Published online Oct 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i39.14479

Revised: March 16, 2014

Accepted: June 20, 2014

Published online: October 21, 2014

Processing time: 344 Days and 2.5 Hours

AIM: To assess “top-down” treatment for deep remission of early moderate to severe Crohn’s disease (CD) by double balloon enteroscopy.

METHODS: Patients with early active moderate to severe ileocolonic CD received either infusion of infliximab 5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, 6, 14, 22 and 30 with azathioprine from week 6 onwards (Group I), or prednisone from week 0 as induction therapy with azathioprine from week 6 onwards (Group II). Endoscopic evaluation was performed at weeks 0, 30, 54 and 102 by double balloon enteroscopy. The primary endpoints were deep remission rates at weeks 30, 54 and 102. Secondary endpoints included the time to achieve clinical remission, clinical remission rates at weeks 2, 6, 14, 22, 30, 54 and 102, and improvement of Crohn’s Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity scores at weeks 30 and 54 relative to baseline. Intention-to-treat analyses of the endpoints were performed.

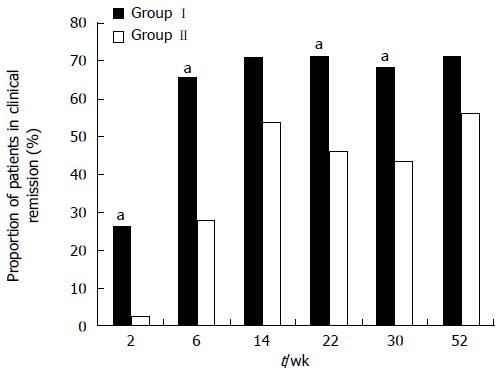

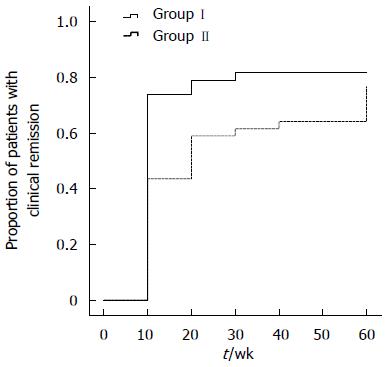

RESULTS: Seventy-seven patients were enrolled, with 38 in Group I and 39 in Group II. By week 30, deep remission rates were 44.7% and 17.9% in Groups I and II, respectively (P = 0.011). The median time to clinical remission was longer for patients in Group II (14.2 wk) than for patients in Group I (6.8 wk, P = 0.009). More patients in Group I were in clinical remission than in Group II at weeks 2, 6, 22 and 30 (2 wk: 26.3% vs 2.6%; 6 wk: 65.8% vs 28.2%; 22 wk: 71.1% vs 46.2%; 30 wk: 68.4% vs 43.6%, P < 0.05). The rates of clinical remission and deep remission were greater at weeks 54 and 102 in Group I, but the differences were insignificant.

CONCLUSION: Top-down treatment with infliximab and azathioprine, as compared with corticosteroid and azathioprine, results in higher rates of earlier deep remission in early CD.

Core tip: We assessed the outcome of “top-down” treatment in terms of deep remission in treatment-naïve patients with early Crohn’s disease (CD) with small bowel involvement. This study is believed to be the first designed with deep remission as the primary endpoint. Furthermore, mucosal healing was assessed by double balloon enteroscopy for the first time in patients with CD treated with biologic agents. We excluded patients with luminal fibrostenotic or abdominal fistulizing CD in screening, resulting in encouraging deep remission rates at week 30. These results may have implications in the treatment of CD.

- Citation: Fan R, Zhong J, Wang ZT, Li SY, Zhou J, Tang YH. Evaluation of “top-down” treatment of early Crohn’s disease by double balloon enteroscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(39): 14479-14487

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i39/14479.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i39.14479

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) comprises a heterogeneous group of conditions affecting the gastrointestinal tract; Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are the two main recognized entities. CD is a transmural inflammatory disorder that may involve various sites of the gastrointestinal tract, including the terminal ileum in 40%-70% of cases. Data from population-based cohort studies show that the majority of patients experience a progressive course that transits from pure inflammatory lesions to destructive complications such as stricture, fistula and abscess[1-3]. There are many reports indicating a change in behavior over time from a non-stricturing, non-penetrating type (disease complications absent) to stricturing and/or penetrating disease (disease complications present)[1,2,4-6]. These complications and the surgical resection for them can result in irreversible bowel damage that in turn leads to loss of gastrointestinal tract function and disability.

Changing the natural history and avoiding evolution to a disabling disease should be the main goal of treatment. Historically, induction and maintenance of clinical remission seemed insufficient to change the natural history of IBD. Mucosal healing (MH) as a therapeutic endpoint has recently become more widely incorporated into clinical trials, in addition to more traditional subjective clinical activity indices, because it has been shown to reduce the likelihood of clinical relapse, reduce the risk of future surgery, and reduce hospitalization. The concept of deep remission is a recently introduced endpoint, which includes clinical remission and MH. Several studies have indicated that corticosteroids cannot induce complete MH[7,8], while azathioprine is able to achieve MH in patients with CD, but with a delayed onset of action[9,10]. The introduction of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α antibody therapy has changed the approach to the management of CD patients, mainly as a result of the rapid effects of biologic therapy[11,12]. Numerous studies have demonstrated MH in patients with CD who were treated with infliximab[12-15].

Conventionally, treatment escalation with the use of increasingly potent immunosuppressants has been performed in a stepwise fashion, such that the most potent therapies including TNF antibodies and surgery are reserved for patients who have failed to respond to (or tolerate) milder treatments. Indeed, this approach, which is termed “step-up” treatment, has recently been challenged, and an aggressive “top-down” strategy has been advocated instead, and supported by evidence that early use of anti-TNF therapies induces higher remission rates in CD[12-15]. In addition, immunomodulators and biologic agents might be able to change the natural history of the disease mainly when introduced early in the course of the disease[16,17]. Treatment strategy for IBD should be tailored according to the risk that some patients (e.g., age < 40 years at diagnosis, and disease location in the ileum) could develop disabling disease[18-20]. Indeed, these patients are exactly those thought most likely to benefit from top-down therapy[21].

In this study, we aimed to assess by double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) the outcome of top-down treatment with infliximab and azathioprine in terms of induction and maintenance of remission efficacy, as well as MH in patients with early active moderate to severe CD naïve to treatment.

This was an open-label, prospective controlled study. Eligible patients were at least 18 years old and had newly diagnosed moderate to severe active CD naïve to treatment, with a Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score between 220 and 450 and with ileal and colonic mucosal ulcerations that were observed by DBE. Patients were excluded from the study if they had fibrostenotic or fistulizing CD or penetrating disease (intraabdominal masses, abscesses and/or fistula) revealed by computed tomography enterography (CTE). Additional exclusion criteria were diabetes; history of tuberculosis; hepatitis B virus, HIV or hepatitis C virus infection; regular use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; current or intended pregnancy; lactation; peptic ulcer disease; and chronic renal, hepatic or heart failure. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ruijin Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

DBE (EN-450 P5/20, Fujifilm, China) was performed up to the site 1.5-2 m proximal to the ileocecal valve via the retrograde route at baseline (week 0), at weeks 30 and 54, and at the end of the study (week 102) by one of the authors (JZ) who was unaware of the patient’s clinical status and treatment category to assess MH of CD. All lesions were graded using CDEIS as described by Mary and Modigliani for French GETAID[22].

Before the study, all patients underwent thorough clinical assessment, routine hematological and biochemical tests, and assessment of disease severity according to CDAI, tuberculin skin test with purified protein derivative, chest X-ray, CTE, and DBE. Patients received early induction therapy with infliximab (Remicade; Xi’an-Janssen, China) at a dose of 5 mg/kg, which was administered intravenously in 250 mL saline solution over 2 h at weeks 0, 2, 6, 14, 22 and 30 (Group I), or prednisone at a dose of 1 mg/kg per day for 7-14 d followed by a tapering schedule of 6-12 wk (Group II). All patients received azathioprine (Imuran; GlaxoSmithKline, Brentford, Middlesex, United Kingdom) at doses of 1.0-2.5 mg/kg per day from week 6 onwards (starting with an initial dose of 50 mg followed by a schedule of increasing dose of 25 mg biweekly until the maximum tolerated dose). Patients continuing to experience flares/lack of response/intolerance to medication discontinued the treatment at the investigator’s discretion. Patients were assessed at weeks 0, 2, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 14, and every 8 wk onwards. At each visit or on the occasion of relapse, clinical assessment, laboratory tests, check for adverse events and compliance, and CDAI calculations were performed.

The primary endpoints of this study were deep remission rates as defined by CDAI score < 150 plus complete MH at weeks 30 and 54, and at the end of the trial in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population. Secondary endpoints included the time to achieve clinical remission; clinical remission rates at weeks 2, 6, 14, 22, 30 54 and 102; and improvement of CDEIS scores at weeks 30 and 54 relative to baseline. Complete MH was defined as complete absence of mucosal ulcerations that were observed at baseline. Clinical remission was defined by CDAI score ≤ 150. Deep remission was defined as CDAI score < 150 plus complete MH. Endoscopic response was defined as a decrease in CDEIS score of > 5. Endoscopic remission was defined as CDEIS score < 6. Complete endoscopic remission was defined as CDEIS score < 3[23]. Patients who received a drug not allowed by the protocol, who had surgery for CD, or who discontinued follow-up due to lack of efficacy or loss of response, were judged to have failed treatment, irrespective of CDAI score.

Safety was assessed in terms of the incidence of adverse events, changes in vital signs, and routine laboratory measures monitored during each infusion and at each study visit. Infusion reactions were defined as any adverse experience that occurred during or within 1 h after infusion. Serum sickness-like reactions were defined as a cluster of features (myalgia and/or arthralgia with fever and/or rash) occurring 1-14 d after reinfusion of infliximab.

All patients who were enrolled were included in the ITT population. Patients who withdrew from the study, or did not have a value at an originally scheduled visit, and those with missing CDAI or CDEIS scores had their last value carried forward for these analyses. ITT analyses of the endpoints were performed. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). Qualitative variables are described as n and percentage and comparison of ratios was tested by χ2 test. Quantitative variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range depending on data distribution. Comparison of continuous variables was performed using Student’s t-test depending on data distribution. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The time-to-event distribution of the treatment arms was performed using a life-table analysis.

From February 2009 to February 2012, 77 eligible patients with newly diagnosed moderate to severe active ileocolonic CD naïve to treatment were enrolled in this open-label, prospective controlled study. For results up to 102 wk, the last completed visit was on January 2, 2014. Thirty-eight patients were allocated to Group I and 39 patients to Group II. The baseline demographic clinical characteristics of these patients were similar in the treatment groups (Table 1).

| Group I | Group II | All patients | P value | |

| (n = 38) | (n = 39) | (n = 77) | ||

| Age at onset (yr), median (IQR) | 24 (19-28) | 27 (19-32) | 25 (19-31) | 0.259 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 22 (57.9) | 25 (64.1) | 47 (61.0) | 0.577 |

| Median disease duration (wk, IQR) | 10 (4-20) | 10 (4.5-18) | 10 (4-20) | 0.854 |

| CDAI, median (IQR) | 280 (247-347) | 274 (258-340) | 279 (251-346) | 0.699 |

| CDEIS, mean (SD) | 13.7 ± 4.4 | 13.2 ± 4.0 | 13.5 ± 4.1 | 0.708 |

Efficacy analyses were performed according to the ITT principle. By week 30, the higher proportion of patients in Group I (44.7%; 17/38) than in Group II (17.9%; 7/39) who were in deep remission approached statistical significance (P = 0.011) (Table 2). The response to initial infusion of infliximab was more rapid than to induction therapy with corticosteroids, with 26.3% of patients in remission in Group I and 2.6% in Group II at week 2. Significantly, more patients in Group I were in clinical remission than in Group II at weeks 6, 22 and 30 (P < 0.05) (Figure 1). The median time to clinical remission was longer in Group II (14.2 wk) than in Group I (6.8 wk, P = 0.009) (Figure 2). The rates of clinical remission and deep remission were higher at weeks 54 and 102 in Group I, but these differences were not significant.

| Group I | Group II | P value | |

| (n = 38) | (n = 39) | ||

| Patients with clinical remission | |||

| Week 2 | 10 (26.3) | 1 (2.6) | 0.003 |

| Week 6 | 25 (65.8) | 11 (28.2) | 0.001 |

| Week 14 | 27 (71.1) | 21 (53.84) | 0.119 |

| Week 22 | 27 (71.1) | 18 (46.2) | 0.027 |

| Week 30 | 26 (68.4) | 17 (43.6) | 0.028 |

| Week 54 | 27 (71.1) | 22 (56.4) | 0.182 |

| Week 102 | 31 (81.5) | 27 (69.2) | 0.209 |

| Median clinical remission time (wk) | 6.8 | 14.2 | 0.009 |

| Patients with MH at week 30 | 17 (44.7) | 7 (17.9) | 0.011 |

| Patients with deep remission at week 30 | 17 (44.7) | 7 (17.9) | 0.011 |

| Endoscopic response at week 30 (decrease in CDEIS score > 5) | 30 (78.9) | 19 (48.7) | 0.006 |

| Endoscopic remission at week 30 (CDEIS score < 6) | 23 (60.5) | 12 (30.8) | 0.009 |

| Complete endoscopic remission at week 30 (CDEIS score < 3) | 14 (36.8) | 8 (20.5) | 0.113 |

| Patients with MH at week 54 | 20 (52.6) | 14 (35.9) | 0.139 |

| Patients with deep remission at week 54 | 20 (52.6) | 14 (35.9) | 0.139 |

| Endoscopic response at week 54 (decrease in CDEIS score > 5) | 32 (84.2) | 30 (77.0) | 0.420 |

| Endoscopic remission at week 54 (CDEIS score < 6) | 31 (81.6) | 29 (74.4) | 0.445 |

| Complete endoscopic remission at week 54 (CDEIS score < 3) | 18 (47.4) | 18 (46.2) | 0.915 |

| Patients with MH at week 102 | 22 (57.9) | 15 (38.5) | 0.088 |

| Patients with deep remission at week 102 | 22 (57.9) | 15 (38.5) | 0.088 |

| Maximum tolerated dose of azathioprine (mg/kg) , mean (SD) | 1.73 ± 0.18 | 1.71 ± 0.19 | 0.748 |

At week 30, endoscopic response, based on CDEIS, occurred in 30/38 patients (78.9%) in Group I, compared with 19/39 patients (48.7%) in Group II (P = 0.006). At week 30, a significantly higher proportion of patients in Group I demonstrated endoscopic remission compared with patients in Group II (60.5% vs 30.8%; P = 0.009). Complete endoscopic remission rate was 36.8% for patients in Group I and 20.5% in Group II at week 30 (P = 0.113). The rates of endoscopic response, endoscopic remission and complete endoscopic remission were greater at week 54 in Group I, but these differences were not significant. The maximum tolerated dose of azathioprine was 1.73 mg/kg for patients in Group I and 1.71 mg/kg in Group II (P = 0.748).

Thirty-four (89.5%) patients in Group I developed drug-related side effects compared with 33 (84.6%) in Group II (Table 3). The most common adverse effects were headache, nausea and abdominal pain. Leukopenia was observed in seven patients (18.4%) in Group I and nine (23.1%) in Group II. Infusion reactions generally characterized by headache, dizziness, nausea, injection-site irritation, flushing, chest pain, dyspnea and pruritus occurred in 6/228 (2.6%) infliximab infusions. Infections occurred in 10.5% (4/38) of patients in Group I and 10.3% (4/39) in Group II; all of which resolved with appropriate medical therapy. There were no unusual or severe infections. Treatment with thiopurines resulted in acute pancreatitis (n = 1) in Group I and alopecia (n = 1) in Group II. Increased aspartate aminotransferase was seen in one patient in each group. Amenorrhea occurred in two (5.3%) patients in Group I and one (2.6%) in Group II. No deaths or cancer occurred during the study.

| Group I | Group II | All patients | P value | |

| (n = 38) | (n = 39) | (n = 77) | ||

| Patients with any adverse events | 34 (89.5) | 33 (84.6) | 77 (87.0) | 0.737 |

| Adverse events leading to discontinuation of study drug | 5 (13.2) | 4 (10.3) | 9 (11.7) | 0.663 |

| Infusion reaction | 5 (13.2) | - | - | - |

| Serum-sickness-like reactions | 0 | - | - | - |

| Infection | 4 (10.5) | 4 (10.3) | 8 (10.4) | 1.000 |

| Headache | 6 (15.8) | 7 (17.9) | 13 (16.9) | 1.000 |

| Nausea | 6 (15.8) | 9 (23.1) | 15 (19.5) | 0.420 |

| Abdominal pain | 7 (18.4) | 11 (28.2) | 18 (23.4) | 0.310 |

| Acute pancreatitis | 1 (2.6) | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 0.494 |

| Alopecia | 0 | 1 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) | 1.000 |

| Amenorrhea | 2 (5.3) | 1 (2.6) | 3 (3.9) | 0.615 |

| Elevation of transaminase | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (2.6) | 1.000 |

| Leukopenia | 7 (18.4) | 9 (23.1) | 16 (20.8) | 0.615 |

| Tuberculosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Colon cancer | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Hematologic cancer | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

Corticosteroids are highly effective in inducing clinical remission in patients with chronic active CD[24,25]. However, their role is primarily ameliorative because they are ineffective in maintaining remission or healing mucosal lesions[7,8]. The thiopurines azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine have been used in the treatment of CD and UC for > 40 years and been the drug of choice in steroid-dependent patients. Despite their slow-acting defect, these agents have demonstrated efficacy in inducing and maintaining remission, and in producing MH[26,27]. Infliximab is a monoclonal IgG1 antibody against TNF-α, and has been proven effective for Crohn’s CD since 1995, with rapid effects[11,12,28]. Trial data demonstrate that infliximab is effective for inducing remission of active CD, healing fistulizing CD, preventing relapse once in remission, and healing mucosal ulcerations[12-14,26,29]. The results of the current study showed earlier clinical remission and MH in infliximab/azathioprine-treated patients compared with corticosteroid/azathioprine-treated patients with moderate to severe ileocolonic CD.

The timing of immunomodulator and biologic therapy has been hotly debated in recent years. Conventionally, treatment guidelines generally recommend initiating treatment with first-line agents, including mesalamine and systemic corticosteroids, followed by immunosuppressants, with anti-TNF therapies reserved for patients in whom conventional therapies have failed[30-32]. This treatment strategy, which is termed step-up, is suboptimal for patients with progressive or treatment-refractory disease, who will continue to experience disease-related morbidity and risk of the development of complications. Indeed, this approach has recently been challenged, and an aggressive top-down strategy was advocated instead, and supported by evidence that early use of anti-TNF therapies induces higher remission rates in CD[15,21,29]. Using data from the EXTEND (Extend the Safety and Efficacy of Adalimumab Through Endoscopic Healing) trial, Sandborn et al[33] found higher rates of MH with adalimumab in patients with shorter disease duration.

An operational definition of early CD is essential to assess whether early intervention algorithms have greater efficacy than conventional step care. Recently, such a definition has been proposed by Peyrin-Biroulet et al[34]. The essential components of the definition are disease duration < 2 years and no previous treatment with immunosuppressive agents or TNF antagonists. In addition, the absence of existing bowel damage is an important modifier for this definition. The high rate of deep remission observed in the current study may be due to initiation of anti-TNF therapies early after the onset of symptoms of CD in patients who were naïve to treatment, and the exclusion of patients with fibrostenotic or abdominal fistulizing CD revealed by CTE.

CD is a progressive condition, characterized by frequent development of CD-related complications, such as internal fistulas and abscesses, perianal fistulas and bowel strictures. One of the key factors determining the natural history of CD is disease duration, because an increasing number of complications have been described over time. Louis et al[1] assessed retrospectively the evolution of the disease after 1-25 years since diagnosis. At diagnosis, 73.7% of patients had an inflammatory phenotype, while at 20 years, only 12% had this phenotype and 32% and 48.8% had stricturing and penetrating behavior, respectively. Lakatos et al[35] observed a change in disease behavior in 30.8% of patients with an initially non-stricturing, non-penetrating disease behavior after a mean disease duration of 9.0 ± 7.2 years.

CTE allows visualization of the entire bowel wall, multiplanar imaging, no obscuration of small bowel loops due to superimposition, and better detection of abscesses, fistulas, strictures and mesenteric abnormalities[36-38], therefore, it has played an increasing role in assessment of patients with CD. Differentiation of fibrotic strictures from inflammatory strictures is important because acute inflammation is treated medically, while fibrotic strictures are treated with invasive procedures (dilatation or excision). Hara et al[39] found that scar tissue may have low homogenous enhancement on CT, which differs from the lower attenuation bowel wall edema in acute inflammatory CD. In population-based studies, 19%-36% of patients newly diagnosed with CD present with bowel damage, that is, disease complications such as strictures, fistulas or abscesses[3,18,40,41]. The median time from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis was 10 wk in the current study. Despite the inclusion criterion of newly diagnosed patients naïve to treatment, the existing irreversible bowel damage may reduce efficacy. The relatively high rate of deep remission in this study can be attributed in part to the exclusion of patients with luminal fibrostenotic or abdominal fistulizing CD revealed by CTE in screening.

However, although trial evidence supports early aggressive therapy, there is concern around prohibitive costs regarding implementation of such a treatment strategy in all IBD patients. Infliximab is the only anti-TNF agent for the treatment of IBD patients that is available in the Chinese market. The standard national health insurance reimbursement does not cover infliximab treatment for IBD patients. In view of the fact that cultural values, economical and legal issues may differ from one country to another, selection criteria for patients who are candidates for top-down treatment are essential in such a developing country. Studies have shown that age < 40 years at diagnosis, disease location in the terminal ileum, and penetrating/stricturing complications are associated with higher risk of surgery[18-20]. Similarly, progression to complicated disease is more rapid in those with small bowel than colonic disease[40]. Patients with a high risk of developing medically irreversible complications are exactly those thought most likely to benefit from top-down therapy[21]. In the current study, we included recently diagnosed CD patients with a median age of 25 years and small bowel involvement naïve to treatment, resulting in encouraging deep remission rates at weeks 30 and 54. Nevertheless, further study is needed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of early top-down treatment, including the impact on hospitalization, surgery, work attendance, and productivity.

Historically, the therapeutic goals of induction and maintenance of clinical remission seemed insufficient to change the natural history of IBD. The concept of deep remission is a recently introduced endpoint, which includes clinical remission and MH. The latter is usually assessed by endoscopy in CD and UC and defined as the absence of ulcers[42]. Evidence has accumulated to show that MH can alter the course of IBD[42-45]. MH has now emerged as an important treatment goal for patients with IBD. The EXTEND trial[33] was the first study designed with MH measured by ileocolonscopy as the primary endpoint in CD. The percentage of patients from the continuous adalimumab group who had MH at week 12 was 27%, compared with 13% for the induction-only/placebo group (P = 0.056). The difference in MH rate at week 52 reached statistical significance, with 24% of patients in the continuous adalimumab group and none of the patients who remained on placebo during the double-blind period achieving healing at week 52 (P = 0.001). In the current study, MH was measured by DBE. The deep remission and MH rates at weeks 30, 54 and 102 were 44.7%, 52.6% and 57.9% in Group I compared with 17.9%, 35.9% and 38.5% in Group II. There has been a strong trend towards earlier deep remission with infliximab as induction therapy. The 30-wk evaluation showed a significantly higher MH rate in Group I than in Group II. There was a higher proportion of patients in deep remission at weeks 54 and 102 in Group I, although there were no significant between-group differences. In our experience, the optimal time point for the first follow-up by DBE was between 30 and 54 wk after treatment in Group I and at least 54 wk after treatment in Group II, which conformed to our previous study[46]. The benefits of early MH were recognized before approval of biologic therapies for IBD[47]. A population-based cohort study confirmed that MH had a significant impact on disease outcome in patients with UC. In patients with UC, 3/178 patients (2%) with MH at 1 year underwent colectomy by 5 years as compared with 13/176 patients (7%) without MH at 1 year (P = 0.002)[47]. Colombel et al[48] indicated that achievement of early MH (i.e., endoscopy subscores of 0 or 1 at week 8) after treatment with infliximab may lead to better long-term clinical outcomes for patients with moderate to severe active UC. The study of long-term outcome with regard to early MH of CD is warranted.

The small bowel is the most commonly involved site of the gastrointestinal tract in CD. In nearly half of patients, CD involves both the large and small bowel, and in another third of patients, only the small bowel is involved, while it is least common (about 20%) to have disease confined to the colon. The development capsule endoscopy in 2001 and DBE in 2004[49] made possible the endoscopic examination of the entire small bowel. The growing experience with DBE in patients with CD reported in the literature is modifying the indications for morphological investigations in this framework and the management of patients. A study of DBE demonstrated that, in a high percentage of patients, ileal involvement in CD may be outside the range of ileocoloscopy[50]. In the current study, MH was assessed by DBE for the first time in patients with CD treated with biologic agents. At baseline, ileal lesions proximal to the terminal ileum were found in 24 and 26 patients in Group I and Group II, respectively. Ileal lesions proximal to the terminal ileum without terminal ileal involvement were found in 10 and 15 patients in Group I and Group II, respectively. At week 102, ileal lesions proximal to the terminal ileum without terminal ileal or colonic lesions were detected in three and two patients in Group I and Group II, respectively (in other words, these five patients may be classified with MH using conventional ileocolonoscopy). Therefore, DBE may identify lesions in the small bowel beyond the reach of conventional ileocolonoscopy and undoubtedly allow for a more comprehensive and objective measurement of MH for CD involving the small bowel, which may have an impact on the cessation of medication and regime change. At present, there is no standardized and validated small intestine mucosal disease scoring index that can be applied to DBE findings. Existing endoscopic scores for CD have only been validated for conventional ileocolonoscopy that include CDEIS and the Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease. In our study, all lesions were graded using CDEIS, which may have relative weight deviation between colon and small bowel in terms of scoring. Establishment of a feasible score correlating with clinical disease activity for assessing the activity or severity of small bowel involvement in CD by DBE is necessary.

In our study, 15 patients who developed hemorrhage were successfully treated with infliximab (data not shown). Several case reports[51] demonstrated that infliximab was effective in stopping the bleeding and promoting MH, which may be related to its anti-TNF-α effect. The benefit of infliximab to treat hemorrhagic CD should be evaluated in a further study.

Our study had three limitations. First, this was an open-label study, which introduced bias in terms of evaluating subjective symptom scores. Second, DBE was used to evaluate macroscopic MH at weeks 30, 54 and 102, but not all patients underwent histological evaluation. Using biopsy or miniprobe confocal laser endomicroscopy via double-balloon endoscopy may provide histological evidence of MH as a more objective outcome for disease activity assessment, which may be used to guide safe discontinuation of therapy in patients with IBD. Third, infliximab concentration or antibodies to infliximab were not detected in the current study. It has been shown that the concurrent use of immunosuppressants is associated with higher rates and a longer duration of response to infliximab in CD patients[52]. In several trials, there is a trend for a lower incidence of development of antibodies to infliximab and infusion reaction with concomitant use of corticosteroids or immunomodulators[12,36,53]. Hürlimann et al[54] observed in patients with rheumatoid arthritis that infliximab could reduce the clearance of azathioprine from serum. In the current study, the difference of maximum tolerated dose of azathioprine in the two groups was not statistically significant. However, the risk of opportunistic infection and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in patients with long-term use of combined anti-TNF biologic agents and immunomodulators, cost, as well as concern about pregnancy should be considered simultaneously.

The results of this study indicate that maintenance therapy with azathioprine, after induction therapy with infliximab, provides important benefits for the treatment of patients with early CD compared with induction therapy with corticosteroids. The beneficial outcome of the former does not seem to be restricted to deep remission, but also extends to the time interval until remission is achieved.

In conclusion, early treatment with infliximab followed by azathioprine-based top-down strategies, as compared with step-up treatment with a conventional induction regimen with corticosteroids followed by azathioprine, resulted in significantly higher rates of clinical remission and MH at week 30, and corticosteroid-sparing effect among patients with early active moderate to severe ileocolonic CD naïve to treatment.

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a transmural inflammatory disorder that may involve various sites of the gastrointestinal tract, including the terminal ileum in 40%-70% of the cases. The majority of CD patients experience a progressive course that transits from pure inflammatory lesions to destructive complications such as stricture, fistula and abscess. Induction and maintenance of clinical remission seemed insufficient to change the natural history of CD.

Mucosal healing (MH) as a therapeutic endpoint has recently become more widely incorporated into clinical trials, in addition to more traditional subjective clinical activity indices, because it has been shown to reduce the likelihood of clinical relapse, reduce the risk of future surgery, and reduce hospitalization. The concept of “deep remission” is a recently introduced endpoint, which includes clinical remission and MH. “Step-up” treatment strategy has recently been challenged, and an aggressive “top-down” strategy has been advocated instead and supported by evidence that early use of anti-TNF therapies induces higher remission rates in CD.

Optimal treatment strategies in patients with CD who are candidates for top-down treatment are still debated. The authors performed a generally well-designed prospective trial of infliximab as induction therapy plus azathioprine (top-down treatment strategy) vs prednisone as induction therapy plus azathioprine in treatment-naïve patients with CD. This is the first study designed with deep remission as the primary endpoint. Furthermore, MH is assessed with double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) for the first time in patients with CD treated with biologic agents.

DBE may identify lesions in the small bowel beyond the reach of conventional ileocolonoscopy and undoubtedly allow for a more comprehensive and objective measurement of MH in CD involving the small bowel, which may have an impact on the cessation of medication and regime change.

The concept of deep remission includes clinical remission and MH. The essential components of the definition of early CD are disease duration < 2 years and no previous treatment with immunosuppressive agents or tumor necrosis factor antagonists. In addition, the absence of existing bowel damage is an important modifier for this definition.

In general, the study design was rigorous and thoughtfully explained. The unique component of this study was the utilization of DBE for assessment of MH. The demographics of the study were also unique, because East Asian individuals with IBD are an understudied population.

P- Reviewer: Harper JW, Kopylov U S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Louis E, Collard A, Oger AF, Degroote E, Aboul Nasr El Yafi FA, Belaiche J. Behaviour of Crohn’s disease according to the Vienna classification: changing pattern over the course of the disease. Gut. 2001;49:777-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 684] [Cited by in RCA: 705] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cosnes J, Cattan S, Blain A, Beaugerie L, Carbonnel F, Parc R, Gendre JP. Long-term evolution of disease behavior of Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8:244-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 981] [Cited by in RCA: 979] [Article Influence: 42.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Thia KT, Sandborn WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Loftus EV. Risk factors associated with progression to intestinal complications of Crohn’s disease in a population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1147-1155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 481] [Cited by in RCA: 577] [Article Influence: 38.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chow DK, Leong RW, Lai LH, Wong GL, Leung WK, Chan FK, Sung JJ. Changes in Crohn’s disease phenotype over time in the Chinese population: validation of the Montreal classification system. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:536-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Freeman HJ. Natural history and clinical behavior of Crohn’s disease extending beyond two decades. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37:216-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nos P, Garrigues V, Bastida G, Maroto N, Ponce M, Ponce J. Outcome of patients with nonstenotic, nonfistulizing Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1771-1776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Modigliani R, Mary JY, Simon JF, Cortot A, Soule JC, Gendre JP, Rene E. Clinical, biological, and endoscopic picture of attacks of Crohn’s disease. Evolution on prednisolone. Groupe d’Etude Thérapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires Digestives. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:811-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 529] [Cited by in RCA: 477] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Olaison G, Sjödahl R, Tagesson C. Glucocorticoid treatment in ileal Crohn’s disease: relief of symptoms but not of endoscopically viewed inflammation. Gut. 1990;31:325-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | D’Haens G, Geboes K, Ponette E, Penninckx F, Rutgeerts P. Healing of severe recurrent ileitis with azathioprine therapy in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1475-1481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mantzaris GJ, Christidou A, Sfakianakis M, Roussos A, Koilakou S, Petraki K, Polyzou P. Azathioprine is superior to budesonide in achieving and maintaining mucosal healing and histologic remission in steroid-dependent Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:375-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Targan SR, Hanauer SB, van Deventer SJ, Mayer L, Present DH, Braakman T, DeWoody KL, Schaible TF, Rutgeerts PJ. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 to tumor necrosis factor alpha for Crohn’s disease. Crohn’s Disease cA2 Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1029-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2328] [Cited by in RCA: 2268] [Article Influence: 81.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541-1549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2987] [Cited by in RCA: 3055] [Article Influence: 132.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rutgeerts P, Diamond RH, Bala M, Olson A, Lichtenstein GR, Bao W, Patel K, Wolf DC, Safdi M, Colombel JF. Scheduled maintenance treatment with infliximab is superior to episodic treatment for the healing of mucosal ulceration associated with Crohn’s disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:433-642; quiz 464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 409] [Cited by in RCA: 400] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rutgeerts P, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W. Comparison of scheduled and episodic treatment strategies of infliximab in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:402-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 700] [Cited by in RCA: 677] [Article Influence: 32.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | D’Haens G, Baert F, van Assche G, Caenepeel P, Vergauwe P, Tuynman H, De Vos M, van Deventer S, Stitt L, Donner A. Early combined immunosuppression or conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease: an open randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371:660-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 922] [Cited by in RCA: 940] [Article Influence: 55.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kugathasan S, Werlin SL, Martinez A, Rivera MT, Heikenen JB, Binion DG. Prolonged duration of response to infliximab in early but not late pediatric Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3189-3194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hommes D, Baert F, Van Assche G. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the ideal management for Crohn’s disease, top-down versus step-up strategies. Gastroenterology. 2005;128 Suppl 2:A577. |

| 18. | Solberg IC, Vatn MH, Høie O, Stray N, Sauar J, Jahnsen J, Moum B, Lygren I. Clinical course in Crohn’s disease: results of a Norwegian population-based ten-year follow-up study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1430-1438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 502] [Cited by in RCA: 526] [Article Influence: 29.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Henckaerts L, Van Steen K, Verstreken I, Cleynen I, Franke A, Schreiber S, Rutgeerts P, Vermeire S. Genetic risk profiling and prediction of disease course in Crohn’s disease patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:972-980.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Veloso FT, Ferreira JT, Barros L, Almeida S. Clinical outcome of Crohn’s disease: analysis according to the vienna classification and clinical activity. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:306-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | D’Haens GR. Top-down therapy for IBD: rationale and requisite evidence. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:86-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mary JY, Modigliani R. Development and validation of an endoscopic index of the severity for Crohn’s disease: a prospective multicentre study. Groupe d’Etudes Thérapeutiques des Affections Inflammatoires du Tube Digestif (GETAID). Gut. 1989;30:983-989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 634] [Cited by in RCA: 665] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hébuterne X, Lémann M, Bouhnik Y, Dewit O, Dupas JL, Mross M, D’Haens G, Mitchev K, Ernault É, Vermeire S. Endoscopic improvement of mucosal lesions in patients with moderate to severe ileocolonic Crohn’s disease following treatment with certolizumab pegol. Gut. 2013;62:201-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Summers RW, Switz DM, Sessions JT, Becktel JM, Best WR, Kern F, Singleton JW. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study: results of drug treatment. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:847-869. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Malchow H, Ewe K, Brandes JW, Goebell H, Ehms H, Sommer H, Jesdinsky H. European Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study (ECCDS): results of drug treatment. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:249-266. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Markowitz J, Grancher K, Kohn N, Lesser M, Daum F. A multicenter trial of 6-mercaptopurine and prednisone in children with newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:895-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 562] [Cited by in RCA: 524] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Punati J, Markowitz J, Lerer T, Hyams J, Kugathasan S, Griffiths A, Otley A, Rosh J, Pfefferkorn M, Mack D. Effect of early immunomodulator use in moderate to severe pediatric Crohn disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:949-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | van Dullemen HM, van Deventer SJ, Hommes DW, Bijl HA, Jansen J, Tytgat GN, Woody J. Treatment of Crohn’s disease with anti-tumor necrosis factor chimeric monoclonal antibody (cA2). Gastroenterology. 1995;109:129-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 770] [Cited by in RCA: 732] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Rachmilewitz D, Lichtiger S, D’Haens G, Diamond RH, Broussard DL. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1383-1395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2539] [Cited by in RCA: 2376] [Article Influence: 158.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Travis SP, Stange EF, Lémann M, Oresland T, Chowers Y, Forbes A, D’Haens G, Kitis G, Cortot A, Prantera C. European evidence based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: current management. Gut. 2006;55 Suppl 1:i16-i35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 440] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Henriksen M, Jahnsen J, Lygren I, Stray N, Sauar J, Vatn MH, Moum B. C-reactive protein: a predictive factor and marker of inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Results from a prospective population-based study. Gut. 2008;57:1518-1523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lichtenstein GR, Abreu MT, Cohen R, Tremaine W. American Gastroenterological Association Institute medical position statement on corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:935-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 338] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Sandborn WJ, Panaccione R, Thakkar R, Lomax KG, Chen N, Mulani PM, Chao J, Yang M. Duration of Crohn’s disease affects mucosal healing in adalimumab-treated patients: Results from EXTEND. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:S36-S37. |

| 34. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus EV, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ. Early Crohn disease: a proposed definition for use in disease-modification trials. Gut. 2010;59:141-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lakatos PL, Czegledi Z, Szamosi T, Banai J, David G, Zsigmond F, Pandur T, Erdelyi Z, Gemela O, Papp J. Perianal disease, small bowel disease, smoking, prior steroid or early azathioprine/biological therapy are predictors of disease behavior change in patients with Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3504-3510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Fletcher JG. CT enterography technique: theme and variations. Abdom Imaging. 2009;34:283-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Wu YW, Tao XF, Tang YH, Hao NX, Miao F. Quantitative measures of comb sign in Crohn’s disease: correlation with disease activity and laboratory indications. Abdom Imaging. 2012;37:350-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Paulsen SR, Huprich JE, Fletcher JG, Booya F, Young BM, Fidler JL, Johnson CD, Barlow JM, Earnest F. CT enterography as a diagnostic tool in evaluating small bowel disorders: review of clinical experience with over 700 cases. Radiographics. 2006;26:641-657; discussion 657-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Hara AK, Swartz PG. CT enterography of Crohn’s disease. Abdom Imaging. 2009;34:289-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Tarrant KM, Barclay ML, Frampton CM, Gearry RB. Perianal disease predicts changes in Crohn’s disease phenotype-results of a population-based study of inflammatory bowel disease phenotype. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:3082-3093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Wolters FL, Russel MG, Sijbrandij J, Schouten LJ, Odes S, Riis L, Munkholm P, Bodini P, O’Morain C, Mouzas IA. Crohn’s disease: increased mortality 10 years after diagnosis in a Europe-wide population based cohort. Gut. 2006;55:510-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Louis E, Mary JY, Vernier-Massouille G, Grimaud JC, Bouhnik Y, Laharie D, Dupas JL, Pillant H, Picon L, Veyrac M. Maintenance of remission among patients with Crohn’s disease on antimetabolite therapy after infliximab therapy is stopped. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:63-70.e5; quiz e31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 437] [Cited by in RCA: 459] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Sandborn WJ. Current directions in IBD therapy: what goals are feasible with biological modifiers? Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1442-1447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Munkholm P, Langholz E, Davidsen M, Binder V. Disease activity courses in a regional cohort of Crohn’s disease patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:699-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 345] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, Kerremans R, Coenegrachts JL, Coremans G. Natural history of recurrent Crohn’s disease at the ileocolonic anastomosis after curative surgery. Gut. 1984;25:665-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 572] [Cited by in RCA: 569] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Yu LF, Zhong J, Cheng SD, Tang YH, Miao F. Low-dose azathioprine effectively improves mucosal healing in Chinese patients with small bowel Crohn’s disease. J Dig Dis. 2014;15:180-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Frøslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, Vatn MH. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:412-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 834] [Cited by in RCA: 873] [Article Influence: 48.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Colombel JF, Rutgeerts P, Reinisch W, Esser D, Wang Y, Lang Y, Marano CW, Strauss R, Oddens BJ, Feagan BG. Early mucosal healing with infliximab is associated with improved long-term clinical outcomes in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1194-1201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 643] [Cited by in RCA: 728] [Article Influence: 52.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Gay GJ, Delmotte JS. Enteroscopy in small intestinal inflammatory diseases. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1999;9:115-123. [PubMed] |

| 50. | Oshitani N, Yukawa T, Yamagami H, Inagawa M, Kamata N, Watanabe K, Jinno Y, Fujiwara Y, Higuchi K, Arakawa T. Evaluation of deep small bowel involvement by double-balloon enteroscopy in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1484-1489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Belaiche J, Louis E. Severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding in Crohn’s disease: successful control with infliximab. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:3210-3211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Parsi MA, Achkar JP, Richardson S, Katz J, Hammel JP, Lashner BA, Brzezinski A. Predictors of response to infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:707-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Maini RN, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, Smolen JS, Davis D, Macfarlane JD, Antoni C, Leeb B, Elliott MJ, Woody JN. Therapeutic efficacy of multiple intravenous infusions of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody combined with low-dose weekly methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1552-1563. [PubMed] |

| 54. | Hürlimann D, Forster A, Noll G, Enseleit F, Chenevard R, Distler O, Béchir M, Spieker LE, Neidhart M, Michel BA. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha treatment improves endothelial function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation. 2002;106:2184-2187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |