Published online Aug 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10620

Revised: March 27, 2014

Accepted: April 30, 2014

Published online: August 14, 2014

Processing time: 226 Days and 13.7 Hours

AIM: To compare the bowel cleansing efficacy of same day ingestion of 4-L sulfa-free polyethylene glycol (4-L SF-PEG) vs 2-L polyethylene glycol solution with ascorbic acid (2-L PEG + Asc) in patients undergoing afternoon colonoscopy.

METHODS: 206 patients (mean age 56.7 years, 61% male) undergoing outpatient screening or surveillance colonoscopies were prospectively randomized to receive either 4-L SF-PEG (n = 104) or 2-L PEG + Asc solution (n = 102). Colonoscopies were performed by two blinded endoscopists. Bowel preparation was graded using the Ottawa scale. Each participant completed a satisfaction and side effect survey.

RESULTS: There was no difference in patient demographics amongst groups. 4-L SF-PEG resulted in better Ottawa scores compared to 2-L PEG + Asc, 4.2 vs 4.9 (P = 0.0186); left colon: 1.33 vs 1.57 respectively (P = 0.0224), right colon: 1.38 vs 1.63 respectively (P = 0.0097). No difference in Ottawa scores was found for the mid colon or amount of fluid. Patient satisfaction was similar for both arms but those assigned to 4-L SF-PEG reported less bloating: 23.1% vs 11.5% (P = 0.0235). Overall polyp detection, adenomatous polyp and advanced adenoma detection rates were similar between the two groups.

CONCLUSION: Morning only 4-L SF-PEG provided superior cleansing with less bloating as compared to 2-L PEG + Asc bowel preparation for afternoon colonoscopy. Thus, future studies evaluating efficacy of morning only preparation for afternoon colonoscopy should use 4-L SF-PEG as the standard comparator.

Core tip: Same day preparation with 4-L sulfa-free polyethylene glycol (4-L SF-PEG) for afternoon colonoscopy is more effective and better tolerated than consumption the day prior. However, no study has compared different bowel preparation solutions administered in their entirety in the morning of an afternoon colonoscopy. We compared the cleansing efficacy and patient satisfaction of same day ingestion of 4-L SF-PEG vs 2-L PEG solution with ascorbic acid (Asc) in patients undergoing afternoon colonoscopy. We found 4-L SF-PEG to provide superior cleansing with less bloating as compared to 2-L PEG + Asc.

-

Citation: Rivas JM, Perez A, Hernandez M, Schneider A, Castro FJ. Efficacy of morning-only 4 liter sulfa free polyethylene glycol

vs 2 liter polyethylene glycol with ascorbic acid for afternoon colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(30): 10620-10627 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i30/10620.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10620

Colonoscopy is considered the gold standard test for early detection and prevention of colorectal cancer[1-3]. A thorough cleansing of the colon is fundamental for an effective colonoscopy evaluation[4-9]. Inadequate bowel cleansing is associated with lower adenoma detection rates, reduced screening intervals, and patient dissatisfaction[7,8,10]. Furthermore, ineffective bowel preparation leads to increases in costs, duration of procedure, and procedure-related complications[11-17].

Earlier studies have reported that colonoscopies performed in the afternoon are associated with higher rates of inadequate bowel preparation and consequently lower rates of successful completion and adenoma detection[6]. Improvement in preparation quality could increase the completion and success rates of afternoon procedures. Our group previously assessed bowel cleansing adequacy with 4-L polyethylene glycol and electrolytes (PEG + ELS) preparation for afternoon colonoscopies, comparing its administration in the evening prior vs morning of procedure. Morning only 4-L PEG + ELS preparation had superior bowel cleansing and resulted in less bloating and sleep loss[18]. Unfortunately consumption of 4-L PEG + ELS can be poorly tolerated by some patients[19] as they may have trouble consuming such a large volume[20,21]. As a result, 2-L PEG based solutions have been introduced to improve patient compliance and satisfaction with bowel preparations. The addition of ascorbic acid to a 2-L PEG solution has been found to work synergistically with the PEG solution via its osmotic effect and improves its taste[22,23].

The aim of this study was to compare the bowel cleansing efficacy of same day ingestion of 4-L sulfa-free PEG (SF-PEG) vs 2-L PEG solution with ascorbic acid (PEG + Asc) in patients undergoing afternoon colonoscopy. In addition, we compared patient satisfaction, tolerability and side effects.

Adult patients over 18 years of age evaluated at Cleveland Clinic Florida between October 2009 and November 2012 who were scheduled for an afternoon colonoscopy were evaluated for participation in the study. Only outpatients who were scheduled for a screening or surveillance colonoscopy at or after 1 PM were included in the study. Patients with constipation, diarrhea, prior colonic resection, suspicion of bowel obstruction, or any other indication for colonoscopy besides screening or surveillance were excluded. Patients were recruited either during an outpatient office visit to our gastroenterology clinic or via phone. Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to enrollment. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Cleveland Clinic Florida.

Patients were prospectively randomized by a computer generated random table to receive either 4-L SF-PEG or 2-L PEG + Asc solution. We decided to use 4-L SF-PEG to avoid the sulfate “rotten egg” taste of 4-L PEG + ELS. Each packet of SF-PEG (NuLytely®) contains 405 g PEG 3350, 5.72 g sodium bicarbonate, 11.2 g sodium chloride, 1.48 g potassium chloride and one 2.0 g flavor pack. We selected 2-L PEG + Asc as studies have shown that PEG + Asc results in better colon cleansing and higher adenoma detection rate than PEG + bisacodyl (Bis)[24]. Each liter of PEG + Asc (Moviprep®) contains 100 g of PEG 3350, 7.5 g sodium sulfate, 2.7 g sodium chloride, 1 g potassium chloride, 4.7 g Asc, 5.9 g sodium ascorbate, and lemon flavoring. After randomization, study patients were given a prescription for either: 4-L SF-PEG solution or low volume 2-L PEG + Asc solution.

All participants were given written and verbal bowel preparation instructions. Both groups had a normal breakfast the day before their procedure followed by a clear liquid diet for lunch and dinner. Participants in both arms were instructed to begin drinking the preparation at 6 AM and to finish by 10 AM the day of the procedure. Patients randomized to 2-L PEG + Asc drank 16 ounces of clear liquids after each liter of the preparation as recommended by the manufacturer.

Colonoscopies were performed by one of two experienced endoscopists (> 6000 colonoscopies each) on staff at the Cleveland Clinic Florida endoscopy unit. Gastroenterology fellows did not participate in these colonoscopies. High definition 140° field of view Fujinon colonoscopes (model EC-450HL5 and EC-450LS5), a Fujinon digital processor (model EPX-4400), and a 32-inch LCD monitor at a resolution of 1032 × 768 producing a 792, 576 pixel image (at a distance of approximately 2.8 m) were used by both endoscopists for all colonoscopies. All procedures were performed under anesthesiologist administered Propofol.

Endoscopists were blinded to the study group and patients and nurses were told not to disclose which preparation was received. Colonoscopy start time, cecal intubation time, and withdrawal time were recorded by the nursing staff and the physician. Bowel preparation was graded using the Ottawa scale immediately after concluding the procedure. Prior to beginning the study, both endoscopists underwent a calibration exercise to have concordance in bowel preparation scores. Anthropometric measures, indication for the procedure, and findings were recorded by each endoscopist at the time of the colonoscopy.

Upon arrival at the endoscopy unit, patients received a short 15 item survey, which included demographics and questions regarding: potential adverse events, taste, and overall satisfaction of bowel purge solution. Patients were asked to rate survey questions on a 5-point Likert scale of (1 = Strongly agree, 2 = Agree, 3 = Disagree, 4 = Strongly disagree, 5 = N/A).

The Ottawa bowel preparation scale[25] was used to grade the quality of the bowel preparation. In this scale, the colon is divided in three segments (right, middle, and left) and each receives a numerical score on a 5-point scale (0-4). A perfect preparation is defined by a score of 0, whereas, a score of 1 is given if there is clear liquid that does not require suction. A score of 2 correlates to finding liquid that must be suctioned to see the colon wall, a three is equivalent to encountering stool that must be flushed before it can be suctioned and a four is given when there is presence of stool that is not washable. The overall amount of colonic fluid encountered at the time of colonoscopy is graded using a 3-point scale (0-2). No significant fluid is defined by a score of 0, whereas, a large amount of fluid is equivalent to a score of 2. The total Ottawa score is determined by adding up the three segments (0-12) plus the fluid score (0-2).

Collected data was verified with electronic medical records, procedure nursing notes and procedure reports. The number of polyps recorded on the procedure reports corroborated with pathology and nursing notes. The main outcome parameter was bowel cleanliness as measured by the Ottawa scale. Secondary outcome measures included: patient satisfaction and adverse events, polyp detection rate, adenoma detection rate and advanced adenomas. Advanced adenoma was defined as adenomatous polyps having one or more features of: > 1 cm in diameter, high-grade dysplasia, or villous histology.

The sample size was calculated using effect size of 0.3, α of 0.05, power of 0.95, and degree of freedom equal to 1. This resulted in a minimum of 145 patients to show difference between adequacies of bowel preparation between the study groups. Patients who cancelled their colonoscopy or were protocol violations were not included in the statistical analysis. Continuous variables are summarized as mean, with their respective standard deviation. Discrete variables are summarized as frequency (percentage). Total Ottawa scores were tested for skewness, kurtosis, and normal distribution (using D’Agostino-Pearson test). Ottawa Score was plotted on receiver operative curve against the outcome of polyp detection. Hypothesis testing for continuous variables was accomplished through t tests. Categorical variables were tested using Pearson’s χ2. Odds ratios were reported with ninety-five percent confident intervals. When comparing outcomes between 4-L SF-PEG and 2-L of PEG + Asc, the OR were adjusted for; age, gender, and body mass index (BMI). For all statistical analysis, a P value of less than or equal to 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical calculations were made using Medcalc 2011 software (Mariakerke, Belgium).

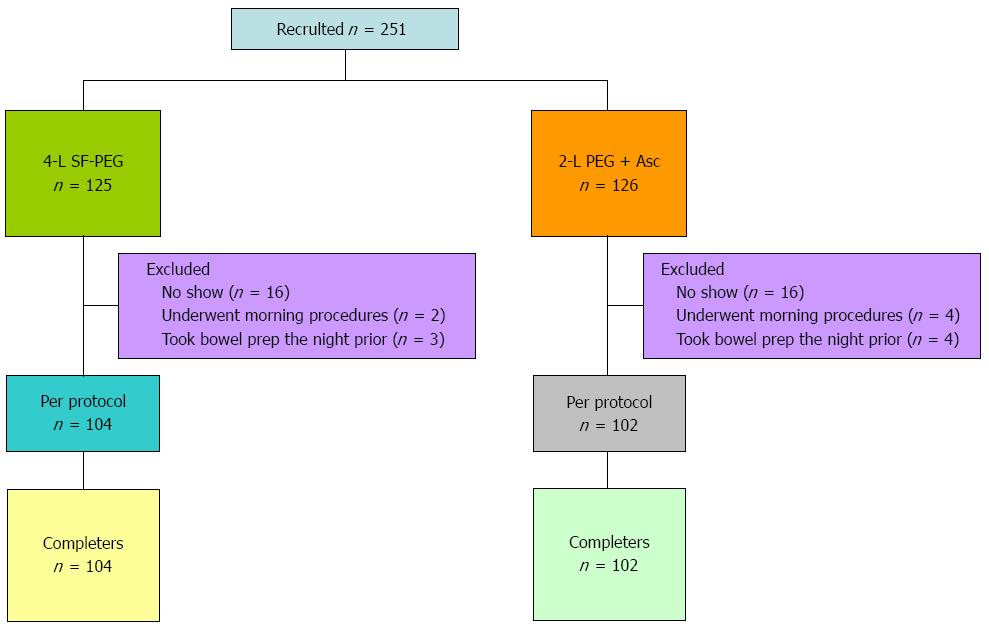

A total of 251 patients consented for the study and 45 of these were excluded either due to a protocol violation (n = 13) or canceling the procedure (n = 32) (Figure 1). Protocol violations included: changing appointment to the morning (n = 6), or not following colon preparation instructions as patient took the bowel preparation the night prior to procedure (n = 7). The study population consisted of 206 patients with 104 receiving 4-L SF-PEG and 102 receiving 2-L PEG + Asc.

Mean age was 56.7 years with 61% males. Forty-nine percent of patients identified themselves as Hispanic and 36% as white. Patients were predominantly educated with 82% having at least some college education. Mean BMI was 29.25 (Table 1). There was a similar distribution of age, gender, race/ethnicity, household income, level of education and BMI among the study groups (Table 1). Forty-four percent of patients had undergone a previous colonoscopy and these were evenly distributed between the intervention arms. Sixty-eight percent of the procedures began prior to 3 PM and the start time was similar for both study groups.

| 4-L SF-PEG n = 104 | 2-L PEG + Asc n = 102 | P value | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age | 55.933 | 7.6161 | 57.402 | 7.9892 | 0.1781 |

| BMI | 29.237 | 6.6711 | 29.266 | 5.4687 | 0.9729 |

| Gender (% male) | 59.6% | 62.7% | 0.6450 | ||

| Had prior colonoscopy | 43.7% | 44.0% | 0.5537 | ||

| Race: | |||||

| African American | 8.7% | 7.8% | 0.8719 | ||

| White | 29.8% | 42.2% | 0.0836 | ||

| Hispanic | 53.8% | 43.1% | 0.1365 | ||

| Other | 7.3% | 6.9% | 0.7767 | ||

| Reason for colonoscopy: | |||||

| Screening | 65.4% | 65.6% | 0.3251 | ||

| History of polyps | 24.0% | 28.4% | 0.7241 | ||

| 1st Degree relative with colon CA | 10.0% | 6.0% | 0.0311 | ||

| Household income: | |||||

| < $25K | 6.52% | 9.28% | 0.4958 | ||

| $25-75K | 32.6% | 25.8% | 0.2327 | ||

| $75K | 23.9% | 20.6% | 0.5502 | ||

| $100K | 37% | 44.3% | 0.2153 | ||

| Education (highest level): | |||||

| Post-graduate | 27.7% | 30.2% | 0.5616 | ||

| College | 55.3% | 51.0% | 0.4707 | ||

| High school | 13.8% | 16.7% | 0.5815 | ||

| Middle school | 3.19% | 1.4% | 0.2892 | ||

| Elementary school | 0% | 1.4% | 0.9940 | ||

| Time of colonoscopy: | |||||

| 1-2 PM | 35% | 33% | 0.8460 | ||

| 2-3 PM | 35% | 31% | 0.6206 | ||

| 3-4 PM | 23% | 28% | 0.3801 | ||

| 4-5 PM | 8% | 7% | 0.8187 | ||

A total of 193 procedures were performed by one endoscopist and the remaining 13 procedures by our second endoscopist. The cecum was reached in all patient procedures. Eight patients required shortening of future screening interval due to unsatisfactory preparation quality (5 assigned to 4-L SF-PEG and 3 to 2-L PEG + Asc). As can be seen in Table 2, 4-L SF-PEG resulted in lower overall Ottawa scores compared to 2-L PEG + Asc (4.2 vs 4.9), (P = 0.0186). The mean Ottawa score for the left colon was statistically lower for 4-L SF-PEG vs 2-L PEG + Asc (1.33 vs 1.57 respectively, P = 0.0224). The mean Ottawa score for the right colon was also statistically lower for 4-L SF-PEG vs 2-L PEG + Asc, 1.38 vs 1.63 respectively (P = 0.0097). There was no difference in Ottawa scores for the mid colon or total amount of fluid (Table 2).

| 4-L SF-PEGn = 104 | 2-L PEG + Ascn = 102 | P value | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Ottawa scores: | |||||

| O-F | 0.635 | 0.6241 | 0.618 | 0.6607 | 0.8499 |

| O-L | 1.327 | 0.7688 | 1.569 | 0.7381 | 0.0224 |

| O-M | 0.875 | 0.8324 | 1.029 | 0.8139 | 0.1799 |

| O-R | 1.375 | 0.6853 | 1.627 | 0.7025 | 0.0097 |

| O-T | 4.212 | 1.9690 | 4.853 | 1.9109 | 0.0186 |

| OT < 6 - optima prep | 84% | 61% | 0.0003 | ||

| Polyp detection rate | 59.6% | 55.9% | 0.5877 | ||

| Total polyps found | 1.25 | 1.5057 | 1.216 | 1.5455 | 0.8719 |

| Adenomas | 38% | 37% | 0.8583 | ||

| Advanced adenomas | 10.6% | 7.8% | 0.4932 | ||

There was no difference with regards to total polyp detection, adenoma detection or advanced adenoma detection rates between the two arms (Table 2). The mean adenoma detection rate in 4-L SF-PEG vs 2-L PEG + Asc was 38% vs 37%, respectively. The mean advanced adenoma detection rate for those receiving 4-L SF-PEG vs 2-L PEG + Asc was 10.6% vs 7.8%, respectively. Although there was no absolute total Ottawa score that resulted in a statistically significant higher polyp detection rate, there was a trend towards an Ottawa score less than 6 resulting in higher polyp detection. Therefore, if we define optimal preparation as an Ottawa score less than 6 this score resulted in better cleansing in the 4-L SF-PEG group (84% vs 61%; P = 0.0003). The 4-L solution was also more likely to result in optimal preparation for total scores lower than 5 (64% vs 46%); P = 0.019. At Ottawa scores of less than seven, there was still a trend favoring 4-L SF-PEG (P = 0.072).

The majority of colonoscopies were started between 1 PM and 3 PM, with 70 cases started between 1 PM and 2 PM, 68 cases started between 2 PM and 3 PM, and 53 cases between 3 PM and 4 PM. Only 4 cases started after 4 PM. Start times did not influence the total Ottawa score or for any individual segment (data not shown).

Data collected from the patient’s questionnaire is summarized in Table 3. Patients randomized to 4-L SF-PEG were less likely to drink the entire amount (79% vs 92%); P = 0.0142. Only one patient from the 4-L SF-PEG group did not consume at least 50% of the bowel preparation. There was no difference in patient satisfaction among the study groups as measured by multiple questions assessing this. However, those randomized to 4-L experienced less bloating than those who received the 2-L PEG + Asc solution (11.5% vs 23.1%), (P = 0.0235). There was a non-significant trend towards reporting a better taste in those who received 4-L SF-PEG (P = 0.0899).

| 4-L SF-PEG n = 104 | 2-L PEG +Asc n = 102 | P value | |

| Mean | Mean | ||

| Patient who drank entire amount of bowel preparation | 78.60% | 92.20% | 0.0142 |

| Patients who would choose bowel prep again | 78.40% | 86.10% | 0.1882 |

| Patients who would recommend their bowel preparation | 82.70% | 86.30% | 0.4788 |

| Patients who felt that the flavor of their bowel prep was pleasant | 70.90% | 59.80% | 0.0899 |

| Patients satisfied with their bowel preparation process | 89.40% | 90.20% | 0.3183 |

| Patients who had difficulty completing their prep | 25.00% | 22.00% | 0.6688 |

| Symptoms: | |||

| Bloating | 11.50% | 23.1 | 0.0235 |

| Abdominal pain | 1.00% | 1.90% | 0.5495 |

| Nausea | 23.10% | 21.20% | 0.7949 |

| Vomiting | 2.90% | 3.80% | 0.6813 |

This prospective, randomized, single-blinded study is the first study comparing the efficacy of same day 4-L SF-PEG vs 2-L PEG + Asc bowel preparation for afternoon colonoscopy. 4-L SF-PEG solution provided superior cleansing as measured by the total Ottawa score and the right and left colon segments. We found no difference in patient satisfaction between the groups but observed less bloating in those that received 4-L SF-PEG.

Afternoon colonoscopies have been reported to have a higher rate of inadequate bowel preparation and failure to complete the procedure[6]. Contrary to these reports, we were able to reach the cecum in all colonoscopies and only eight patients were recommended a shortened follow up screening interval because of inadequate bowel preparation. This data expands on the efficacy of same day bowel preparation regimen for afternoon colonoscopy previously reported by our group[18]. Improved visualization of the right colon seen with 4-L SF-PEG is particularly important given the potential of missed lesions in this segment[26].

For morning colonoscopies, multiple studies have demonstrated PM/AM split dose PEG administration to be superior to day prior full dose preparation in quality of bowel preparation and willingness to repeat same purgative[27]. These reports have led the American College of Gastroenterology to recommend split-dose bowel preparation[28]. For afternoon colonoscopies, however, there is the option of taking the purgative in its entirety in the morning or using a split dose regimen. Although data is limited, existing literature favors morning only preparation for afternoon procedures as opposed to split dose preparation. A study comparing split vs same day sodium picosulfate found same day preparation resulted in better mucosal cleansing with fewer side effects. Another study using split vs same day PEG described similar cleansing efficacy with lower incidence of abdominal pain, superior sleep quality, and less interference with workday in those who received same day preparation[29,30].

There are no published studies comparing different bowel preparation regimens administered in their entirety in the morning of an afternoon procedure but there are two studies comparing split dose 4-L PEG + ELS (non sulfa free) vs 2-L PEG + Asc. The first was published by Ell et al[31] and included 306 patients randomized to split dose PM/AM 4-L or 2-L solutions. Mucosal cleansing of 2-L PEG + Asc was non-inferior to 4-L PEG + ELS. In addition, acceptability and taste were better for low volume 2-L PEG + Asc. However, the study’s target population was inpatients, which as mentioned by the authors, probably included more frail and elderly patients than would be seen in the general screening population. A second study by Corporaal et al[32] compared these two preparations in outpatients undergoing screening and diagnostic colonoscopies. Although not statistically significant, patients who took 4-L PEG + ELS solutions had higher overall successful bowel cleansing than 2-L PEG + Asc, 96% vs 90.6% respectively with no differences in patient satisfaction, taste or side effects. In addition, a recent meta-analysis combined these two studies and found 4-L split dose PEG to yield significantly better excellent or good preparations (OR = 2.27)[33].

Similar to Corporaal et al[32], we found no statistically significant difference in patient satisfaction between 2-L PEG + Asc and 4-L PEG. Patients who took the 4-L SF-PEG preparation reported significantly lower rates of bloating and a trend towards a better flavor (P = 0.08). The 2-L PEG + Asc preparation may have caused more bloating because it contains the artificial sweetener aspartame, which may not be well tolerated by some individuals. Another possible explanation may be the presence of ascorbic acid which can cause abdominal cramps.

Our study showed no significant difference in regards to total polyp detection or adenoma detection between the two groups. A larger study population would be required to evaluate differences in polyp detection rate. We were able to find a statistical trend towards an Ottawa score lower than 6 resulting in higher polyp detection and these scores were more frequently found in the 4-L SF-PEG group.

The strengths of this study lie in its design. The study was prospective, randomized, and single blinded. Confounding factors were accounted for by either excluding symptomatic patients or evaluating variables that have been reported to affect the quality of the preparation such as BMI and level of education. Having only two endoscopists grade bowel preparation diminished inter-observer variability. Additionally, most of the procedures were performed by one endoscopist (193 out of 206), which also decreases inter-observer variability. Many bowel preparation studies use non validated scales or modified versions of validated scales. We used a validated scale to judge bowel preparation, the Ottawa scale, because it is based on objective maneuvers that are required to achieve adequate cleansing such as suctioning or washing whereas other scales evaluate mucosal visibility after cleansing maneuvers are performed. Lastly, it should be noted that no pharmaceutical companies sponsored this study.

We also recognize that the study has several limitations. There was a pre-selected patient sample because we needed patient consent. Therefore, these patients were willing to consume the 4-L SF-PEG solution, which may not reflect the willingness of the general population[33]. Another limitation is that there was not a significant time interval between 2-L PEG + Asc doses. We chose to do this because we felt that long time lags would have resulted in significantly more hours of sleep lost and inconvenience. This could have negatively affected patient satisfaction and bowel preparation compliance. Finally, the time at which the preparation was finalized was not evaluated. A recent study by Seo et al[34] found the optimal interval between the last dose of the agent and colonoscopy start time to be between 3 to 5 h. Nevertheless we found no difference in the quality of the preparation between earlier and later afternoon procedures and colonoscopy start times were similar for both groups.

In conclusion, this is the first study comparing two different methods of bowel preparation (4-L SF-PEG vs 2-L PEG + Asc) administered in their entirety on the same day of an afternoon colonoscopy. Although both preparations achieve adequate bowel preparation, 4-L SF-PEG solution resulted in overall superior cleansing effects as well as in the right and left colon with less associated bloating. There was no difference in patient satisfaction. Based on our findings, we suggest that future studies evaluating morning only preparation for afternoon colonoscopy should use 4-L SF-PEG as the standard comparator.

Adequate adenoma detection can only be achieved with thorough cleansing of the colon. Ineffective bowel preparation can lead to increased costs and procedure-related complications. Afternoon colonoscopies have been found to have higher rates of inadequate bowel preparation and lower adenoma detection. Morning-only consumption of 4-L polyethylene glycol (4-L PEG) for afternoon colonoscopy provides a better quality of preparation and tolerance than ingesting the preparation the day prior.

To compare cleansing efficacy and patient satisfaction of same day ingestion of 4-L sulfa-free PEG (SF-PEG) vs 2-L PEG solution with ascorbic acid (PEG + Asc) in patients undergoing afternoon colonoscopy. Advances in cleansing regimens can result in improved patient compliance and adenoma detection rate.

Contrary to prior studies reporting lower completion rates for afternoon colonoscopies, the authors were able to reach the cecum in all colonoscopies and in only 4% of cases was the interval for future colonoscopy shortened due to inadequate preparation. These findings add to the efficacy of morning only preparation for afternoon procedures. This study is unique because there are no published studies comparing different bowel preparation regimens administered in their entirety in the morning of an afternoon procedure. Similar to these findings, a recent meta-analysis combining two studies comparing split dose 4-L PEG + ELS vs 2-L PEG + ASC found that the 4-L split dose PEG yielded a significantly better bowel preparation. Additionally, this study showed no significant difference in regards to total polyp detection or adenoma detection between the two groups. A larger study population would be required to evaluate differences in polyp detection rate. However, the authors were able to find a statistical trend towards an Ottawa score lower than 6 resulting in higher polyp detection and these scores were more frequently found in the 4L SF-PEG group.

For patients scheduled for an afternoon colonoscopy that consume the preparation in the morning and do not require volume restriction the use of SF-PEG should be first choice.

The paper is well-written, the tables and figures are of high quality, and the authors have clearly worked hard to produce a comprehensive dataset and detailed description of their methods. The results are clearly presented and the conclusions are hardly controversial.

P- Reviewer: Sakamoto T S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Bond JH, Ahnen DJ, Garewal H, Chejfec G. Use of colonoscopy to screen asymptomatic adults for colorectal cancer. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group 380. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:162-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1214] [Cited by in RCA: 1203] [Article Influence: 48.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mostafa G, Matthews BD, Norton HJ, Kercher KW, Sing RF, Heniford BT. Influence of demographics on colorectal cancer. Am Surg. 2004;70:259-264. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O’Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Waye JD, Schapiro M, Bond JH, Panish JF. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977-1981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3107] [Cited by in RCA: 3128] [Article Influence: 97.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Bernstein C, Thorn M, Monsees K, Spell R, O’Connor JB. A prospective study of factors that determine cecal intubation time at colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:72-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hendry PO, Jenkins JT, Diament RH. The impact of poor bowel preparation on colonoscopy: a prospective single centre study of 10,571 colonoscopies. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:745-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sanaka MR, Shah N, Mullen KD, Ferguson DR, Thomas C, McCullough AJ. Afternoon colonoscopies have higher failure rates than morning colonoscopies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2726-2730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, Burnand B, Vader JP. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:378-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 642] [Cited by in RCA: 700] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Harewood GC, Sharma VK, de Garmo P. Impact of colonoscopy preparation quality on detection of suspected colonic neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:76-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 524] [Cited by in RCA: 560] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Thomas-Gibson S, Rogers P, Cooper S, Man R, Rutter MD, Suzuki N, Swain D, Thuraisingam A, Atkin W. Judgement of the quality of bowel preparation at screening flexible sigmoidoscopy is associated with variability in adenoma detection rates. Endoscopy. 2006;38:456-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Parra-Blanco A, Nicolas-Perez D, Gimeno-Garcia A, Grosso B, Jimenez A, Ortega J, Quintero E. The timing of bowel preparation before colonoscopy determines the quality of cleansing, and is a significant factor contributing to the detection of flat lesions: a randomized study. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6161-6166. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Aronchick CA, Lipshutz WH, Wright SH, Dufrayne F, Bergman G. A novel tableted purgative for colonoscopic preparation: efficacy and safety comparisons with Colyte and Fleet Phospho-Soda. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:346-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Radaelli F, Meucci G, Imperiali G, Spinzi G, Strocchi E, Terruzzi V, Minoli G. High-dose senna compared with conventional PEG-ES lavage as bowel preparation for elective colonoscopy: a prospective, randomized, investigator-blinded trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2674-2680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hayes A, Buffum M, Fuller D. Bowel preparation comparison: flavored versus unflavored colyte. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2003;26:106-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Parente F, Marino B, Crosta C. Bowel preparation before colonoscopy in the era of mass screening for colo-rectal cancer: a practical approach. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:87-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, Fanelli RD, Hyman N, Shen B, Wasco KE. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:792-809. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Byrne MF. The curse of poor bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1587-1590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Di Febo G, Gizzi G, Caló G, Siringo S, Brunetti G. Comparison of a new colon lavage solution (Iso-Giuliani) with a standard preparation for colonoscopy: a randomized study. Endoscopy. 1990;22:214-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Varughese S, Kumar AR, George A, Castro FJ. Morning-only one-gallon polyethylene glycol improves bowel cleansing for afternoon colonoscopies: a randomized endoscopist-blinded prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2368-2374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Barkun A, Chiba N, Enns R, Marcon M, Natsheh S, Pham C, Sadowski D, Vanner S. Commonly used preparations for colonoscopy: efficacy, tolerability, and safety--a Canadian Association of Gastroenterology position paper. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:699-710. [PubMed] |

| 20. | DiPalma JA. Preparation for colonoscopy. Colonoscopy. London: Blackwell Sciences 2003; 210-219. |

| 21. | DiPalma JA, Buckley SE, Warner BA, Culpepper RM. Biochemical effects of oral sodium phosphate. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:749-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wilson JX. Regulation of vitamin C transport. Annu Rev Nutr. 2005;25:105-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fujita I, Akagi Y, Hirano J, Nakanishi T, Itoh N, Muto N, Tanaka K. Distinct mechanisms of transport of ascorbic acid and dehydroascorbic acid in intestinal epithelial cells (IEC-6). Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol. 2000;107:219-231. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Cohen LB, Sanyal SM, Von Althann C, Bodian C, Whitson M, Bamji N, Miller KM, Mavronicolas W, Burd S, Freedman J. Clinical trial: 2-L polyethylene glycol-based lavage solutions for colonoscopy preparation - a randomized, single-blind study of two formulations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:637-644. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Rostom A, Jolicoeur E. Validation of a new scale for the assessment of bowel preparation quality. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:482-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 26. | Bressler B, Paszat LF, Vinden C, Li C, He J, Rabeneck L. Colonoscopic miss rates for right-sided colon cancer: a population-based analysis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:452-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kilgore TW, Abdinoor AA, Szary NM, Yust JB, Choudhary A, Matteson ML, Puli SR, Marshall JB, Bechtold ML. Bowel preparation with split-dose polyethylene glycol before colonoscopy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1240-1245. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, Schoenfeld PS, Burke CA, Inadomi JM. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected]. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:739-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 981] [Cited by in RCA: 1059] [Article Influence: 66.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Longcroft-Wheaton G, Bhandari P. Same-day bowel cleansing regimen is superior to a split-dose regimen over 2 days for afternoon colonoscopy: results from a large prospective series. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:57-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Matro R, Shnitser A, Spodik M, Daskalakis C, Katz L, Murtha A, Kastenberg D. Efficacy of morning-only compared with split-dose polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution for afternoon colonoscopy: a randomized controlled single-blind study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1954-1961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ell C, Fischbach W, Bronisch HJ, Dertinger S, Layer P, Rünzi M, Schneider T, Kachel G, Grüger J, Köllinger M. Randomized trial of low-volume PEG solution versus standard PEG + electrolytes for bowel cleansing before colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:883-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Corporaal S, Kleibeuker JH, Koornstra JJ. Low-volume PEG plus ascorbic acid versus high-volume PEG as bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1380-1386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Enestvedt BK, Tofani C, Laine LA, Tierney A, Fennerty MB. 4-Liter split-dose polyethylene glycol is superior to other bowel preparations, based on systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1225-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Seo EH, Kim TO, Park MJ, Joo HR, Heo NY, Park J, Park SH, Yang SY, Moon YS. Optimal preparation-to-colonoscopy interval in split-dose PEG bowel preparation determines satisfactory bowel preparation quality: an observational prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:583-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |