LITERATURE RESEARCH

A systemic review of the scientific literature was carried out using PubMed - Medline, Embase, the Chochrane library and Clinical trials gov., and relevant online journals and the internet for the years 1983 - February 2014 to obtain access to all relevant publications, especially randomized controlled trials, systemic reviews and metaanalysis involving neuroendocrine tumors and laparoscopic surgery. The search terms were: NET, Enets, neuroendocrine tumor, globelet cell tumor, carcinoid, laparoscopy, laparoscopic surgery, mis, mic, laparoscopic colectomy, laparoscopic colorectal surgery, colectomy, appendectomy, laparoscopic appendectomy, meckel diverticulum and small bowel.

HISTOLOGY, STAGING, GRADING AND PROGNOSIS ASSESSMENT

The histopathological routine diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors based on an assessment by the WHO classification and the additional consideration of the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society ENETS consensus proposal[7,8].

According to the ENETS recommendations[9], the implementation of immunohistochemistry with synaptophysin and chromogranin A (CgA) as a basic diagnostics is proposed to confirm the diagnosis of a neuroendocrine tumor and additionally an immunohistochemistry with MIB-1 (Ki-67 antigen) should be performed to determine the proliferation fraction as standard of care.

In the current WHO classification the GEP-NETs are classified according to the particular localization of the primary tumor, since their tumor biology, metastasis and prognosis differ significantly depending on the primary location of the tumor. The old and the new WHO classifications distinguish between well-differentiated and poorly differentiated neoplasms. All well-differentiated neoplasms, regardless of whether they behave benignly or develop metastases, will be called NETs, and graded G1 (Ki67 < 2%) or G2 (Ki67 2%-20%). All poorly differentiated neoplasms will be termed neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) and graded G3 (Ki67 > 20%)[2,10]. To stratify the GEP-NETs and GEP-NECs regarding their prognosis, and thus also for the differentiated treatment decision and deciding on the appropriate aftercare or follow-up, they are now further classified according to TNM-stage systems that were recently proposed by ENETS and the AJCC/UICC[10].

TUMOR MARKERS IN NET

CgA is recommended for all known NETs of the GEP tract[11]. The determination of CgA has for all NETs of the GEP a sensitivity of 56%-85% and a specificity of 64%-96%. Various assays differ in sensitivity and specificity and are therefore not directly comparable. Moderate increases in serum levels of CgA can the differential diagnosis by the following diseases be caused; medication with proton pump inhibitors, ECL hyperplasia of the stomach with hypergastrinemia in chronic atrophic gastritis (NETs of the stomach type 1), primary hyperparathyroidism, pituitary adenomas, pheochromocytoma, neuroblastoma, C-cell hyperplasia of the thyroid gland, medullary thyroid carcinoma, essential arterial hypertension, heart failure, kidney failure or liver failure. From a determination of CgA as a pure screening parameter for tumor search is therefore not recommended.

GENETIC TESTING IN NET

The indication for genetic counseling and genetic diagnosis must be considered and the differential diagnosis with NET of the pancreas, since they not only sporadically, but can occur in the context of hereditary syndromes of the following in about 5%-10% of all cases[1]; Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) - the syndrome includes primary hyperparathyroidism, NET of the pancreas (gastrinomas, insulinomas, non-functional), Hypophysendadenome, rarely thymic or bronchial NET, Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) syndrome including pheochromocytoma, hemangioblastoma of the CNS, renal cell carcinoma and retinal angioma, cysts and serous cystadenomas of the pancreas. In almost 10% of all patients with VHL syndrome functionally inactive NETs of the pancreas additionally occur.

NUCLEAR MEDICINE IMAGING

Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS) using 111In-DTPA octreotide (OctreoScan®) including additional SPECT imaging is a widely available and sensitive means of detecting SSTR-positive tumors[12]. Recently, PET-computed tomography (PET-CT) using 68gallium-labeled compounds was introduced for diagnosis of these tumors[12]. This imaging method has been shown to be superior to SPECT and CT for various indications, i.e., initial diagnosis, staging and restaging.

