Published online Mar 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i11.3376

Peer-review started: July 26, 2014

First decision: October 14, 2014

Revised: October 25, 2014

Accepted: December 1, 2014

Article in press: December 1, 2014

Published online: March 21, 2015

Five-amino salicylic acids are recommended for use in the management of inflammatory bowel disease, cardiac complications are a rare although recognised phenomenon. This report aims to highlight this serious but rare adverse reaction. We report here a case of a young man presenting with cardiogenic shock in the context of recent mesalazine treatment in severe ulcerative colitis.

Core tip: A rare but serious occurrence in ulcerative colitis is myocarditis which can often be life-threatening. Whether 5-amino salicylic acids induced (as proposed here), or an autoimmune phenomenon in acute disease flare-ups, prompt recognition and treatment will be of benefit in the clinical setting.

- Citation: Fleming K, Ashcroft A, Alexakis C, Tzias D, Groves C, Poullis A. Proposed case of mesalazine-induced cardiomyopathy in severe ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(11): 3376-3379

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i11/3376.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i11.3376

Five-amino salicylic acids (5-ASA) are recommended for use in the management of inflammatory bowel disease and are commonly prescribed by both gastroenterologists and general physicians[1]. Serious reactions are rare, but recognised side effects include pancreatitis, interstitial nephritis, blood dyscrasias and Stevens Johnson syndrome. Cardiac side effects from 5-ASA agents are extremely uncommon.

A previously fit and well, non-smoking 31 year old male, presented with a 6 wk history of progressive diarrhoea, rectal bleeding and abdominal pain. Flexible sigmoidoscopy revealed severe confluent inflammation from the rectum to the point of insertion in the mid-sigmoid. Microscopy and stool culture were negative. Colonic biopsies showed moderate active chronic colitis, consistent with the endoscopic suspicion of ulcerative colitis, and so he was started on high dose oral mesalazine (2.4 g twice daily) with a view to a prompt outpatient follow up within the next few days.

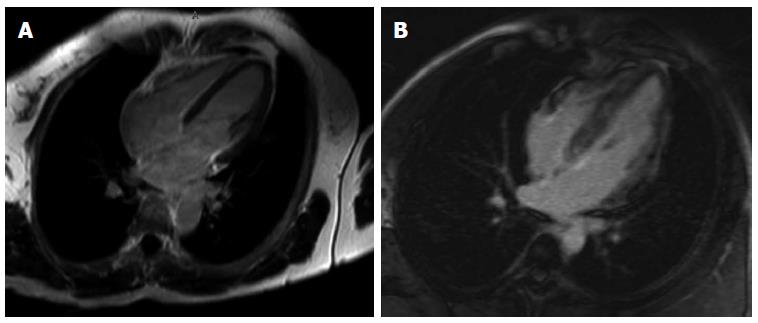

Three days later he presented to the emergency department with chest pain, raised inflammatory markers and an elevated troponin. Initial ECG showed ST depression and biphasic T waves in leads V4-5 with no reciprocal changes. Mesalazine therapy was stopped at this stage. His condition deteriorated with cardiogenic shock developing, which required increasing inotropic support and subsequent insertion of an intra-aortic balloon pump. Coronary angiography was normal. Subsequent cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed concentric hypertrophy and mildly impaired ejection fraction but no pericardial abnormalities. STIR2 imaging was suggestive of an acute inflammatory cardiac process. Gadolinium contrast studies excluded thrombi but showed diffuse heterogeneous enhancement of the myocardium suggestive of an atypical myocarditis, although other infiltrative cardiac pathologies (including sarcoid) were postulated (Figure 1). Serum virology showed no acute viral illness (previous parvovirus and previous Epstein-Barr virus positive but negative human immunodeficiency virus, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, influenza viruses A and B, coxsackie, CMV, adenovirus and enterovirus). An abdomen ultrasound scan was also unremarkable.

A diagnosis of myocarditis was highly suspected on clinical grounds and on day 2 of admission he underwent a cardiac biopsy. This showed several capillaries distended with microthrombi, myocyte vacuolation, interstitial oedema and focal haemorrhage. There was no evidence of vasculitis, fibrosis or amyloidosis. Similarly, there was no evidence of acute inflammatory infiltrate. On day 3 he suffered a cerebrovascular event manifest as acute right hemiplegia, right facial droop and dysarthria and he was treated with a heparin infusion. CT and subsequent MRI showed several acute and deep white matter infarcts highly suggestive of a cardiac source and bubble echo showed no evidence of intracardiac shunting.

Day 6 of admission he was weaned from inotropic and mechanical support. He was stepped-down from level 3 care. By day 10 repeat echo revealed significant improvement of left ventricular function and normal dimensions.

Throughout this period his ulcerative colitis progressed. Due to persistent bloody stool and resulting transfusion requirement his heparin infusion was discontinued and he was started on parenteral steroid therapy. Despite this, his clinical and biochemical parameters did not improve and he was commenced on a ciclosporin infusion as a bridging agent to long term azathioprine therapy. His colitis responded rapidly to the ciclosporin and he was converted to oral preparation. Following further neurological physiotherapy input with regards to his mild-moderate expressive language difficulty he was discharged home 27 d after his admission.

5-ASA have been shown to be efficacious in active Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis, for inducing remission in ulcerative colitis[2,3] and are generally regarded as safe and well tolerated medications. Whilst the rate of reported common side effects including headache, dyspepsia or nausea can be high, one systematic review showed that the rate of adverse events or withdrawal from treatment is actually comparable to placebo[4]. Serious reactions are far rarer, but recognised side effects include pancreatitis, interstitial nephritis, blood dyscrasias and Stevens Johnson syndrome. Cardiac side effects from 5-ASA agents are extremely uncommon.

Acute cardiac complications in inflammatory bowel disease are also uncommon[5]. The most commonly reported complication is pericarditis, and in many cases this has been linked to the medications used to manage the disease[6]. In rare circumstance myocarditis has been described as a manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease (Table 1) however the temporal relationship with the onset of our patients’ symptoms and the start of his medication would indicate a causal relationship.

| Case report | Brief summary |

| Ulcerative colitis | |

| [7] | Fatal giant cell myocarditis after colectomy for ulcerative colitis |

| [8] | Idiopathic giant-cell myocarditis-natural history and treatment. Describes two cases of myocarditis in ulcerative colitis |

| [9] | Giant cell myocarditis monocytic immunophenotype of giant cells in a case associated with ulcerative colitis |

| [10] | Ulcerative colitis complicated by myopericarditis and complete artioventricular block |

| [11] | Myopericarditis complicating ulcerative colitis |

| [12] | Acute peri-myocarditis in ulcerative colitis |

| [13] | Transient myocarditis associated with fulminant colitis |

| [14] | Giant cell myocarditis (subacute congestive heart failure in context of colitis) |

| [15] | Fatal giant-cell myocarditis complicated with ulcerative colitis |

| Crohn’s Disease | |

| [16] | A Case of Acute Myocarditis as the Initial Presentation of Crohn's Disease |

| [8] | Idiopathic giant-cell myocarditis-natural history and treatment. Describes one case of myocarditis in crohn’s disease |

| [17] | Transmural inflammation consisting of lymphocytic infiltration in context of severe malnutrition leading to sudden death in Crohn´s Disease |

| [18] | Myocarditis and subcutaneous granulomas in a patient with Cohn’s disease of the colon |

| [19] | Myocarditis in children with inflammatory bowel disease |

Cardiac hypersensitivity to 5-ASA therapy has been reported in a small number of case studies. It was first suggested in the Lancet in 1989, where a possible myocarditis was proposed[20], and the first reported death from myocarditis associated with mesalazine was in 1990[21]. The exact mechanism by which mesalazine causes a myocarditis has not been clearly determined, but a hypersensitivity reaction with eosinophilic infiltration has been proposed[22-24].

The temporal relationship between this otherwise fit and well young patient developing rapidly progressive and severe cardiomyopathy with resultant cardiogenic shock soon after starting on mesalazine strongly suggests a link between the disease process or treatment. The onset of cardiac symptoms and impaired function correlate with the starting of 5-ASA treatment and the subsequent improvement shortly after cessation, despite a relative worsening in his ulcerative colitis over the same period would strengthen the case for medication being the culprit. Whilst the cardiac MRI and biopsy do not show definitive evidence of myocarditis and the rapidity of cardiac deterioration contrasting with previous reports suggesting a typical period of two weeks following commencement of treatment prior to presentation, with some even up to years after starting 5-ASAs, there are limited numbers of cases reported so far and the rapid improvement on cessation of therapy, as in this case, is more typical[25].

5-ASA agents are both efficacious and generally safe in the management of inflammatory bowel disease, and whilst serious and potentially life-threatening complications may occur, these are very rare and should not necessarily discourage their use. This case aims to highlight and raise awareness of one such potential complication to ensure its consideration, prompt recognition and diagnosis in the future.

Acute myocarditis post mesalamine treatment leading to cardiogenic shock in severe ulcerative colitis.

Chest pain very short followed by cardiogenic shock requiring inotropic support.

Viral myocarditis, autoimmune myocarditis.

Raised troponin and inflammatory markers at diagnosis with a negative acute virology screen only revealing past EBV and parvovirus infection.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showing diffuse, heterogeneous enhancement of the left and right ventricular myocardium.

Cardiac biopsy showing several capillaries distended with microthrombi, myocyte vacuolation, interstitial oedema and focal haemorrhage with Colonic biopsy showing moderate active chronic colitis.

This gentleman underwent a very short course of high dose mesalamine therapy.

There are a small number of five-amino salicylic acids (5-ASA) induced myocarditis cases in inflammatory bowel disease, however the mechanism is not well understood and it remains a serious but rare occurrence.

STIR2 imaging - Short tau inversion recovery, a fat suppression technique to better distinguish tissue components.

This case report highlights a rare but potentially life threatening adverse effect of 5-ASA treatment for ulcerative colitis.

This is an interesting case of a rare side effect of a drug which is usually thought to be a “benign” agent. It is well written.

P- Reviewer: Ahluwalia NK, Desai DC, Meucci G, Shussman N S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Carter MJ, Lobo AJ, Travis SP. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2004;53 Suppl 5:V1-V16. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 746] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 753] [Article Influence: 37.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hanauer SB, Strömberg U. Oral Pentasa in the treatment of active Crohn’s disease: A meta-analysis of double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:379-388. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 175] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sutherland L, MacDonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;CD000543. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Loftus EV, Kane SV, Bjorkman D. Systematic review: short-term adverse effects of 5-aminosalicylic acid agents in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:179-189. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Tsianos EV, Katsanos KH. The heart in inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Gastroentol. 2002;15:124-133. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Dubowitz M, Gorard DA. Cardiomyopathy and pericardial tamponade in ulcerative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:1255-1258. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | McKeon J, Haagsma B, Bett JH, Boyle CM. Fatal giant cell myocarditis after colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Am Heart J. 1986;111:1208-1209. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cooper LT, Berry GJ, Shabetai R. Idiopathic giant-cell myocarditis--natural history and treatment. Multicenter Giant Cell Myocarditis Study Group Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1860-1866. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 512] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 566] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ariza A, López MD, Mate JL, Curós A, Villagrasa M, Navas-Palacios JJ. Giant cell myocarditis: monocytic immunophenotype of giant cells in a case associated with ulcerative colitis. Hum Pathol. 1995;26:121-123. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Thuesen L, Sørensen J. [Ulcerative colitis complicated by myopericarditis and complete atrioventricular block]. Ugeskr Laeger. 1979;141:2760-2761. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Mowat NA, Bennett PN, Finlayson JK, Brunt PW, Lancaster WM. Myopericarditis complicating ulcerative colitis. Br Heart J. 1974;36:724-727. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Seitz R, Wehr M. [Acute peri-myocarditis in ulcerative colitis]. Internist (Berl). 1980;21:760-763. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Williamson JM, Dalton RS. Transient myocarditis associated with fulminant colitis. ISRN Surg. 2011;2011:652798. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mohite PN, Zych B, Popov AF, Banner NR, Simon AR. Successful treatment of ulcerative colitis-related fulminant myocarditis using extracorporeal life support. Heart Surg Forum. 2013;16:E208-E209. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nakamura F, Nakashima Y, Takeuchi T, Tomida T, Naruse K, Ohno O, Okamura S, Maeda M. [Fatal giant-cell myocarditis complicated with ulcerative colitis]. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 2006;95:1112-1114. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Oh IS, Choi CH, Park JH, Kim JW, Cha BK, Do JH, Chang SK, Kwon GY. A case of acute myocarditis as the initial presentation of Crohn’s disease. Gut Liver. 2012;6:512-515. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hitosugi M, Kitamura O, Takatsu A. Sudden death of a patient with Crohn’s disease. Nihon Hoigaku Zasshi. 1998;52:211-214. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Weiss N, Rademacher A, Zoller WG, Schlöndorff D. Myocarditis and subcutaneous granulomas in a patient with Crohn’s disease of the colon. Am J Med. 1995;99:434-436. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Frid C, Bjarke B, Eriksson M. Myocarditis in children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1986;5:964-965. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Agnholt J, Sørensen HT, Rasmussen SN, Gøtzsche CO, Halkier P. Cardiac hypersensitivity to 5-aminosalicylic acid. Lancet. 1989;1:1135. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kristensen KS, Høegholm A, Bohr L, Friis S. Fatal myocarditis associated with mesalazine. Lancet. 1990;335:605. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Galvão Braga C, Martins J, Arantes C, Ramos V, Vieira C, Salgado A, Magalhães S, Correia A. Mesalamine-induced myocarditis following diagnosis of Crohn’s disease: a case report. Rev Port Cardiol. 2013;32:717-720. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Robertson E, Austin D, Jamieson N, Hogg KJ. Balsalazide-induced myocarditis. Int J Cardiol. 2008;130:e121-e122. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | García-Ferrer L, Estornell J, Palanca V. Myocarditis by mesalazine with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1015. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Merceron O, Bailly C, Khalil A, Pontnau F, Hammoudi N, Dorent R, Michel PL. Mesalamine-induced myocarditis. Cardiol Res Pract. 2010;2010. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |