Since the 1980s, the panorama of pancreatic resections has widened, with the development of new operations other than proximal and distal pancreatectomy (DP). The aims of these operations have been to spare normal pancreatic parenchyma. These new operations are duodenum-sparing pancreas head resection[1], resection of ventral or uncinate process of the pancreas[2], dorsal pancreatectomy[3], middle preserving pancreatectomy[4] and central pancreatectomy (CP)[5].

Although CP has gained its place in the clinical armamentarium of surgeons worldwide, many authors have reported incorrect information regarding the history of this operation, and subsequent authors have perpetuated this misinformation, because they not have carefully read and considered the original papers and have simply repeated the same wrong information without verification. This has been confirmed in our systematic review and meta-analysis of the papers published in English literature[6,7].

The aim of this report was to clarify the history of this technique in an attempt to avoid the emergence and perpetuation of inaccuracies about the origin and development of the procedure.

Data sources

Reviewing all the papers for a systematic review and meta-analysis, published on British Journal of Surgery 2013; 100: 873-885[7], we found out that most of the authors reported wrong information or believed to have discovered the technique.

Credit for the first description of segmental pancreatic resection must be given to Oskar Ehrhardt of the Elisabeth-Krankenhaus in Konigsberg, Prussia who published in 1908 on Dtsch med Wochenschr[8]. Finney[9] describes the operation performed by Ehrhardt in 1907 as follows: “Woman age 32 years; three months previously a gastroenterostomy had been performed for cancer of the pylorus. Operation showed cancer of pylorus and a separate tumor in head of pancreas. Stomach and upper portion of duodenum together with most of head and body of pancreas resected including duct of Wirsung. The two extreme ends of pancreas were left. These were then brought together by sutures and drained with gauze strips. Pancreatic fistula resulted. After two weeks piece of necrotic pancreas discharged through wound after which fistula closed”. In the original paper in German, Ehrhardt described that at 4 mo from the operation the patient suffered of local unresectable tumor recurrence and died after 1 mo from the diagnosis of recurrence. The original description in German reporting two cases reads[8]: “Der erste Fall betraf eine 32 jährige Frau mit einem seit etwa einem halben Jahr bestehenden Pyloruscarcinom. Im Mai 1907 fand sich bei der Laparotomie ein überfaustgroßes Carcinom des Pylorus. im Pankreaskopf fühlte man einen zweiten Tumor [ich führte] die Gastroenterostomia retrocolica post. [durch]. Am 4. August 1907 machte ich die Relaparotomie... man musste zunächst den Magen resezieren [ich] musste die Resektion am Duodenum bis in den absteigenden Teil fortsetzen. Ich nahm noch große Stücke des Pankreas fort. In der Tiefe dieses Defekts war ein Gang, der Ductus Wirsungianus eröffnet. Ich beschloss die Wundränder im Pankreas aneinander zu nähen, und hatte die Freude, dass ich wenigstens die Gegend des Ductus Wirsungianus adaptieren und so eine Art von Naht des Ganges machen konnt Ich legte einen Vioformgazestreifen in die Pankreaswunde. Der zweite Wundverlauf war ein guter, doch blieb an der Tamponstelle eine Fistel, aus der sich nach zwei Wochen ein ziemlich großer Sequester des Pankreas ausstieß. Hiernach verheilte die Fistel.

Dieser güntige Zustand hielt indessen nur 4 Monate an, im Dezember kam Patientin miteinem großen,inoperabeln Rezidiv zumir. Es handelte sich um ein großs Drüsenrezidiv, an dem Patientin 5 Monate nach der Resektion zugrunde ging.

Im zweiten fall, den ich nur kurz schildern will, da hier die Resektion des Pankreas wenig ausgedehnt war, handelte es sich gleichfalls um ein Pyloruscarcinom. Auch hier war der Tumor mit dem Pankreaskopf verwachsen. [Ich] konnte ihn im Pankreas abtrennen ohne mit den Arterien oder dem Ausführungsgang in Collision zu kommen. Ich nähte die Drüsenkapsel. über dem Defekt zusammen und schloß die Bauchwunde ohne zu tamponieren. Ich habe von der Patientin noch 1 ½ Jahre nach der Operation günstige Nachrichten gehabt.”

Finney[9] (Figure 1) in 1910 described segmental pancreatic neck resection for a cystic tumour. The two stumps were oversewn and not drained enterically and, as expected, the patient developed a pancreatic fistula. The reported description of the operation reads[9]. “The tumor would not shell out, and the whole middle portion of the gland was removed with it, leaving a small area each of the head and tail. These two fragments were brought together with mattress sutures of catgut. The patient bore the operation well. A fistula developed at the site of the drain which continued for about three months. Three times, including our own case, the gland has been completely divided and then the remaining portions brought together and sutured. All three cases recovered’’.

Figure 1 Dr.

JMT Finney (courtesy of National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health Department of Health and Human Services Bethesda, MD, United States).

For his time, Finney, first president of the American College of Surgeons[10], described a unique operation, however reconstruction was made by suturing together the two stumps. Suturing together two pancreatic stumps is not currently considered appropriate. Nonetheless it has been reported recently with anecdotal success in three patients (one with mucinous cystadenoma and two with traumatic transection of the pancreatic neck)[11] and in experimental mongrel dog model[12] with an end-to-end anastomosis between the two pancreatic stumps, and with pancreatic duct anastomosis (duct-to-duct) with or without stenting.

Takada et al[13] ascribed the first CP operation to the work done by Honjyo in 1950[14]. This paper which was published in Japanese, and unfortunately, for which translation has been not available until now in literature, described two cases of central resection of the pancreas combined with gastrectomy for gastric cancer infiltrating the neck of the pancreas. Although Honjyo did a central resection, the distal pancreatic stump was not reconstructed. Instead it was oversewn and wrapped with omentum in attempt to prevent pancreatic leakage. The proximal stump was also oversewn.

The primary closure of distal pancreatic stumps without entero-pancreatic anastomosis is currently not considered appropriate. Nonetheless primary closure of the distal stump was recently reported, surprisingly, without any pancreatic fistulation[15].

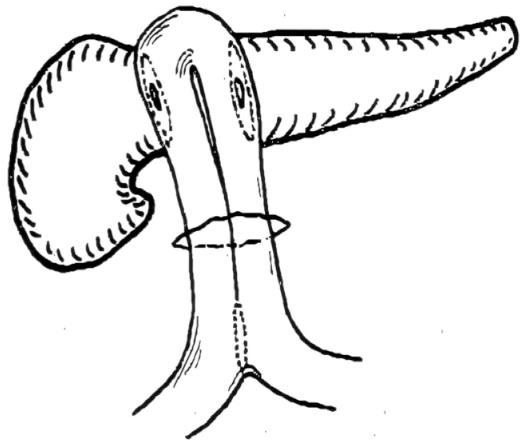

Guillemin and Bessot[16] in 1957 or Letton and Wilson[17] in 1959 suggested by some authors as first Authors to introduce CP, described only the reconstructive aspect of CP. In fact Guillemin and Bessot[16] only carried out transection of the isthmus followed by a double digestive anastomosis of the two pancreatic stumps to an omega-shaped jejunal loop (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Technique performed by Guillemin and Bessot to reconstruct an accidental pancreatic transection while searching for the Wirsung duct for intraoperative wirsungraphy (published in Mem Acad Chir Paris; 83: 869-871, with permission of Mem Acad Chir Paris).

Guillemin and Bessot[16] treated a patient with calcifying chronic pancreatitis and renal tuberculosis. In an attempt to visualize the main pancreatic duct, they inadvertently transected the entire pancreatic neck and decided to drain the two pancreatic stumps with an omega jejunal loop.

The original description of their operation (in French) reads. “Intervention le 27 mars 1957: le pancreas volumineux est induré, rigide, sur toute son étendue, On s’efforce de découvrir par punction le canal de Wirsung, puis de pratiquer une pancréatographie. On ne recuille pas de liquide, et les clichés ne son pas concluanis. l’incision du pancreas a la jonction de la tete avec l’isthme ne permet pas de trouver le Wirsung. On arrive ainsi sur le confluence portal. Devant cette situation, aprés avoir realize une sectione transversale complete du pancreas on prend la decision de faire une double anastomose du sommet de l’anse jéjunale avec chacune des tranches de section pancréatique. Anastomose pancréato-jéjunale en deux plans aux points séparés, solidarisation par quelques points des branches afférente et efferente de l’anse jéjunale qui est amarrée au mésocolon tranverse, anastomose latéro-latérale jéjuno-jéjunale au pied de l’anse[16]”.

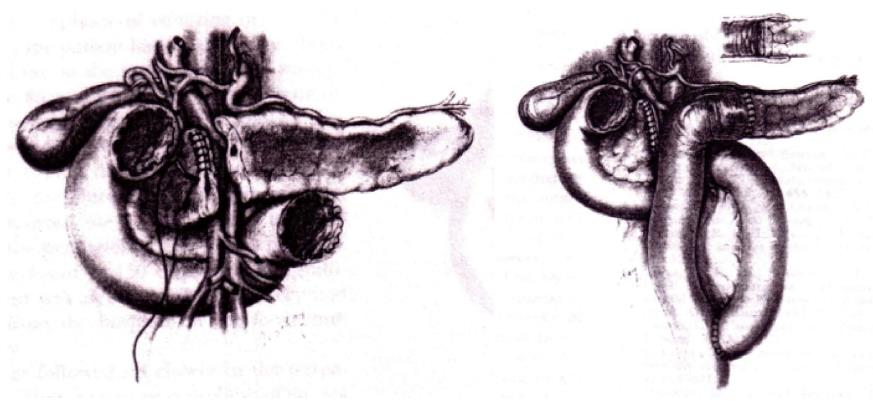

Letton and Wilson[17] performed the reconstructive aspect of CP by oversewing the cephalic stump with interrupted sutures and carrying out a pancreatico-jejunostomy to the distal stump. However this reconstruction was performed in a patient with traumatic transection of the neck of the pancreas, although no pancreatic parenchymal resection was performed (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Drawing of reconstruction after pancreatic traumatic transection of the pancreatic neck using by Letton and Wilson (published on Surg Gynecol Obstet 109: 473-478, with permission of Elsevier Science Inc.

United States).

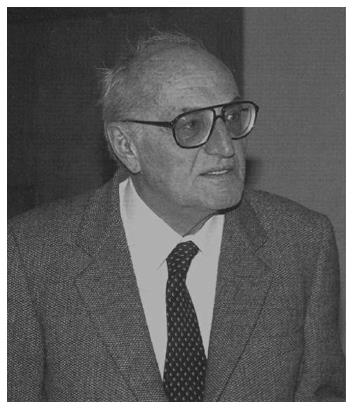

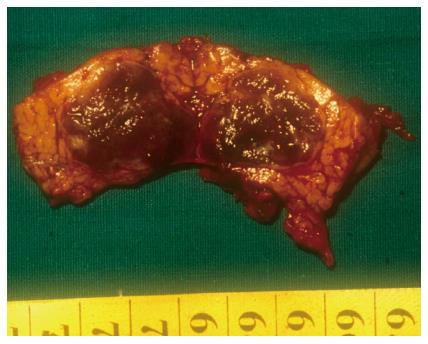

In 1982, Dagradi (Figure 4) and Serio planned and performed the first CP to resect an insulinoma of the pancreatic neck (Figure 5); they reported the technique in 1984 in Enciclopedia Medica Italiana (Figure 6)[5].

Figure 4 Professor Adamo Dagradi, a pioneer in hepato-biliary-pancreatic surgery (from the book: Scritti in onore di Adamo Dagradi nel XXV anniversario del suo ordinariato, Grafiche Fiorini, Verona 1989 with permission).

Figure 5 Surgical specimen from the first central pancreatectomy operation to resect an insulinoma of the pancreatic neck (published in J Gastrointest Surg 11: 364-376 with permission of Springer, New York, United States).

Figure 6 Surgical technique of central pancreatectomy reported in 1984 in Enciclopedia Medica Italiana (with permission of UTET Scienze Mediche, Torino, Italy).

To spare normal pancreatic parenchyma, Dagradi and Serio removed an insulinoma from the pancreatic neck by CP. This landmark operation in 1982 marked the first use of CP. These Authors described the resective and reconstructive aspects of the technique.

The original technique included the following steps. After incision of the superior and inferior margins of the pancreas the segment harbouring the lesion was mobilized, and the pancreas was isolated at its superior margin from the splenic artery, ligating and severing some collateral vessels. Subsequently the posterior surface of the pancreas was carefully dissected from the splenic vein in such a way as to avoid vessel injury. After placing marginal stitches on the cephalic and distal sides, the pancreas was transected. The resected pancreatic specimen was sent for pathological analysis to check the resection margins and to confirm the diagnosis by frozen sections. Haemostasis of the two raw surfaces was achieved with 4 or 5/0 stitches. Wirsung’s duct of the cephalic stump was sutured selectively with a figure-of-eight stitch. A row of 3/0 non-absorbable interrupted overlapping stitches of the mattress type was along the entire length of the stump and tied. An end-to-end pancreatico-jejunostomy was carried out with a single layer of 3/0 non-absorbable interrupted stitches. The operation was concluded with the construction of an end-to-side jejuno-jejunostomy with a double layer of absorbable stitches, approximately 50 cm distal to the pancreatic anastomosis.

Subsequently Serio and Iacono[18-35] have validated and popularized this technique, with several reports in the national and international literature as well as several congress presentations and videos with the appropriate indications and contraindications.

In these papers the indications for CP were: benign lesions between 2 and 5 cm in size, where a simple enucleation entails risk of injury to the main pancreatic duct; cystic lesions not suitable for enucleation especially in young patients; symptomatic serous cystadenoma; mucinous cystadenoma; pseudopapillary tumours; small tumours that are deeply located in the gland and are therefore not eligible for simple enucleation; focal chronic pancreatitis with isolated and short stenosis of Wirsung’s duct; solitary metastases in the pancreatic neck, for example, from kidney, and metastatic pancreatic endocrine tumours in a multimodality program treatment; and selected cases of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN).

The contraindications of this technique were: malignant tumours (especially ductal adenocarcinoma); neoplastic involvement from other organs (e.g., stomach, or colon); diffuse chronic pancreatitis; large lesions for which it is not possible to preserve at least 5 cm of distal pancreatic stump; distal body-tail atrophy; and Mellière and Moullé type-III pancreatic vascularisation (the body-tail of the pancreas receives its arterial blood supply exclusively from the transverse pancreatic artery, left branch of the dorsal pancreatic artery)[36].

At the end of the 1980s, this technique aroused criticism owing to the high risk for the formation of fistula because of the presence of two pancreatic stumps.

In 1988, the French surgeon Fagniez reported two cases of limited conservative pancreatectomy[37]. Thereafter Asanuma et al[38] reported other two cases of segmental pancreatectomy in 1993, and in the same year Rotman et al[39] of Fagniez group, reported 14 cases of medial pancreatectomy.

This operation initially named intermediate pancreatectomy, in 1994 it was renamed as CP[24]. In 1995, the results on 11 patients were presented at Annual Meeting of Pancreas Club Inc. in San Diego by Iacono. Ikeda et al[40] published their results with 24 cases, and Fernandez-Cruz and colleagues described three cases (treated with what they called conservative pancreatic resection)[41].

Many different terms to define the same operation appears a way to rediscover an already known technique. Among the different denominations the term CP seem to be the most appropriate and nowadays it it the most frequently used in the literature. The other terms that can be currently found are middle pancreatectomy, median pancreatectomy, medial pancreatectomy, segmental pancreatectomy, limited conservative pancreatectomy, intermediate pancreatectomy.

In 1997 we assessed the functional results after CP with oral glucose tolerance test, the pancreo-lauryl test, and assay of faecal fat excretion in all of the operated patients; moreover in a subgroup of patients the same tests were been performed before and after surgery[42]. Our results showed that there was no postoperative impairment of endocrine and exocrine function.

In 1998, Warshaw at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston applied this technique for the first time in United States and described it in a paper entitled “Middle segment pancreatectomy: a novel technique for conserving pancreatic tissue”[43].

In 1998, Partensky et al[44] reported the first 10 cases of reconstruction of the distal stump with pancreatico-gastrostomy. Currently, many pancreatic groups perform CP worldwide[7,45-55].

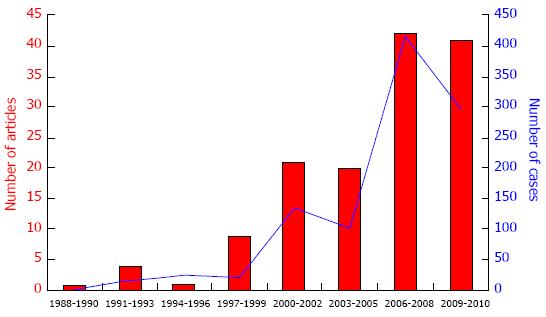

By the end of the 1990s, the number of publications about CP had increased and to 2010, about 1000 cases have been reported[6,7] (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Trend of publications and number of cases of central pancreatectomy from 1988 to 2010.

More recently, in 2003, Baca and Bokan[56] performed the first laparoscopic CP for a case of cystadenoma in a 55-year-old woman. Their full-text original paper was published only in German, while in English was published only the abstract in which they reported the following description: “The patient was placed in lithotomy position. Four trocars were placed the pancreas showed a 6-cm × 6-cm × 6-cm, well-bordered, cystic tumor in the corpus. The healthy tissue in the head area of the pancreas was divided with the linear stapler. The resected pancreas segment was placed in an endobag until removal. The tail segment was anastomized in situ end-to-side with the first jejunum loop behind the Treitz’s ligament. There was no postoperative complication, and the postoperative course was observed...”.

Other authors have described cases managed with a laparoscopic approach[7,57-60]. In 2004, Giulianotti et al[61,62] performed the first robot-assisted CP. Since then, other have also undertaken robot-assisted CP[7,62-65]. The description of the operation from the paper of Giulianotti et al[62] was: ‘‘a 12-mm trocar was placed in order to position a 30-degree-scope robotic camera at the umbilicus. Three 8-mm robotic ports were inserted. An additional 12-mm port was placed on the left side of the umbilicus for use with the assistant’s instruments. The first part of the procedure was performed laparoscopically. The gastrocolic ligament was opened. An ultrasonic examination of the pancreas was performed. The da Vinci surgical arm cart was then brought into a position directly cranial to the patient and docked to the robotic trocars. The splenic artery on the superior border of the pancreas was dissected and surrounded with a vessel loop. The superior mesenteric vein was exposed at the inferior edge of the pancreatic neck. Using the robotic grasper, a tunnel was created under the pancreatic neck. Upon completion of the tunnel, tape was passed through, which was divided to the right side of the lesions by using an endoscopic stapler. Interrupted stitches of polypropylene 4/0 were applied to the proximal stump. The pancreatic body was progressively dissected from the splenic vessels. Each small branch of the splenic vein and artery, to and from the pancreas, was tied and sectioned. Transection of the pancreas was carried out on the left side of the lesions, using a robotic ultracision device. The anterior wall of the distal pancreatic remnant was then anastomosed to the posterior wall of the gastric body, using a single layer of monofilament 4-0 running suture. The gastric wall was and the posterior aspect of the pancreatic stump was sutured to the posterior gastric wall by using a single layer of monofilament 4-0 running suture. Interrupted 4-0 polypropylene stitches were placed to reinforce the pancreaticogastrostomy and to achieve hemostasis of the eventual bleeding point. Two drains were systematically’’.

In the systematic review, recently published, in 963 CP operations performed before the end of 2010 a complication rate of 45.3% and a mortality rate of 0.8% were reported. The incidence of exocrine and endocrine insufficiency was very low. The most frequent indications for CP were endocrine tumours followed by cystic tumours[66].

From a technical perspective the most frequent reconstruction for the distal stump was pancreatico-jejunostomy followed by pancreatico-gastrostomy. On the other hand, the proximal stump is treated in many cases by burying it with interrupted stitches after elective closure of Wirsung’s duct[6,7].

Some recent papers have compared CP with DP. A meta-analysis confirmed that the exocrine and endocrine functions are well preserved following CP compared to DP despite a higher incidence of complications associated with CP than DP[6,7].