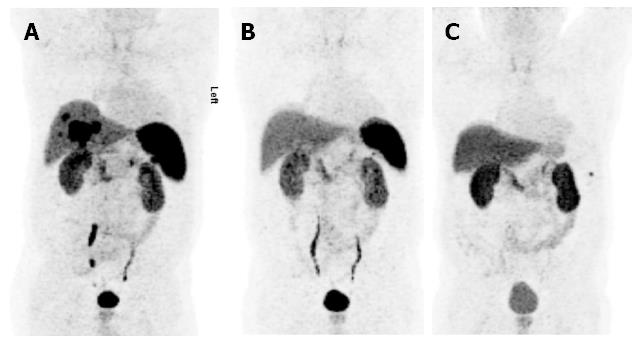

This cross-sectional imaging method using 68gallium-labeled compounds is characterized by excellent spatial resolution and pharmacokinetic properties. This investigation can be performed within a few hours after tracer administration and has a significantly higher detection rate, catching even small lymph nodes and bone metastases, while conventional 111In-pentetreotide scintigraphy requires one to two days for performance and has lower sensitivity. Unexpected distant metastases that would have escaped the usual diagnostic procedures are also identified by 68Ga-PET scan[12]. In such situations, in particular in progressive disease, systemic therapy approaches are inevitable. However, tumor burden reduction should be considered in any stage, even in metastatic disease, and thus an accurate staging procedure is required for management of these patients. A very important advantage of this tracer over other PET tracers is the ability to also assesses the SSTR status of lesions derived from the NET, which is necessary for administration of radiolabeled SST analogs for therapeutic use[13]. Meanwhile, various compounds are available including 68Ga-DOTA-[Tyr3] octreotate (Ga-DOTA-TATE), 68Ga-DOTA-[Tyr3] octreotide (Ga-DOTA-TOC) and Ga-DOTA-NOC[13] as shown in Figure 1. By contrast, 18F-FDG, commonly used in oncology, is of minor importance in these tumors, mostly due to their low metabolic activity. Only in poorly differentiated carcinomas of neuroendocrine origin can the use of this tracer be considered[14]. All these nuclear medicine imaging techniques are applied to properly characterize tumor lesions in terms of inherent biological features and extent of disease.

Figure 1 Various compounds.

68Ga-DOTA-NOC-PET was performed in a 68-year-old patient with metastatic insulinoma of the pancreatic tail; initial presentation with multiple liver metastases (A) that largely disappeared after three applications of 90Y-DOTA-TOC (13 GBq overall activity). Follow-up after the last PRRT clearly revealed improvement of the extent of disease (B). The patient subsequently underwent laparoscopic resection of the pancreatic tail, of one liver segment and splenectomy. PET reevaluation after 1.5 years showed no residual disease (C).

Based on ionizing radiation image-guided approaches using radiolabeled SST analogs are under investigation to improve intraoperative detection of small lesions using gamma probes[15]. Such promising techniques, however, require further confirmation and standardization in clinical trials. Initially, it was shown in nine patients with suspected GEP-NET that intraoperative gamma counting localized three carcinoids and additionally revealed lymph node metastases in one case[16]. Radio-guided surgery depicted five pancreatic NETs, the smallest of which was 8 mm in diameter. This technique may become an ideal supplement to laparoscopic procedures.

SURGICAL STRATEGIES ACCORDING TO NET SITE

NETs of the gastrointestinal tract are classified as tumors of the stomach, duodenum, small bowel, appendix, colon or rectum.

Gastric NETs

These account for approximately 7% of all NETs are divided into three different types: Type 1 associated with chronic atrophic gastritis, type 2 associated with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, and a sporadic type 3[17]. Most of them, estimated 70%-80%, are type 1 and-non aggressive. However, the typical appearance is in multiple lesions[18]. Treatment is dependent on tumor size, depth of infiltration and gastrin dependency, as well as the presence of metastasis. Standard treatment of type 1 lesions < 1 cm is endoscopic removal and observation. Lesions > 1 cm should be further staged by endoultrasound followed by endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR).

Surgery is recommended if the tumor spreads beyond the submucosa or if R0 was not achieved with EMR. In such cases antrectomy or distal gastrectomy is mandatory. Depending on the tumor site, total gastrectomy can be the only treatment option[18].

Role of laparoscopy: Very little literature is available on the laparoscopic treatment of gastric NET. However, there is evidence to show that laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with or without lymph node dissection for cancer is safe and has all the advantages of laparoscopy as compared to open resection[19,20]. In difficultly situated lesions and/or small submucosal lesions that are too big for EMR but feasible for a wedge resection, a rendezvous technique appears to be easy and safe. A combination of endoscopy and laparoscopy might help localize the tumor for laparoscopy and minimize the percentage of resected stomach[21]. This technique was successfully described in 1999[22] and in modern set-ups today is known as a hybrid NOTES procedure[23]. In summary, laparoscopic resection of gastric NETs is feasible and safe, while providing shorter hospital stay and improved quality of life. From an oncological point of view, it is equivalent to open resection[24].

Duodenal NETs

These tumors make up only 5% of all NETs of the gastrointestinal tract. They have a low rate of distant metastasis (9%-15%)[25] and therefore an excellent prognosis and a high postoperative survival rate of 83.3%[26]. For preoperative localization diagnosis of sometimes very small tumors in the pancreas/duodenal wall, PET-CT showed high sensitivity in delineating malignant lesions[27]. For small lesions < 1 cm endoscopic resection should be the treatment of choice. In the periampullary region transduodenal resection might be favorable to endoscopic resection. However, there is no standard or consensus for tumors between 1 and 2 cm[28]. A minimally invasive rendez-vouz procedure combining endoscopy and laparoscopy like in gastric surgery might also be a promising way to treat such lesions[29,30]. A radical resection should always be considered, at least for tumors > 2 cm[31], even in cases involving known distant metastases with impact on further prognosis[32,33]. This usually calls for a duodenopancreatectomy (Whipple procedure) or a pylorus-preserving duodenopancreatectomy. At specialized centers 5-year survival rates exceeding 60% can be achieved after R0 resections, independently of the extent of surgery, with surgical mortality below 5% and acceptable morbidity ranging between 20% and 30%[32].

The role of laparoscopy is limited. In his review Gagner reported 146 laparoscopic Whipple procedures performed from 1994 to 2009 for different indications. The reported procedures are different, mixing laparoscopic with laparoscopically assisted and manually assisted. The conversion rate was 46%[34]. However, a total laparoscopic Whipple procedure is feasible[35]. The most recent review shows that experienced and specialized centers can perform a duodenopancreatectomy laparoscopically with a reasonable operating time and low morbidity and mortality[36]. Still, it is not yet standard.

In summary, laparoscopy for duodenal NETs is beneficial in hybrid NOTES technique for full-thickness resection of a limited lesion. Laparoscopic duodenopanreatectomy is feasible.

NET of the pancreas

Functionally inactive NET of the pancreas account for up to 85% of NET of the pancreas. These tumors are often large at diagnosis, as they are diagnosed only by local displacement phenomena or random. The task of imaging procedures is the differential diagnostic distinction of functionally non active NETs of the pancreas from pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Here FDG uptake pattern in PET/CT can differentiate malignant from benign mass-forming lesions of the pancreas with high accuracy[37]. Due to improved diagnosis, the incidence of non-functional neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors has increased significantly in recent years. A radical resection should always be sought, at least for tumors > 2 cm[31]. Both an R1 resection including vascular grafts in large NET of the pancreas, as well as operations of the first violinist in already with distant stage seem to impact favorably on the prognosis and should be considered to surgical pancreatic centers[38]. Overall 5-year survival rates of > 60% may be achieved at R0 resections, regardless of the scale of operation leading to surgical mortality rates below 5% and acceptable morbidity between 20% and 30%[32].

Laparoscopic surgery has been established as feasible and safe for distal pancreatectomy. The technique has been accepted in the treatment of solitary and small Nets. Michelle Gagner is known as a pioneer in minimally invasive surgery of pancreatic nets and was one of the first surgeons describing minimally invasive surgery for nets on the pancreas in 1996[39]. Several case series have been published demonstrating the feasibility of laparoscopic resection of neuroendocrine tumors in the pancreas[40]. Fernandez - Cruz showed in 49 patients, that the oncological criteria may be achieved without any difference to the open approach and patients benefit due to the short hospital stay and low morbidity[39]. Lo could show that tumors can be enucleated from the body of the pancreas or treated by resection of the tail safely[41]. Intraoperative ultrasound may seem to be useful and sensitive for the localization[42]. However there is a lack of randomized trials.

Small bowel NETs

Forty percent of all gastrointestinal NETs are found in the distal jejunum and ileum, most commonly in the terminal ileum. Of these so-called mid-gut tumors 25%-30% contain multiple tumor lesions. If tumors are smaller than 1 cm, the probability of lymph node involvement is less than 5%. However, malignant lesions in this region are usually larger than 1 cm with invasion of the muscularis propria. In this situation NETs are often already metastasized. A carcinoid syndrome is generally observed in only about 5%-10% of NETs. It mainly occurs in mid-gut tumors of the ileum or jejunum with liver metastasis, sometimes accompanied by endocardial fibrosis of the right heart and bronchospasm.

Small-bowel carcinoids often also induce local obstruction of the bowel by desmoplastic reaction of the adjacent mesenteric connective tissue with the clinical feature of an ileus. Thus, surgical resection of the primary tumor is the most important treatment option[43], even in a palliative situation with known distant metastases, and results in overall better outcome. A recent study showed better results with improved survival in patients with unresectable liver metastasis[44]. It should be noted that even primary tumors < 1 cm in diameter show a very high rate of lymph node metastases. Therefore, for proven or suspected small-bowel NET central lymph node dissection should always be performed. Moreover, it is recommended that a prophylactic cholecystectomy also be performed in well-differentiated tumors as a possible systemic treatment approach after initial intervention in order to avoid possible side-effects from the administration of long-acting somatostatin analogs[45]. Since NETs of the small intestine are sometimes also associated with non-endocrine neoplasia of the gastrointestinal tract, postoperative endoscopic evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract is routinely recommended to exclude other malignancies and especially adenocarcinomas.

The available scientific literature rarely mentions the role of laparosocopy in treatment of small bowel NETs. However, for small lesions it is feasible to perform a laparoscopically assisted full-thickness endoscopic resection including lymph node dissection[30]. In all other cases, laparoscopy is suitable and safe for identification of the tumor and performance of a radical resection of the mass including a lymph node dissection. This is even more beneficial as the exact location of the tumor might not have been identified in the preoperative diagnostic work-up. With regard to locating the tumor, laparoscopy is at least as good as open surgery and will give the patient all the benefits of minimally invasive surgery as opposed to an open approach. Surgery should be performed by an experienced surgeon. Small lesions of the submucosa often present themselves only as a localized fibrosis or thickening of the intestinal wall[46]. However, in each case the whole small intestine has to be examined from the ligament of Treitz to the ileocolic valve. In asymptomatic patients or if the mass is found accidentally prophylactic resection of the tumor is recommended[47].

A rare NET site in the small bowel is the coincidence of a Meckel diverticulum gathering the tumor. A review published in 2000 reported 111 cases. This NET location is an ideal indication for laparoscopy. The tumor can be resected with a single cut using an endoscopic stapling device[48]. The technique is similar to a laparosocpic appendectomy. Alternatively, it can be performed by segmental resection including intracorporeal stapled or sewn anastomosis. Another safe way is to perform a minilaparotomy at the site of a trocar (e.g., at the umbilicus or suprapubic area), bring out the mass and perform an open resection.

Appendix NETs

Neuroendocrine tumors of the appendix are most often found accidentally during an appendectomy for suspected acute appendicitis. NET may also be revealed in a normal-looking appendix removed during gynecological laparoscopy[49]. The incidence of NET in histological examination following appendectomy is 0.3%-1.1%[50]. These tumors are rare and rarely associated with typical carcinoid symptoms[51]. The prognosis is usually good because of the typical location at the tip of the appendix[1]. No randomized trial has been conducted on the value of laparoscopy in the treatment of NETs of the appendix. Bucher found in his retrospective analysis comparing patients undergoing open or laparoscopic appendectomy (LAE) for NET that LAE is safe and equivalent to open appendectomy. The authors conclude that the preoperative diagnosis of appendiceal NET is not a contraindication for LAE[52]. The main questions posed by the tumor site are if, when and how to perform a re- operation. Tumor size > 2 cm, infiltration of the mesoappendix and histologically proven globlet cell carcinoid should be followed by oncologic right-sided hemicolectomy[53] or ileocecal resection including the ileocecal vessels[54]. If the mesoappendix is infiltrated, the risk for distant metastasis increases to almost 50%. Evaluation of the mesoappendix and the meso of the ileocecal region can be easily performed laparoscopically. This gives rise to the general opinion that laparoscopy is beneficial in patients with suspected appendiceal mass. However, there is very little evidence to prove this point. The first case report on a laparoscopic two-stage resection of a globlet cell carcinoma was made in 2006[55], followed by a case report on the same topic in 2008[56]. Both authors conclude that there is very little evidence to support laparoscopy for NET, but that laparoscopy should be seen to have the same value as for appendix tumors of other entities. Therefore, laparoscopic treatment provides the same results as does open surgery[53]. Finally, a recently published case report including a review of the literature presents the first case involving the 2010 WHO diagnostic criteria[57].

NETs of the colon are normally characterized by poor prognosis; most of these tumors show distant metastases at the time of initial diagnosis. Colonic NETs should be staged according to the TNM Classification, as suggested by Rindi et al[8]. Tumors > 2 cm are treated by colon resection including local lymph node dissection according to the tumor site similar to colon cancer. While there is neither specific evidence and nor randomized trials comparing open and laparoscopic treatment of colonic NETs, there is enough indeed evidence with regard to laparoscopic surgery and colon cancer. Two questions are of interest here: is it oncologically safe to remove a colonic tumor laparoscopically or not. Abraham in 2004 published short-term outcomes following laparoscopic resection for colon cancer. Laparoscopy is associated with less morbidity, less pain, faster recovery and shorter hospital stay than is open resection, without compromising oncological clearance[58]. Bonjer summarized the available data in his review including 12 randomized trials with long-term data; these studies included 3346 patients. Bonjer concluded that laparoscopic surgery for colon cancer is safe and provides the same oncologic results as open surgery[59]. NETs of the rectum are relatively common and usually detected by endoscopy as small submucosal, highly differentiated tumors. Rectal NETs < 1 cm with no infiltration of the muscularis propria have excellent prognosis. However, only two-thirds of tumors are smaller than 1 cm at diagnosis. In the presence of rectal NETs endosonography is recommended to estimate tumor size, depth of tumor invasion and evaluate perirectal lymph nodes. Moreover, an MRI investigation with rectal filling is useful to assess local invasion of the primary tumor and the extent of lymph node involvement. Very low-risk tumors < 1 cm with invasion of the submucosa only (T1A N0 M0) can be removed by endoscopic submucosal dissection or by transanal resection. Patients with G1 tumors and tumor-free margins can be considered cured after this procedure. The standard polypectomy with a snare is not recommended because of submucosal spreading and, consequently, incomplete removal.

Tumors of 1-2 cm in diameter have an intermediate risk of developing lymph node metastasis, which can be managed similarly to the very low-risk group provided that enosonography and MRI do not raise any suspicion of invasion of the muscularis mucosae and/or lymph node metastases.

Lesions > 2 cm in diameter with exclusion of distant metastases call for anterior resection of the rectum. The value of laparoscopy for this diagnosis is similar to that for rectal cancer. Breuink found in his Cochrane review that laparoscopy for rectal cancer provides less blood loss and fewer clinical advantages with regard to length of stay, pain and quality of life[60]. Recently, the Dutch group published their long-term results on laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer with regard to health-related quality of life (COLOR II). They found no difference after four weeks and up to 24 mo. This is the first trial to conclude that HRQL following rectal cancer surgery was not affected by surgical approach[61]. Since 2007 a novel approach has been described with regard to reduction of access trauma. Single-incision surgery for colon pathologies was first described by Remzi and is slowly evolving at highly specialized centers[62]. While a first review by Makino et al[63] demonstrated that this technique is feasible and safe for the colon, we do not know the real advantages of this reduced-port technique. This is also true for rectal cancer[64]: further trials are needed to prove the benefit of this approach.

SURGICAL AND LOCAL ABLATIVE THERAPY OF LIVER METASTASES

In the presence of resectable metastases of highly differentiated G1 and G2 neuroendocrine carcinomas resection can improve overall prognosis with even complete remission in individual patients, although tumor recurrence within five years can be assumed for the majority of patients. For palliative reasons resection may also be performed provided that more than 90% of the tumor mass can be safely resected in debulking surgery. Surgical treatment approaches can also be combined with local ablative strategies, such as radiofrequency ablation or laser ablation. This is especially indicated in the case of multiple liver metastases. Furthermore, radiofrequency ablation can also be an alternative to surgery in patients with higher risk for extensive surgery, namely as a means of omitting anesthesia.

Laparoscopic resection of selected liver metastases is feasible. The indication for laparoscopy depends on the lesion site. Only one non-randomized trial comparing open vs laparoscopic resection for neuroendocrine liver metastasis has been published. The authors conclude that laparoscopy is safe in select cases[65].