Published online Aug 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10570

Revised: April 6, 2014

Accepted: May 19, 2014

Published online: August 14, 2014

Processing time: 228 Days and 18.1 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the feasibility of a preoperative colonoscopy through a self-expendable metallic stent (SEMS) and to identify the factors that affect complete colonoscopy.

METHODS: A total of 48 patients who had SEMS placement because of acute malignant colonic obstruction underwent preoperative colonoscopy. After effective SEMS placement, patients who showed complete resolution of radiological findings and clinical signs of acute colon obstruction underwent a standard bowel preparation. Preoperative colonoscopy was then performed using a standard colonoscope. If the passage of colonoscope was not feasible gastroscope was used. After colonoscopy, cecal intubation time, grade of bowel preparation, tumor location, stent location, presence of synchronous polyps or cancer, damage to colonoscopy and bleeding, and stent migration after colonoscopy were recorded.

RESULTS: Complete evaluation with colonoscope was possible in 30 patients (62.5%). In this group, adenoma was detected in 13 patients (43.3%). The factors that affected complete colonoscopy were also analyzed: Tumor location at an angle; stent placement at an angle; and stent expansion diameter, which affected complete colonoscopy significantly. However in multivariate analysis, stent expansion diameter was the only significant factor that affected complete colonoscopy. Complete evaluation using additional gastroscope was feasible in 42 patients (87.5%).

CONCLUSION: Preoperative colonoscopy through the colonic stent using only conventional colonoscope was unfavorable. The narrow expansion diameter of the stent may predict unfavorable outcome. In such a case, using small caliber scope should be considered and may expect successful outcome.

Core tip: The assessment of synchronous neoplasm in acute malignant colonic obstruction remains troublesome. In this study, complete colonoscopy through the colonic stent using colonoscope and gastroscope was feasible in 42 patients (87.5%) and the stent expansion diameter was the only significant factor that affected complete colonoscopy. Through this, we might predict the favorable condition regarding preoperative colonoscopy.

- Citation: Kim JS, Lee KM, Kim SW, Kim EJ, Lim CH, Oh ST, Choi MG, Choi KY. Preoperative colonoscopy through the colonic stent in patients with colorectal cancer obstruction. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(30): 10570-10576

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i30/10570.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10570

Full preoperative colonic evaluation in patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer is important because the presence of synchronous neoplasm, which has a reported incidence of 12%-58% for synchronous polyps and 2%-11% for synchronous cancers[1-5] may change the extent of surgery and missed synchronous neoplasm may lead to second surgery or failure of curative resection. Unfortunately, 10%-30% of patients with colorectal cancer present acute colonic obstruction, which precludes complete colonoscopy[6].

The invention of colonic stents led to the conversion of emergency surgery due to malignant obstruction to elective surgery by effective stent placement known as a bridge to surgery. Nevertheless, the assessment of synchronous neoplasm in acute malignant colonic obstruction remains troublesome. Although several radiological modalities, such as computed tomography (CT) colonography and magnetic resonance colonography, have been reported as being useful methods for synchronous neoplasm detection[7,8], the possibility remains of false-positive results because of a lack of reference standards before surgery. For this reason, if feasible, the most reliable and ideal method for the detection of synchronous neoplasm in patients with acute malignant obstruction may be full colonoscopic evaluation after effective self-expendable metallic stent (SEMS) placement. SEMS placement in obstructive colon cancer can create a more dilated lumen by expanding force, which may permit the passage of a colonoscope and the accurate evaluation of the proximal colon above the obstruction site. A previous study reported the feasibility of full colonoscopy through the stents[9]. According to that study, in the majority of patients, it is feasible to perform full preoperative colonoscopy after relief of acute colonic obstruction with SEMS before surgical resection. However, there are no other reports on this subject and no study analyzed the factors associated with the successful passage of a colonoscope through the stent and cecal intubation. Thus, we planned a prospective study to identify factors that are associated with the success of this procedure. The present study was performed to evaluate the feasibility and safety of preoperative colonoscopy through the stent and to identify factors that affect complete colonoscopy in patients who underwent SEMS placement because of acute malignant colonic obstruction.

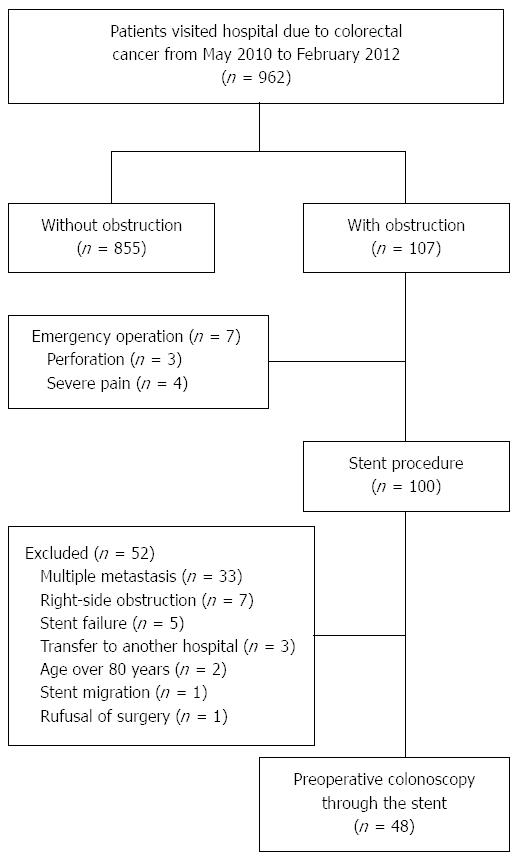

From May 2010 to February 2012, 962 patients with colorectal cancer visited Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital and St. Vincent’s Hospital. Among them, 100 patients underwent endoscopic SEMS placement for acute malignant colorectal obstruction. The diagnosis of colorectal obstruction was established based on the patients’ clinical history, abdominal examination, and plain abdominal radiographs. All patients had endoscopic features of colonic obstruction and a colonoscope with a diameter of 12.2 or 13.2 mm could not pass through the stricture. All patients displayed clinical features of colorectal obstruction, with symptoms of constipation and abdominal distension. Patients were enrolled prospectively in this study if SEMS placement was clinically and technically successful. Suspicious perforation, inoperable cases because of multiple metastasis, technical and clinical failure after SEMS placement, age over 80 years, right-side colon obstruction, and refusal of surgery were exclusion criteria; 52 patients were excluded because of the presence of: technical or clinical failure after SEMS placement (n = 5), multiple metastasis (n = 33), stent migration (n = 1), right-side obstruction (obstruction above the distal transverse colon, n = 7), old age (n = 2), refusal of surgery (n = 1), and transfer to another hospital (n = 3) (Figure 1). Finally, 48 patients underwent preoperative colonoscopy. Before preoperative colonoscopy, informed consents were obtained for both procedure and participation in the study and the procedure performed 1 or 2 d before scheduled surgery. If the preoperative colonoscopy suggested advanced histology such as advanced adenoma or cancer, the operation was delayed until histologic confirmation could be done.

SEMS placement was performed under endoscopic and fluoroscopic control within 24 h of the diagnosis. All procedures were performed by three gastroenterologists, each with at least 5 years of experience in colonoscopy and 3 years of experience in stent-placement procedures. All stents used in this study were uncovered SEMSs (Hanarostent, M.I. Tech Co., Ltd, Seoul, South Korea) with a diameter of 26 mm and a length of 6-16 cm. The stents were delivered through the colonoscope. The appropriate length of the SEMSs selected was one that was adequate to cover the entire stricture, with an extension of about 2 cm beyond both stricture margins. Abdominal radiographs were obtained immediately, 24 h, and 72 h after stent placement to estimate the degree of stent expansion and stent patency and to identify possible complications. The initial technical and clinical success rates after stent placement were evaluated. Initial technical success was defined as the accurate placement of the stent across the entire length of the stricture and opening of the stricture to resolve the bowel obstruction. Clinical success was defined as the ability to defecate within 24-72 h and the relief of obstructive symptoms, without reintervention or procedure-related complications. The narrowest expansion diameter of the stent waist was calculated in reference to the full expanded distal flare (26 mm). The institutional review board approved the study and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Patients who were considered candidates for curative colon resection after complete resolution of radiological findings and clinical signs of acute colon obstruction underwent a standard bowel preparation consisting of the consumption of a 4 L polyethylene glycol/electrolyte lavage solution, for the execution of preoperative colonoscopy. Colonoscopy was then performed using a standard colonoscope (CF-H260AL; diameter, 13.2 mm; Olympus Optical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). If the passage of colonoscope was not feasible due to narrow expanded lumen, gastroscope (GIF-H260; diameter, 9.5 mm; Olympus Optical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) was used instead of colonoscope. Standard intravenous conscious sedation was administered as needed.

During the endoscopic procedure, we evaluated cecal intubation time, presence of synchronous polyps or cancers, stent migration, and mechanical damage to the colon and colonoscope after passage through the stent. The quality of bowel preparation was judged according to the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale[10]. Each region of the colon received a segment score from 0 to 3, and these segment scores were summed for a total score, which ranged from 0 to 9. All polyps and/or synchronous cancers detected during the endoscopic procedures were resected and underwent further histological evaluation. Complete colonoscopy was defined as the successful passage of the colonoscope through the stent, reaching the cecum. Incomplete colonoscopy was defined as unavailable passage of the colonoscope though the stent or failure to reach the cecum, even if the passage of the colonoscope through the stent was successful.

The data presented in this manuscript are expressed as the mean ± SD. Comparisons between categorical variables were made using χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Comparisons between continuous variables were made using the Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare three or more groups. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis with calculations of the area under the curve (AUC) was used to determine the ideal cutoff values for stent expansion diameter predicting successful passage of scope. Logistic regression analysis was used for the multivariate analysis. A P value < 0.05 was accepted as indicative of significance. All statistical analyses were performed using commercially available software (SPSS 17.0 for Microsoft Windows, Chicago, IL).

The mean age of the 48 patients was 63.2 years and 54.1% of the patients were male. The mean BMI of the patients was 23.2. The most common obstruction site was the sigmoid colon (n = 26). The other obstruction sites were descending colon (n = 10), rectosigmoid junction (n = 6), splenic flexure (n = 2), rectum (n = 2), Sigmoid-descending junction (n = 1) and distal Transverse colon (n = 1). The stage of cancer was II in 13 patients, III in 33 patients and IV in 2 patients, which was resectable because of single metastasis to the liver

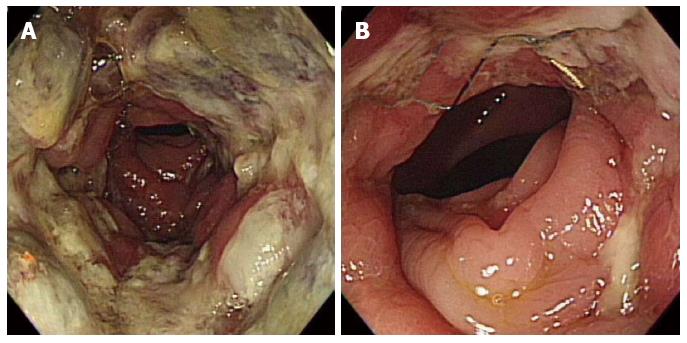

Complete preoperative colonoscopy was possible in 30 out of 48 patients (62.5%) (Figure 2); in the remaining 18 out of 48 patients, complete colonoscopy was not successful because the passage of the colonoscope through the stent was not feasible (n = 17) and because of severe redundancy of the colon after passage of the scope through the stent (n = 1). In patients in whom complete colonoscopy was feasible, the median cecal intubation time was 9 min and 30 s (range, 4 min and 20 s to 15 min and 27 s).

Regarding synchronous neoplasm, 25 adenomas were detected in 13 out of 48 patients (27%) and were removed using biopsy forceps, snares and surgery (included within resection range). The pathology and location of polyps were: 8 adenomas in the ascending colon, 7 adenomas in the transverse colon, 4 adenomas in the descending colon, 3 adenomas in the sigmoid colon, and 3 adenomas in the rectum. Synchronous cancers were detected in 2 patients (4.1%). One synchronous cancer located in the distal rectum was removed via endoscopic submucosal dissection, and the final histological diagnosis was intraepithelial carcinoma. The other synchronous cancer was located in the sigmoid colon, close to the primary cancer, and was included within resection range (Table 1). Regarding complications from the colonoscopy procedure, there was no stent migration after passage and withdrawal of the colonoscope. Minor bleeding, which barely oozed and stopped spontaneously at the stent site, was observed in 8 out of 48 patients (16.6%). Perforation not detected during the procedure occurred in 1 patient (2%), radiological examination performed after the procedure revealed the presence of free air below the diaphragm. However, as there were no symptoms of peritonitis, the operation was performed on the following day, as scheduled. There was no mechanical damage to the colonoscope after passage through the stent. Bowel preparation was done by ingesting 4 L of PEG within 3 h, starting from 6 AM. There were no adverse effects such as vomiting, abdominal pain or severe abdominal distension due to ileus. Bowel preparation was excellent in which the cecum was intubated (n = 30) and the mean ± SD of the preparation score was 8.07 ± 1.47.

| Synchronous polyp (n) | Synchronous cancer (n) | |

| Ascending colon | High-grade adenoma (1) | |

| Low-grade adenoma (7) | ||

| Transverse colon | Low-grade adenoma (7) | |

| Descending colon | Low-grade adenoma (4) | |

| Sigmoid colon | Low-grade adenoma (3) | Adenocarcinoma (1) |

| Rectum | Low-grade adenoma (3) | Adenocarcinoma (1) |

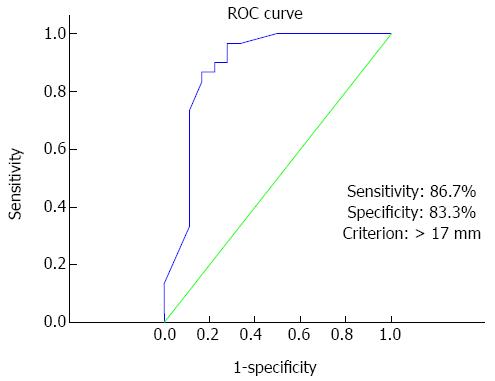

To identify the factors that affected complete colonoscopy, successful cecal intubated complete colonoscopy (n = 30) and incomplete colonoscopy (n = 18) groups were designated and analyzed. There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients regarding gender, age, BMI, operation history, tumor length, tumor staging, tumor location, stent length and time between stent placement and colonoscopy between the 2 groups. Analysis of the incomplete colonoscopy group revealed that tumors located at an angle (splenic flexure, sigmoid-descending junction, and rectosigmoid junction) tended to be more unfavorable to passage of the colonoscope. We classified tumors according to their location at an angle vs nonangle and analyzed them. The proportion of tumors located at an angle in the complete and incomplete groups was 2/30 (6.7%) and 6/18 (33.3%), respectively, and the difference was significant (P = 0.04). If tumors were located near an angle, the proximal or distal side of stent may have extended to the angle portion and lead to an angulated stent; the passage of the colonoscope through the stent was unfavorable in these cases. The proportion of cases in whom stent placement included an angle was significantly lower in the complete colonoscopy group (23.3% vs 55.6%; P = 0.024). The expansion diameter of the stent waist also affected the success of complete colonoscopy (19.96 ± 2.68 mm vs 15.13 ± 2.84 mm; P < 0.01). The results described above are summarized in Table 2. The ROC curve analysis revealed the appropriate cutoff value for the diameter of expanded stent predicting successful complete colonoscopy. A Cutoff value of 17 mm yielded a sensitivity of 86.7% and a specificity of 83.3% in predicting successful passage of scope (AUC = 0.885, 95%CI: 0.760-0.959, P < 0.01, Figure 3). Based on this cutoff value, the patients were divided into 2 groups, with 30 (62.5%) having expansion diameter over 17 mm and 18 (37.5%) having expansion diameter below 17 mm. In multivariate analysis using a logistic regression analysis, the expanded diameter over 17 mm was independently associated with successful complete colonoscopy (OR = 57.968; 95%CI: 5.331-630.297; P < 0.01; Table 3).

| Complete colonoscopy group (n = 30) | Incomplete colonoscopy group (n = 18) | P value | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 65.3 ± 13.6 | 61.3 ± 11.4 | 0.30 |

| Sex (M/F) | 18/12 | 10/8 | 0.76 |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 23.3 ± 3.25 | 23.2 ± 2.96 | 0.86 |

| Abdomen OP | 8 (26.6) | 2 (11) | 0.28 |

| History | |||

| T stage (T3/T4) | 24/6 | 13/5 | 0.53 |

| N stage | 10/9/10 | 3/9/6 | 0.25 |

| (N0/N1/N2) | |||

| Tumor location | 0.13 | ||

| Proximal T colon | 1 | 0 | |

| Splenic flexure | 1 | 2 | |

| Descending | 7 | 2 | |

| SD junction | 1 | 0 | |

| Sigmoid | 17 (56.6) | 9 (50.0) | |

| RS junction | 1 | 5 | |

| Rectum | 2 | 0 | |

| Tumor located at | 2 (6.7) | 6 (33.3) | 0.04 |

| An angle | |||

| Tumor length | 6.25 ± 2.44 cm | 6.06 ± 2.45 cm | 0.79 |

| (mean ± SD) | |||

| Stent placement | 7 (23.3) | 10 (55.6) | 0.02 |

| at an angle | |||

| Stent expansion | 19.96 ± 2.68 | 15.13 ± 2.84 | < 0.01 |

| diameter | |||

| (mean ± SD, mm) | |||

| Stent length | 9.4 ± 2.11 | 8.6 ± 1.37 | 0.19 |

| (mean ± SD, cm) | |||

| Stent placement | 7.93 ± 1.85 | 8.11 ± 1.85 | 0.74 |

| to colonoscopy | |||

| (mean ± SD, d) |

| Odds ratio | 95%CI | Pvalue | |

| Stent diameter ≥ 17 mm | 58.3 | 5.08-668.58 | < 0.01 |

| Stent located at angle | 1.88 | 0.26-13.44 | 0.53 |

| Tumor located at angle | 5.83 | 0.36-92.36 | 0.21 |

Complete preoperative evaluation using additional gastroscope was possible in 12 out of 18 patients (66.6%) who showed unsuccessful passage of colonoscope through the stent. Successful passage of gastroscope through the stent was feasible in 15 out of 18 patients (83.3%) Though successful passage was feasible, the gastroscope could not reach the cecum in 3 patients due to redundancy of the colon and short length of the gastroscope. The overall complete evaluation rate using colonoscope and gastroscope was 87.5% (42/48) which was significantly higher than colonoscope only (62.5%, 30/48) (P < 0.005). Regarding synchronous neoplasm, 10 adenomas were detected in 5 out of 12 patients (41.6%) and were removed using biopsy forceps or snares. No complications were observed after passage of gastroscope.

Full colonic evaluation before surgery in patients with colorectal cancer has been recommended[4]. However, in patients with obstructive colon cancer, preoperative colonoscopy may not be possible because of narrowing of the lumen. In such cases, CT colonography or magnetic resonance colonography may be alternative methods for the evaluation of synchronous neoplasm[7,8]. However, because of a lack of histological confirmation, it remains unclear how accurately such imaging modalities can specifically suggest the presence of synchronous cancer. Considering the shortcomings of the modalities described above, preoperative colonoscopy through the stent may be the ideal and most reliable method for the evaluation of synchronous colon cancer. Vitale et al[9] reported the feasibility of complete preoperative colonoscopy through the expanded stent to exclude synchronous lesions. In their study, complete preoperative colonoscopy was possible in 29 out of 31 patients (93.4%). Those authors found adenoma in 8 patients (25.8%) and synchronous cancer in 3 patients (9.6%), which led to a change in the surgical plan.

In our study, complete colonic evaluation with colonoscope was possible in 30 out of 48 patients (62.5%), which was lower than the results of the previous report. However, the feasibility increased up to 42 of 48 patients (87.8%) using additional gastroscope which was similar to previous study.

Regarding the explanation for the lower rate of complete colonoscopy observed here, differences in stent might affect complete colonoscopy. Those authors used 2 types of stent (Enteral Wallstent: 6-9 cm in length and 22 mm in diameter; and Ultraflex Precision Colonic Stent: 6-12 cm in length and 25-30 mm in diameter); in contrast, in our study, to control the bias from using different types of stent, only one type was used (Hanarostent; 6-14 cm in length and 26 mm in diameter; M.I. Tech), made of Nitinol. Nitinol is an alloy of nickel and titanium that has increased flexibility, which is helpful for stenting sharply angulated regions at the cost of lesser radial force compared with stents made of other metals[11]. In contrast, a previous study by Vitale used Enteral Wallstent, which is made of Elgiloy, in 23 out of 57 patients. Differences between stents regarding material, expansion diameter, and expansion power may affect the diameter of the tunnel created by the expanded stent.

Differences in the diameter of the colonoscope may be another factor that affects complete colonoscopy. A previous study used a colonoscope with a diameter of 12.8 mm. Here, we used the colonoscope that is currently the most popular in South Korea and Japan (CF-H260AI; diameter, 13.2 mm). In another similar study, a complete preoperative colonoscopy was feasible in 40 of 45 patients (88.9%). which was higher than our results using colonoscopy only. As to different factors with our study, those authors also used relatively thin colonoscope (11.3 mm outer diameter, Evis Lucera colonovideoscope PCF-Q260JL/I; Olympus). The difference in the diameter of the colonoscope may affect success rate[12].

In terms of the factors that affected complete colonoscopy, if tumors are located near an angle, the distal and proximal sides of the stent may be located at an angle. Such a location of tumors and stents may induce angulation of the stent, with a narrower stent lumen at the waist. Therefore, it may be more difficult to pass the colonoscope in this situation. Our results revealed that the location of the tumor and stent and a narrow expansion diameter of stent are important factors that affected complete colonoscopy. But in multivariate analysis, the expansion diameter was only the significant factor affect complete colonic evaluation with colonoscope and in ROC analysis, expansion diameter over 17 mm predicted successful passage of colonoscope through the stent (sensitivity: 86.7%, specificity: 83.3%). Such a result suggests that sufficient expansion diameter is the most important factor affecting success rate and might help with the decision of how to attempt complete preoperative colonoscopy through the stent. If the expansion diameter is not sufficient, we can predict that preoperative colonoscopy is not easy to perform with colonoscope and more careful procedure and using a scope with a smaller caliber or post operative evaluation of remnant colon for synchronous colorectal neoplasm may be needed to increase the success rate and prevent complications.

As to synchronous tumors, in 18 out of 48 patients (37.5%) adenoma was detected and removed using biopsy forceps or snares. Synchronous cancers were detected in 2 patients (4.1%). The surgical resection range and plan was not changed because one was removed by endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) procedure and another located very close to primary tumor was removed by surgical resection without change of initial plan. However, it is significant to note that synchronous adenoma, which could be the cause of the development of metachronous colorectal cancer, was removed successfully before the operation. Moreover, we were able to prevent unnecessarily wide resection of the colon by complete removal of early synchronous cancers which was located at distal rectum using the ESD technique. Though location of this synchronous cancer was below of the obstruction site, it might be missed without proper colon preparation and if the synchronous early cancer is upper area of obstruction site, complete removal using the ESD technique may also be possible. This would be the most attractive feature of preoperative colonoscopy through the stent.

In terms of the safety and complications of the procedure, stent migration was not detected in any of the patients and bleeding after passage of the scope was minor and stopped spontaneously. However, colon perforation after the procedure occurred in 1 out of 48 patients (2%). In this case, the perforation point was located at the proximal end of the stent, the primary tumor was located in the rectosigmoid colon, and the inserted stent was severely angulated, with a narrow expanded lumen (The expansion diameter was 13 mm). In cases of angulated stents with a narrowed tunnel, more force is needed to pass the stent and, if a portion of the proximal end of the stent impacts the normal mucosa, perforation may occur.

The limitations of our study included the small number of cases used, which may have influenced our results. In addition, different types of stents made by other manufacturers were not evaluated, which may have affected success rates. However, the stent evaluated in this study is made of Nitinol, which is a popular material that is also used by other manufacturers. In addition to stent type, the use of small-caliber colonoscopes may affect the rate of complete colonoscopy; however, pediatric colonoscopy is may not available in many institutions. It may be hard to reach the cecum via gastroscope in cases of redundant colon and 3 of 48 patients could not reach the cecum after successful passage of scope. However, in a previous study using pediatric colonoscope, 5 of 45 patients could not reach the cecum despite successful passage of scope through the stent[12].

In conclusion, Preoperative colonoscopy through the colonic stent using only conventional colonoscope was unfavorable. However, using additional gastroscope in cases of unsuccessful passage with colonoscope, increased success rate up to 87.5%. The expansion diameter of the stent was an independent factor predicting successful preoperative colonic evaluation with colonoscope. In cases where the expansion diameter is not sufficient, we might predict unfavorable conditions regarding preoperative colonoscopy through the stent and a more careful procedure with small caliber scope such as gastroscope or pediatric colonoscope is needed.

Full preoperative colonic evaluation in patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer is important because the presence of synchronous neoplasm. Unfortunately, 10%-30% of patients with colorectal cancer present acute colonic obstruction, which precludes complete colonoscopy.

Vitale et al reported the feasibility of complete preoperative colonoscopy through the expanded stent to exclude synchronous lesions. In their study, complete preoperative colonoscopy was possible in 29 out of 31 patients (93.4%). Those authors found adenoma in 8 patients (25.8%) and synchronous cancer in 3 patients (9.6%), which led to a change in the surgical plan. Lim et al reported the feasibility of complete colonic evaluation with colonoscope was possible in 30 out of 48 patients (62.5%)

There is no study has analyzed the factors associated with the successful passage of a colonoscope through the stent and cecal intubation. This is the first study to identify the factors that affect complete colonoscopy through the stent in patients with colorectal cancer obstruction.

This study showed that the expansion diameter of the stent was an independent factor predicting successful preoperative colonic evaluation with colonoscope. Through this study, the authors might predict favorable conditions regarding preoperative colonoscopy.

The definition of complete preoperative colonoscopy in our study is successful passage of the colonoscope through the inserted colonic stent, reaching the cecum.

The authors described the efficacy of colonic stent in patients with colorectal cancer obstruction to perform preoperative colonoscopy. The aim of this study is clinically important to determine adequate treatment for such patients, however, he’d like to know more detailed data for applying these results in a clinical setting.

P- Reviewer: Kobayashi N, Takahashi T S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Adloff M, Arnaud JP, Bergamaschi R, Schloegel M. Synchronous carcinoma of the colon and rectum: prognostic and therapeutic implications. Am J Surg. 1989;157:299-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bat L, Neumann G, Shemesh E. The association of synchronous neoplasms with occluding colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:149-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cunliffe WJ, Hasleton PS, Tweedle DE, Schofield PF. Incidence of synchronous and metachronous colorectal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1984;71:941-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Isler JT, Brown PC, Lewis FG, Billingham RP. The role of preoperative colonoscopy in colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:435-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nikoloudis N, Saliangas K, Economou A, Andreadis E, Siminou S, Manna I, Georgakis K, Chrissidis T. Synchronous colorectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol. 2004;8 Suppl 1:s177-s179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Law WL, Choi HK, Lee YM, Chu KW. Palliation for advanced malignant colorectal obstruction by self-expanding metallic stents: prospective evaluation of outcomes. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:39-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Banerjee S, Van Dam J. CT colonography for colon cancer screening. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:121-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hartmann D, Bassler B, Schilling D, Pfeiffer B, Jakobs R, Eickhoff A, Riemann JF, Layer G. Incomplete conventional colonoscopy: magnetic resonance colonography in the evaluation of the proximal colon. Endoscopy. 2005;37:816-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Vitale MA, Villotti G, d’Alba L, Frontespezi S, Iacopini F, Iacopini G. Preoperative colonoscopy after self-expandable metallic stent placement in patients with acute neoplastic colon obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:814-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, Fix OK, Jacobson BC. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:620-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 930] [Cited by in RCA: 924] [Article Influence: 57.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Beck DE. Endoscopic colonic stents and dilatation. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2010;23:37-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lim SG, Lee KJ, Suh KW, Oh SY, Kim SS, Yoo JH, Wi JO. Preoperative colonoscopy for detection of synchronous neoplasms after insertion of self-expandable metal stents in occlusive colorectal cancer: comparison of covered and uncovered stents. Gut Liver. 2013;7:311-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |