Published online Jun 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i22.6944

Peer-review started: January 9, 2015

First decision: January 22, 2015

Revised: February 27, 2015

Accepted: April 3, 2015

Article in press: April 3, 2015

Published online: June 14, 2015

Processing time: 160 Days and 17.2 Hours

AIM: To investigate celiac artery variations in gastric cancer patients and the impact on gastric cancer surgery, and also to discuss the value of the ultrasonic knife in reducing the risk caused by celiac artery variations.

METHODS: A retrospective analysis was conducted to investigate the difference in average operation time, intraoperative blood loss, number of harvested lymph nodes, average postoperative drainage within 3 d, and postoperative hospital stay between the group with vascular variations and no vascular variations, and between the ultrasonic harmonic scalpel and conventional electric scalpel surgery group.

RESULTS: One hundred and fifty-eight cases presented with normal celiac artery, and 80 presented with celiac artery variation (33.61%). The average operation time, blood loss, average drainage within 3 d after surgery in the celiac artery variation group were significantly more than in the no celiac artery variation group (215.7 ± 32.7 min vs 204.2 ± 31.3 min, 220.0 ± 56.7 mL vs 163.1 ± 52.3 mL, 193.6 ± 41.4 mL vs 175.3 ± 34.1 mL, respectively, P < 0.05). In celiac artery variation patients, the average operation time, blood loss, average drainage within 3 d after surgery in the ultrasonic harmonic scalpel group were significantly lower than in the conventional electric scalpel surgery group (209.5 ± 34.9 min vs 226.9 ± 29.4 min, 207.5 ± 57.1 mL vs 235.6 ± 52.9 mL, 184.4 ± 38.2 mL vs 205.0 ± 42.9 mL, respectively, P < 0.05), and the number of lymph node dissections was significantly higher than in the conventional surgery group (25.5 ± 9.2 vs 19.9 ± 7.8, P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: Celiac artery variation increases the difficulty and risk of radical gastrectomy. Preoperative imaging evaluation and the application of ultrasonic harmonic scalpel are conducive to radical gastrectomy.

Core tip: Celiac artery variation is quite common in gastric cancer patients, and may obviously increase the difficulty and risk of radical gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy. With the development of imaging techniques, not only the accuracy of preoperative staging, but also the individualized image information about celiac artery variation will be improved. Meanwhile, the application of new technology such as ultrasonic harmonic scalpel is conducive to radical gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy and could reduce the risk caused by celiac artery variation; therefore, its utilization is to be recommended.

- Citation: Huang Y, Mu GC, Qin XG, Chen ZB, Lin JL, Zeng YJ. Study of celiac artery variations and related surgical techniques in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(22): 6944-6951

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i22/6944.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i22.6944

Gastric cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors in China. Its position has increased to third most common from the previous number four, and is preceded only by lung cancer and breast cancer. In 2010 alone, 404565 cases with new onset of gastric cancer were reported, and 287851 patients died from gastric cancer. The mortality is number three among various malignant cancers[1-3]. At present, surgery remains the main treatment for gastric cancer, wherein D2 radical gastrectomy has already become the standard operation for gastric cancer at the progression stage. Focus and difficulty of D2 radical gastrectomy are dissection of lymph nodes around vessels such as celiac trunk, left gastric artery and hepatic artery. As reported in the literature, a high rate of celiac artery variation has been found in liver transplantation, especially in the hepatic arterial system; the rate of variation is up to 24.3%[4,5]. Presence of celiac artery variation will definitely increase surgical difficulty and risk. In addition, relevant studies on celiac artery variation among gastric cancer patients are still lacking. Meanwhile, gastric cancer treatment guidelines do not state how to handle an abnormal vessel and its surrounding lymph nodes. This study aims at analyzing retrospectively celiac artery variation and the effect of vascular variation on gastric cancer surgery outcome among 238 patients receiving radical gastrectomy, meanwhile addressing the efficacy of ultrasound harmonic scalpel in minimizing risk due to vascular variation, so as to provide a reference for guiding gastric cancer treatment in clinical practice.

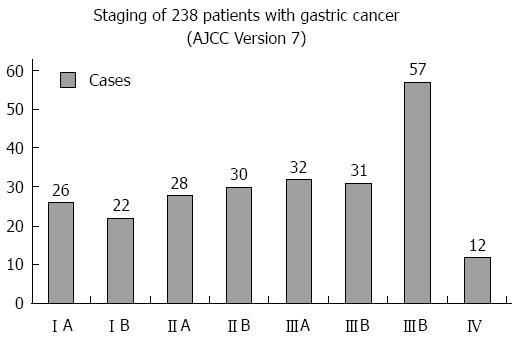

Two hundred and thirty-eight patients undergoing D2 radical gastrectomy by well experienced general surgeons in our department from January 2009 to May 2014 were included; the detailed information of tumor staging can be seen in Figure 1. All patients provided informed consent, and signed agreements. All the patients were preoperatively examined, through upper abdominal 64 multi-slice computed tomography angiography (MSCTA), to determine whether there was variation in the celiac trunk and its branches, wherein the abnormal hepatic artery was classified with reference to Hiatt’s[4] classification.

Inclusion criteria: (1) preoperative pathology via gastroscopic biopsy indicated gastric cancer; (2) preoperative MSCTA was taken; (3) preoperative assessment showed indications for D2 radical surgery; (4) preoperative assessment showed no evident surgical contraindication; and (5) D2 or D2+ radical surgery was performed.

Exclusion criteria: (1) no MSCTA was taken preoperatively; (2) preoperative imaging examination indicated distant metastasis or infiltration into surrounding tissue and organ, which was confirmed by laparoscopy; (3) preoperative assessment showed severe diseases of cardiopulmonary and other systems, and the patient might not be able to tolerate the operation; and (4) intraoperative exploration found extensive metastasis, malignant ascites, infiltration into surrounding tissue in the abdominal cavity, so that neither D2 or D2+radical surgery was practical.

D2 surgery for gastric cancer was undertaken according to Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines (Ver. 3)[6]. TNM staging was in accordance with the 7th AJCC classification criteria. Indices including average operation time, intraoperative blood loss, total number of lymph nodes dissected, time required for postoperative recovery of bowel function, time to ambulation after surgery, postoperative hospital stay, mean drainage amount at 3 d after operation, as well as presence of postoperative complications such as bleeding, anastomosis fistula, lymphatic fistula, postoperative pancreatitis, incision infection, postoperative pneumonia, etc., were recorded for the vascular variation group and no vascular variation group, as well as ultrasonic harmonic scalpel surgery subgroup and conventional electric scalpel surgery subgroup in the vascular variation group. Indices were analyzed via comparison between the two groups described above, to evaluate the influence of vascular variation on operative safety and postoperative recovery, as well as to explore the effect of the ultrasonic harmonic scalpel in terms of decreasing risk due to abnormal vessels.

Statistical analysis was carried out with statistical software SPSS16.0. χ2 test was used to compare general data construction between two groups, and t-test was used to analyze differences in various statistical parameters between the vascular variation group and no vascular variation group, as well as ultrasonic harmonic scalpel surgery subgroup and conventional electric scalpel subgroup in the vascular variation group. P < 0.05 was considered to be a statistically significant difference. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Huang Gao-Ming from the College of Public Hygiene of Guangxi Medical University.

This study showed that there were 158 cases with normal celiac artery and 80 cases with celiac artery variation, with a variation rate of 33.61%. Among them, 68 cases had abnormal hepatic artery, and were classified and compared according to Hiatt’ classification criteria (Table 1).

| Hiatt’s classification | In Hiatt’s study | In this study | χ2value | P value |

| I | 757 (75.70) | 170 (71.43) | 1.865 | 0.172 |

| II | 97 (9.70) | 33 (13.87) | 3.549 | 0.060 |

| III | 106 (10.60) | 14 (5.88) | 4.888 | 0.027 |

| IV | 23 (2.30) | 7 (2.94) | 0.334 | 0.563 |

| V | 15 (1.50) | 6 (2.52) | 0.668 | 0.414 |

| VI | 2 (0.20) | 0 (0.00) | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Others | 0 (0.00) | 8 (3.36) | 27.831 | 0.000 |

| In total | 1000 (100.00) | 238 (100.00) |

Five cases had abnormal left gastric artery: two cases had left gastric artery deriving from the abdominal aorta, one case deriving from splenic artery, one case with left gastric artery absence, and one case with two left gastric arteries deriving from the celiac trunk, specifically sharing the same trunk from 4 mm and subsequently branching into two left gastric arteries.

Additionally, two cases had abnormal splenic arteries deriving from superior mesenteric artery; two cases had celiac trunks which shared the same trunk with the superior mesenteric artery and derived from the abdominal aorta; two cases had gastroduodenal arteries deriving from the celiac trunk; and one case had right gastric artery deriving from the gastroduodenal artery.

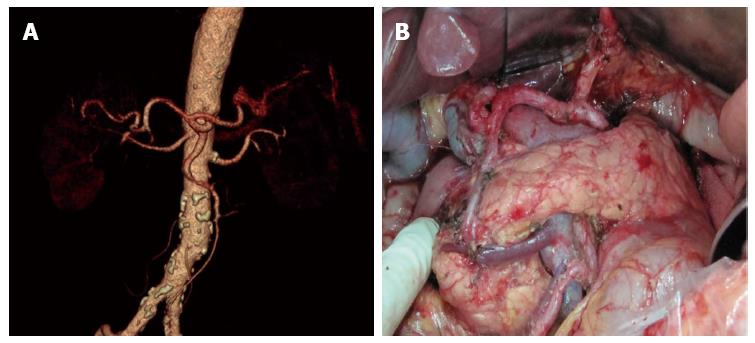

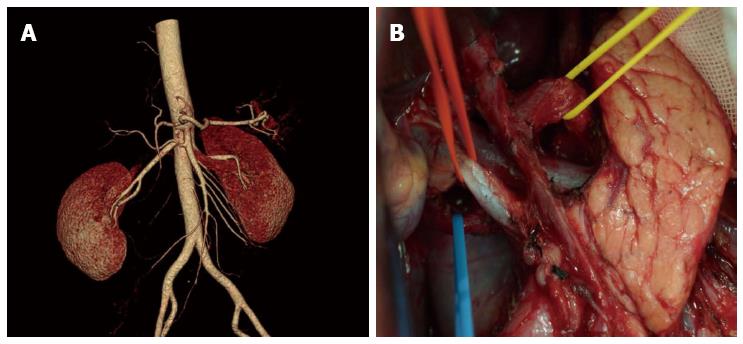

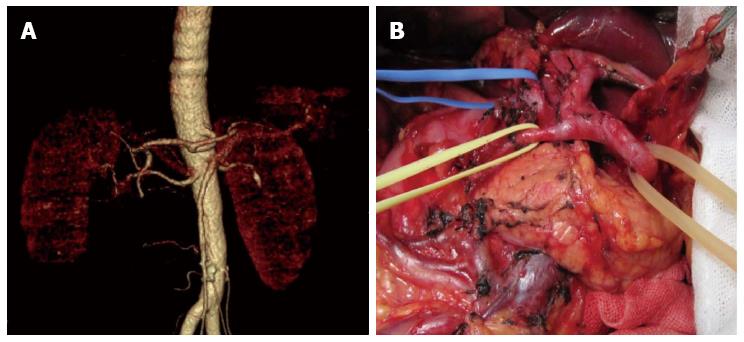

There were significant differences between the 80 patients with vascular variation and 158 patients with no vascular variation in distribution of general data. All the patients received uneventful surgery, without occurrence of severe intraoperative or postoperative complications. There were 12 cases with postoperative complications, including incision infection and postoperative pneumonia. No postoperative anastomosis fistula or anastomotic bleeding occurred (Table 2). Comparing results of the study showed that celiac artery variation prolonged operation duration significantly and increased intraoperative bleeding and postoperative drainage amount, but the total number of lymph nodes dissected, time required for postoperative recovery of bowel function, time to ambulation after surgery, postoperative hospital stay, and total hospitalization costs were not significantly different (Table 3). Among patients with celiac artery variation, operation duration, intraoperative blood loss, and postoperative amount of drainage in the ultrasonic harmonic scalpel group were significantly decreased compared to the conventional electric scalpel surgery group, and total number of lymph nodes dissected was increased, whereas time required for postoperative recovery of bowel function, time to ambulation after surgery, postoperative hospital stay, and total hospitalization cost were not significantly different (Table 4). The relative results can be seen in the comparison of observations between the ultrasonic harmonic scalpel subgroup and the electrical unit subgroup among the no vascular variation population in Table 5. Images of the preoperative MSCTA examination and lymph node dissection by ultrasonic harmonic scalpel can be seen in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4.

| Clinical data | Vascular variation group | No vascular variation group | Statistics value | P value |

| Total cases | 80 | 158 | ||

| Age (yr) | 58.3 + 12.5 | 56.3 + 12.4 | 1.195 | 0.233 |

| Sex | 0.633 | 0.426 | ||

| Male | 61 | 112 | ||

| Female | 19 | 46 | ||

| Tumor location | 0.115 | 0.944 | ||

| Fundus ventriculi | 17 | 33 | ||

| Corpus ventriculi | 13 | 24 | ||

| Gastric antrum | 50 | 101 | ||

| Gastric cancer staging | 1.343 | 0.246 | ||

| Stage I-II | 31 | 75 | ||

| Stage III-IV | 49 | 83 | ||

| Postoperative complications | 0.086 | 0.770 | ||

| Yes | 5 | 7 | ||

| No | 75 | 151 | ||

| Observations index | Vascular variation group | No vascular variation group | t value | P value |

| Operation time (min) | 215.7 ± 32.7 | 204.2 ± 31.3 | 2.624 | 0.009 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 220.0 ± 56.7 | 163.1 ± 52.3 | 7.674 | 0.000 |

| Total number of lymph nodes dissected | 23.0 ± 9.1 | 21.2 ± 8.5 | 1.505 | 0.134 |

| Time required for postoperative recovery of bowel function (d) | 3.0 ± 1.2 | 3.2 ± 1.4 | 1.260 | 0.209 |

| Time to ambulation (d) | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 4.1 ± 1.0 | 2.760 | 0.060 |

| Postoperative hospitalization (d) | 7.6 ± 1.2 | 8.1 ± 0.9 | 1.356 | 0.121 |

| Mean drainage amount in 3 d after operation (mL) | 193.6 ± 41.4 | 175.3 ± 34.1 | 1.639 | 0.032 |

| Total hospitalization cost (RMB) | 35862.8 ± 2965.3 | 36759.3 ± 2732.5 | 1.356 | 0.130 |

| Observation | Ultrasonic harmonic scalpel group | Electrical unit subgroup | t value | P value |

| Cases (persons) | 44 | 36 | ||

| Operation duration (min) | 209.5 ± 34.9 | 226.9 ± 29.4 | 1.168 | 0.046 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 207.5 ± 57.1 | 235.6 ± 52.9 | 2.242 | 0.028 |

| Total number of lymph nodes dissected | 25.5 ± 9.2 | 19.9 ± 7.8 | 2.903 | 0.005 |

| Time required for postoperative recovery of bowel function (d) | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 0.442 | 0.660 |

| Time to ambulation (d) | 4.0 ± 0.9 | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 0.291 | 0.772 |

| Postoperative hospitalization (d) | 7.4 ± 1.3 | 8.1 ± 1.1 | 1.251 | 0.101 |

| Mean drainage amount in 3 d after operation (mL) | 184.4 ± 38.2 | 205.0 ± 42.9 | 2.255 | 0.027 |

| Total hospitalization cost (RMB) | 36167.3 ± 2845.6 | 35246.4 ± 2789.5 | 1.236 | 0.102 |

| Observation | Ultrasonic harmonic scalpel group | Electrical unit subgroup | t value | P value |

| Cases (persons) | 81 | 77 | ||

| Operation duration (min) | 188.4 ± 25.4 | 220.4 ± 28.3 | 7.481 | 0.000 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 168.1 ± 49.6 | 158.0 ± 55.3 | 1.210 | 0.228 |

| Total number of lymph nodes dissected | 23.3 ± 7.9 | 19.2 ± 8.6 | 3.085 | 0.002 |

| Time required for postoperative recovery of bowel function (d) | 3.3 ± 1.1 | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 1.359 | 0.176 |

| Time to ambulation (d) | 4.4 ± 1.0 | 4.2 ± 1.0 | 1.330 | 0.185 |

| Postoperative hospitalization (d) | 7.3 ± 1.5 | 7.9 ± 1.2 | 1.251 | 0.132 |

| Mean drainage amount in 3 d after operation (mL) | 191.3 ± 37.0 | 187.7 ± 30.0 | 2.349 | 0.080 |

| Total hospitalization cost (RMB) | 35917.6 ± 2741.6 | 36186.9 ± 2717.3 | 1.016 | 0.161 |

Gastric cancer is the third most common and the malignant tumor with the second highest mortality in Asia[7]. The incidence of gastric cancer has an increasing trend in China. It possesses a great threat to the mental and physical health of people, and is an important public health issue in China, as well as exerting a heavy economic burden on the Chinese healthcare community[8,9]. At present, radical gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy is widely accepted by an increasing number of surgeons as a standard of surgery for advanced gastric cancer[10]. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines (Ver. 3) also specifies D2 lymphadenectomy as the standard operation[6]. Focus and difficulty of D2 radical surgery is to skeletonize vessels at the left gastric artery, celiac trunk, hepatic artery and hepatoduodenal ligament, and to dissect the corresponding group of lymph nodes. Any branch of the celiac artery could be a variation, which definitely will increase the difficulty and risk of operation. Therefore, preoperative imaging assessment of the presence of celiac artery variation and route of the normal branch gives importance guidance for the operation. Meanwhile, gastric cancer treatment guidelines do not state whether lymph nodes around an abnormal vessel should be dissected. Therefore, study of celiac artery variation among gastric cancer patients has important clinical implications for guiding gastric cancer surgical strategy development.

The celiac artery has a high variation rate. Our data showed the variation rate is up to 33.61%, wherein, hepatic artery variation is the most common with a rate of 28.57%, which is slightly higher than 20.4% reported in the literature[11]. This may be attributed to the fact that the previous studies mainly focused on intraoperative anatomic findings during hepatic implantation, and were subject to ignore small vascular anomalies. The majority were replaced/accessory left hepatic artery, with an incidence of 16.8%, which is similar to that reported in literature[12-15]. Replaced/accessory left hepatic artery has important implications in D2 radical gastrectomy. It is necessary during surgery to ligate at the root and cut off the left gastric artery, which may affect the hepatic tissue supplied by the replaced/accessory left hepatic artery deriving from the left gastric artery, thus influencing hepatic function, especially for the replaced right hepatic artery[16-18]. A study believed that intraoperative resection of the accessory right hepatic artery was safe for patients without chronic hepatic disease; however, for patients complicated with chronic hepatic disease, it had to be reserved for protecting hepatic function[19]. Therefore, accurate preoperative assessment of whether the abnormal left hepatic artery is replaced by the right hepatic artery or accessory right hepatic artery is especially important. Oki et al[20] believed that preoperative 3DCT and angiography could not differentiate replaced and accessory hepatic artery; therefore, they recommended that all abnormal left hepatic arteries should be preserved intraoperatively. Based on data from this study, results have shown that continuous tracking of vessels flowing into the liver via preoperative CTA in combination with thin layer scanning at arterial phase could well differentiate these two. For lymph nodes around normal hepatic arteries deriving from the superior mesenteric artery, results from our previous study indicated no necessity for dissection; however, due to limitations regarding the small sample size, no definite conclusion could be drawn, and studies with larger sample size and prospective comparative studies of influence on outcome are still awaited[21].

In D2 radical gastrectomy, skeletonizing should be performed for vessels around the stomach to dissect corresponding groups of lymph nodes. Vascular variation around the stomach increases difficulty and risk of lymph node dissection[22,23]. Our data showed the operation time in the vascular variation group was increased as compared to the no variation group (215.7 min vs 204.2 min). To avoid damaging abnormal vessels and causing unnecessary accessory injury, we should perform more precise dissection for anomalous vessels. In the meantime, for patients at an advanced age and with scleratheroma, we recommend to perform lymph node dissection outside the vascular sheath, to avoid damaging vessels, inducing aneurysm and risking rupture and bleeding. Intraoperative accidental injury of abnormal hepatic artery will influence hepatic function directly[24]. Furthermore, prolonged operation duration may also be an important factor of hepatic impairment. A comparative study of laparoscopic radical gastrectomy and conventional laparotomy by Jeong et al[25] showed the operation time, BMI index, intraoperative hepatic injury and mistakenly pricking the hepatic artery are important factors influencing postoperative hepatic function. Meanwhile, celiac artery variation could significantly increase intraoperative blood loss, especially in those who lacked effective preoperative assessment of the abdominal artery. Perioperative bleeding could be decreased through preoperative CTA assessment of celiac artery imaging information[26].

Results of this study showed that the celiac artery variation significantly extended operation time and increased intraoperative blood loss and postoperative amount of drainage, and therefore was an important factor influencing successful implementation of D2 radical gastrectomy and postoperative recovery. Recently, innovative devices such as the ultrasonic harmonic scalpel have been introduced to clinical practice, and their scope of use has been extended gradually. With their increasing surgical speed and quality, they thus add new elements to gastric cancer surgery[27-29]. Prospective, randomized controlled study on the ultrasonic harmonic scalpel and conventional electric scalpel showed that the ultrasonic harmonic scalpel could significantly reduce radical gastrectomy operation time and perioperative bleeding (209.5 min vs 226.9 min, 207.5 mL vs 235.6 mL, respectively), and had an evident advantage in terms of lymph node dissection[29]. The value of the ultrasonic harmonic scalpel during operation among gastric cancer patients with celiac artery variation is worthy of further exploration. This study showed that the ultrasonic harmonic scalpel had an evident advantage during celiac artery variation surgery, as it effectively reduced operation duration and intraoperative blood loss. Ultrasonic harmonic scalpel could coagulate vessels with a diameter up to 5 mm, and greatly decrease additional vascular ligation during transection of the greater omentum, splenogastric ligament and hepatogastric ligament, so as to make the surgery smoother and significantly reduce operation time and perioperative bleeding. Especially during dissection of lymph nodes around an abnormal hepatic artery deriving from the superior mesenteric artery and reserving abnormal left hepatic artery deriving from the left gastric artery, the operation could be achieved along the vascular surface with the thinner tip of an ultrasonic harmonic scalpel, facilitating vascular skeletonizing, so as to not only achieve more complete lymph node dissection, but also to find the root of the abnormal vessel easily. Thus accessory injury and additional bleeding due to damaging the abnormal hepatic artery could be avoided. Meanwhile, the ultrasonic harmonic scalpel could close arteries and veins, capillaries and lymph vessels in the wound bed, and intraoperative bleeding and postoperative amount of abdominal drainage is significantly decreased.

In conclusion, celiac artery variation is common in clinical practice, and therefore great attention should be paid to it. Vascular variation increases difficulty and risk of radical gastrectomy. Application of new techniques such as preoperative imaging assessment and the ultrasonic harmonic scalpel could facilitate successful implementation of D2 radical gastrectomy and efficiently decrease risk due to celiac artery variation, meanwhile hospitalization days and cost are not increased significantly. Therefore, they are recommended to be applied widely. However, this study could not arrive at definite conclusions since it was limited as a retrospective study; a larger number of cases in larger studies need to be examined and randomized controlled trial studies need to be carried out.

Gastric cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors in China. At present, surgery remains the main treatment for gastric cancer, wherein D2 radical gastrectomy has already become the standard operation for gastric cancer at the progression stage. Focus and difficulty of D2 radical gastrectomy are dissection of lymph nodes around vessels such as the celiac trunk, left gastric artery and hepatic artery. As reported in the literature, a high rate of celiac artery variation was found in liver transplantation, especially in the hepatic arterial system. The presence of celiac artery variation will definitely increase surgical difficulty and risk. In addition, relevant studies on celiac artery variation among gastric cancer patients are still lacking. Meanwhile, gastric cancer treatment guidelines do not state how to handle an abnormal vessel and its surrounding lymph nodes. This study aims at analyzing retrospectively celiac artery variation and effects of vascular variation on gastric cancer surgery among 238 patients receiving radical gastrectomy, meanwhile addressing efficacy of ultrasound harmonic scalpel regarding risk due to vascular variation, so as to provide a reference for guiding gastric cancer treatment in clinical practice.

Although D2 radical gastrectomy has already become the standard surgery for gastric cancer at the progression stage in the east and west, vascular variation around the stomach has been the focus and difficulty of gastric cancer surgery, and gastric cancer treatment guidelines do not state how to handle an abnormal vessel and its surrounding lymph nodes; lymph node metastasis around abnormal vascular will be one of hotspots in the future.

The main innovation of this study was that it mainly investigated celiac artery variation among gastric cancer patients and also discussed the values of ultrasonic knife in reducing the risk caused by celiac artery variations. Celiac artery variation increases the difficulty and risk of radical gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy. Preoperative imaging evaluation and the application of new technology such as ultrasonic harmonic scalpel are conducive to radical gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy and could reduce the risk caused by celiac artery variation, and are therefore applications worthy of promotion.

Celiac artery variation is common in gastric cancer patients. The authors should pay attention to celiac artery variations and undertake preoperative imaging evaluation because celiac artery variations may increase the difficulty and risk of radical gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy. However, the ultrasonic harmonic scalpel could reduce the risk caused by celiac artery variation.

This is a prospective and controlled clinical study that emphasizes one of the important clinical problems surgeons face. It is important to show the prevalence of Celiac Artery Variations and to test whether the ultrasonic knife is a better tool than conventional methods. Both aspects of the study have clinical applicability.

P- Reviewer: Altun A S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Logan S E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Chen W, Zheng R, Zhang S, Zhao P, Zeng H, Zou X, He J. Annual report on status of cancer in China, 2010. Chin J Cancer Res. 2014;26:48-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jing JJ, Liu HY, Hao JK, Wang LN, Wang YP, Sun LH, Yuan Y. Gastric cancer incidence and mortality in Zhuanghe, China, between 2005 and 2010. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1262-1269. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Yan S, Li B, Bai ZZ, Wu JQ, Xie DW, Ma YC, Ma XX, Zhao JH, Guo XJ. Clinical epidemiology of gastric cancer in Hehuang valley of China: a 10-year epidemiological study of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10486-10494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hiatt JR, Gabbay J, Busuttil RW. Surgical anatomy of the hepatic arteries in 1000 cases. Ann Surg. 1994;220:50-52. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Kobayashi S, Otsubo T, Koizumi S, Ariizumi S, Katagiri S, Watanabe T, Nakano H, Yamamoto M. Anatomic variations of hepatic artery and new clinical classification based on abdominal angiographic images of 1200 cases. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:2345-2348. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1723] [Cited by in RCA: 1897] [Article Influence: 135.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rahman R, Asombang AW, Ibdah JA. Characteristics of gastric cancer in Asia. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4483-4490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yang L. Incidence and mortality of gastric cancer in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:17-20. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Fock KM, Ang TL. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer in Asia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:479-486. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Mu GC, Huang Y, Liu ZM, Lin JL, Zhang LL, Zeng YJ. Clinical research in individual information of celiac artery CT imaging and gastric cancer surgery. Clin Transl Oncol. 2013;15:774-779. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Yang Y, Jiang N, Lu MQ, Xu C, Cai CJ, Li H, Yi SH, Wang GS, Zhang J, Zhang JF. [Anatomical variation of the donor hepatic arteries: analysis of 843 cases]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2007;27:1164-1166. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Matsuki M, Kani H, Tatsugami F, Yoshikawa S, Narabayashi I, Lee SW, Shinohara H, Nomura E, Tanigawa N. Preoperative assessment of vascular anatomy around the stomach by 3D imaging using MDCT before laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:145-151. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Nakamura H, Uchida H, Kuroda C, Yoshioka H, Tokunaga K, Kitatani T, Sato T, Ohi H, Hori S. Accessory left gastric artery arising from left hepatic artery: angiographic study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1980;134:529-532. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Celik A, Celik AS, Altinli E, Beykal O, Caglayan K, Koksal N. Left gastric and right hepatic artery anomalies in a patient with gastric cancer: images for surgeons. Am J Surg. 2011;202:e13-e16. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Abid B, Douard R, Chevallier JM, Delmas V. [Left hepatic artery: anatomical variations and clinical implications]. Morphologie. 2008;92:154-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shinohara T, Ohyama S, Muto T, Yanaga K, Yamaguchi T. The significance of the aberrant left hepatic artery arising from the left gastric artery at curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:967-971. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Friesen SR. The significance of the anomalous origin of the left hepatic artery from the left gastric artery in operations upon the stomach and esophagus. Am Surg. 1957;23:1103-1108. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Lurie AS. The significance of the variant left accessory hepatic artery in surgery for proximal gastric cancer. Arch Surg. 1987;122:725-728. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Huang CM, Chen QY, Lin JX, Zheng CH, Li P, Xie JW, Wang JB, Lu J. Short-term clinical implications of the accessory left hepatic artery in patients undergoing radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Oki E, Sakaguchi Y, Hiroshige S, Kusumoto T, Kakeji Y, Maehara Y. Preservation of an aberrant hepatic artery arising from the left gastric artery during laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:e25-e27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Huang Y, Liu C, Lin JL, Mu GC, Zeng Y. Is it necessary to dissect the lymph nodes around an abnormal hepatic artery in D2 lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer? Clin Transl Oncol. 2013;15:472-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Huang Y, Liu C, Lin JL. Clinical significance of hepatic artery variations originating from the superior mesenteric artery in abdominal tumor surgery. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013;126:899-902. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Gielecki J, Zurada A, Sonpal N, Jabłońska B. The clinical relevance of coeliac trunk variations. Folia Morphol (Warsz). 2005;64:123-129. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Nakanishi R, Endo K, Yoshinaga K, Saeki H, Morita M, Kakeji Y, Maehara Y. Unique variation of the hepatic artery identified on preoperative three-dimensional computed tomography angiography in surgery for gastric cancer: report of a case. Surg Today. 2010;40:967-971. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Jeong GA, Cho GS, Shin EJ, Lee MS, Kim HC, Song OP. Liver function alterations after laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for gastric cancer and its clinical significance. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:372-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Miyaki A, Imamura K, Kobayashi R, Takami M, Matsumoto J, Takada Y. Preoperative assessment of perigastric vascular anatomy by multidetector computed tomography angiogram for laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2012;397:945-950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Massarweh NN, Cosgriff N, Slakey DP. Electrosurgery: history, principles, and current and future uses. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:520-530. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Sun ZC, Xu WG, Xiao XM, Yu WH, Xu DM, Xu HM, Gao HL, Wang RX. Ultrasonic dissection versus conventional electrocautery during gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:527-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Inoue K, Nakane Y, Michiura T, Yamada M, Mukaide H, Fukui J, Miki H, Ueyama Y, Nakatake R, Tokuhara K. Ultrasonic scalpel for gastric cancer surgery: a prospective randomized study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1840-1846. [PubMed] |