Published online Jun 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i23.7297

Peer-review started: January 29, 2015

First decision: February 10, 2015

Revised: February 27, 2015

Accepted: April 28, 2015

Article in press: April 28, 2015

Published online: June 21, 2015

Processing time: 143 Days and 6.4 Hours

AIM: To compare the roles of capsule endoscopy (CE) and double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) in the diagnosis of obscure small bowel diseases.

METHODS: From June 2009 to December 2014, 88 patients were included in this study; the patients had undergone gastroscopy, colonoscopy, radiological small intestinal barium meal, abdominal computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scan and mesenteric angiography, but their diagnoses were still unclear. The patients with gastrointestinal obstructions, fistulas, strictures, or cardiac pacemakers, as well as pregnant women, and individuals who could not accept the capsule-retention or capsule-removal surgery were excluded. Patients with heart, lung and other vital organ failure diseases were also excluded. Everyone involved in this study had undergone CE and DBE. The results were divided into: (1) the definite diagnosis (the diagnosis was confirmed at least by one of the biopsy, surgery, pathology or the drug treatment effects with follow-up for at least 3 mo); (2) the possible diagnosis (a possible diagnosis was suggested by CE or DBE, but not confirmed by the biopsy, surgery or follow-up drug treatment effects); and (3) the unclear diagnosis (no exact causes were provided by CE and DBE for the disease). The detection rate and the diagnostic yield of the two methods were compared. The difference in the etiologies between CE and DBE was estimated, and the different possible etiologies caused by the age groups were also investigated.

RESULTS: CE exhibited a better trend than DBE for diagnosing scattered small ulcers (P = 0.242, Fisher’s test), and small vascular malformations (χ2 = 1.810, P = 0.179, Pearson χ2 test), but with no significant differences, possible due to few cases. However, DBE was better than CE for larger tumors (P = 0.018, Fisher’s test) and for diverticular lesions with bleeding ulcers (P = 0.005, Fisher’s test). All three hemangioma cases diagnosed by DBE in this study (including sponge hemangioma, venous hemangioma, and hemangioma with hamartoma lesions) were all confirmed by biopsy. Two parasite cases were found by CE, but were negative by DBE. This study revealed no obvious differences in the detection rates (DR) of CE (60.0%, 53/88) and DBE (59.1%, 52/88). However, the etiological diagnostic yield (DY) difference was apparent. The CE diagnostic yield was 42.0% (37/88), and the DBE diagnostic yield was 51.1% (45/88). Furthermore, there were differences among the age groups (χ2 = 22.146, P = 0.008, Kruskal Wallis Test). Small intestinal cancer (5/6 cases), vascular malformations (22/29 cases), and active bleeding (3/4 cases) appeared more commonly in the patients over 50 years old, but diverticula with bleeding ulcers were usually found in the 15-25-year group (4/7cases). The over-25-year group accounted for the stromal tumors (10/12 cases).

CONCLUSION: CE and DBE each have their own advantages and disadvantages. The appropriate choice depends on the patient’s age, tolerance, and clinical manifestations. Sometimes CE followed by DBE is necessary.

Core tip: Until now, because of the expensive cost and difficult technology, a study of capsule endoscopy (CE) followed by double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) simultaneously in one case has been rarely reported. To assess the role of CE and DBE in the diagnosis of small bowel diseases, this study was designed to choose the more appropriate examination (between CE and DBE) for obscure small bowel diseases.

- Citation: Zhang ZH, Qiu CH, Li Y. Different roles of capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy in obscure small intestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(23): 7297-7304

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i23/7297.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i23.7297

It is very difficult to diagnose small intestinal diseases because of the specific structure and anatomical location of the small intestine. With the development of capsule endoscopy (CE) and double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) in recent years, the prospect has been brought for the diagnosis and treatment of obscure intestinal diseases. However, until now, because of the expensive cost and difficult technology, studies of CE followed by DBE simultaneously in one case have been rare.

To assess the role of CE and DBE in the diagnosis of small bowel diseases, 88 patients were collected in our hospital from June 2009 to December 2014. The purpose of this study was to provide more information for choosing the more appropriate examination for obscure small bowel diseases.

Eighty-eight patients who underwent CE followed by DBE were enrolled in our hospital from June 2009 to December 2014. The ratio of males to females was 64 to 24, with an average age of 47.19 years (range from 16 years to 78 years). The duration of symptoms ranged from 1 wk to 180 mo. The number of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) cases was 70, and the number of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and abdominal discomfort cases was 18.

All patients underwent gastroscopy and colonoscopy, and some of them were given a radiological small intestinal barium meal, an abdominal computed tomography (CT) or a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, mesenteric angiography or other procedures. However, the causes of them were still not clear.

Contraindications to CE, such as gastrointestinal obstructions, fistulas, strictures, cardiac pacemakers, pregnant women, and patients who could not accept the capsule retention or capsule removal surgery, were excluded.

The contraindications to DBE still included heart, lung and other vital organ failure diseases. Informed consent was obtained from the patients before the procedures were performed.

CE procedure: All of the patients underwent the Pill Cam SB capsule procedure (GIVEN imaging, Israel). Before the procedure, the patients prepared their bowels with 3 liters of PEG (2 liters at 10:00 pm the night before the procedure, and 1 liter with the simethicone at 4:00 am on the morning of the procedure). The procedure was usually halted when the arrival of ileocecus was confirmed by the monitor 8-10 h later; otherwise, the procedure was continued until the next morning. The image was reviewed by two independent experienced reviewers. During the procedure, exposure to electromagnetic fields was avoided.

DBE procedure: The Fuji DBE system (Japan) was used. The antegrade DBE required the patients to fast for 6-8 h, and the retrograde DBE required bowel preparation with 2 L of PEG. Conscious sedation (including 10 mg im diazepam, 100 mg im pethidine, and 10 mg im alisodamine) was performed before the procedure. The tip of the small intestinal endoscope and the overtube were inserted into the duodenum or ileum. The overtube was inflated and fixed to the small intestine, and then the endoscope was advanced until it could not continue. After the balloon was inflated and fixed, the empty overtube was inserted into the endoscopic tip and then inflated. The endoscopy and overtube were slowly straightened. The oral and anal procedures were marked by tattooing with a spot, if necessary.

The definite diagnosis: The diagnosis was confirmed at least by one of biopsy, surgery, pathology or the follow-up drug treatment effects.

The possible diagnosis: A possible diagnosis was suggested by CE or DBE, but not confirmed by the biopsy, surgery, or follow-up drug treatment.

The unclear diagnose: No exact causes of the diseases were revealed by CE and DBE.

The SPSS 15.0 statistical analysis software was applied. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Assistant Professor Quan Ting from the Department of Clinical Trial Statistics in the Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital.

Detection rate = positive detected cases/all cases × 100%

Diagnostic yield = definitely diagnosed cases/all cases × 100%

All data were statistically analyzed by Fisher’s test, Fisher’s exact test, Pearson’s χ2 test, and the Kruskal-Wallis test, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

CE: Eighty-six cases of CE successfully passed through the esophagus to the stomach (accounting for 97.7%, 86/88), and only two were delayed in the stomach for more than four hours and then were passed into the duodenum using a gastroscope. Sixty to three hundred minutes (average 256 min) were spent by CE to pass through the entire small intestine without any discomfort. One capsule remained and was removed by surgery two weeks later.

DBE: The mean duration for the antegrade DBE was approximately 56 min (40-80 min), and the mean length of insertion was 130-450 cm. For the retrograde DBE, the duration was 70 min (40-100 min) and the length was 40-260 cm. Two cases of failure by DBE were subsequently identified as terminal ileum cancer.

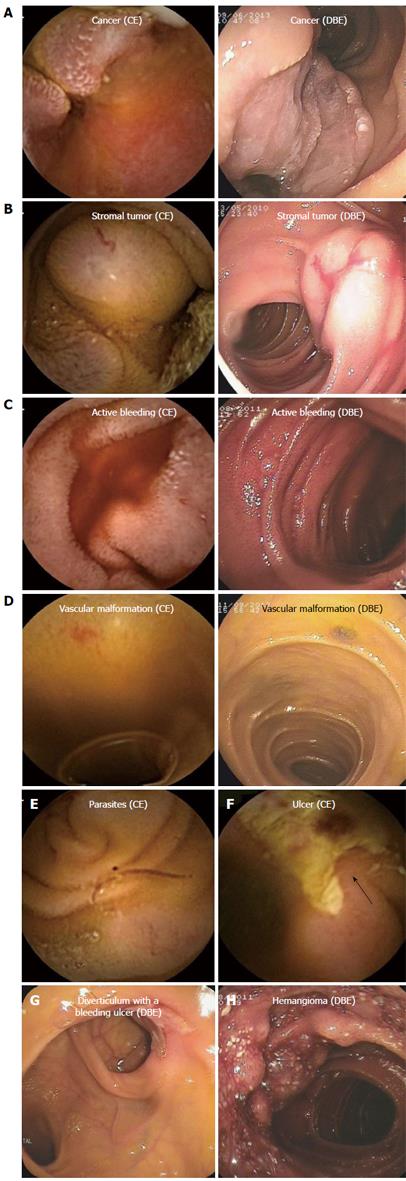

Diagnostic yield (62/88 cases): As presented in Table 1, CE exhibited a better trend than DBE for diagnosing the scattered small ulcers (P = 0.242, Fisher’s test), and small vascular malformations (χ2 = 1.810, P = 0.179, Pearson χ2 test), but with no significant difference. However, DBE was superior to CE for larger tumors (P = 0.018, Fisher’s test) and for diverticular lesions with bleeding ulcers (P = 0.005, Fisher’s test). In this study, the latter was almost misdiagnosed except for one case undergoing CE. Furthermore, all three hemangioma cases diagnosed by DBE in this study (including sponge hemangioma, venous hemangioma, and hemangioma with hamartoma lesions) were all confirmed by biopsy. Later, the three cases of CE images were again reviewed, and it was found that one case was misdiagnosed and that the other two cases were misdiagnosed as a protuberant lesion and active bleeding. Two parasite cases were found by CE but were negative by DBE. However, because the cases of hemangioma and parasites were very few, it was difficult to perform a statistical analysis (Figure 1).

Possible but not-confirmed cases (18) and not-confirmed cases (8): As shown in Table 2, CE was superior to DBE for diagnosing active bleeding, vascular malformation and submucosal bulges, but the differences were not significant (P = 0.429, 0.170, and 0.143, respectively).

| Etiology (cases) | Active bleeding (4) | Vascular malformations (10) | Submucosal bulge (4) |

| CE(+) | 4 | 8 | 4 |

| CE(-) | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| DBE(+) | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| DBE(-) | 2 | 6 | 3 |

| P value | 0.429 | 0.170 | 0.143 |

Detection rate and diagnostic yield: In this study, there was no obvious difference between CE and DBE for the DR. The CE detection rate was 60.0% (53/88), and the DBE detection rate was 59.1% (52/88). However, the etiological DY difference between the two was apparent. The CE diagnostic yield was 42.0% (37/88), and the DBE diagnostic yield was 51.1% (45/88).

Impact of age on etiology: According to the age groups, the data were classified as presented in Table 3. In sum, there were differences among the age groups (χ2 = 22.146, P = 0.008, Kruskal-Wallis test). Small intestinal cancers (5/6 cases), vascular malformations (22/29 cases), and active bleeding (3/4 cases) appeared more common in the aged patients over 50 years old, but the diverticula with bleeding ulcers were usually found in the 15-25-year group (4/7 cases). The over-25-year group accounted for the stromal tumors (10/12 cases).

| Etiology | 15-25 yr | 25-50 yr | >50 yr |

| (cases) | 16 | 22 | 41 |

| Ulcer | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Small intestinal | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| cancer | |||

| Stromal tumor | 2 | 5 | 5 |

| Inflammatory hyperplasia or polyps | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Vascular malformations | 2 | 5 | 22 |

| Active bleeding | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Diverticulum with a bleeding ulcer | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Hemangioma | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Parasites | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Submucosal bulge? | 1 | 2 | 1 |

(1) Ulcers: CE usually showed part of the lesions, but DBE did the whole appearance; (2) small intestinal tumors: From the different angle, different manifestations were showed by CE and DBE. Sometimes, the difference was big; (3) active bleeding: In most conditions, CE showed the positive active bleeding appearance. However, DBE just for few cases; (4) inflammatory hyperplasia or polyps: DBE could show the positive result by biopsy. However, CE just gave some possible diagnoses, especially for adenoma or simple hyperplasia polyps; (5) vascular malformations and hemangiomas: CE could show vascular malformations clearly. However, hemangiomas were often identified by biopsy of DBE; and (6) diverticula with bleeding ulcers: It was difficult for CE to diagnose (Figure 1).

CE and DBE have brought many prospects for diagnosing and treating intestinal diseases. According to previous research, CE accounts for 56%-70% of small intestinal bleeding disorders[1], whereas the definite diagnostic yield is only 20%-30%[2,3]. DBE accounts for 60%-70% of the diagnostic yield for intestinal diseases[4,5]. Therefore, there are still flaws in the diagnoses of obscure small intestinal diseases. In this study, the advantages and disadvantages of examinations were reevaluated using CE followed by DBE in the same case, and the results were expected to provide more information for future clinical choices.

CE has its unique advantages, such as convenience, non-invasiveness, security, visibility, and comfortableness. This study confirmed its advantages. First, it is much easier for CE to diagnose scattered, small and multiple lesions than single and larger lesions. In this study, CE accounted for 83.3% of 0.2-2 cm diameter multiple scattered small ulcers, and 73.7% of the enlarged vascular malformations and small-mass blue venous angiomas; by contrast, DBE only accounted for 33.3% of ulcers and 52.6% of vascular malformations, which demonstrated a better trend for CE than DBE. However, the difference was not statistically significant, possibly due to the few cases. Second, the completion rate of CE was 97.7% without any assistance, but the completion rate of DBE was only 1.14% in this study, which accounted for the lower missing diagnostic rate for CE. The lower completion rate of DBE was due to the DBE technical difficulties, which made the completion rate of DBE lower (5.5%-20%) than that in the previous study[6]. In particularly, it was sometimes difficult for the retrograde DBE to be intubated from the ileocecal valve[7,8]. In this study, two lesions located in the terminal ileum were missed by DBE because of the retrograde endoscope intubation failure. Third, it seemed easier to diagnose active bleeding by CE than by DBE (100% vs 50%), but there was no significant difference, which implied that more cases may be necessary in the future. Previous studies have demonstrated that the CE etiology detection rate of active bleeding may be improved if an appropriate opportunity is chosen[9-11]. During the early bleeding stage (87%) and the overt stage (56%), CE yielded a higher positive ratio (87% and 56%) than the occult or bleeding-cessation stage (12.9%)[12,13]. In addition, in this study, the detection ratio of the blood clots by CE was higher than that by DBE (25% vs 0%), which was also consistent with a previous study[14]. Furthermore, even if the definite bleeding cause was not revealed by CE for the first time, some useful information about the bleeding site or single or multiple lesions might be provided by CE for the later performance of a surgical procedure or other treatment. Choosing an appropriate occasion for rechecking by CE might facilitate finding the missed lesions and improving the diagnostic yield[15,16].

Although CE is considered to have the irreplaceable advantages, it still has some disadvantages. First, the CE observation cannot be repeated, the direction and speed of movement are uncontrolled, the images are transient and random, and the quality of the CE image is easily affected by the intestinal canal cleanness and the speed of GI tract movement. In addition, the risk of retention is still present, although the incidence is low (1.5% to 5%)[17,18].Therefore, the retention risk should be assessed and informed to the patients before the procedure[19,20]. Second, it is difficult for CE to differentiate the elevated sub-mucosal lesions without erosions or ulcers on the surface from the external pressure[21,22]. At that time, DBE is usually necessary to differentiate the lesions. Third, for the larger tumors over 1/2 cavity, such as the cancers or stromal tumors with erosive lesions, the erosive lesions are easy to be misdiagnosed as local inflammation and the tumors are missed[23,24]. Fourth, it is occasionally difficult for CE to identify the lesion’s position accurately, especially when CE fails to access the ileocecum. In this study, one lesion’s position was misdiagnosed in the lower segment of jejunum and was confirmed in the duodenum’s horizontal section by the later operation.

Compared with CE, the DBE procedure is more uncomfortable and less tolerated. In this study, the male-to-female ratio was 2.6 to 1, and the lower completion rate of DBE led to a much higher misdiagnosis rate. The lower completion ratio of DBE led to the lower detection rate of the active bleeding lesions, parasites, vascular malformations, etc. Moreover, the intestinal mucosal folds made some lesions difficult to be observed by DBE. In addition, the bleeding and perforation complications (3.8%-4.3%)[25,26] still make the DBE procedure more complex and difficultly popular. However, DBE has some advantages, such as direct and repeated observation, stainability, biopsy and polypectomy, etc.[27-29]. For the larger diverticula with bleeding ulcers, DBE was better than CE. In our study, 7 cases with diverticula were identified by DBE (7.95%, 7/88), but for CE, the percentage was 1.14% (1/88), which was consistent with previous reports (CE 0.6% vs DBE 3.97%)[6,14]. It is suggested that DBE can avoid some defects of CE, such as the limited observation angle and the nondilated lumen. Additionally, in this study, the detection rates for CE and DBE were similar (60.0% vs 59.1%), but the diagnostic yield ratios of CE and DBE were 42% vs 51.1%. Compared with the previously report, the etiological diagnosis rate of 69%-75% for DBE was lower in this research[30,31]. The possible reason was the few cases, which might have caused bias. Additional cases may help to elucidate this finding in the future.

In conclusion, there are many advantages and disadvantages for CE and DBE, in small intestinal disease diagnosis. Sometimes, it is better to obtain an overall observation by CE firstly and then decide whether DBE is necessary for the further examination.

It is very difficult to diagnose small intestinal diseases because of the small intestine’s specific structure and anatomical location. With the development of capsule endoscopy (CE) and double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) in recent years, the prospect has been raised for diagnosing and treating obscure intestinal diseases. However, because of the expensive cost and difficult technology, studies involving CE followed by DBE simultaneously in one case have been rare. Therefore, this study was designed to provide suggestions for choosing the better examination.

According to the previous research, CE accounts for 56%-70% of small intestinal bleeding disorders, whereas the definite diagnostic yield is only 20%-30%. DBE accounts for 60%-70% of the diagnostic yield of intestinal diseases. Consequently, by now, there are still flaws in the diagnosis of obscure small intestinal diseases. However, when and how to choose the appropriate examination is the key.

Until now, because of the expensive cost and difficult technology, studies of CE followed by DBE simultaneously in one case have been rare. The present investigation was designed to reevaluated the advantages and disadvantages of the two methods in the same case and was expected to provide more information for future clinical choices. This study revealed that some lesions were more easily diagnosed by CE, such as scattered, small and multiple lesions and active bleeding. Larger diverticula with bleeding ulcers and large submucosa lesions were better diagnosed by DBE.

Until now, because of the expensive cost and difficult technology, there are still flaws in the diagnosis of obscure small intestinal diseases. In the future, as research continues to foster an in-depth understanding, increasingly more intestinal diseases will be diagnosed accurately and easily.

On some occasions, the diagnosis of small diseases was very difficult. With the development of CE and DBE in recent years, the prospect has been raised for diagnosing and treating obscure intestinal diseases. The appropriate choice would depend on age, tolerance and clinical manifestations. Furthermore, CE followed by DBE is sometimes necessary.

This is a very good study; the author compared the effects of CE and DBE in diagnosing small intestinal diseases in the same case. These study results are helpful for patients and clinicians to choose suitable methods for obscure small intestinal diseases.

P- Reviewer: Leitman M, Nomura S S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Nadler M, Eliakim R. The role of capsule endoscopy in acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2014;7:87-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Triester SL, Leighton JA, Leontiadis GI, Fleischer DE, Hara AK, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to other diagnostic modalities in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2407-2418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 433] [Cited by in RCA: 419] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | de Leusse A, Vahedi K, Edery J, Tiah D, Fery-Lemonnier E, Cellier C, Bouhnik Y, Jian R. Capsule endoscopy or push enteroscopy for first-line exploration of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding? Gastroenterology. 2007;132:855-862; quiz 1164-1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Domagk D, Mensink P, Aktas H, Lenz P, Meister T, Luegering A, Ullerich H, Aabakken L, Heinecke A, Domschke W. Single- vs. double-balloon enteroscopy in small-bowel diagnostics: a randomized multicenter trial. Endoscopy. 2011;43:472-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Teshima CW, Kuipers EJ, van Zanten SV, Mensink PB. Double balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: an updated meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:796-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kamalaporn P, Cho S, Basset N, Cirocco M, May G, Kortan P, Kandel G, Marcon N. Double-balloon enteroscopy following capsule endoscopy in the management of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: outcome of a combined approach. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:491-495. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Tsujikawa T, Saitoh Y, Andoh A, Imaeda H, Hata K, Minematsu H, Senoh K, Hayafuji K, Ogawa A, Nakahara T. Novel single-balloon enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of the small intestine: preliminary experiences. Endoscopy. 2008;40:11-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Takano N, Yamada A, Watabe H, Togo G, Yamaji Y, Yoshida H, Kawabe T, Omata M, Koike K. Single-balloon versus double-balloon endoscopy for achieving total enteroscopy: a randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:734-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ciobanu L, Pascu O, Diaconu B, Matei D, Pojoga C, Tanţău M. Bleeding Dieulafoy’s-like lesions of the gut identified by capsule endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4823-4826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Riccioni ME, Urgesi R, Cianci R, Rizzo G, D’Angelo L, Marmo R, Costamagna G. Negative capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding reliable: recurrence of bleeding on long-term follow-up. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4520-4525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Heo HM, Park CH, Lim JS, Lee JH, Kim BK, Cheon JH, Kim TI, Kim WH, Hong SP. The role of capsule endoscopy after negative CT enterography in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Eur Radiol. 2012;22:1159-1166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Carey EJ, Leighton JA, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK, Post JK, Fleischer DE. A single-center experience of 260 consecutive patients undergoing capsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:89-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pennazio M, Santucci R, Rondonotti E, Abbiati C, Beccari G, Rossini FP, De Franchis R. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after capsule endoscopy: report of 100 consecutive cases. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:643-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 637] [Cited by in RCA: 604] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhang Q, He Q, Liu J, Ma F, Zhi F, Bai Y. Combined use of capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy in the diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: meta-analysis and pooled analysis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:1885-1891. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Tae CH, Shim KN. Should capsule endoscopy be the first test for every obscure gastrointestinal bleeding? Clin Endosc. 2014;47:409-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rahmi G, Samaha E, Vahedi K, Delvaux M, Gay G, Lamouliatte H, Filoche B, Saurin JC, Ponchon T, Rhun ML. Long-term follow-up of patients undergoing capsule and double-balloon enteroscopy for identification and treatment of small-bowel vascular lesions: a prospective, multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2014;46:591-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sears DM, Avots-Avotins A, Culp K, Gavin MW. Frequency and clinical outcome of capsule retention during capsule endoscopy for GI bleeding of obscure origin. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:822-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kopylov U, Seidman EG. Role of capsule endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1155-1164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zagorowicz ES, Pietrzak AM, Wronska E, Pachlewski J, Rutkowski P, Kraszewska E, Regula J. Small bowel tumors detected and missed during capsule endoscopy: single center experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:9043-9048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cangemi DJ, Patel MK, Gomez V, Cangemi JR, Stark ME, Lukens FJ. Small bowel tumors discovered during double-balloon enteroscopy: analysis of a large prospectively collected single-center database. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:769-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nakatani M, Fujiwara Y, Nagami Y, Sugimori S, Kameda N, Machida H, Okazaki H, Yamagami H, Tanigawa T, Watanabe K. The usefulness of double-balloon enteroscopy in gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the small bowel with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Intern Med. 2012;51:2675-2682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chen WG, Shan GD, Zhang H, Li L, Yue M, Xiang Z, Cheng Y, Wu CJ, Fang Y, Chen LH. Double-balloon enteroscopy in small bowel tumors: a Chinese single-center study. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3665-3671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | He Q, Bai Y, Zhi FC, Gong W, Gu HX, Xu ZM, Cai JQ, Pan DS, Jiang B. Double-balloon enteroscopy for mesenchymal tumors of small bowel: nine years’ experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1820-1826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Mensink PB, Haringsma J, Kucharzik T, Cellier C, Pérez-Cuadrado E, Mönkemüller K, Gasbarrini A, Kaffes AJ, Nakamura K, Yen HH. Complications of double balloon enteroscopy: a multicenter survey. Endoscopy. 2007;39:613-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tomba C, Elli L, Bardella MT, Soncini M, Contiero P, Roncoroni L, Locatelli M, Conte D. Enteroscopy for the early detection of small bowel tumours in at-risk celiac patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:400-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ohmiya N, Nakamura M, Tahara T, Nagasaka M, Nakagawa Y, Shibata T, Hirooka Y, Goto H, Hirata I. Management of small-bowel polyps at double-balloon enteroscopy. Ann Transl Med. 2014;2:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Neely D, Ong J, Patterson J, Kirkpatrick D, Skelly R. Small intestinal adenocarcinoma: rarely considered, often missed? Postgrad Med J. 2013;89:197-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | He Q, Zhang YL, Xiao B, Jiang B, Bai Y, Zhi FC. Double-balloon enteroscopy for diagnosis of Meckel’s diverticulum: comparison with operative findings and capsule endoscopy. Surgery. 2013;153:549-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Cazzato IA, Cammarota G, Nista EC, Cesaro P, Sparano L, Bonomo V, Gasbarrini GB, Gasbarrini A. Diagnostic and therapeutic impact of double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) in a series of 100 patients with suspected small bowel diseases. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:483-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Rahmi G, Samaha E, Vahedi K, Ponchon T, Fumex F, Filoche B, Gay G, Delvaux M, Lorenceau-Savale C, Malamut G. Multicenter comparison of double-balloon enteroscopy and spiral enteroscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:992-998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |