40, 3.74 ± 0.35, 3.74 ± 0.26 and 3.71 ± 0.34 log10 COI (cut off index), respectively, and there were no differences before apportion (P = 0.640). Serum HBsAg levels apportioned by the same HPCV were 5.57 ± 0.62, 5.98 ± 0.65, 6.59 ± 0.50 and 6.81 ± 0.84 log10 COI, respectively, and there were significant differences after apportion (P < 0.001). Serum HBsAg levels in hepatic fibrosis stages I-IV were 3.66 ± 0.43, 3.75 ± 0.33, 3.71 ± 0.28 and 3.75 ± 0.26 log10 COI, respectively, and there were no differences before apportion (P = 0.513). Serum HBsAg levels apportioned by the same HPCV were 5.53 ± 0.66, 5.98 ± 0.53, 6.29 ± 0.46 and 7.06 ± 0.48 log10 COI, respectively, and there were significant differences after apportion (P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION: Serum HBsAg levels apportioned by the same HPCV (hepatic cell quantities), rather than serum HBsAg levels, increase with liver inflammation grades and hepatic fibrosis stages.

Core tip: Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-negative chronic hepatitis B patients always feature increasing liver fibrosis and decreasing hepatic parenchyma cells. Does it influence the circulating HBsAg released into the serum? It requires research on the condition that the impact of fibrous volume on hepatic cell quantities should be deducted. It turns out that there were significant differences in serum HBsAg levels apportioned by the same hepatic cell quantities among different liver histological inflammation grades, as well as different hepatic fibrosis stages. In conclusion, although hepatitis B virus replication place - hepatic cell quantities - were shrinking while fibrosis progresses, its replication and expression became more active rather than declined or silenced.

- Citation: Wu ZQ, Tan L, Liu T, Gao ZL, Ke WM. Evaluation of changes of serum hepatitis B surface antigen from a different perspective. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(9): 2739-2745

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i9/2739.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2739

According to global advances in the chronic hepatitis B (CHB) research at present, testing for serum hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is still very important in diagnosis of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection[1]. HBsAg clearance is the desired end point of clinical treatment for CHB[2]. In the natural course of CHB, as many researches demonstrated, serum HBsAg titers usually rise up again in hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) negative hepatitis patients except the immune tolerance phase[3]. Thus, HBsAg monitoring can be used as a sign of HBV reactivation to determine the risk of disease activity[4,5]. In HBeAg-negative patients who have HBV DNA levels < 2000 IU/mL, HBsAg level < 10 IU/mL is the strongest predictor of HBsAg loss[6]. During the antiviral therapy, monitoring serum HBsAg levels dynamically may have high value for prediction of sustained virological response and HBsAg clearance[7-10]. Patients with HBeAg-negative CHB are older and have more advanced liver disease since these patients represent a later stage in the natural course of chronic HBV infection[11,12]. With the continually increasing liver fibrosis and decreasing hepatic parenchyma cells, less and less place - the amount of hepatic parenchyma cells - can be provided to HBV replication. Does it influence the circulating HBsAg released into the serum? Therefore, it is necessary to figure out the dynamic expression pattern of serum HBsAg levels, and the serum HBsAg levels apportioned by the same hepatic parenchyma cell volume (HPCV), namely hepatic cell quantities, in different liver histological inflammation grades (1-4) as well as different hepatic fibrosis stages (I-IV). This will help clarify the pathogenesis of HBeAg-negative CHB, monitor the progression of the disease and provide a theoretic basis for optimization of antiviral therapy.

One hundred and sixty patients with HBeAg-negative CHB recruited from January 2008 to October 2012 in the admission office, Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China, were studied. There were 131 males and 29 females with a median age of 38.7 years (range: 13-67 years). All patients received no antiviral therapy such as nucleosides, interferon or thymosin during the study. None of the individuals included had hepatitis C virus, hepatitis D virus, hepatitis E virus or human immunodeficiency virus co-infection. Further exclusion criteria were end-stage liver insufficiency, autoimmune disorders, immunosuppressive treatment and malignancies.

All the 160 HBeAg-negative CHB patients in our retrospective investigation had been informed of possible complications with liver biopsies clearly before the invasive operation, such as local tissue injury, bile duct injury, bleeding, postoperative pain, anesthesia accident and other unexpected possible situations. The liver biopsies, which were not done for the study, were part of standard diagnosis and treatment for these patients. All patients had gave informed consent for every diagnosis and treatment, including the liver biopsies to be performed. All patients’ data we used were fully anonymized. None of the authors of this study had any involvement with the patients or performed any liver biopsies. Because this is a retrospective study to collect existing data of our own department, we did not seek approval by any ethics committee.

Quantitative detection were performed with Elecsys (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim). The judgment standards are stated as follows: reference ranges of HBsAg, anti-HBs, HBeAg, anti-HBe and anti-HBc are < 1.0 (cut off index, COI), 0-10 IU/L, < 1.0 COI, > 1.0 COI and > 1.0 COI, respectively. The test results of COI values read positive within the reference ranges while negative without it.

Liver biopsies in 160 HBeAg-negative CHB patients were performed with an automatic gun mating 16G needle guided by an Esaote AU4 color Doppler system (Esaote, United States). The obtained section of each sample was about 20 mm in length. The biopsy specimens were fixed with Bouin’s solution, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin and Masson’s trichrome. Liver histological inflammation grades and hepatic fibrosis stages were diagnosed according to the Desmet VJ chronic hepatitis classification by liver pathologists at our hospital[13].

Using JVC-KY-F30B3-CCD lens (Japan) and Zeiss Axiotron microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc, Germany), the measurements of hepatic fibrosis proportion were performed with an automatic imaging analysis system (KONTRON IBAS 2.5, Germany). Five fields of each microscopic view were randomly selected at four corners and the center of hepatic tissue section for calculation of average fibrous percentages in different fibrosis stages. This means that totally 200, 245, 120 and 155 microscopic views were averaged to calculate the fibrous percentages in hepatic fibrosis stages I-IV, respectively[14]. The images were magnified 400 times by a microscope. The average fibrosis proportion percents in different fibrosis stages were exactly the average fibrous percentages of section at those four fibrosis stages.

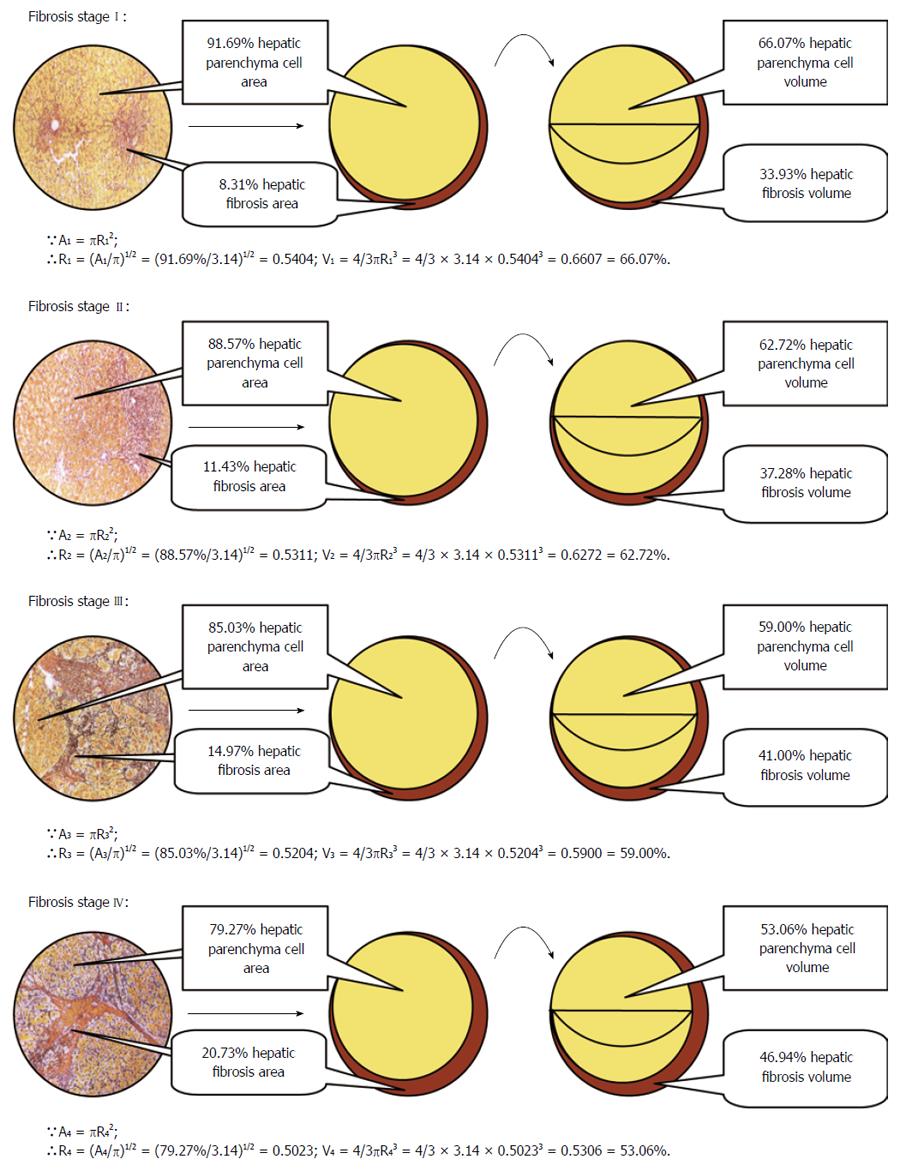

The liver consists of a majority of hepatic parenchyma cells, a minority of sinusoidal endothelial cells, Kupffer cells and mesenchymal cells. Therefore, the HPCV can almost represent the quantities of hepatocytes. According to the basic principles of microscope, the 100% circle area of microscopic view under the microscope in hepatic fibrosis stages I, II, III or IV was mainly made up of two parts: the proportion of hepatic parenchyma cell area and corresponding proportion of hepatic fibrosis area. Based on automatic imaging analysis in our previous research, the area proportions of hepatic fibrosis were 8.31% ± 2.90%, 11.43% ± 2.76%, 14.97% ± 5.88% and 20.73% ± 4.44% in hepatic fibrosis stages I-IV, respectively[14], while the corresponding proportions of hepatic parenchyma cell area were 91.69%, 88.57%, 85.03%, and 79.27%, respectively.

According to the principles of liver histopathological section and the circle view of microscope, each circular image of hepatic parenchyma cells and hepatic fibrous tissues under the microscope was classified into internal smaller circle hepatic parenchyma cell area and peripheric lunular fibrous tissues area. What means that the 100% circle area of microscopic view = 91.67%, 88.57%, 85.03% and 79.27% of internal smaller rotundity hepatic parenchyma cell area + 8.31%, 11.43%, 14.97% and 20.73% of peripheric lunular fibrous tissues area in hepatic fibrosis stages I-IV, respectively.

Because the rotundity area formula is A = πR2, the radius (R) of internal smaller circle hepatic parenchyma cell area is equal to root of the ratio of internal smaller circle hepatic parenchyma cell area (A) to pi (π), namely R = (A/π)2/1. The radii of the rotundity hepatic parenchyma cell area in hepatic fibrosis stages I-IV are (91.69%/3.14)2/1 = 0.5404, (88.57%/3.14)2/1 = 0.5311, (85.03%/3.14)2/1 = 0.5204 and (79.27%/3.14)2/1 = 0.5023, respectively. Further, as the formula of sphere volume (V) is V = 4/3πR3, the three-dimensional sphere HPCV values are V1 = 4/3πR13 = 4/3 × 3.14 × 0.54043 = 66.07%, V2 = 4/3πR23 = 4/3 × 3.14 × 0.53113 = 62.72%, V3 = 4/3πR33 = 4/3 × 3.14 × 0.52043 = 59.00% and V4 = 4/3πR43 = 4/3 × 3.14 × 0.50233 = 53.06% in hepatic fibrosis stages I-IV, respectively. Accordingly, the crescent hepatic fibrosis volumes in hepatic fibrosis stages I-IV are 100% - 66.07% = 33.93%, 100% - 62.72% = 37.28%, 100% - 59.00% = 41.00% and 100% - 53.06% = 46.94%, respectively. The reasoning and computational processes are shown in Figure 1.

By dividing the logarithms of HBsAg by the percentage of HPCV in each hepatic fibrosis stage that they located, we got the logarithm values of serum HBsAg apportioned by the same HPCV (hepatic cell quantities).

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 13.0 software. Serum HBsAg levels were logarithmically transformed for analysis. Correlation analysis between liver inflammation grades and hepatic fibrosis stages was done using χ2 test. The comparisons among more than two groups in serum HBsAg levels and HBsAg levels apportioned by the same HPCV in hepatic fibrosis stages I-IV were done using ANOVA test. P values < 0.008 (0.05/6) were considered significant.

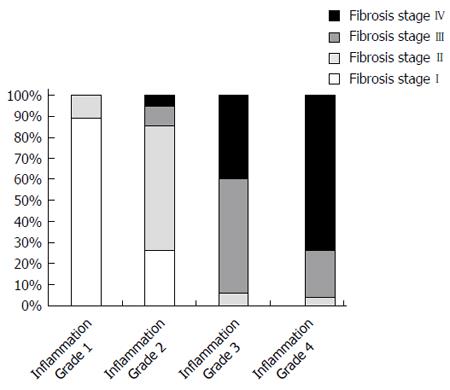

Overall, the distribution of liver inflammation grades was similar to that of the corresponding hepatic fibrosis stages in HBeAg-negative CHB patients in pathologic diagnosis (Figure 2). The milder the liver inflammation grades, the milder the hepatic fibrosis stages. Likewise, the severer the liver inflammation grades, the severer the hepatic fibrosis stages. Liver inflammation grades correlated well with hepatic fibrosis stages (χ2 = 187.635, P < 0.001).

In HBeAg-negative CHB, there was no obvious rule for dynamic changes of serum HBsAg levels no matter among different liver inflammation grades or hepatic fibrosis stages. However, serum HBsAg levels apportioned by the same HPCV (hepatic cell quantities) elevated with the increasing inflammation grades and fibrosis stages (Table 1). There was no differences in serum HBsAg levels no matter among different liver inflammation grades or hepatic fibrosis stages (F = 0.564, P = 0.640 and F = 0.768, P = 0.513, respectively; Table 2). However, there were significant differences in serum HBsAg levels apportioned by the same HPCV among inflammation grades 1-4 and fibrosis stages I-IV (F = 27.354, P < 0.000 and F = 57.077, P < 0.000, respectively; Table 2).

| Case, n | Serum HBsAg(log10 COI) | Serum HBsAg apportioned bythe same HPCV (log10 COI) | |

| G1 | 44 | 3.66 ± 0.40 | 5.57 ± 0.62 |

| G2 | 54 | 3.74 ± 0.35 | 5.98 ± 0.65 |

| G3 | 35 | 3.74 ± 0.26 | 6.59 ± 0.50 |

| G4 | 27 | 3.71 ± 0.34 | 6.81 ± 0.84 |

| S1 | 53 | 3.66 ± 0.43 | 5.53 ± 0.66 |

| S2 | 40 | 3.75 ± 0.33 | 5.98 ± 0.53 |

| S3 | 30 | 3.71 ± 0.28 | 6.29 ± 0.46 |

| S4 | 37 | 3.75 ± 0.26 | 7.06 ± 0.48 |

| Serum HBsAg | Serum HBsAg apportioned by HPCV | Serum HBsAg | Serum HBsAg apportioned by HPCV | ||

| G1 + G2 | 0.233 | 0.002 | S1 + S2 | 0.186 | 0.000 |

| G1 + G3 | 0.307 | 0.000 | S1 + S3 | 0.497 | 0.000 |

| G1 + G4 | 0.575 | 0.000 | S1 + S4 | 0.222 | 0.000 |

| G2 + G3 | 0.960 | 0.000 | S2 + S3 | 0.613 | 0.024 |

| G2 + G4 | 0.655 | 0.000 | S2 + S4 | 0.947 | 0.000 |

| G3 + G4 | 0.712 | 0.194 | S3 + S4 | 0.663 | 0.000 |

| G1 to G4 | F = 0.564 | F = 27.354 | S1 to S4 | F = 0.768 | F = 57.077 |

| P = 0.640 | P = 0.000 | P = 0.513 | P = 0.000 |

So far serum HBsAg is still the most main and classic marker in the diagnosis of active infection with HBV[1]. HBsAg clearance is the desired end point of clinical treatment for CHB[15]. Baseline serum HBsAg level is the most effective predictor of HBsAg clearance[16]. As some studies showed[17,18], there is a good correlation among intrahepatic cccDNA levels, HBV DNA and HBsAg levels released into peripheral blood. Serum HBsAg can not only reflect the activity of virus replication indirectly, but also evaluate the damage of hepatocytes in CHB[19,20]. Owing to the fact that a rapid on-treatment decline of serum HBsAg levels predicts the effects of anti-HBV therapy[21], such as HBeAg serological conversion and HBsAg clearance, the dynamic monitoring of HBsAg is absolutely an indispensible indicator during the process of individualized therapy and follow-up[22].

HBeAg-negative CHB patients are older and have more advanced liver disease since these patients represent a later stage in the natural course of chronic HBV infection[11,12]. With the continually increasing liver fibrosis and decreasing hepatic parenchyma cells, less and less place - HPCV (hepatic cell quantities) - can be provided to HBV replication. It influences the circulating HBsAg released into serum probably. Therefore, it is necessary to figure out the dynamic expression pattern of serum HBsAg levels, and the serum HBsAg levels apportioned by the same HPCV (hepatic cell quantities) on the condition that the impact of fibrous volume on HPCV (hepatic cell quantities) should be deducted in liver inflammation grades 1-4, as well as hepatic fibrosis stages I-IV, respectively.

The liver consists of a majority of hepatic parenchyma cells, a minority of sinusoidal endothelial cells, Kupffer cells and mesenchymal cells. Therefore, the HPCV can almost represent the quantities of hepatocytes. We obtained the area proportions of hepatic fibrosis I-IV based on automatic imaging analysis in our previous research. Furthermore, according to the principles of liver histopathological section and the rotundity view of microscope, each circular image of hepatic parenchyma cells and hepatic fibrous tissues under the microscope was classified into internal smaller rotundity hepatic parenchyma cell area and peripheric lunular fibrous tissues area. The percentages of HPCV in hepatic fibrosis stages I-IV were calculated exactly on the basis of conversion from rotundity area to three-dimensional sphere volume. The reasoning and computational processes are shown in Figure 1.

As this study indicated, in patients with HBeAg-negative CHB, there was no differences in serum HBsAg levels, but significant differences in serum HBsAg levels apportioned by the same HPCV among inflammation grades 1-4 and fibrosis stages I-IV (P < 0.000 for both, Table 2). A study by Ke et al[23] has shown that the serum HBV DNA levels apportioned by the same HPCV increased along with the advanced liver inflammation grades when deducting the impact of fibrous volume on HPCV (hepatic cell quantities) in different fibrosis stages in both HBeAg-positive and negative CHB. Their finding corresponds well with this study. This may suggest that escalation of HBV replication in hepatocytes promotes the expression of serum HBsAg, aggravates the T cell mediated specific immune injury to the liver and results in more serious inflammation activities.

This study also showed that liver inflammation grades correlated well with hepatic fibrosis stages in HBeAg-negative hepatitis B (P < 0.000, Figure 2). While the liver inflammation grade was G1 or G2, the hepatic fibrosis stage was almost the milder S1 or S2. While the liver inflammation grade was G3 or G4, the hepatic fibrosis stage was almost the severer S3 or S4 as well. Because serious liver inflammation grades are often accompanied by accumulated serious hepatic fibrosis, the serum HBsAg levels apportioned by the same HPCV increased as the severity of hepatic fibrosis stages developed though the HPCV (hepatic cell quantities) shrank from hepatic fibrosis stage I to IV.

In conclusion, serum HBsAg levels apportioned by the same HPCV (hepatic cell quantities), rather than serum HBsAg levels, increased with the advance of liver inflammation grades and hepatic fibrosis stages on the condition that the impact of fibrous volume on HBV replication place – HPCV - was deducted in HBeAg-negative hepatitis B. Although HBV replication place - HPCV - was shrinking while HBeAg-negative CHB progresses, its replication and expression became more active rather than declined or silenced. Understanding the dynamic changes of HBsAg apportioned by the same HPCV throughout the natural history of CHB represents a step forward in further investigation of HBV viral lifecycle and the influence of host immune response. Compared to HBV DNA, quantitative HBsAg assays are easy to perform and relatively inexpensive[24]. Monitoring the dynamic changes of serum HBsAg apportioned by the same HPCV may predict HBsAg clearance more accurately and effectively. Maybe we should consider the liver inflammation grades and hepatic fibrosis stages in patients with HBeAg-negative CHB which represents a later stage in the natural course of chronic HBV infection when comes to anti-HBV therapy. It seems that only applying effective and low-resistant antiviral drugs to HBeAg-negative CHB patients with advanced liver inflammation and fibrosis, regardless of serum HBsAg levels, can control liver inflammation activity and reverse the formation of liver fibrosis suitably.

Serum hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is the most main and classic marker in diagnosis of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. HBsAg clearance is the desired end point of clinical treatment for chronic hepatitis B (CHB). Baseline serum HBsAg level is the most effective predictor of HBsAg clearance. Serum HBsAg level is the hotspot in CHB research field recently.

The global advances in CHB research suggest that dynamic monitoring of HBsAg titers may have high value for prediction of HBV reactivation, sustained virological response and HBsAg clearance.

This study brings hepatic parenchyma cell volume (HPCV) - the HBsAg replication place - into account. We think it is necessary to figure out the dynamic expression pattern of serum HBsAg levels, and the serum HBsAg levels apportioned by the same HPCV (hepatic cell quantities) on the condition that the impact of fibrous volume on HPCV (hepatic cell quantities) should be deducted.

Monitoring the dynamic changes of serum HBsAg apportioned by the same HPCV may help predict HBsAg clearance and supply antiviral therapy more accurately and effectively.

HPCV, namely, hepatic cell quantities, provides the replication place to HBV in the liver. Changing of HPCV (hepatic cell quantities) in natural course of HBeAg-negative CHB may influence the serum HBsAg titers.

The article researched the dynamic changes of serum HBsAg from a new perspective. It took the HBV replication place - HPCV (hepatic cell quantities) which may affect the serum HBsAg level - into consideration. The research method which referenced mathematics is very innovative. The research suggested that hepatic cell quantities were shrinking while fibrosis progresses, but serum HBsAg expression became more active rather than declined or silenced.

P- Reviewer: Sazci A, Wang ZC S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Merrill RM, Hunter BD. Seroprevalence of markers for hepatitis B viral infection. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15:e78-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver. [EASL clinical practice guidelines. Management of chronic hepatitis B]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2009;33:539-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liang TJ. Hepatitis B: the virus and disease. Hepatology. 2009;49:S13-S21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 747] [Cited by in RCA: 636] [Article Influence: 39.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nguyen T, Thompson AJ, Bowden S, Croagh C, Bell S, Desmond PV, Levy M, Locarnini SA. Hepatitis B surface antigen levels during the natural history of chronic hepatitis B: a perspective on Asia. J Hepatol. 2010;52:508-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jaroszewicz J, Calle Serrano B, Wursthorn K, Deterding K, Schlue J, Raupach R, Flisiak R, Bock CT, Manns MP, Wedemeyer H. Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) levels in the natural history of hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infection: a European perspective. J Hepatol. 2010;52:514-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 313] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tseng TC, Liu CJ, Yang HC, Su TH, Wang CC, Chen CL, Kuo SF, Liu CH, Chen PJ, Chen DS. Determinants of spontaneous surface antigen loss in hepatitis B e antigen-negative patients with a low viral load. Hepatology. 2012;55:68-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wursthorn K, Jung M, Riva A, Goodman ZD, Lopez P, Bao W, Manns MP, Wedemeyer H, Naoumov NV. Kinetics of hepatitis B surface antigen decline during 3 years of telbivudine treatment in hepatitis B e antigen-positive patients. Hepatology. 2010;52:1611-1620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Brunetto MR, Moriconi F, Bonino F, Lau GK, Farci P, Yurdaydin C, Piratvisuth T, Luo K, Wang Y, Hadziyannis S. Hepatitis B virus surface antigen levels: a guide to sustained response to peginterferon alfa-2a in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2009;49:1141-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 358] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Moucari R, Mackiewicz V, Lada O, Ripault MP, Castelnau C, Martinot-Peignoux M, Dauvergne A, Asselah T, Boyer N, Bedossa P. Early serum HBsAg drop: a strong predictor of sustained virological response to pegylated interferon alfa-2a in HBeAg-negative patients. Hepatology. 2009;49:1151-1157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 361] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sonneveld MJ, Rijckborst V, Boucher CA, Hansen BE, Janssen HL. Prediction of sustained response to peginterferon alfa-2b for hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B using on-treatment hepatitis B surface antigen decline. Hepatology. 2010;52:1251-1257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hadziyannis SJ, Vassilopoulos D. Hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2001;34:617-624. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Brunetto MR, Oliveri F, Coco B, Leandro G, Colombatto P, Gorin JM, Bonino F. Outcome of anti-HBe positive chronic hepatitis B in alpha-interferon treated and untreated patients: a long term cohort study. J Hepatol. 2002;36:263-270. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Chen M, Sällberg M, Hughes J, Jones J, Guidotti LG, Chisari FV, Billaud JN, Milich DR. Immune tolerance split between hepatitis B virus precore and core proteins. J Virol. 2005;79:3016-3027. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Xie SB, Yao JL, Zheng SS, Yao CL, Zheng RQ. The levels of serum fibrosis marks and morphometric quantitative measurement of hepatic fibrosis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2002;1:202-206. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Liaw YF, Chu CM. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2009;373:582-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 929] [Cited by in RCA: 993] [Article Influence: 62.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Arai M, Togo S, Kanda T, Fujiwara K, Imazeki F, Yokosuka O. Quantification of hepatitis B surface antigen can help predict spontaneous hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:414-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Locarnini S, Bowden S. Hepatitis B surface antigen quantification: not what it seems on the surface. Hepatology. 2012;56:411-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chan HL, Wong VW, Tse AM, Tse CH, Chim AM, Chan HY, Wong GL, Sung JJ. Serum hepatitis B surface antigen quantitation can reflect hepatitis B virus in the liver and predict treatment response. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1462-1468. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Ben Slama N, Ahmed SN, Zoulim F. [HBsAg quantification: virological significance]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34 Suppl 2:S112-S118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Brunetto MR, Oliveri F, Colombatto P, Moriconi F, Ciccorossi P, Coco B, Romagnoli V, Cherubini B, Moscato G, Maina AM. Hepatitis B surface antigen serum levels help to distinguish active from inactive hepatitis B virus genotype D carriers. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:483-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Viganò M, Lampertico P. Clinical implications of HBsAg quantification in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:81-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Janssen HL, Sonneveld MJ, Brunetto MR. Quantification of serum hepatitis B surface antigen: is it useful for the management of chronic hepatitis B? Gut. 2012;61:641-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ke WM, Xie SB, Li XJ, Zhang SQ, Lai J, Ye YN, Gao ZL, Chen PJ. There were no differences in serum HBV DNA level between HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B with same liver histological necroinflammation grade but differences among grades 1, 2, 3 and 4 apportioned by the same hepatic parenchyma cell volume. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:637-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kim H, Oh EJ, Kang MS, Kim SH, Park YJ. Comparison of the Abbott Architect i2000 assay, the Roche Modular Analytics E170 assay, and an immunoradiometric assay for serum hepatitis B virus markers. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2007;37:256-259. [PubMed] |