Published online Jun 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i23.7289

Peer-review started: September 18, 2014

First decision: October 29, 2014

Revised: January 5, 2014

Accepted: February 5, 2015

Article in press: February 5, 2015

Published online: June 21, 2015

Processing time: 275 Days and 18.6 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the safety and efficacy of endoscopic papillary large balloon dilatation (EPLBD) without endoscopic sphincterotomy in a prospective study.

METHODS: From July 2011 to August 2013, we performed EPLBD on 41 patients with naïve papillae prospectively. For sphincteroplasty of EPLBD, endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) was not performed, and balloon diameter selection was based on the distal common bile duct diameter. The balloon was inflated to the desired pressure. If the balloon waist did not disappear, and the desired pressure was satisfied, we judged the dilatation as complete. We used a retrieval balloon catheter or mechanical lithotripter (ML) to remove stones and assessed the rates of complete stone removal, number of sessions, use of ML and adverse events. Furthermore, we compared the presence or absence of balloon waist disappearance with clinical characteristics and endoscopic outcome.

RESULTS: The mean diameters of the distal and maximum common bile duct were 13.5 ± 2.4 mm and 16.4 ± 3.1 mm, respectively. The mean maximum transverse-diameter of the stones was 13.4 ± 3.4 mm, and the mean number of stones was 3.0 ± 2.4. Complete stone removal was achieved in 97.5% (40/41) of cases, and ML was used in 12.2% (5/41) of cases. The mean number of sessions required was 1.2 ± 0.62. Pancreatitis developed in two patients and perforation in one. The rate of balloon waist disappearance was 73.1% (30/41). No significant differences were noted in procedure time, rate of complete stone removal (100% vs 100%), number of sessions (1.1 vs 1.3, P = 0.22), application of ML (13% vs 9%, P = 0.71), or occurrence of pancreatitis (3.3% vs 9.1%, P = 0.45) between cases with and without balloon waist disappearance.

CONCLUSION: EST before sphincteroplasty may be unnecessary in EPLBD. Further investigations are needed to verify the relationship between the presence or absence of balloon waist disappearance.

Core tip: Optimal approaches to sphincteroplasty of endoscopic papillary large balloon dilatation (EPLBD) remain controversial. We evaluated sphincteroplasty in EPLBD. Forty-one patients with naïve papillae received EPLBD. During sphincteroplasty of EPLBD, endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) was not performed. Complete stone removal, number of sessions, use of mechanical lithotripter (ML), and adverse events were assessed. Complete stone removal was achieved in 97.5% of cases, and ML was used in 12.2% of cases. The mean number of sessions required was 1.2 ± 0.62. Pancreatitis developed in two patients and perforation in one. EST before sphincteroplasty may be unnecessary in EPLBD.

- Citation: Omuta S, Maetani I, Saito M, Shigoka H, Gon K, Tokuhisa J, Naruki M. Is endoscopic papillary large balloon dilatation without endoscopic sphincterotomy effective? World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(23): 7289-7296

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i23/7289.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i23.7289

Endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) and endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation (EPBD) are well-established therapies to treat bile duct stones[1-6]. However, the removal of multiple stones; large stones; barrel-shaped or tapering stones; or retrieving any size or shape of stone through a tortuous distal common bile duct, remains difficult[7]. Ersoz et al[8] first reported the utility of endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation (EPLBD) to remove large bile duct stones, with a number of subsequent studies reporting the efficacy and safety of the procedure[8-26]. However, opinions differ on whether or not to use an EST incision and the degree of such an incision (small, moderate or large). Meanwhile balloon selection and dilation techniques have been widely discussed[8-11,13-18,22-26]. For example, Jeong et al[16] reported that EPLBD using a large size balloon (15-18 mm) without EST was both effective and safe. However, given that few other studies have been conducted to verifying the utility of this technique[16,23,25,26], we sought to corroborate the results. In the present study, during sphincteroplasty of EPLBD, EST was not performed. Furthermore, we improved the dilatation technique to make it as minimal as possible.

The study participants comprised 41 consecutive patients who underwent EPLBD at Toho University Ohashi Medical Center from July 2011 to September 2013. The inclusion criteria were as follows: successful selective biliary cannulation; distal common bile duct ≥ 11 mm in diameter or large bile duct stones (≥ 10 mm in diameter); multiple stones (n > 2); and post-gastric reconstruction (Billroth I or II or Roux-en-Y).

The exclusion criteria were as follows: coagulopathy (international normalized ratio ≥ 1.5; marked thrombocytopenia (platelets < 50000/mL); need for precutting to achieve selective biliary cannulation; acute cholangitis or pancreatitis; previous EST; distal common bile duct > 21 mm in diameter; benign or malignant biliary stricture; or failure to give informed consent to the procedure.

All anticoagulant and antiplatelet drugs were discontinued before the procedure, with temporary heparin substitution as necessary. All patients were sedated via intravenous administration of midazolam (5-10 mg). Scopolamine butyl bromide (20 mg) or glucagon (1 mg) was injected intravenously to inhibit gastrointestinal peristalsis, and each patient received nafamostatmesilate (20 mg/d) for one day before endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Blood samples collected 2 h after ERCP were used to determine complete blood counts and serum amylase levels; those collected 18-24 h after were used to measure hepatobiliary enzymes and C-reactive protein. We did not place a pancreatic duct stent to prevent pancreatitis.

The protocol adhered to the Helsinki Declaration and was approved in advance by the Institutional Ethical Review Board. The trial was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN0000011533). All participants gave written, informed consent beforehand.

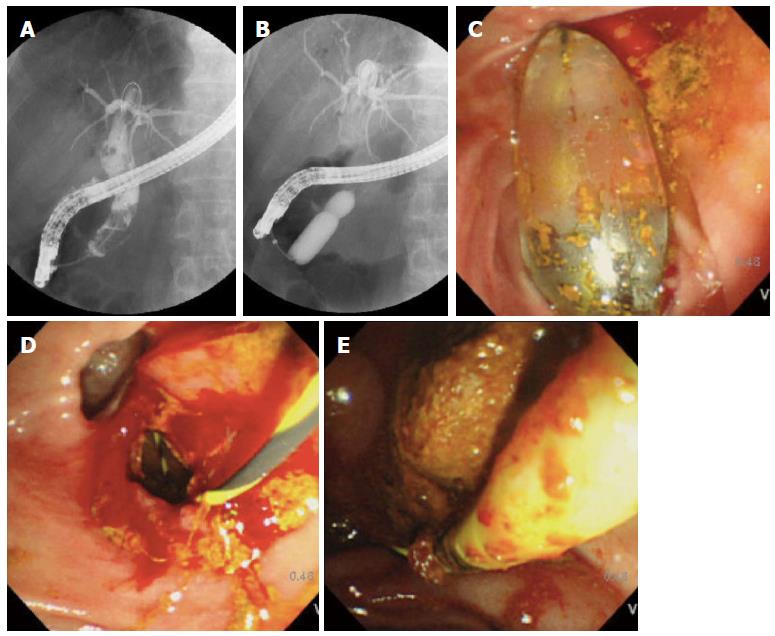

EPLBD was performed using endoscopes (JF-260V™; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan, or ED-530XT8™; Fujinon, Tokyo, Japan), and balloons of 5.5 cm in length and 10-12, 12-15, 15-18, or 18-20 mm in diameter (CRE esophageal/pyloric balloon™; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, United States) were used for dilatation. The pressure was 10-11-12 mm: 3-5-8 atm, 12-13.5-15 mm: 3-4.5-8 atm, 15-16.5-18 mm: 3-4.5-7 atm, 18-19-20 mm: 3-4.5-6 atm, respectively. All ERCPs were performed by an endoscopist with career experience of over 500 ERCPs (Maetani I, Shigoka H or Omuta S). After accessing the major papilla, the bile duct was cannulated by a wire-guided cannulation technique using a catheter (Tandem XL™, Boston Scientific, Natick MA, United States). A cholangiogram was obtained and used to measure the diameter of the distal common bile duct and stones, correcting for magnification with the external diameter of the distal end of the duodenoscope (JF 260V: 11.3 mm/ED-530XT8: 11.5 mm) as a reference (Figure 1).

Balloon diameter selection was determined based on previously described distal common bile duct diameter. For example, for 15-mm, we selected a 15-18 mm balloon to obtain a larger opening of the orifice. After removal of the catheter, the balloon was passed over the guidewire and positioned across the major papilla. An assisting endoscopist gradually performed dilatation under endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance, using diluted contrast to inflate the balloon.

Inflation of the balloon was done until the desired pressure was achieved. If the balloon waist did not disappear, and the desired pressure was satisfied, we judged the dilatation as complete.

When possible, stones were removed using a retrieval balloon (Fusion Quattro™, Cook Medical, Tokyo Japan). When stone removal was not possible with a retrieval balloon, a mechanical lithotripter (ML) (Trapezoid™; Boston Scientific) was used to crush and capture the stones. Within a few days of initial EPLBD, a follow-up cholangiogram was obtained to assess the presence of residual stones. If residual stones were detected, a second ERCP session was performed to remove them without an additional sphincteroplasty. Each ERCP session was finished within 60 min.

The primary study endpoint was the rate of complete stone removal. Secondary endpoints were number of ERCP sessions needed, rate of application of ML, and adverse events, such as post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP), bleeding, cholangitis or perforation within 72 h after EPLBD.

For subgroup analysis, we compared the presence or absence of balloon waist disappearance with clinical characteristics and endoscopic outcome. Complete stone removal was defined as the absence of any filling defect during a final cholangiogram performed endoscopically or through a nasobiliary drainage catheter. PEP was defined as continued abdominal pain ≥ 24 h after ERCP, with a serum amylase level more than three times the upper limit of normal[27]. Bleeding was defined as either or both hematemesis or a melena or a hemoglobin drop exceeding 2g[27]. Cholangitis was defined as increased temperature (over 38 °C for > 24 h) with cholestasis[27]. Perforation was defined as evidence of air or luminal contents outside the gastrointestinal tract[27]. Each adverse event was graded based on values set by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE)[27].

Data were presented as mean ± SD with ranges. In subgroup analyses, the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test were used for noncontinuous variables and Student’s t-test was used for continuous variable comparison between two groups. Analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL, United States). A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Baseline characteristics and indications of the 41 consecutive patients enrolled in this study are summarized in Table 1. The EPLBD procedure was successfully performed in all patients. Two post-gastric reconstruction patients had undergone a Billroth-II, and one had undergone a Roux-en-Y. A periampullary diverticulum was observed 68.3% (28/41). The mean diameter of the distal/maximum common bile duct was 13.5 ± 2.4 mm/16.4 ± 3.1 mm. The mean maximum transverse-diameter of the stones was 13.4 ± 3.4 mm, and the mean number of stones was 3.0 ± 2.4. Endoscopic outcomes are summarized in Table 2. Complete stone removal was achieved in 97.5% of patients (40/41), with a successful stone removal rate during the initial EPLBD of 87.8% (36/41). Thirteen patients required a second session, and one patient required a third session. The mean number of sessions required for complete stone removal was 1.2 ± 0.62. The rate of application of ML was 12.2% (5/41), and the rate of balloon waist disappearance was 73.1% (30/41).

| Age (yr) | 77.7 ± 10.8 |

| Gender ratio (M:F) | 19:22 |

| Periampullary diverticulum | 28 (68.3) |

| Previous gastric surgery | 3 (7.3) |

| Billroth II/Roux-en-Y reconstruction, n | 2/1 |

| Previous cholecystectomy | 12 (29.2) |

| Gallbladder stone | 18 (43.9) |

| Anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy | 19 (46.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (7.3) |

| CBD diameter (distal/maximum) (mm) | 13.5 ± 2.4/16.4 ± 3.1 |

| CBD stone diameter (maximum transverse) (mm) | 13.4 ± 3.4 |

| Number of stones | 3.0 ± 2.4 |

| Balloon size | |

| 10-12 mm/12-15 mm/15-18 mm/18-20 mm | 10/20/8/3 |

| Distal CBD (balloon diameter)/CBD stone ratio | 1.03 ± 0.15 |

| Maximum CBD/CBD stone ratio | 1.25 ± 0.19 |

| Waist disappearance | 30/41 (73.1) |

| Procedure time (min) | 44.5 ± 21.2 |

| Complete stone removal | 40/41 (97.5) |

| Sessions required for complete stone removal | 1.2 ± 0.62 |

| Application of ML | 5/41 (12.2) |

| Amylase after EPLBD (IU/L) | 427 ± 695 |

Adverse events are shown in Table 3. Mild PEP occurred in two patients (4.9%): both were managed successfully with conservative treatment. Perforation developed in one patient who had undergone post-gastric reconstruction (Billroth-II) and did not have a stricture of the distal common bile duct; the balloon waist s disappeared immediately during balloon dilatation. The patient required emergency surgery and stayed in the hospital for six months. After the patient’s condition improved, complete stone removal was achieved using only a retrieval balloon catheter without an additional sphincteroplasty.

| Early (< 72 h) | |

| Asymptomatic hyperamylasemia | 2/41 (4.9) |

| Acute pancreatitis | 2/41 (4.9) |

| Mild/moderate/severe | 2/0/0 |

| Bleeding | 0/41 (0) |

| Acute cholangitis | 0/41 (0) |

| Perforation | 1/41 (2.4) |

On comparing clinical characteristics and endoscopic outcomes with the presence or absence of balloon waist disappearance (Table 4), no significant differences were noted for distal common bile duct diameter, procedure time, mean number of sessions required for complete stone removal, application of ML or occurrence of PEP.

| Variables | Waist disappearance(n = 30) | Waist non-disappearance(n = 11) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 77.7 ± 10.8 | 77.5 ± 11.4 | NS |

| Gender (M:F) | 15:15 | 4:7 | NS |

| Periampullary diverticulum | 70% (21/30) | 63.6% (7/11) | NS |

| Distal CBD diameter (mm) | 13.0 ± 2.1 | 14.8 ± 2.9 | NS |

| Distal CBD diameter/stone ratio | 1.05 ± 0.13 | 1.00 ± 0.21 | NS |

| Number of stones | 2.8 ± 2.2 | 3.6 ± 2.7 | NS |

| Procedure time (min) | 43 ± 20 | 49 ± 24 | NS |

| Sessions required for complete stone clearance | 1.1 ± 0.86 | 1.3 ± 0.43 | NS |

| Application of ML | 13.3% (4/30) | 9.1% (1/11) | NS |

| Acute pancreatitis | 3.3% (1/30) | 9.1% (1/11) | NS |

Ersoz et al[8] first reported the use of endoscopic sphincterotomy followed by large balloon dilation as an alternative for managing difficult bile duct stones. Their reported overall complete stone removal rate was 100%, with ML application used in 7% and an overall adverse event rate of 15%, including a 3% PEP rate. EPLBD without preceding EST was described in 2009 by Jeong et al[16], who reported an overall complete stone removal rate of 97%, with a 21% rate of ML application and a 2.6% PEP rate. A summary of the English-language literature published on EPLBD is shown in Table 5. We conducted research on PubMed/MEDLINE from 2003 to October 2014. A search strategy was used to identify reports of randomized controlled trials, retrospective studies and prospective case series in EPLBD, with a combination of controlled vocabulary and text words related to (1) endoscopic papillary large balloon dilatation; (2) difficult common bile duct stones; and (3) endoscopic sphincterotomy. Fifteen full papers were identified, comprising eleven retrospective studies, three controlled trials and one prospective case series[8-11,13-18,22-26].

| Ref. | Design | No. of cases | CBD stone diameter (mm) | Degree of EST | Balloon size (mm) | Complete stone removal overall, n (%) | Complete stone romoval initial, n (%) | No. sessions, mean | Application of ML, n (%) | PEP,n (%) | Bleeding,n (%) | Cholangitis, n (%) | Perforation, n (%) |

| Ersoz et al[8], 2003 | Retrospective | 58 | 16/18, mean | Moderate | 12-20, range | 58/58 (100) | 48/58 (82.8) | 1.2 | 4/58 (6.9) | 2/58 (3.4) | 3/58 (5.2) | 2/58 (3.4) | 0/58 (0) |

| Maydeo et al[9], 2007 | Prospective | 60 | 16, mean | Large | 12-15, mean | 60/60 (100) | 57/60 (95) | 1.0 | 3/60 (5) | 0/60 (0) | 1/60 (1.7) | 0/60 (0) | 0/60 (0) |

| Heo et al[10], 2007 | Randmized controlled trial | 100 | 16, mean | Moderate | 12-20, range | 97/100 (97) | 83/100 (83) | 1.1 | 8/100 (8) | 4/100 (4) | 0/100 (0) | 0/100 (0) | 0/100 (0) |

| Minami et al[11], 2007 | Retrospective | 88 | 14, mean | Small | 12-20, range | 87/88 (98.9) | 87/88 (98.9) | 1.0 | 1/88 (1.1) | 1/88 (1.1) | 1/88 (1.1) | 1/88 (1.1) | 0/88 (0) |

| Misra et al[13], 2008 | Retrospective | 50 | 15-25, range | Adequate | 12-20, range | NA | NA | NA | 5/50 (10) | 4/50 (8) | 2/50 (4) | 0/50 (0) | 0/50 (0) |

| Attasaranya et al[14], 2008 | Retrospective | 103 | 13, median | Discretion of endoscopist | 13.5, median | 102/107 (95.1) | 102/107 (95.1) | 1.0 | 28/103 (27.2) | 0/103 (0) | 2/103 (1.9) | 0/103 (0) | 1/103 (1) |

| Itoi et al[15], 2009 | Retrospective | 53 | 14.8, mean | Moderate | 12-20, range | 53/53 (100) | 51/53 (96.2) | 1 | 3/53 (5.7) | 1/53 (1.9) | 0/53 (0) | 1/53 (1.9) | 0/53 (0) |

| Jeong et al[16], 2009 | Retrospective | 38 | 17.7, mean | Not performed | 15-18, range | 37/38 (97.4) | 25/37 (65.8) | NA | 8/38 (21.1) | 1/38 (2.6) | 0/38 (0) | 0/38 (0) | 0/38 (0) |

| Draganov et al[17], 2009 | Retrospective | 44 | 12.7, mean | Large | 10-15, range | 42/44 (95) | 37/44 (84) | 1.1 | 2/44 (4.5) | 0/44 (0) | 2/44 (4.5) | 1/44 (2.2) | 0/44 (0) |

| Kim et al[18], 2009 | Randmized controlled trial | 27 | 20.8, mean | Small | 15-18, range | 27/27 (100) | 23/27 (85.2) | 1.3 | 9/27 (33.3) | 0/27 (0) | 0/27 (0) | 0/27 (0) | 0/27 (0) |

| Stefanidis et al[22], 2011 | Randmized controlled trial | 45 | 12-20, range | Large | 12-20, range | 44/45 (97.8) | 44/45 (97.8) | 1.0 | 0/45 (0) | 1/45 (2.2) | 1/45 (2.2) | 0/45 (0) | 0/45 (0) |

| Chan et al[23], 2011 | Retrospective | 247 | 16.4, mean | Not performed | 11-20, range | 229/247 (92.7) | 202/247 (81.8) | 1.2 | 39/247 (15.8) | 2/247 (0.8) | 6/247 (2.4) | 1/247 (0.4) | 0/247 (0) |

| Kim et al[24], 2011 | Retrospective | 72 | 17.5, mean | Small | 12-20, range | 70/72 (97.2) | 63/72 (87.5) | 1.1 | 6/72 (8.3) | 5/72 (6.9) | 1/72 (1.3) | 0/72 (0) | 0/72 (0) |

| Jang et al[25], 2013 | Retrospective | 40 | 10.5, median | Not performed | 10-17, range | 40/40 (100) | 37/40 (92.5) | 1.1 | 1/40 (2.5) | 2/40 (5.0) | 0/40 (0) | 0/40 (0) | 0/40 (0) |

| Kogure et al[26], 2014 | Retrospective | 28 | 14, mean | Not performed | 12-18, range | 27/28 (96) | 25/28 (89) | 1.1 | 3/28 (11) | 1/28 (4) | 0/28 (0) | 0/28 (0) | 1/28 (4) |

| Present study | Prospective | 41 | 13.4 mean | Not performed | 11-20, range | 40/41 (97.5) | 36/41 (87.8) | 1.2 | 5/41 (12.2) | 2/41 (4.9) | 0/41 (0) | 0/41 (0) | 1/41 (2.4) |

In the present study, the rates of complete stone removal in the initial session and overall were 87.8% and 97.5%, respectively. The mean number of sessions required for complete stone removal was 1.2, and the rate of ML application was 12.2%. Our endoscopic outcome was compared with those performed with preceding EST (small to large) in Table 5[8-11,13-15,17,18,22,24]. The rates of complete stone removal in the initial session and overall ranged from 83% to 99% and 95% to 100%, respectively, and the number of sessions required for complete stone removal and rate of ML application ranged from 1.1 to 1.3 and 0% to 27%, respectively. Thus, our endoscopic outcomes were equivalent to those in other studies. In the studies of balloon dilatation without preceding EST, including our study, the initial and overall complete stone removal rates ranged from 66% to 93% and 93% to 100%, respectively (Table 5)[16,23,25,26], and the number of sessions required for complete stone removal and the rate of ML application ranged from 1.1 to 1.2, and 2.5% to 21%, respectively. Thus, the efficacy data suggest that EPLBD without preceding EST was a satisfactory outcome.

PEP occurred in 4.9% of patients in our study. EPBD has been reported to be associated with more frequent and severe PEP than EST[28-30]. PEP is believed to occur as a reaction to the direct physical compression effect of the balloon on the papilla, the pancreatic duct orifice or the pancreatic parenchyma, and stone removal might induce peripapillary edema or spasm of the sphincter[21]. We hypothesized that the relatively low PEP rates seen in the present study may be because the balloon dilatation was minimized, thereby reducing the severity of the trauma to the papilla. In addition, we used a 15-18 mm balloon rather than a 12-15 mm one when the distal common bile duct was 15 mm, thereby reducing inflation time. Using a larger balloon provided adequate dilatation of the papilla, facilitating stone removal at the orifice. Sugiyama et al[31] reported that age < 60 years and bile duct diameter < 9 mm were independent risk factors for PEP, although we noted no such correspondence in the present study. Attasaranya et al[14] reported low rates of PEP because the pancreatic duct orifice was separated from the biliary orifice after EST and noted that balloon dilatation forces are directed away from the pancreatic duct. However, their evidence was insufficient to support the hypothesis[16]. While PEP occurrence has been found to range from 0% to 7% in cases with preceding EST[8-11,13-15,17,18,22,24], rates ranged from 0.8% to 5.0% in cases without preceding EST[16,23,25,26], including the present study (Table 5). Therefore, we suggest that the efficacy of EST could not be judged based on the rate of occurrence of PEP.

Bleeding occurred less frequently with EPBD than EST (EPBD 0% vs EST 2.0%, P = 0.001)[7]. While the rate of bleeding occurrence has been found to range from 0% to 5% in procedures performed after EST[8-11,13-15,17,18,22,24], rates ranged from 0% to 2% in procedures performed without EST[16,23,25,26], including the present study. Based on these findings, we question the propriety of EST in EPLBD.

Perforation is considered the most serious adverse events of EPLBD. Park et al[32] reported that stricture of the distal common bile duct was an independent factor predictive of perforation and that, if strong resistance was encountered during balloon inflation, additional pressure should not be applied. EPLBD has been reported to be safe in Billroth II patients[25,33]. Perforation is understood to be caused by looping of the scope, not by the tip of the endoscope itself[34]. When surgery was performed in one patient in the present study, a very small stone was found in the retroperitoneal region of the dorsal side of the ampulla. This case with Billroth II had no stricture, no resistance on balloon dilatation and the progress of the scope to the ampulla of Vater did not meet with any difficulties. Regarding the endoscopic procedure, balloon pressure was 3 atm, balloon size was 15-18 mm and the dilatation time was 125 s (from starting inflation to finishing deflation). Upon review of this case, we considered that the endoscopic procedure was not performed incorrectly, and subsequent surgical investigation confirmed that the very small stone was pressed into the duct wall during balloon dilatation, resulting in perforation. Therefore, it is important that we should confirm not only the configuration of the distal bile duct but also the presence of very small stones before EPLBD.

We collected the blood, and performed magnetic resonance cholaongiopancreatography and/or abdominal ultrasound to recognize common bile duct stone every three months during follow-up. During the median follow-up period of 487 d, no cases of recurrence were noted in our study. One patient died of aspiration pneumonia 156 d after complete stone removal.

We encountered cases where the balloon waist did not disappear during dilatation. Lee et al[12] reported a series of endoscopic lithotomies with 100% complete stone removal in spite of a balloon waist disappearance rate of only 69%. In the present study, we noted no significant differences in complete stone removal, number of sessions, rate of application of ML, or rate of PEP between cases with and without balloon waist disappearance. Given the relatively small number of cases involved in the present study, further studies in a larger number of patients are needed to validate these findings.

Lee et al[12] speculated that it was caused by scar change of the incised orifice; however, this speculation has not been verified.

The present study was subject to several limitations. Our sample size was small and from a single center, with no control cases. Endoscopic outcomes were analyzed retrospectively with respect to balloon waist disappearance. Regarding the degree of the waist disappearance, although we did not establish a definition, we observed a disappearance rate of more than 80% among the cases. In particular, further investigations are needed to verify the relationship between the presence or absence of balloon waist disappearance and outcome. Based on these findings, EST before sphincteroplasty may be unnecessary in EPLBD. Furthermore, a randomized controlled study is needed to evaluate any differences between prior EST and no prior EST.

Ersoz et al first reported on the utility of endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation (EPLBD) to remove large bile duct stones, and a number of subsequent studies further reported on the efficacy and safety of the procedure. However, opinions differ on whether or not to use an endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) incision and the degree of such an incision (small, moderate or large).

Jeong et al reported that EPLBD using a large size balloon (15-18 mm) without EST was both effective and safe. However, few studies have been conducted to verify the utility of this technique.

Balloon diameter selection was determined based on the previously described distal common bile duct diameter. For example, for 15-mm, a 15-18 mm balloon was selected to obtain a larger opening of the orifice, and inflation of the balloon to the desired pressure was performed until the desired pressure was achieved. When the balloon waist did not disappear and the desired pressure was satisfied, the dilatation was judged as complete. The presence or absence of waist disappearance with clinical characteristics and endoscopic outcome were compared.

Complete stone removal was achieved in 97.5% of patients (40/41); the mean number of sessions required for complete stone removal was 1.2 ± 0.62. The rate of application of mechanical lithotripter (ML) was 12.2% (5/41), and the rate of waist disappearance was 73.1% (30/41). Mild post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis occurred in two patients (4.9%). No significant differences were noted in procedure time, rate of complete stone removal, number of sessions, application of ML or occurrence of pancreatitis between cases with and without waist disappearance.

EST before sphincteroplasty may be unnecessary in EPLBD. A randomized controlled study is needed to evaluate any differences between prior EST and no prior EST. Further investigations are needed to verify the relationship between the presence or absence of balloon waist disappearance and outcome.

In this paper, the authors investigated the efficacy and safety of EPLBD without EST. The topic of this study is interesting.

P- Reviewer: Nakahara K, Sun LM, Tsuyuguchi T S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Stewart G E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Sand J, Airo I, Hiltunen KM, Mattila J, Nordback I. Changes in biliary bacteria after endoscopic cholangiography and sphincterotomy. Am Surg. 1992;58:324-328. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Kurumado K, Nagai T, Kondo Y, Abe H. Long-term observations on morphological changes of choledochal epithelium after choledochoenterostomy in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:809-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1689] [Article Influence: 58.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | May GR, Cotton PB, Edmunds SE, Chong W. Removal of stones from the bile duct at ERCP without sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:749-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mac Mathuna P, White P, Clarke E, Lennon J, Crowe J. Endoscopic sphincteroplasty: a novel and safe alternative to papillotomy in the management of bile duct stones. Gut. 1994;35:127-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mathuna PM, White P, Clarke E, Merriman R, Lennon JR, Crowe J. Endoscopic balloon sphincteroplasty (papillary dilation) for bile duct stones: efficacy, safety, and follow-up in 100 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:468-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Baron TH, Harewood GC. Endoscopic balloon dilation of the biliary sphincter compared to endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy for removal of common bile duct stones during ERCP: a metaanalysis of randomized, controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1455-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ersoz G, Tekesin O, Ozutemiz AO, Gunsar F. Biliary sphincterotomy plus dilation with a large balloon for bile duct stones that are difficult to extract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:156-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Maydeo A, Bhandari S. Balloon sphincteroplasty for removing difficult bile duct stones. Endoscopy. 2007;39:958-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Heo JH, Kang DH, Jung HJ, Kwon DS, An JK, Kim BS, Suh KD, Lee SY, Lee JH, Kim GH. Endoscopic sphincterotomy plus large-balloon dilation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of bile-duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:720-726; quiz 768, 771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Minami A, Hirose S, Nomoto T, Hayakawa S. Small sphincterotomy combined with papillary dilation with large balloon permits retrieval of large stones without mechanical lithotripsy. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2179-2182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee DK, Lee B, Hwhang S, Baik YH, Lee SJ. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation after endoscopic sphincterotomy for treatment of large common bile duct stones. Dig Endosc. 2007;19:S52-S56. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Misra SP, Dwivedi M. Large-diameter balloon dilation after endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of difficult bile duct stones. Endoscopy. 2008;40:209-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Attasaranya S, Cheon YK, Vittal H, Howell DA, Wakelin DE, Cunningham JT, Ajmere N, Ste Marie RW, Bhattacharya K, Gupta K. Large-diameter biliary orifice balloon dilation to aid in endoscopic bile duct stone removal: a multicenter series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:1046-1052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Itoi T, Itokawa F, Sofuni A, Kurihara T, Tsuchiya T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Ikeuchi N, Moriyasu F. Endoscopic sphincterotomy combined with large balloon dilation can reduce the procedure time and fluoroscopy time for removal of large bile duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:560-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Jeong S, Ki SH, Lee DH, Lee JI, Lee JW, Kwon KS, Kim HG, Shin YW, Kim YS. Endoscopic large-balloon sphincteroplasty without preceding sphincterotomy for the removal of large bile duct stones: a preliminary study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:915-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Draganov PV, Evans W, Fazel A, Forsmark CE. Large size balloon dilation of the ampulla after biliary sphincterotomy can facilitate endoscopic extraction of difficult bile duct stones. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:782-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kim HG, Cheon YK, Cho YD, Moon JH, Park do H, Lee TH, Choi HJ, Park SH, Lee JS, Lee MS. Small sphincterotomy combined with endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation versus sphincterotomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4298-4304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kurita A, Maguchi H, Takahashi K, Katanuma A, Osanai M. Large balloon dilation for the treatment of recurrent bile duct stones in patients with previous endoscopic sphincterotomy: preliminary results. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1242-1247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim HW, Kang DH, Choi CW, Park JH, Lee JH, Kim MD, Kim ID, Yoon KT, Cho M, Jeon UB. Limited endoscopic sphincterotomy plus large balloon dilation for choledocholithiasis with periampullary diverticula. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4335-4340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Youn YH, Lim HC, Jahng JH, Jang SI, You JH, Park JS, Lee SJ, Lee DK. The increase in balloon size to over 15 mm does not affect the development of pancreatitis after endoscopic papillary large balloon dilatation for bile duct stone removal. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1572-1577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Stefanidis G, Viazis N, Pleskow D, Manolakopoulos S, Theocharis L, Christodoulou C, Kotsikoros N, Giannousis J, Sgouros S, Rodias M. Large balloon dilation vs. mechanical lithotripsy for the management of large bile duct stones: a prospective randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:278-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chan HH, Lai KH, Lin CK, Tsai WL, Wang EM, Hsu PI, Chen WC, Yu HC, Wang HM, Tsay FW. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation alone without sphincterotomy for the treatment of large common bile duct stones. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kim TH, Oh HJ, Lee JY, Sohn YW. Can a small endoscopic sphincterotomy plus a large-balloon dilation reduce the use of mechanical lithotripsy in patients with large bile duct stones? Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3330-3337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jang HW, Lee KJ, Jung MJ, Jung JW, Park JY, Park SW, Song SY, Chung JB, Bang S. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilatation alone is safe and effective for the treatment of difficult choledocholithiasis in cases of Billroth II gastrectomy: a single center experience. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1737-1743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kogure H, Tsujino T, Isayama H, Takahara N, Uchino R, Hamada T, Miyabayashi K, Mizuno S, Mohri D, Yashima Y. Short- and long-term outcomes of endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation with or without sphincterotomy for removal of large bile duct stones. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:121-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Cotton PB, Eisen GM, Aabakken L, Baron TH, Hutter MM, Jacobson BC, Mergener K, Nemcek A, Petersen BT, Petrini JL. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:446-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1238] [Cited by in RCA: 1841] [Article Influence: 122.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Bergman JJ, Rauws EA, Fockens P, van Berkel AM, Bossuyt PM, Tijssen JG, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Randomised trial of endoscopic balloon dilation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of bileduct stones. Lancet. 1997;349:1124-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Vlavianos P, Chopra K, Mandalia S, Anderson M, Thompson J, Westaby D. Endoscopic balloon dilatation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy for the removal of bile duct stones: a prospective randomised trial. Gut. 2003;52:1165-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Disario JA, Freeman ML, Bjorkman DJ, Macmathuna P, Petersen BT, Jaffe PE, Morales TG, Hixson LJ, Sherman S, Lehman GA. Endoscopic balloon dilation compared with sphincterotomy for extraction of bile duct stones. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1291-1299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sugiyama M, Izumisato Y, Abe N, Masaki T, Mori T, Atomi Y. Predictive factors for acute pancreatitis and hyperamylasemia after endoscopic papillary balloon dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:531-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Park SJ, Kim JH, Hwang JC, Kim HG, Lee DH, Jeong S, Cha SW, Cho YD, Kim HJ, Kim JH. Factors predictive of adverse events following endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation: results from a multicenter series. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1100-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Choi CW, Choi JS, Kang DH, Kim BG, Kim HW, Park SB, Yoon KT, Cho M. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation in Billroth II gastrectomy patients with bile duct stones. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:256-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ciçek B, Parlak E, Dişibeyaz S, Koksal AS, Sahin B. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with Billroth II gastroenterostomy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1210-1213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |