Published online Feb 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i6.1626

Revised: October 16, 2013

Accepted: November 18, 2013

Published online: February 14, 2014

Processing time: 175 Days and 14.1 Hours

Perforation of the gastrointestinal tract by ingested foreign bodies is extremely rare in otherwise healthy patients, accounting for < 1% of cases. Accidentally ingested foreign bodies could cause small bowel perforation through a hernia sac, Meckel’s diverticulum, or the appendix, all of which are uncommon. Despite their sharp ends and elongated shape, bowel perforation caused by ingested fish bones is rarely reported, particularly in patients without intestinal disease. We report a case of 57-year-old female who visited the emergency room with periumbilical pain and no history of underlying intestinal disease or intra-abdominal surgery. Abdominal computed tomography and exploratory laparotomy revealed a small bowel micro-perforation with a 2.7-cm fish bone penetrating the jejunal wall.

Core tip: A healthy patient who had no intestinal disease or history of abdominal surgery was admitted with abdominal pain. The computer tomography scan showed a small quantity of free air with mesentery, suggesting microperforation. An emergency exploratory laparotomy was performed, and microperforation at the mid-portion of the jejunum caused by an ingested fish bone was revealed.

- Citation: Choi Y, Kim G, Shim C, Kim D, Kim D. Peritonitis with small bowel perforation caused by a fish bone in a healthy patient. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(6): 1626-1629

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i6/1626.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i6.1626

Perforation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract by ingested foreign bodies is extremely rare but can occur in patients with a hernia sac or Meckel’s diverticulum. Approximately 75% of ingested foreign bodies are impacted at the cricopharyngeal sphincter of the esophagus, and > 90% of foreign bodies pass through the intestine if they reach the stomach, with only a few causing impaction and severe complications[1]. There is a report of a 13-cm-long artificial esophageal tube that passed through the entire GI tract without perforation or impaction in an advanced gastric cancer patient with esophageal stenosis[2]. From this perspective, bowel perforation caused by an ingested fish bone is difficult to consider in an otherwise healthy individual. Small bowel perforation may occur if the patient has intestinal disease or the perforation is at a site of acute angulation, such as the ileocecal and rectosigmoid junctions[3-5]. We report a case of small bowel perforation at the mid-portion of the jejunum caused by an ingested fish bone in an otherwise healthy patient, who had no intestinal disease or history of abdominal surgery.

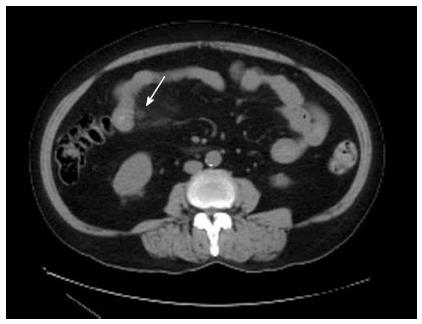

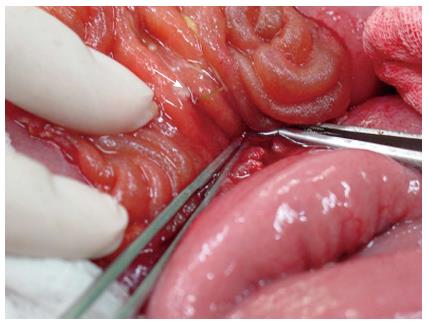

A 57-year-old female, with no previous abdominal complaints, was admitted to our hospital with acute abdominal pain that began 3 d prior with no nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. Physical examination showed diffuse tenderness and rebound tenderness in the entire abdomen with voluntary muscle guarding. Laboratory tests indicated an elevated white cell count of 10610 with 73% neutrophils, and C-reactive protein of 6.30 units. Abdominal X-ray showed paralytic ileus, with multiple small bowel loops and fecal densities in colon. Our presumptive diagnosis was acute peritonitis, based on the patient’s symptoms. Empirical antibiotics were administered immediately, and a computed tomography (CT) imaging study was performed. The CT scan showed a small quantity of free air with mesentery, suggesting microperforation of small bowel (Figure 1). The next day, the white cell count was elevated to 12460, and the pain had deteriorated with a low-grade fever and chills. An emergency exploratory laparotomy was performed, revealing small bowel perforation with a 2.7-cm fish bone at the jejunum, 100 cm above the Treitz ligament (Figure 2). Localized inflammation and abscess formation were identified, and a small bowel segmentectomy was completed. The intestine was grossly normal except for the perforation, and there was no stenosis or angulation at the site of perforation (Figure 3). A retrospective history taken after surgery revealed that the patient had ingested Japanese red rockfish 3 d before admission.

Perforation of the GI tract by ingested foreign bodies is rare, with < 1% of ingested foreign bodies perforating the bowel. Accidentally ingested fish bones are the most common foreign body causing GI tract perforations, but 75% of ingested foreign bodies are impacted at the cricopharyngeal sphincter of the esophagus, and > 90% of foreign bodies pass through the intestine if they reach the stomach[1]. Foreign bodies may perforate the gut through a hernia sac, Meckel’s diverticulum, or the appendix. The terminal ileum is the most common site of perforation, followed by the duodenal C-loop because of the immobile and rigid nature of the duodenum, as well as its deep transverse rugae and sharp angulations, which make it a common site for the entrapment of long and sharp-ended objects[6]. However, impaction and severe complications have few causes; thus, perforation of the bowel with an ingested foreign body in a patient with normal bowel physiology is rarely seen in clinical practice.

The majority of ingested foreign bodies pass through the GI tract without complications and only a minority of cases requires surgical intervention[3-5]. The intestine has a remarkable ability to protect itself against perforation. When the intestinal mucosa is pricked with sharply pointed objects, an area of ischemia with a large central concavity develops at the site. The bowel wall increases the lumen of the bowel at the point of contact, permitting freer progress to the offending object[7]. In addition, when a sharp, long object is swallowed, the flow of the intestinal contents and the relaxation of the bowel wall tend to make the head lead and the sharp end trail behind[8]. However, in this case, the shape of the fish bone apparently made it more likely to be held up in the GI tract. Fish bones produce pathological changes peculiar to its sharp tip, which grips the intestinal wall mucosa and causes necrosis of the intestine that results in the formation of a mucosal band around the fish bone that hooks it to the tissue[9-11]. The bones of Japanese red rockfish are relatively long and sharp, compared with their body length, which could cause severe complications when swallowed. There is no previous report of small bowel perforation caused by Japanese red rockfish, but Kim et al[12] reported that Japanese red rockfish were the second most common fish species causing esophageal perforation. These fish are commonly ingested in East Asia, including South Korea and Japan, so care has to be taken when consuming them.

Perforation of the GI tract has a wide spectrum of clinical presentations, including acute or chronic abdominal pain, GI hemorrhage, bowel obstruction, and even bizarre clinical manifestations such as ureteric colic[13]. Foreign body perforation represents a challenging clinical scenario, and delayed diagnosis of complications and subsequent timely treatment result in increased morbidity and mortality. Although severe tenderness and rebound tenderness suggest bowel perforation, foreign body perforation is seldom diagnosed preoperatively. Non-metallic foreign bodies, especially fish bones and other bone fragments, pose a unique problem in the diagnosis of foreign body perforation. The degree of radio-opacity of the bone depends on the species of fish, and even when fish bones are sufficiently radio-opaque, large soft tissue masses and fluid can obscure the minimal calcium content of the bone, particularly in obese patients[14-15]. The perforation is caused by impaction and progressive erosion of the foreign body through the intestinal wall, and the site of perforation becomes covered by fibrin, omentum or adjacent loops of bowel. Furthermore, the presence of free gas under the diaphragm is rarely seen in foreign body perforation of the GI tract. This limits the contribution and accuracy of CT in preoperative diagnosis, and the prediction of fish bones by symptoms alone or radiographs is quite poor and usually misleading. The use of oral and intravenous contrast material during CT also can cause difficulty in identifying fish bones[16].

Perforation of intestinal structures by ingested foreign bodies is a challenging diagnosis that should always be recalled in cases of acute abdominal symptoms. Japanese red rockfish are commonly ingested in South Korea, and their bones are relatively long and sharp, which can cause complications when swallowed. This is the first reported of bowel perforation caused by Japanese red rockfish bones. The patient experienced bowel perforation at the mid-portion of the jejunum, despite normal bowel physiology with no history of intestinal disease or intra-abdominal surgery. We conclude that bowel perforation caused by a fish bone should be recalled by physicians and a careful history taken if there are symptoms or signs suspicious for peritonitis, even if the CT scan is negative and there are no predisposing factors or previous history of intestinal disease.

Acute peritonitis due to small bowel perforation.

Acute appendicitis [elevated white blood cell (WBC) count, diffuse abdominal pain] - abdominal computed tomography (CT).

WBC 10610 (neutrophil 73%), C-reactive protein 6.30 (mg/dL).

Abdomen X-ray - paralytic ileus (with multiple small bowel loops and fecal densities in colon). Abdomen CT - suggestive of microperforation of small bowel (small quantity of free air with mesentery).

Jejunum, segmental resection: acute nonspecific suppurative inflammation.

Empirical intravenous antibiotics were administered, and emergency exploratory laparotomy with small bowel segmentectomy was performed.

Perforation of intestinal structures by ingested foreign bodies is a challenging diagnosis that should always be recalled in cases of acute abdominal symptoms.

The authors report a very interesting case of small bowel perforation by ingested foreign body. The case presentation and discussion are clear and detailed. Bowel perforation is rarely caused by ingested fish bones and must be taken into account in healthy subjects with acute peritonitis of unknown origin. The case would be of interest for clinicians and surgeons in the management of this kind of patients. However, the plain abdominal film findings could be described (presumably multiple small bowel loops) rather than the singe interpretative statement.

P- Reviewers: Day AS, Vivas S S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Earlam E. Clinical tests of oseophageal function. BMJ. 1976;1080-1081 Available from: http//www.bmj.com/content/1/6017/1080.1. |

| 2. | Lim SB, Choi DH, Lee MS, Kim JH, Cho SW, Sim CS. A case of spontaneously passed long esophageal stent without any symptom. Kor J Gastroenterol. 1990;22:404 Available from: http://www.e-ce.org/journal/Archive.php. |

| 3. | Schwartz GF, Polsky HS. Ingested foreign bodies of the gastrointestinal tract. Am Surg. 1976;42:236-238. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Mcpherson RC, Karlan M, Williams RD. Foreign body perforation of the intestinal tract. Am J Surg. 1957;94:564-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Maleki M, Evans WE. Foreign-body perforation of the intestinal tract. Report of 12 cases and review of the literature. Arch Surg. 1970;101:475-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chao HH, Chao TC. Perforation of the duodenum by an ingested toothbrush. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4410-4412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Exner A. Wie schuetzt sich der verdanungstract ver verletzungen durch spitze fremdkoerper. Arch F D Ges Physiol. 1902;89:253. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Goh BK, Chow PK, Quah HM, Ong HS, Eu KW, Ooi LL, Wong WK. Perforation of the gastrointestinal tract secondary to ingestion of foreign bodies. World J Surg. 2006;30:372-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bundred NJ, Blackie RA, Kingsnorth AN, Eremin O. Hidden dangers of sliced bread. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;288:1723-1724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sutton G. Hidden dangers of sliced bread. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;288:1995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rivron RP, Jones DR. A hazard of modern life. Lancet. 1983;2:334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim HE. Characteristics of esophageal foreign bodies: thorns of Chromis notata. Kor J Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;35:231 Available from: http://www.e-ce.org/journal/Archive.php. |

| 13. | Webb WA. Management of foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract: update. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:39-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Coulier B. [Diagnostic ultrasonography of perforating foreign bodies of the digestive tract]. J Belge Radiol. 1997;80:1-5. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Goh BK, Tan YM, Lin SE, Chow PK, Cheah FK, Ooi LL, Wong WK. CT in the preoperative diagnosis of fish bone perforation of the gastrointestinal tract. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:710-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ngan JH, Fok PJ, Lai EC, Branicki FJ, Wong J. A prospective study on fish bone ingestion. Experience of 358 patients. Ann Surg. 1990;211:459-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |