Published online Mar 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i9.2412

Revised: December 3, 2013

Accepted: January 2, 2014

Published online: March 7, 2014

Processing time: 130 Days and 15.2 Hours

AIM: To investigate the efficacy of adding prokinetics to proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

METHODS: PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Web of Knowledge databases (prior to October 2013) were systematically searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared therapeutic efficacy of PPI alone (single therapy) or PPI plus prokinetics (combined therapy) for GERD. The primary outcome of those selected trials was complete or partial relief of non-erosive reflux disease symptoms or mucosal healing in erosive reflux esophagitis. Using the test of heterogeneity, we established a fixed or random effects model where the risk ratio was the primary readout for measuring efficacy.

RESULTS: Twelve RCTs including 2403 patients in total were enrolled in this study. Combined therapy was not associated with significant relief of symptoms or alterations in endoscopic response relative to single therapy (95%CI: 1.0-1.2, P = 0.05; 95%CI: 0.66-2.61, P = 0.44). However, combined therapy was associated with a greater symptom score change (95%CI: 2.14-3.02, P < 0.00001). Although there was a reduction in the number of reflux episodes in GERD [95%CI: -5.96-(-1.78), P = 0.0003] with the combined therapy, there was no significant effect on acid exposure time (95%CI: -0.37-0.60, P = 0.65). The proportion of patients with adverse effects undergoing combined therapy was significantly higher than for PPI therapy alone (95%CI: 1.06-1.36, P = 0.005) when the difference between 5-HT receptor agonist and PPI combined therapy and single therapy (95%CI: 0.84-1.39, P = 0.53) was excluded.

CONCLUSION: Combined therapy may partially improve patient quality of life, but has no significant effect on symptom or endoscopic response of GERD.

Core tip: Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are generally accepted as the standard treatment of care for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). However, many patients undergoing PPI treatment have no effective symptomatic relief. Although many studies have shown the clinical efficacy of adding prokinetics to PPI therapy in GERD, others have shown no therapeutic benefit. The efficacy and safety of combined prokinetic and PPI therapy for GERD remain controversial. In this retrospective meta-analysis, we find no advantage for the addition of prokinetics to a PPI therapeutic regimen, relative to PPI alone. However, combination therapy may improve symptom score and patient quality of life.

- Citation: Ren LH, Chen WX, Qian LJ, Li S, Gu M, Shi RH. Addition of prokinetics to PPI therapy in gastroesophageal reflux disease: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(9): 2412-2419

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i9/2412.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i9.2412

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common condition affecting 10%-20% of Europeans[1] and 3%-7% of Asians[2]. Based on an endoscopy study, the prevalence of erosive reflux esophagitis (RE), a chronic form of GERD associated with damage to the esophagus, ranges from 6% to 10% in Asia[3]. Since RE is more likely to be detected by endoscopy than non-erosive reflux disease (NERD), the incidence of RE is higher than that of NERD. Symptoms of GERD, which include heartburn, non-cardiac chest pain, acid regurgitation, chronic cough, bloating and belching, may seriously affect quality of life of some patients. Furthermore, GERD is linked with serious complications, such as hemorrhage, peptic stricture, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma[3-5]. Both NERD and RE are subtypes of GERD. NERD presents clinically with acid reflux and heartburn with no mucosal break, whereas RE patients have mucosal damage detectable by endoscopy[6]. The mechanisms underlying GERD may include esophageal hypersensitivity and transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation (TLESR)[7]. Studies show that changes in diet, physical activity, and BMI increase the risk for GERD[3]. NERD may be due to visceral hypersensitivity, prolonged contraction of the lower esophagus, and other psychological factors[8].

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are generally accepted as the standard treatment paradigm for GERD. Although many patients with RE have symptomatic relief with this drug alone[9], many patients have no symptomatic resolution[10-13]. Overall, 30% of GERD patients, 10%-15% of RE patients, and 40%-50% of NERD patients do not experience symptom alleviation with conventional PPI therapy[14-16]. New PPI formulations and regenerative types of acid-suppressive drugs for GERD are urgently needed.

Prokinetics are agents that increase lower esophageal sphincter pressure (LESP), enhance esophageal peristalsis, and augment gastric emptying. These include 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) receptor agonists, GABA-B receptor agonists, dopamine receptor antagonists, and others. Five-HT receptor agonists increase acetylcholine release from parasympathetic nerve roots and promote gastric emptying and bowel motility[14,17], and are frequently used in combination with PPI therapy. Cisapride is a canonical prokinetic agent with equal efficacy as a 5-HT4 receptor agonist and a H2 histamine receptor antagonist. In addition to protecting the esophageal mucosa, it was reported that cisapride increased LEST and esophageal peristaltic amplitude; however, cisapride is now prohibited in Europe due to its detrimental side effects on the cardiac system[18]. Mosapride, another 5-HT4 agonist, is a structural analog of cisapride with less cardiac side effects[19,20]. It has been approved in Asia for the treatment of some functional gastrointestinal disorders, such as functional dyspepsia. Baclofen and lesogaberan (AZD 3355) were developed as selective GABA-B agonists based on their inhibition of TLESR and reflux episodes[21]. A phase II study reported that lesogaberan combined with PPI modestly improved GERD symptoms[22], but its efficacy and safety were not determined.

Although many studies have shown that addition of a prokinetic to PPI can improve the symptoms of GERD, there is still some controversy in the literature. The efficacy and safety profiles of combination prokinetics and PPI therapy regimens relative to PPI monotherapy for GERD remain unclear. Here, we performed a retrospective meta-analysis to identify the efficacy and safety of these two types of treatments in GERD.

All eligible articles in English published prior to October 2013 were searched from PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Web of Knowledge. The search strategy consisted of a combination of the following MESH terms and text words: gastroesophageal reflux diseases, GERD, non-erosive reflux diseases, NERD, reflux esophagitis, RE, proton pump inhibitors, PPI, prokinetics, and GABA-B receptor agonists. A Cochrane filter for identifying randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was applied to the search results, and all potentially relevant abstracts and citations were retrieved for further review. Furthermore, we searched the bibliographies of selected trials obtained through the electronic screen to identify additional studies of interest.

Articles were eligible for inclusion in this meta-analysis if they met the following criteria: (1) Participants were diagnosed with GERD (RE or NERD); (2) Participants were 18 years or older; (3) Patients receiving PPI monotherapy were compared with patients receiving combined prokinetic and PPI therapy; (4) The study was a RCT; (5) Criteria for successful treatment were clearly defined; and (6) Treatment lasted for two or more weeks.

Publications were excluded according to the following criteria: (1) Studies comparing H2 receptor antagonist plus prokinetic to H2 receptor antagonist; (2) Participants with complications in addition to GERD; and (3) Missing or unclear data for final outcomes of interest.

To avoid bias in the data abstraction process, two investigators (Ren LH and Chen WX) independently abstracted the data, recorded the first author, year of study, study design, and study population characteristics, and compared the results. All data were checked by a third reviewer and disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Appropriate RCTs were included, and Review Manager Version 5.1 (The Cochran Collaboration, Oxford, England) was used for preparation of the review. Stata 12.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States) was used for statistical analysis. The risk ratio of data was estimated by the Mantel-Haenszel χ2 method, where P values < 0.05 were considered significantly different. Study heterogeneity was evaluated by Cochran I2 statistics, where I2 < 50% indicated a lack of heterogeneity. If significant heterogeneity was found, a random effects model was applied for evaluation of the pooled data; otherwise, a fixed effects model was used. Possible publication bias was assessed by Egger’s and Begg’s funnel plots, where P values < 0.05 indicated little publication bias.

Twelve RCTs met the inclusion criteria, and characteristics of each study are presented in Table 1. In total, there were 2403 enrolled participants in the trials who were treated with 5-HT agonists, GABA-B receptor agonists, dopamine-receptor antagonists, and placebo control. Combination 5-HT agonist and PPI therapy was given in seven trials, combination GABA-B receptor agonist and PPI therapy in four trials, and combination dopamine-receptor antagonist and PPI therapy in one trial. In all RCTs, monotherapy was directly compared with combination PPI therapy. In the 5-HT agonist studies, the doses of PPI and mosapride or cisapride were the same across patients. However, in the GABA-B receptor agonist studies, different kinds of PPI and variable doses of baclofen or lesogaberan were used. All trials included mild to moderate GERD patients, with severe participants divided into a subgroup. The primary endpoints evaluated in these trials were symptom or endoscopic response, and the relief score was used to determine the symptomatic remission.

| Ref. | Country | Participants (n) | Duration of study | Female | Age (yr) | BMI (kg/m2) |

| Vakil et al[23], 2013 | United States | 460 | 6 wk | 254 (55.2) | 44 | 28 |

| Cho et al[24], 2013 | South Korea | 50 | 4 wk | 26 (52.0) | 46 | 21 |

| Shaheen et al[28], 2013 | United States | 661 | 4 wk | 376 (56.9) | 48 | 28 |

| Ndraha et al[29], 2011 | Indonesia | 60 | 2 wk | 40 (66.7) | 42 | 24 |

| Hsu et al[2], 2010 | Taiwan | 96 | 8 wk | 48 (50.0) | 47 | 24 |

| Boeckxstaens et al[22], 2011 | United States | 244 | 4 wk | 82 (33.6) | 50 | 27 |

| Miwa et al[12], 2011 | Japan | 200 | 4 wk | 120 (60.0) | 52 | 22 |

| Beaumont et al[27], 2009 | United States | 16 | 2 wk | 8 (50.0) | 54 | Not reported |

| Madan et al[19], 2004 | India | 68 | 8 wk | 23 (33.8) | 35 | Not reported |

| Smythe et al[30], 2003 | United Kingdom | 23 | 4 wk | 3 (13.0) | 62 | Not reported |

| van Rensburg et al[25], 2001 | United Kingdom | 350 | 8 wk | 213 (60.9) | 47 | 28 |

| Vigneri et al[26], 1995 | Italy | 175 | 12 mo | 58 (33.1) | 45 | Not reported |

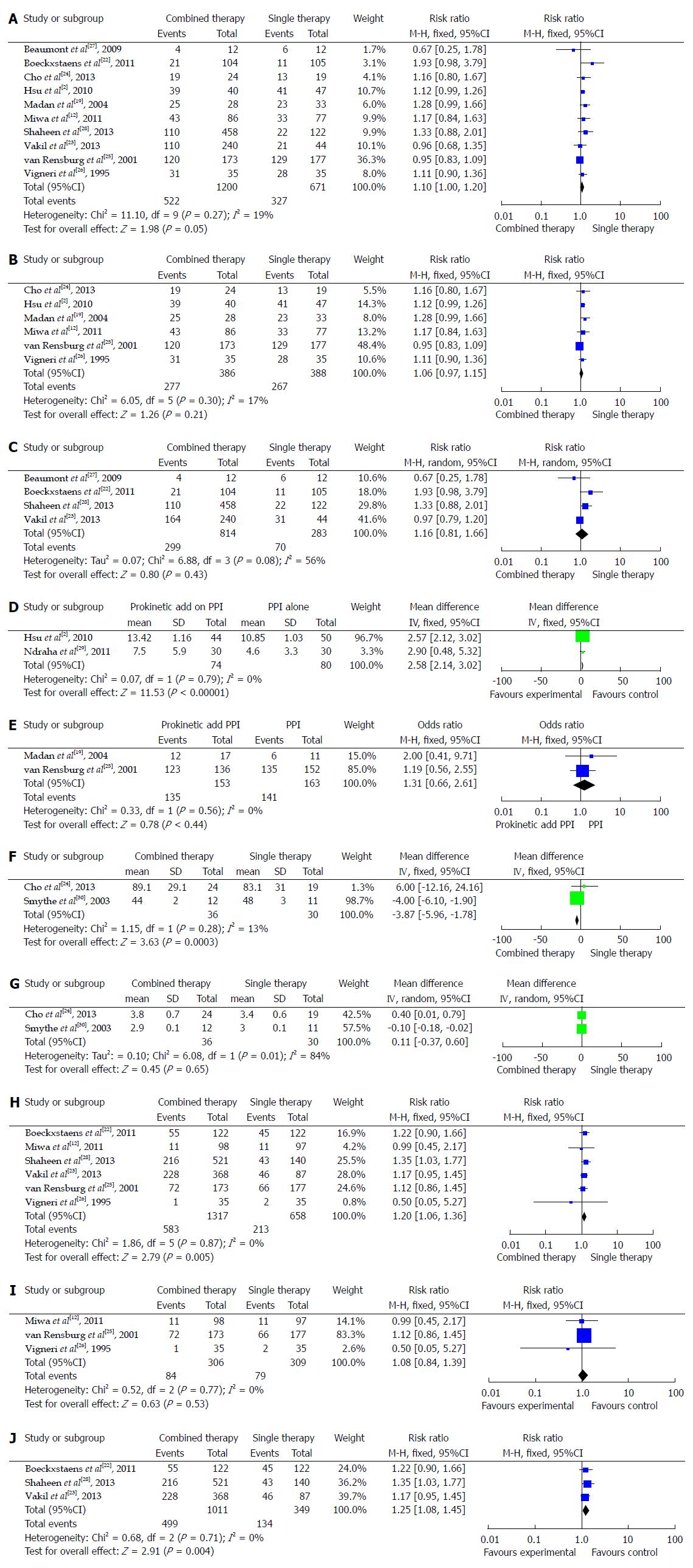

Table 2 details the symptom response in ten studies. Six trials[2,13,20,25-27] compared the addition of mosapride or cisapride to PPI therapy to PPI alone therapy, and four trials[23,24,28,29] compared baclofen or lesogaberan to placebo PPI control. There was no statistically significant difference in symptom response between combined therapy and single therapy in these ten trials (95%CI: 1.0-1.2, P = 0.05) (Figure 1A). Furthermore, we divided those ten trials into a 5-HT agonist group and a GABA-B receptor agonist group and found that neither group displayed significant differences between combination and mono-therapy for symptom response (95%CI: 1.0-1.2, P = 0.21; 95%CI: 0.8-1.7, P = 0.40) (Figure 1B and C).

| Reference | Intervention | Combined therapy, improved/treated | Single therapy, improved/treated |

| Cho et al[24], 2013 | Esomeprazole 40 mg/d + mosapride 30 mg tid | 19/24 | 13/19 |

| Hsu et al[2], 2010 | Lansoprazole 30 mg/d + mosapride 5 mg tid | 39/44 | 41/50 |

| Madan et al[19], 2004 | Pantoprazole 40 mg bid + mosapride 5 mg tid | 25/28 | 23/33 |

| Miwa et al[12], 2011 | Omeprazole 10 mg/d+ mosapride 5 mg tid | 45/97 | 42/95 |

| van Rensburg et al[25], 2001 | Pantoprazole 40 mg/d + cisapride 20 mg bid | 120/173 | 129/177 |

| Vigneri et al[26], 1995 | Omeprazole 40 mg/d + cisapride 10 mg tid | 31/35 | 28/35 |

| Beaumont et al[27], 2009 | PPI + baclofen 20 mg tid | 4/12 | 6/12 |

| Boeckxstaens et al[22], 2011 | PPI + lesogaberan 65 mg bid | 21/104 | 11/105 |

| Shaheen et al[28], 2013 | PPI + lesogaberan 60/120/180/240 mg bd | 110/458 | 22/122 |

| Vakil et al[23], 2013 | PPI + baclofen 20/40/60 mg qd | 110/240 | 21/54 |

The 5-HT receptor agonist group showed a change in symptom score in the two treatment groups, even though the symptom assessments were different. Since Ndraha[29] and Hsu et al[2] used the frequency scale for the symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux (FSSG) score, we combined the two trials to assess the change in symptom score. Combination therapy yielded more symptomatic relief relative to monotherapy (95%CI: 2.1-3.0, P < 0.00001) (Figure 1D). Although symptom response in these two treatment groups was not statistically different, the clinical symptoms in the combination therapy group were relieved more than the single therapy group. Overall, these findings suggest that combined therapy may have improved patient quality of life.

To explore the mucosal healing in RE patients, we investigated the endoscopic response in two trials[19,25] where endoscopic response was reported. Overall, the endoscopic response in RE patients was not significantly different between 5-HT agonist and PPI combined therapy and PPI single therapy (95%CI: 0.7-2.6, P = 0.44) (Figure 1E).

Two trials[24,29] reported LESP, reflux wave amplitude, and wave duration. As shown in Figure 1F, combined therapy may reduce reflux wave amplitude [95%CI: -6.0-(-1.8), P = 0.0003] but not wave duration (95%CI: -0.4-0.6, P = 0.65) (Figure 1G). Taken together, these findings suggest that combined therapy in GERD may reduce the number of reflux episodes but not the duration of acid exposure time.

Combined prokinetic and PPI therapy may be linked to additional side effects, such as reflux, abdominal pain, indigestion, diarrhea, chest pain, and constipation. Since only six of the 12 trials reported adverse effects, we only included these studies in our proportional analysis. The side-effects ratio demonstrated that side effects were elevated in patients with combined relative to single PPI therapy (95%CI: 1.06-1.36, P = 0.005) (Figure 1H). To further explore the side-effects of the 5-HT group, we excluded the GABA-B receptor agonists group. However, we found no difference between the two therapies for the 5-HT agonist group (95%CI: 0.84-1.39, P = 0.53) (Figure 1I). Single side-effects ratio in the GABA-B receptor agonist group was evaluated, and there were significantly more side effects in the GABA-B receptor agonists combined group than in the group with PPI therapy alone (95%CI: 1.1-1.5, P = 0.004) (Figure 1J).

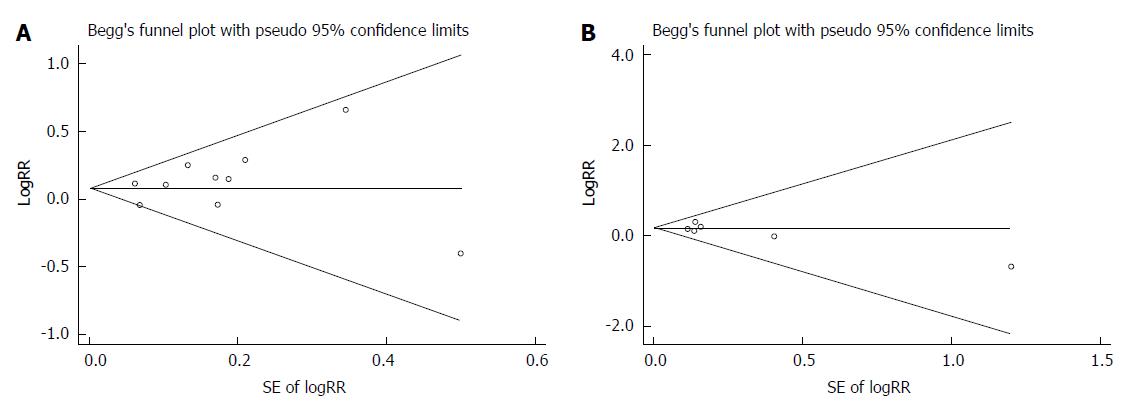

As shown in Figure 2, no publication bias was detected in symptom response (Egger’s test P = 0.333; Begg’s test P = 0.721) or adverse event proportion (Egger’s test P = 0.246; Begg’s test P = 0.452).

Previous studies have reported that PPI therapy was more effective than H2R agonists and prokinetics for GERD[4], but none had investigated the efficacy of combined prokinetic and PPI therapy. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we demonstrated that combination prokinetic and PPI therapy was no more efficacious than PPI alone for GERD. This therapy did improve patients’ reported symptoms score, suggesting that it may enhance patient quality of life.

Since the 1990s, PPIs have been the mainstay treatment for GERD[31] even though a large number of patients fail to improve with a standard single PPI therapy[7]. Approximately 15% of eosinophilic esophagitis (EE) patients (mainly of Los Angeles grades C and D), 20% of Barrett’s esophagus (BE) patients, 40%-50% of NERD patients[15], and up to 40% of patients with extra-esophageal manifestations of GERD[32] did not therapeutically benefit from standard PPI therapy. Recently, a number of studies found that PPIs are less effective for NERD than RE[10,13,15,33], but the underlying mechanism remains unknown.

Hiyama et al[34] evaluated whether Heliobacter pylori infection and sex may contribute to attenuated PPI efficacy in NERD. Miyamoto et al[33] identified younger age, constipation, and GI dysmotility as potential influencing factors of PPI non-responsiveness in NERD. Adding a prokinetic to PPI may partly alleviate symptoms of NERD, but there is little evidence available regarding an impact on mucosal healing[35]. However, Koshino et al[16] demonstrated that mosapride (15 mg/d) did not change salivary secretion and esophageal motility in healthy volunteers.

There are available different PPIs for the treatment of GERD, including omeprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole, pantoprazole, esomeprazole, and others. Meta-analyses failed to reveal a difference in efficacy for symptom relief among various PPIs[36]. Prokinetics in addition to PPI therapy may be a new treatment paradigm for PPI-non responsive patients. The GABA-B agonists, baclofen and lesogaberan, were reported to be effective in treating GERD by reducing LES pressure, LES relaxations, and acid reflux episodes[37]. Unfortunately, its clinical use is limited by side effects, including dizziness and constipation[9].

Here, we analyzed 12 RCTs to determine the therapeutic benefit of combination prokinetic and PPI therapy over PPI therapy alone. We found no significant difference between these two groups regarding symptom or endoscopic response. When we divided these 12 trials into two groups, according to 5-HT agonist and GABA-B agonist, we still did not find any difference between the combination and single therapy groups. Regarding adverse events, GABA-B agonists, but not 5-HT agonists, were associated with increased frequency of adverse effects. In terms of symptom score change, combined therapy may improve patient quality of life by decreasing the number of reflux episodes, although acid exposure time was unaltered.

There are some limitations of our meta-analysis to consider. First, PPI and prokinetic therapies in the 12 trials were not identical. Although one study found little impact on symptom response[36], we cannot rule out the possibility of treatment course affecting this measure. To limit this complication, we only chose studies for this analysis with a treatment course for GERD longer than two weeks. Second, an inherent weakness of all systematic reviews and meta-analyses is the possibility that some studies failed to find significant symptom improvement in the peer-reviewed literature[38], thereby leading us to underestimate the main effect. To overcome these limitations, long-term RCTs need to be performed with a larger quantity of participants to more effectively determine efficacy and safety profiles of combined prokinetic and PPI therapy.

In summary, patients with GERD respond to combined prokinetic and PPI therapy. Combination therapy may improve patient quality of life, although there was no significant difference in symptom or endoscopic responses. Side effects of combined therapy may be greater than single therapy, especially with GABA-B agonists. Whether prokinetic plus PPI is indeed therapeutically efficacious for GERD will require future trials.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common disease, affecting individuals of all nationalities. The standard treatment regimen is proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Despite this therapy, many patients remain symptomatic. The addition of prokinetics to PPI therapy may improve the symptoms of GERD in these patients, but the efficacy and safety of prokinetics remain to be established.

This meta-analysis was performed to assess the efficacy and safety of PPI mono-therapy versus combined therapy in patients with GERD. The main measured outcomes are as follows: symptom response, symptoms score change, endoscopic response, wave amplitude, wave duration, and adverse events.

Authors found with this meta-analysis no demonstrable effect of either combination therapy for relief of symptoms or alteration in endoscopic response. However, with combination therapy there was a greater symptom score change, suggesting that this therapy did improve patient quality of life.

Authors’ results suggest that combination therapy may have some advantages for symptomatic or endoscopic response relative to PPI alone. There is some evidence that combination therapy may partially improve patient quality of life. Until further randomized controlled trails with a large population number are carried out, authors suggest use of combination therapy on an individual basis.

FSSG score: a questionnaire given to GERD patients in order to assess severity of symptoms, based on a frequency scale for symptoms of GERD.

The efficacy and safety for the use of prokinetics plus PPI compared to PPI monotherapy for GERD remain unclear. Therefore, the authors conducted a meta-analysis to determine the efficacy and safety of these two treatment regimens for GERD. The authors concluded that combination therapy may partially improve the patient quality of life (symptoms score change, reflux wave amplitude, and wave duration).

P- Reviewer: Bener A S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1256] [Cited by in RCA: 1262] [Article Influence: 63.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hsu YC, Yang TH, Hsu WL, Wu HT, Cheng YC, Chiang MF, Wang CS, Lin HJ. Mosapride as an adjunct to lansoprazole for symptom relief of reflux oesophagitis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:171-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Goh KL. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asia: A historical perspective and present challenges. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26 Suppl 1:2-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | van Pinxteren B, Sigterman KE, Bonis P, Lau J, Numans ME. Short-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists and prokinetics for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-like symptoms and endoscopy negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD002095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lagergren J, Bergström R, Lindgren A, Nyrén O. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:825-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2115] [Cited by in RCA: 2028] [Article Influence: 78.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hiyama T, Yoshihara M, Tanaka S, Haruma K, Chayama K. Strategy for treatment of nonerosive reflux disease in Asia. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3123-3128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Altan E, Blondeau K, Pauwels A, Farré R, Tack J. Evolving pharmacological approaches in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2012;17:347-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Futagami S, Iwakiri K, Shindo T, Kawagoe T, Horie A, Shimpuku M, Tanaka Y, Kawami N, Gudis K, Sakamoto C. The prokinetic effect of mosapride citrate combined with omeprazole therapy improves clinical symptoms and gastric emptying in PPI-resistant NERD patients with delayed gastric emptying. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:413-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:308-328; quiz 329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1136] [Cited by in RCA: 1120] [Article Influence: 93.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang C, Hunt RH. Medical management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37:879-899, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Heidelbaugh JJ, Nostrant TT, Kim C, Van Harrison R. Management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:1311-1318. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Miwa H, Inoue K, Ashida K, Kogawa T, Nagahara A, Yoshida S, Tano N, Yamazaki Y, Wada T, Asaoka D. Randomised clinical trial: efficacy of the addition of a prokinetic, mosapride citrate, to omeprazole in the treatment of patients with non-erosive reflux disease - a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:323-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bruley des Varannes S, Coron E, Galmiche JP. Short and long-term PPI treatment for GERD. Do we need more-potent anti-secretory drugs. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:905-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dean BB, Gano AD, Knight K, Ofman JJ, Fass R. Effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in nonerosive reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:656-664. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Fass R, Shapiro M, Dekel R, Sewell J. Systematic review: proton-pump inhibitor failure in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease--where next. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:79-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Koshino K, Adachi K, Furuta K, Ohara S, Morita T, Nakata S, Tanimura T, Miki M, Kinoshita Y. Effects of mosapride on esophageal functions and gastroesophageal reflux. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1066-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sanger GJ. Translating 5-HT receptor pharmacology. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:1235-1238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Quigley EM. Cisapride: what can we learn from the rise and fall of a prokinetic. J Dig Dis. 2011;12:147-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Madan K, Ahuja V, Kashyap PC, Sharma MP. Comparison of efficacy of pantoprazole alone versus pantoprazole plus mosapride in therapy of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a randomized trial. Dis Esophagus. 2004;17:274-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tack J, Camilleri M, Chang L, Chey WD, Galligan JJ, Lacy BE, Müller-Lissner S, Quigley EM, Schuurkes J, De Maeyer JH. Systematic review: cardiovascular safety profile of 5-HT(4) agonists developed for gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:745-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Blackshaw LA. Receptors and transmission in the brain-gut axis: potential for novel therapies. IV. GABA(B) receptors in the brain-gastroesophageal axis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G311-G315. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Boeckxstaens GE, Beaumont H, Hatlebakk JG, Silberg DG, Björck K, Karlsson M, Denison H. A novel reflux inhibitor lesogaberan (AZD3355) as add-on treatment in patients with GORD with persistent reflux symptoms despite proton pump inhibitor therapy: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Gut. 2011;60:1182-1188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Vakil NB, Huff FJ, Cundy KC. Randomised clinical trial: arbaclofen placarbil in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease--insights into study design for transient lower sphincter relaxation inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:107-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cho YK, Choi MG, Park EY, Lim CH, Kim JS, Park JM, Lee IS, Kim SW, Choi KY. Effect of mosapride combined with esomeprazole improves esophageal peristaltic function in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a study using high resolution manometry. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1035-1041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | van Rensburg CJ, Bardhan KD. No clinical benefit of adding cisapride to pantoprazole for treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:909-914. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Vigneri S, Termini R, Leandro G, Badalamenti S, Pantalena M, Savarino V, Di Mario F, Battaglia G, Mela GS, Pilotto A. A comparison of five maintenance therapies for reflux esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1106-1110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 397] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Beaumont H, Boeckxstaens GE. Does the presence of a hiatal hernia affect the efficacy of the reflux inhibitor baclofen during add-on therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1764-1771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Shaheen NJ, Denison H, Björck K, Karlsson M, Silberg DG. Efficacy and safety of lesogaberan in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2013;62:1248-1255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ndraha S. Combination of PPI with a prokinetic drug in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Acta Med Indones. 2011;43:233-236. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Smythe A, Bird NC, Troy GP, Ackroyd R, Johnson AG. Does the addition of a prokinetic to proton pump inhibitor therapy help reduce duodenogastro-oesophageal reflux in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:305-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Horn J. The proton-pump inhibitors: similarities and differences. Clin Ther. 2000;22:266-280; discussion 265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Moore JM, Vaezi MF. Extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease: real or imagined. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:389-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Miyamoto M, Manabe N, Haruma K. Efficacy of the addition of prokinetics for proton pump inhibitor (PPI) resistant non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) patients: significance of frequency scale for the symptom of GERD (FSSG) on decision of treatment strategy. Intern Med. 2010;49:1469-1476. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Hiyama T, Matsuo K, Urabe Y, Fukuhara T, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Haruma K, Chayama K. Meta-analysis used to identify factors associated with the effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors against non-erosive reflux disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1326-1332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Manzotti ME, Catalano HN, Serrano FA, Di Stilio G, Koch MF, Guyatt G. Prokinetic drug utility in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux esophagitis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Open Med. 2007;1:e171-e180. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Gralnek IM, Dulai GS, Fennerty MB, Spiegel BM. Esomeprazole versus other proton pump inhibitors in erosive esophagitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1452-1458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Grossi L, Spezzaferro M, Sacco LF, Marzio L. Effect of baclofen on oesophageal motility and transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations in GORD patients: a 48-h manometric study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:760-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Thornton A, Lee P. Publication bias in meta-analysis: its causes and consequences. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:207-216. [PubMed] |