Published online Feb 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i6.1880

Peer-review started: June 17, 2014

First decision: July 21, 2014

Revised: August 13, 2014

Accepted: September 18, 2014

Article in press: September 19, 2014

Published online: February 14, 2015

Processing time: 239 Days and 18.9 Hours

AIM: To determine the efficacy and safety of rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus without a meal in steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis (UC) patients.

METHODS: This was a prospective, multicenter, observational study. Between May 2010 and August 2012, 49 steroid-refractory UC patients (55 flare-ups) were consecutively enrolled. All patients were treated with oral tacrolimus without a meal at an initial dose of 0.1 mg/kg per day. The dose was adjusted to maintain trough whole-blood levels of 10-15 ng/mL for the first 2 wk. Induction of remission at 2 and 4 wk after tacrolimus treatment initiation was evaluated using Lichtiger’s clinical activity index (CAI).

RESULTS: The mean CAI was 12.6 ± 3.6 at onset. Within the first 7 d, 93.5% of patients maintained high trough levels (10-15 ng/mL). The CAI significantly decreased beginning 2 d after treatment initiation. At 2 wk, 73.1% of patients experienced clinical responses. After tacrolimus initiation, 31.4% and 75.6% of patients achieved clinical remission at 2 and 4 wk, respectively. Treatment was well tolerated.

CONCLUSION: Rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus shortened the time to achievement of appropriate trough levels and demonstrated a high remission rate 28 d after treatment initiation. Rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus appears to be a useful therapy for the treatment of refractory UC.

Core tip: A prospective, multicenter, observation study was conducted to determine the efficacy and safety of rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus without meal in patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Rapid induction therapy could achieve the appropriate trough level (10-15 ng/mL) within the first 7 d and revealed a high remission rate 28 d after the initiation of the treatment. Treatment was well tolerated. Rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus appears to be a useful therapy for the treatment of refractory ulcerative colitis.

- Citation: Kawakami K, Inoue T, Murano M, Narabayashi K, Nouda S, Ishida K, Abe Y, Nogami K, Hida N, Yamagami H, Watanabe K, Umegaki E, Nakamura S, Arakawa T, Higuchi K. Effects of oral tacrolimus as a rapid induction therapy in ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(6): 1880-1886

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i6/1880.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i6.1880

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) characterized by a chronic relapsing/intermittent clinical course. Aminosalicylates are typically used as first-line treatment for patients with UC, while steroids are usually considered to be second-line treatment and are used to induce remission when remission cannot be achieved with aminosalicylates[1]. Because steroids have a rapid onset of action and are highly effective, they are reserved for disease that fails to respond to primary therapy in patients with severe UC. However, these agents are associated with considerable systemic adverse effects[2]. Nevertheless, approximately 20% of patients with UC have chronically active disease that requires several courses of steroids[3]. As a result, many steroid-dependent/-resistant patients experience severe complications of steroid treatment before stable remission can be achieved[3,4].

Calcineurin inhibitors, such as cyclosporine A (CsA) and tacrolimus, inhibit the production of interleukin-2 (IL-2) and activation of T lymphocytes[5]. Since these agents have a rapid onset of action and are highly effective in patients with refractory UC, they are approved as an alternative treatment option for refractory UC under the national health insurance system in Japan[6]. Previous reports have demonstrated the dose-dependent efficacy and safety of oral tacrolimus for remission-induction therapy in refractory UC[7,8]. With respect to efficacy, the optimal target tacrolimus blood concentration appears to be 10-15 ng/mL[7,8]. However, since oral tacrolimus has a slower onset of action compared to intravenous CsA[6], we have occasionally had severe UC patients who did not demonstrate improvement prior to achieving the appropriate trough level with oral tacrolimus using standard dosing (initial dose of 0.025 mg/kg twice daily). Even when the starting dose of tacrolimus is set to 0.1 mg/kg per day, it still takes more than 7 d to achieve the target tacrolimus blood concentration, because food intake is known to reduce serum levels of tacrolimus due to its low absorption rate[6,7]. Therefore, rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus, starting at 0.1 mg/kg per day without meals, should be recommended as a salvage therapy for patients with steroid-dependent/resistant UC. Meanwhile, higher tacrolimus starting doses have been reported to be associated with nephrotoxicity and to have no apparent therapeutic advantage over lower doses, suggesting that lower doses should be used to avoid adverse events[8]. However, thus far, no prospective studies designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus have been conducted. Therefore, we have conducted such a prospective, multicenter study, and report herein the efficacy and safety of rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus in steroid-refractory UC patients.

This was a prospective, multicenter, observational study involving three Japanese academic centers: Hyogo College of Medicine, Osaka City Graduate School of Medicine, and Osaka Medical College. Patients admitted to hospitals for the treatment of steroid-resistant or steroid-dependent moderate/severe UC were eligible. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) > 16 years of age at admission and capable of providing written informed consent; (2) diagnosis established according to standardized criteria with prior clinical assessments, radiology, endoscopy, and histology[9]; (3) steroid-resistant or steroid-dependent UC; and (4) active colitis as assessed by a Mayo score of 8-12[10]. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) under 16 years of age or unable to give informed consent; (2) prior abdominal surgery; (3) pregnant, at risk of pregnancy, or breast feeding; and (4) presence of active extra-intestinal infection, liver or kidney failure, or suspicious for diabetes. All patients were hospitalized and had left-sided UC (except for ulcerative proctitis) or extensive UC. The extent of colonic involvement was determined by total colonoscopy.

Patients were classified as having steroid-resistant or steroid-dependent disease in accordance with the definitions previously published by Ogata et al[7] Steroid resistance was defined as a lack of response to oral or intravenous steroid therapy (daily prednisolone dose > 30 mg) over at least 2 wk, and steroid dependence was defined as recurrent flare-up on steroid reduction or withdrawal, or chronic active UC for > 6 mo or frequent recurrence (more than once a year, or three times or more every two years, regardless of intensive medical therapy)[7,11]. Patients were permitted to continue taking drugs containing 5-aminosalicylic acid during this study. Patients who were already taking steroids and/or immunosuppressant agents (azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine) were also permitted to continue receiving these medications. However, the dosages of these agents were not allowed to be increased once the patients entered into this study. In addition, cytapheresis was prohibited during the study period.

This study was reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of each academic center. All patients were informed of the potential risks and benefits of tacrolimus therapy and provided signed informed consent forms before undergoing any procedures.

All patients were hospitalized at the time of initiation of tacrolimus therapy and given oral tacrolimus without a meal at an initial dose of 0.1 mg/kg per day, given in twice-daily divided doses. Blood was collected to determine the tacrolimus whole-blood trough concentrations at 24 h and at 2, 3, 4, and 7 d and every 7 d thereafter after the initial dose. The dose was adapted to maintain trough whole-blood levels of 10-15 ng/mL for the first 2 wk. The doses were adjusted using the equations shown in Table 1. After a high trough concentration (10-15 ng/mL) was achieved, patients could resume receiving meals. Beginning at 2 wk after the initiation of tacrolimus therapy, tacrolimus whole-blood trough concentrations were gradually maintained at a lower level of 5-10 ng/mL.

| Trough concentration | < Day 4 | Trough concentration | Days 4-14 |

| > 40 ng/mL | 0 mg/d | > 40 ng/mL | 0 mg/d |

| 25-40 ng/mL | -33% | 30-40 ng/mL | -50% |

| 20-30 ng/mL | -25% | ||

| 10-25 ng/mL | 0% | 10-20 ng/mL | 0% |

| < 10 ng/mL | 33% | < 10 ng/mL | 25% |

The primary endpoint of this study was the proportion of patients with improvement, [defined as a clinical response or clinical remission, based on Lichtiger’s clinical activity index (Lichtiger score)]. The secondary endpoint was safety. Patients were hospitalized until their clinical conditions had stabilized and their tacrolimus levels were within the therapeutic range. Lichtiger scores were obtained at 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, 21, and 28 d after the initiation of tacrolimus treatment. Response was defined as a Lichtiger score < 10 and a decrease ≥ 3 (in the case of patients with a Lichtiger score less than 10 on admission, response was defined as a Lichtiger score decrease > 3), and clinical remission was defined as a Lichtiger score ≤ 4[12,13]. Response rate and remission rate were defined as the proportion (%) of patients achieving response or remission, respectively[14]. Trough whole-blood levels and biochemical values, including serum creatinine and fasting blood glucose levels, were also measured.

Continuous data ware statistically analyzed using Student’s t-test. The Wilcoxon test was used to analyze clinical scores (i.e., Lichtiger scores). Results are expressed as the mean ± SD. P-values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All calculations were made using the Statview system (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States).

This study was performed between May 2010 and August 2012. A total of 49 patients (55 flare-ups) with steroid-resistant or steroid-dependent UC in three Japanese academic centers were enrolled. Baseline patient characteristics are shown in Table 2. According to the Montreal classification[15], 44 patients (89.8%) were afflicted with extensive UC, and 5 patients (10.2%) were afflicted with left-sided UC. The mean clinical activity index (CAI) was 12.6 ± 3.6 at onset, and all enrolled patients had a Lichtiger score ≥ 6. Of 49 patients, 4 patients were enrolled into this study twice, and 1 patient was enrolled three times, due to relapse. Two patients had steroid-resistant disease at first admission and steroid-dependent disease at second admission. Therefore, of the 49 patients, 38 patients (42 attacks) had steroid resistance and 13 patients (13 attacks) had steroid dependence; 2/49 patients were included in both groups because they had two different types of flare-ups.

| Patients, n | 49 |

| Attacks, n | 55 |

| Sex, M/F | 25/24 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 43.8 ± 16.0 |

| Extent of disease (left sided UC/extensive UC), n | 5/44 |

| CAI (mean ± SD) | 12.6 ± 3.9 |

| Steroid resistant/dependent, n | 38 cases, 42 flare-ups/13 cases, 13 flare-ups |

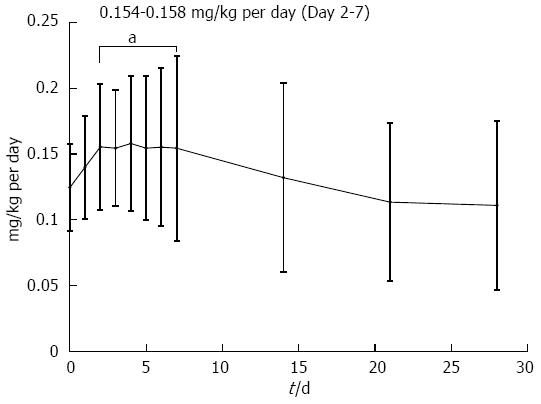

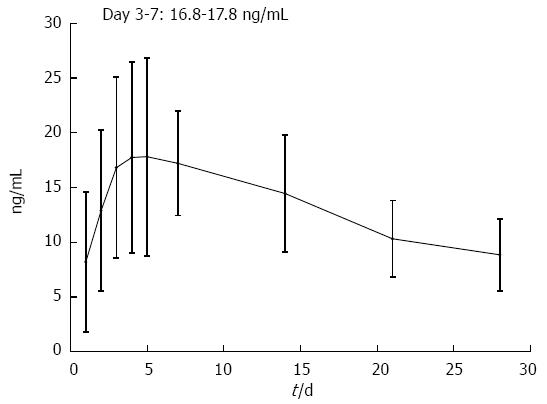

Daily oral tacrolimus dosing was started at 6.47 ± 1.18 mg (0.12 ± 0.03 mg/kg) and significantly increased 1 d after initiation of treatment. From day 2 to day 7, relatively stable tacrolimus doses were required to maintain trough whole-blood levels of 10-15 ng/mL (8.09 ± 3.47 to 8.31 ± 2.64 mg/d and 0.15 ± 0.04 to 0.16 ± 0.05 mg/kg per day) (Figure 1). Mean trough whole-blood levels reached a maximum on day 2 (12.89 ± 7.35 ng/mL) and 93.5% of patients were able to maintain high trough levels (> 10 ng/mL) within the first 7 d of treatment (Figure 2). Mean trough whole-blood levels gradually decreased to 8.85 ± 3.27 ng/mL at day 28.

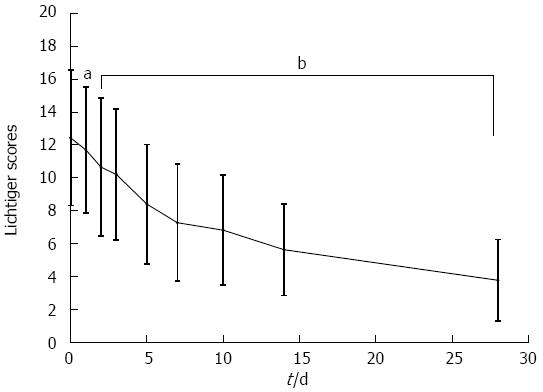

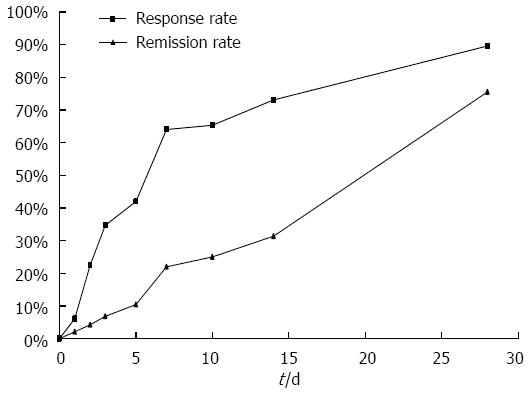

The mean Lichtiger score at the time of treatment initiation was 12.6 ± 3.6. The Lichtiger score decreased significantly beginning 2 d after the initiation of tacrolimus treatment (Figure 3). Two weeks after initiation of therapy, rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus resulted in a clinical response in 73.1% of patients and a clinical remission in 31.4% of patients. Four weeks after initiation of therapy, clinical response and remission were observed in 89.6% and 75.6% of patients, respectively (Figure 4). Within 28 d of tacrolimus treatment, colectomy was required in 3 patients due to their disease becoming refractory to tacrolimus. No significant differences in Lichtiger score, trough levels, clinical response, or clinical remission were observed between patients with steroid-resistant and steroid-dependent UC.

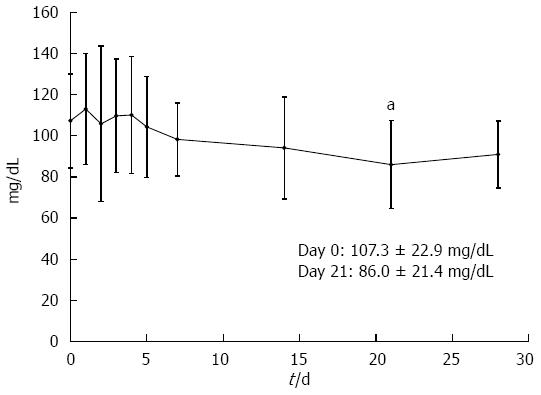

The mean serum creatinine level did not significantly change during tacrolimus treatment. Although 48.6% (18/37) of the patients had at least one elevated glucose (> 120 mg/dL) measured while on tacrolimus treatment, mean fasting blood glucose level was significantly lower at day 21 compared with that on day 0 (86.0 ± 21.4 mg/dL and 107.3 ± 22.9 mg/dL, respectively; P = 0.012) (Figure 5). Other documented clinical reactions and laboratory abnormalities thought to be related to tacrolimus included tremors (35.7%, 15/42), headache (9.5%, 4/42), nausea (7.1%, 3/42), and hypomagnesemia (74.1%, 20/27, 1.56 ± 0.26 mg/dL) (Table 3). Overall, treatment was well tolerated, with no patient requiring treatment disruption or termination due to adverse effects.

| Adverse responses | Value |

| Hypomagnesemia (< 1.7 mg/dL) | 20 (74.1) |

| Elevated blood glucose (> 120 mg/dL) | 18 (48.6) |

| Tremor | 15 (35.7) |

| Headache | 4 (9.5) |

| Nausea | 3 (7.1) |

| Elevated serum creatinine (> 1.2 mg/dL) | 2 (5.4) |

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective multicenter study that has evaluated the effect of rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus in patients with refractory UC. The present results have shown that rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus was well tolerated and yielded a high clinical response rate within 2 wk and a high clinical remission rate within 4 wk after initiation of treatment. These results suggest that rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus should be an option for patients with refractory UC.

Tacrolimus is a macrolide immunosuppressant that is structurally similar to rapamycin and has been found to have potent immunosuppressive properties that are 10- to 100-fold more potent in inhibiting lymphocyte activation than CsA[16-18]. Since less variability in absorption and serum levels is observed among patients treated with tacrolimus compared to those who receive oral CsA, tacrolimus has been suggested to be more easily and safely administered to patients with refractory UC than CsA. Ogata et al[7] conducted the first randomized controlled trial that demonstrated the efficacy of oral tacrolimus in refractory UC patients. A total of 68.4% of patients in the high trough concentration (10-15 ng/mL) group improved within 2 wk after administration of tacrolimus, whereas only 38.1% of patients in the low trough concentration group experienced disease improvement. Thus far, several uncontrolled[15-17,19-21] and two placebo-controlled studies[7,8] have demonstrated that tacrolimus can induce remission in both adults and children, and these reports suggested that tacrolimus had a trough concentration-dependent effect, with the optimal target range appearing to be 10-15 ng/mL with a relatively short period of efficacy. Regarding long-term efficacy in patients with refractory UC, Yamamoto et al[13] investigated the efficacy of tacrolimus as maintenance therapy for patients with refractory UC and reported that the cumulative colectomy-free survival rate was 62% at 65 mo. The colectomy-free survival rate was significantly higher in patients who responded to tacrolimus within 30 d than in those who did not. We previously examined the short-term efficacy of tacrolimus in refractory UC and found that the clinical response rate at 4 wk after initiation of tacrolimus treatment correlated with the mean trough level at 8-21 d after treatment initiation[22]. The primitive trough raised within 5 d after administration is considered to be important for obtaining the appropriate trough level at 8 d after tacrolimus administration. Since oral tacrolimus has a slower onset of action compared to intravenous CsA, and food intake is known to reduce tacrolimus serum trough levels due to its low absorption rate, oral tacrolimus takes more than 7 d to reach high trough levels. Therefore, we have occasionally had severe UC patients who did not demonstrate improvement prior to achieving the appropriate trough level with oral tacrolimus using standard dosing. Indeed, Schmidt et al[23] also evaluated the short-term efficacy of oral tacrolimus in moderate to severe steroid-refractory UC using a starting dose of 0.1 mg/kg per day, and reported that clinical remission was achieved in 52.3% of patients, and 14% of patients required colectomy. In the present study, a high clinical response rate was observed at 2 wk after initiation of treatment (73.1%, 38/52) and a high clinical remission rate was achieved at 4 wk (75.6%, 34/45). Although we cannot directly compare the results of Schmidt et al[23] with those of the present study due to differences in patient baseline characteristics, rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus in the present study appears to yield high remission rates in patients with steroid-refractory UC. Strict dose adjustment of tacrolimus in the early treatment phase has been suggested to provide excellent clinical outcomes and to avoid the need for surgery for refractory UC, because the efficacy of tacrolimus depends on trough blood levels[24]; therefore, we suggest that whole-blood tacrolimus levels should be measured in all patients, and early dose increases should be made as part of rapid induction therapy. In the present study, 0.15-0.16 mg/kg per day of oral tacrolimus was needed to achieve appropriate trough levels; the mean trough level reached high on day 2; and 93.5% of patients could maintain high trough levels within the first 7 d of treatment. Thus far, no studies have evaluated the efficacy of, or dose adjustment for rapid induction therapy with high-dose oral tacrolimus without meals.

Similar to CsA, tacrolimus is known to be associated with many adverse effects, such as infections, renal dysfunction, hypertension, and neurological toxicity. However, these effects are generally mild and reversible. In this study, mean serum creatinine was not significantly elevated during 4 wk of treatment. Interestingly, the mean fasting blood glucose level was significantly lower 21 d after the initiation of treatment as the CAI improved. With regard to other adverse effects, many patients developed hypomagnesemia (74.1%, 1.56 ± 0.26 mg/dL), at a frequency similar to that reported in previous studies (33.3%-87.5%)[7,16]. Although 48.6% (18/37) of the patients had at least one elevated glucose measured during this study, the mean fasting blood glucose level was significantly lower at day 21 compared with that on day 0. Benson also reported that 62.5% of patients had elevated glucose and most of them were on corticosteroid therapy at that time[16]. We therefore consider that it was likely that the hyperglycemia observed was not related to tacrolimus treatment. Tremor appeared to be increased (35.7%) compared with that reported previously (9.4%-19.0%)[7,8,16,25]. However, no significant clinical symptoms were observed during treatment, and no patient discontinued oral tacrolimus therapy due to adverse effects. Thus, we consider that rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus will play a major role in safely inducing remission in patients with refractory UC.

Regarding starting dose of oral tacrolimus and dose adjustment, 29.1%-36.4% of patients needed to do dose adjustment from day 1 to day 4 (data was not shown) and finally daily treatment of oral tacrolimus at dose of 0.15-0.16 mg/kg was needed to achieve appropriate trough levels. Therefore, we consider that oral tacrolimus at an initial dose more than 0.1 mg/kg per day may decrease the number of times of dose adjustment and be more suitable for the patients with refractory UC.

The uncontrolled study design was a limitation of this study. To clarify the efficacy of rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus, further study in which patients are randomized to either rapid induction or standard induction is necessary. Nonetheless, this is the first study to confirm that rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus is a safe and highly effective treatment for patients with refractory UC. Although any long-term effects of this treatment method remain unclear, the rapid induction therapy administered in this study may be useful for the treatment of patients with refractory UC. Further studies are needed to evaluate the long-term outcomes of rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus in patients with UC.

We would like to thank Dr. Takayuki Matsumoto (Division of Lower Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Hyogo College of Medicine, Hyogo, Japan) for his helpful advice.

Tacrolimus has a rapid onset of action and is highly effective in refractory ulcerative colitis (UC) patients. However, the authors have occasionally have had severe UC patients who did not demonstrate improvement prior to achieving the appropriate trough level with oral tacrolimus using standard dosing (0.025 mg/kg twice daily).

Because food intake is known to reduce serum levels of tacrolimus due to its low absorption rate, rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus, starting at 0.1 mg/kg per day without meals should be recommended as a salvage therapy for patients with refractory UC. However, the efficacy and safety of rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus has been unknown.

This is the first prospective multicenter study that has evaluated the effect of rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus in patients with refractory UC. The present results have shown that rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus was well tolerated and yielded a high clinical response/remission rate.

Although any long-term effects of this treatment method remain unclear, the rapid induction therapy administered in this study may be useful for the treatment of patients with refractory UC. The results of this study may help physicians decide how to use oral tacrolimus for the patients with refractory UC.

This is an interesting prospective, multicenter study assessing the efficacy and safety of rapid induction therapy with oral tacrolimus in refractory UC patients.

P- Reviewer: Hiraoka S, Suzuki H S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Hanauer SB. Review article: evolving concepts in treatment and disease modification in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27 Suppl 1:15-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Masson S, Nylander D, Mansfield JC. How important is onset of action in ulcerative colitis therapy? Drugs. 2005;65:2069-2083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Faubion WA, Loftus EV, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The natural history of corticosteroid therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:255-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 833] [Cited by in RCA: 792] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bianchi Porro G, Cassinotti A, Ferrara E, Maconi G, Ardizzone S. Review article: the management of steroid dependency in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:779-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Flanagan WM, Corthésy B, Bram RJ, Crabtree GR. Nuclear association of a T-cell transcription factor blocked by FK-506 and cyclosporin A. Nature. 1991;352:803-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 812] [Cited by in RCA: 854] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bamba S, Tsujikawa T, Sasaki M, Fujiyama Y, Andoh A. Immunomodulators and immunosuppressants for Japanese patients with ulcerative colitis. ISRN Gastroenterol. 2011;2011:194324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ogata H, Matsui T, Nakamura M, Iida M, Takazoe M, Suzuki Y, Hibi T. A randomised dose finding study of oral tacrolimus (FK506) therapy in refractory ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2006;55:1255-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ogata H, Kato J, Hirai F, Hida N, Matsui T, Matsumoto T, Koyanagi K, Hibi T. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral tacrolimus (FK506) in the management of hospitalized patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:803-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Marion JF, Rubin PH, Present DH. Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders 2000; 315-325. |

| 10. | Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625-1629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1958] [Cited by in RCA: 2250] [Article Influence: 59.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gavalas E, Kountouras J, Stergiopoulos C, Zavos C, Gisakis D, Nikolaidis N, Giouleme O, Chatzopoulos D, Kapetanakis N. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:1074-1079. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Van Assche G, D’Haens G, Noman M, Vermeire S, Hiele M, Asnong K, Arts J, D’Hoore A, Penninckx F, Rutgeerts P. Randomized, double-blind comparison of 4 mg/kg versus 2 mg/kg intravenous cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1025-1031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yamamoto S, Nakase H, Mikami S, Inoue S, Yoshino T, Takeda Y, Kasahara K, Ueno S, Uza N, Kitamura H. Long-term effect of tacrolimus therapy in patients with refractory ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:589-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Su C, Lewis JD, Goldberg B, Brensinger C, Lichtenstein GR. A meta-analysis of the placebo rates of remission and response in clinical trials of active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:516-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1970] [Cited by in RCA: 2350] [Article Influence: 123.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 16. | Benson A, Barrett T, Sparberg M, Buchman AL. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus in refractory ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: a single-center experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:7-12. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Högenauer C, Wenzl HH, Hinterleitner TA, Petritsch W. Effect of oral tacrolimus (FK 506) on steroid-refractory moderate/severe ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:415-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gummert JF, Ikonen T, Morris RE. Newer immunosuppressive drugs: a review. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:1366-1380. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Watson S, Pensabene L, Mitchell P, Bousvaros A. Outcomes and adverse events in children and young adults undergoing tacrolimus therapy for steroid-refractory colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:22-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fellermann K, Tanko Z, Herrlinger KR, Witthoeft T, Homann N, Bruening A, Ludwig D, Stange EF. Response of refractory colitis to intravenous or oral tacrolimus (FK506). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8:317-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Inoue T, Murano M, Narabayashi K, Okada T, Nouda S, Ishida K, Kawakami K, Abe Y, Takeuchi T, Tokioka S. The efficacy of oral tacrolimus in patients with moderate/severe ulcerative colitis not receiving concomitant corticosteroid therapy. Intern Med. 2013;52:15-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Murano M, Inoue T, Narabayashi K, Nouda S, Ishida K, Kawakami K, Kuramoto T, Abe Y, Inoue T, Murano N. The safety and efficacy of rapid induction therapy using tacrolimus for severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. Stomach and Intestine. 2011;46:1957-1968. |

| 23. | Schmidt KJ, Herrlinger KR, Emmrich J, Barthel D, Koc H, Lehnert H, Stange EF, Fellermann K, Büning J. Short-term efficacy of tacrolimus in steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis - experience in 130 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:129-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hirai F, Takatsu N, Matsui T. Letter: short-term efficacy of tacrolimus in steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Landy J, Wahed M, Peake ST, Hussein M, Ng SC, Lindsay JO, Hart AL. Oral tacrolimus as maintenance therapy for refractory ulcerative colitis--an analysis of outcomes in two London tertiary centres. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e516-e521. [PubMed] |