Published online Jul 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9611

Revised: February 7, 2014

Accepted: March 12, 2014

Published online: July 28, 2014

Processing time: 264 Days and 10.6 Hours

AIM: To investigate the lifetime risk of development of esophageal adenocarcinoma and/or high-grade dysplasia in patients diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus.

METHODS: Data were extracted from the United Kingdom National Barrett’s Oesophagus Registry on date of diagnosis, patient age and gender of 7877 patients from who had been registered from 35 United Kingdom centers. Life expectancy was evaluated from United Kingdom National Statistics data based upon gender and age at year at diagnosis. These data were then used with published estimates of annual adenocarcinoma and high-grade dysplasia incidences from meta-analyses and large population-based studies to estimate overall lifetime risk of development of these study endpoints.

RESULTS: The mean age at diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus was 61.6 years in males and 67.3 years in females. The mean life expectancy at diagnosis was 23.1 years in males, 20.7 years in females and 22.2 years overall. Using data from published meta-analyses, the lifetime risk of development of adenocarcinoma was between 1 in 8 and 1 in 14 and the lifetime risk of high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma was 1 in 5 to 1 in 6. Using data from 3 large recent population-based cohort studies the lifetime risk of adenocarcinoma was between 1 in 10 and 1 in 37 and of the combined end-point of high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma was between 1 in 8 and 1 in 20. Age at Barrett’s esophagus diagnosis is reducing and life expectancy is increasing, which will partially counter-balance lower annual cancer incidence.

CONCLUSION: There is a significant lifetime risk of development of high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus.

Core tip: The mean life expectancy for patients at diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus is 22 years. Based on current estimates for high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma incidence, the lifetime risk of requiring an intervention for high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma development based on data from recent meta-analyses is 1 in 5 to 1 in 6 and based on data from recent population-based studies is between 1 in 8 and 1 in 20.

- Citation: Gatenby P, Caygill C, Wall C, Bhatacharjee S, Ramus J, Watson A, Winslet M. Lifetime risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett's esophagus. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(28): 9611-9617

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i28/9611.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9611

Barrett’s columnar-lined esophagus (CLE) is defined as a replacement of the epithelium of the distal esophagus from the normal squamous lining to metaplastic columnar epithelium which is thought to be secondary to prolonged gastro-esophageal reflux disease[1,2]. The presence of CLE is a marker of increased risk of development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. An analysis of a subset of 1761 patients within the United Kingdom National Barrett’s Oesophagus Registry cohort undergoing an in-depth natural history study demonstrated that the annual risk of development of adenocarcinoma was 23 cases in 3912 years of follow-up (0.59% per annum)[3], higher in those with low-grade dysplasia[4] and recent meta-analyses have estimated the annual incidence of adenocarcinoma to be 0.32% (in patients without dysplasia at index endoscopy)[5], 0.44%[6], 0.55%[7], and 0.51%[8] per annum. The majority of patients who have CLE diagnosed do not develop esophageal cancer[9], but the lifetime risk has not been well quantified. A study suggested that 10% of patients had developed high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma within 10 years of symptom onset[10]. The rate of obesity is 20%[3] and the majority of patients presented with symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux[10]. A single center study showed that in a cohort of 1150 patients with CLE followed up for more than one year, 44 died from esophageal adenocarcinoma, which accounted for 15.8% of all deaths[11]. The overall survival for this tumor remains poor (12% 5 year survival in the United Kingdom[12]). National statistics data for 2012 demonstrate that 1.9% of deaths in males and 0.8% of deaths in females were due to esophageal cancer[13]. It is postulated that there is a sequence of changes eventually leading to cancer development from metaplasia, through dysplasia to adenocarcinoma[4]. A confirmed diagnosis of high-grade dysplasia is an indication for consideration of intervention to the CLE segment (either by endoscopic therapy or esophagectomy) due to the significant possibility of the presence of an occult carcinoma and high risk of subsequent development of cancer[1]. Patients who are diagnosed with CLE may be offered surveillance in an attempt to detect dysplasia and potentially curable cancer. In an attempt to assist clinicians and patients in decision making with regard to enrollment into surveillance programs, this study models the risk of development of adenocarcinoma based upon the life expectancy of patients at diagnosis of CLE and annual risk of adenocarcinoma development using data from the United Kingdom National Barrett’s Oesophagus Registry (which has been registering cases of Barrett’s esophagus since 1996[14]), 4 recent meta-analyses of adenocarcinoma risk in Barrett’s esophagus, 3 population-based studies and Office for National Statistics data on the United Kingdom population life expectancy.

Data on patient gender, age at CLE diagnosis and date of CLE diagnosis were extracted from the United Kingdom National Barrett’s Oesophagus Registry database. Cases of CLE were included if patients were diagnosed between 1994 and 2008 from centers registering ≥ 20 patients. Patients were included if aged between 18 and 95 years at date of diagnosis. In the United Kingdom between one half[15] and two thirds[16] of patients with CLE have intestinal metaplasia detected at index endoscopy. This yielded a total of 7877 patients from 35 centers in the United Kingdom. Life expectancy was evaluated from United Kingdom National Statistics data[17] based upon gender, age at last birthday and year of diagnosis (which are available for ages up to 95 years at last birthday). Fractions of year of age at diagnosis were subtracted from the patient’s age before evaluating the life expectancy. The rate of development of cases of esophageal adenocarcinoma was then evaluated by taking the published incidence rates and subsequently estimating the total number of expected cancers and lifetime risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma for an individual. The analysis was then undertaken for the combined endpoint of high-grade dysplasia and esophageal adenocarcinoma using the published incidence of these diagnoses. Changes in age at diagnosis and life expectancy over time were examined using linear regression to allow any changes to be quantified.

Ethical permission for studies of this kind undertaken by United Kingdom BOR was granted by the London Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee on 14th March 2002 number MREC/02/26.

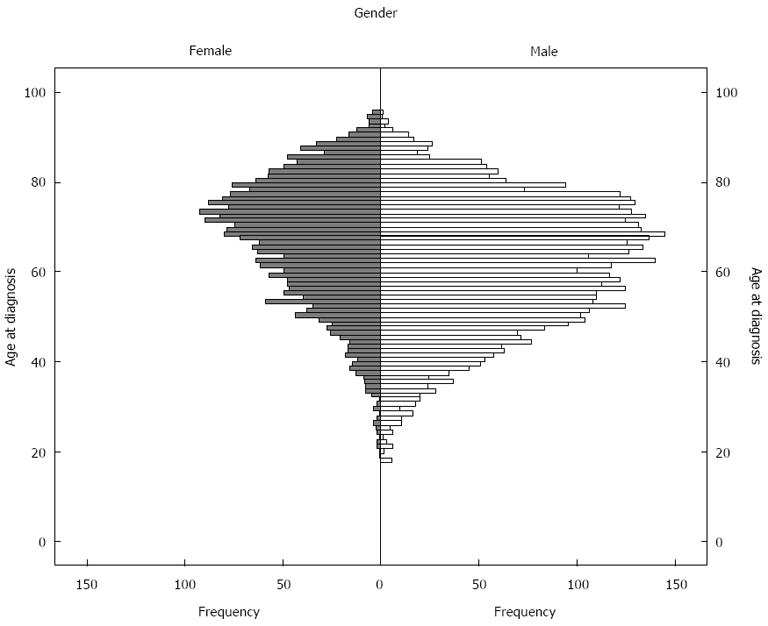

There were 2740 females (34.8% of the entire cohort) and 5137 males (65.2%) in the cohort. The mean age at diagnosis was 67.3 years in females, 61.6 years in males and 63.6 years overall. The median age at diagnosis was 69.2 years in females, 62.6 years in males and 65.0 years overall. The histogram showing the distribution of age at diagnosis is shown in Figure 1. Eight patients were excluded as they were diagnosed at > 95 years of age and life expectancy data were not available from the Office of National Statistics at these ages. The life expectancy for each individual was evaluated which demonstrated that the mean life expectancy at diagnosis for the United Kingdom age and gender-matched population was 20.7 years in females, 23.1 years in males and 22.2 years overall.

The number of cases of esophageal adenocarcinoma expected to develop during the patients’ projected lifetimes based upon the published adenocarcinoma incidence rates from meta-analyses are shown in Table 1. These equate to an individual’s lifetime odds of developing adenocarcinoma of between 1 in 8[7] to 1 in 14[5] (95%CI: 1/5-1/16).

| Ref. | Number of patients | Incidence of adenocarcinoma (n/yr follow-up) | Annual incidence of adenocarcinoma (95%CI)1 | Number of cancers expected to develop (95%CI) | Individual’s lifetime risk of adenocarcinoma (95%CI) |

| Desai et al[5] | 11434 | 186/58547 | 0.32% (0.27-0.37) | 557 (479-643) | 0.071 (0.061-0.082) |

| Yousef et al[6] | 11279 | 209/47496 | 0.44% (0.38-0.50) | 771 (670-883) | 0.098 (0.085-0.112) |

| Sikkema et al[7] | 14109 | 344/61804 | 0.56% (0.50-0.62) | 975 (874-1084) | 0.124 (0.111-0.138) |

| Thomas et al[8] | 9469 | 186/36635 | 0.51% (0.44-0.59) | 890 (766-1027) | 0.113 (0.097-0.130) |

| Gatenby et al[3] | 807 | 23/3912 | 0.59% (0.38-0.87) | 1030 (653-1546) | 0.131 (0.083-0.196) |

Since three of the four meta-analyses reported data on the incidence of high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma (which would commonly be considered an indication for an intervention on the CLE segment), the number of cases of high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma are estimated in Table 2. These equate to an individual’s lifetime odds of developing high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma to around 1 in 5 to 1 in 6.

| Ref. | Number of patients | Incidence of high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma (n/yr follow-up) | Annual incidence of high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma (95%CI)1 | Number of cases expected to develop high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma (95%CI) | Individual’s lifetime risk of developing high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma (95%CI) |

| Yousef et al[6] 2008 | 4491 | 178/22609 | 0.79% (0.67-0.91) | 1379 (1184-1598) | 0.175 (0.150-0.203) |

| Sikkema et al[7] 2010 | 4528 | 194/22559 | 0.86% (0.74-0.99) | 1506 (1302-1734) | 0.191 (0.165-0.220) |

| Thomas et al[8] 2007 | 0.9% | 1577 | 0.200 | ||

| Gatenby et al[3] 2008 | 806 | 39/3908 | 1.0% (0.71-1.4) | 1748 (1243-2390) | 0.222 (0.158-0.303) |

Linear regression analysis of age at diagnosis of CLE showed that this was reducing with time P = 0.005, B = -0.158 [95%CI: -0.267-(-0.48)], i.e., average age at Barrett’s esophagus diagnosis fell by one year for each 6.3 year increase in calendar years. Population-matched life expectancy was increasing with P < 0.001, B = 0.320 (95%CI: 0.219-0.421), i.e., life expectancy at diagnosis of Barrett’s was increasing by one year for each 3.1 increase in calendar years.

These data demonstrate that the general population’s mean life expectancy at the age at diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus is 22.2 years and is likely to continue to increase. Assuming the annual incidence of development of adenocarcinoma is 0.32% to 0.56%, this would equate to a lifetime risk of development of adenocarcinoma of between 0.071 to 0.124 (between 1 in 8 and 1 in 14) if the population with Barrett’s esophagus have the same life expectancy as the general population. If it is assumed that patients would undergo an intervention for the metaplastic segment if either high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma were detected then the lifetime risk of requiring this intervention would be 0.175 to 0.200 (between 1 in 5 and 1 in 6). There are further factors which may affect an individual’s risk.

Three of the meta-analyses examined patients with dysplasia at study entry, whereas Desai et al[5] examined cases with documented intestinal metaplasia and no dysplasia only. Yousef et al[6] demonstrated a lower risk in cases after excluding those with high grade dysplasia (or early incident cancers) at baseline. Thomas et al[8] did not demonstrate an increase in adenocarcinoma incidence in subjects with dysplasia at study entry compared to those with non-dysplastic Barrett’s epithelium.

Desai et al[5] examined the the subset of patients without dysplasia and with short segment disease and found that the annual incidence of adenocarcinoma was around half that of the whole cohort (0.19% per annum). There were similar adenocarcinoma incidence rates in long segment disease (0.67% per annum) and short segment disease (0.61% per annum)[6]. Thomas et al[8] also reported similar adenocarcinoma incidence in short and long segment disease, but a trend for lower risk in short segment disease (P = 0.25) and we have demonstrated the highest risk is in the longest segments[18].

There is controversy regarding the necessity for the demonstration of intestinal metaplasia within the columnar epithelium for the diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus and risk of development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Yousef et al[6] reported intestinal metaplasia was present in 90% (when stated). The rate quoted by Sikkema et al[7] was 78%. Desai et al[5] only examined cases with documented intestinal metaplasia and reported the lowest annual incidence rates of high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma. Previous United Kingdom studies have demonstrated that the presence or absence of intestinal metaplasia did not have an appreciable influence on adenocarcinoma risk[15,16], but a United States study has reported that no cases of dysplasia or cancer arose in subjects who did not have intestinal metaplasia detected at index endoscopy[19]. A large recent study has examined the role of intestinal metaplasia and is discussed below[20].

The meta-analyses reported similar proportions of male and female patients (with males accounting for 68%[6], 64%[7] and 62%[8]). The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in males appears to be higher than in females (1.02% per annum and 0.45% respectively reported by Yousef et al[6]) with 82% of reported cancers in the analysis of Thomas et al[8] occurring in males. The population-based cohort studies (below) have examined the role of gender further.

Thomas et al[8] showed no effect on cancer incidence dependent on age at diagnosis, but the large population-based cohorts which have suggested a significant influence of age with higher dysplasia and cancer risk at older age.

Thomas et al[8] reported no significant difference in adenocarcinoma incidence dependent upon smoking or alcohol consumption. There were no data from the meta-analyses regarding the risk of adenocarcinoma development associated with obesity, however it seems likely that there will be an increased risk in obese patients[21].

Desai et al[5] demonstrated no benefit in antireflux surgery over medical therapy, but improved reflux control is likely to reduce the risk of adenocarcinoma development[22-24].

Yousef et al[6] showed similar adenocarcinoma incidence in United Kingdom (0.70%), 0.64% in the United States and 0.56% in other European studies. Sikkema et al[7] showed annual adenocarcinoma incidences of 0.63% in the United Kingdom, 0.65% in the United States, 0.65% in Australia 0.65% and 0.56% in other European countries, but higher rates of the combined endpoint of high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma in the United Kingdom (1.30% per annum) compared to the United States (1.10% per annum) and other European countries (0.73%). Thomas et al[8] reported similar adenocarcinoma and high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma incidence in studies from United Kingdom, United States and Europe.

Thomas et al[8] demonstrated that there was a trend for a lower incidence of adenocarcinoma with time (P = 0.117). This has not been elucidated, but may be due to a combination of changes in patient factors (i.e., more females, more short segment disease, younger patients[25], improved smoking habits and alcohol consumption) and improved reflux control.

Since the publication of the meta-analyses, three further large population-based studies have been published. A further case-control study of mortality in patients with Barrett’s esophagus in the general population registered with the Clinical Practice Research Database (a United Kingdom database of primary care records) compared patients with Barrett’s esophagus to age and gender-matched control subjects[26].

Bhat et al[20] reported the results from the Northern Ireland Barrett’s esophagus Register which includes all subjects diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus in Northern Ireland between 1993 and 2005. The cohort comprised 8522 patients. Seventy-nine patients developed esophageal cancer, 16 developed gastric cardia cancer and 36 developed high-grade dysplasia after a mean of 7.0 years of follow-up (a combined incidence of 0.22% per annum). Intestinal metaplasia was present in 46% of patients and these patients had a higher risk of adenocarcinoma (0.38% per year compared to 0.07% in patients without intestinal metaplasia). The adenocarcinoma incidence was 0.28% in males and 0.13% in females. Patients with low-grade dysplasia had a higher annual incidence of adenocarcinoma development (1.40% per annum compared to 0.17% in those with no dysplasia). If the incidence rate from this study were used then the predicted lifetime risk of development of adenocarcinoma in our cohort was 5.8% in males (1 in 17) and 3.0% in females (1 in 33). The lifetime risk for the whole cohort of development of high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma was 4.89% (1 in 20).

de Jonge et al[27] reported the results from the Dutch nationwide pathology registry which contained data on 16333 patients without prevalent cancer and at least one year of follow-up. About 9.8% had low-grade dysplasia at baseline. Total follow-up was 78105 patient-years. The annual incidence of adenocarcinoma was 0.43% and of high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma was 0.58%. They noted that among the patients who developed high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma the proportion of females increased with older age. Adenocarcinoma incidence was higher in males compared to females, at older age at diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus and in patients with dysplasia at baseline. Cases of high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma continued throughout the follow-up period beyond 10 years from diagnosis. Using the incidence rates from this paper and applying them to our data, the lifetime risk of development of adenocarcinoma for the cohort was 9.6% (1 in 10) and lifetime risk of developing high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma was 12.9% (1 in 8).

Hvid-Jensen et al[28] examined the Danish Pathology Registry and the Danish Cancer Registry during the period from 1992 to 2009. Their cohort comprised 11028 patients with Barrett’s esophagus followed up for a median of 5.2 years. Sixty-six incident adenocarcinomas were detected, yielding the lowest reported incidence rate for adenocarcinoma of 0.12% per annum. Patients with low-grade dysplasia at the index endoscopy had an incidence rate for adenocarcinoma of 0.51% per annum and those with no dysplasia at diagnosis had an annual adenocarcinoma risk of 0.10%. Using this incidence, the lifetime risk for an individual patient in the United Kingdom cohort would be 2.67% (1 in 37), but this paper also noted that adenocarcinoma incidence increased with older patient age.

Sikkema et al[7] reported the number of incident cases of esophageal adenocarcinoma and mortality outcomes from 17 studies. There were 131 cases of incident esophageal adenocarcinoma [of whom 75 (7%) were reported to have died from their disease) and 992 patients had died from other causes (cardiovascular disease (35%), followed by respiratory disease (20%), other malignancies (16%), unrelated gastrointestinal conditions (4%), other causes (4%)]. Desai et al[5] reported the number of incident cases of esophageal adenocarcinoma and mortality outcomes from 16 studies. There were 56 cases of incident esophageal adenocarcinoma and 693 patients had died of other causes. For these patients, whose final outcome could be determined, 11.7% had developed adenocarcinoma (1 in 8.5) from the data from Sikkema et al[7] and 7.5% (1 in 13) from the data from Desai et al[5]. These data support the lifetime adenocarcinoma risk calculated in this paper.

Solaymani-Dodaran et al[26] demonstrated that overall mortality in patients with Barrett’s esophagus was 21% higher than in control subjects from the general population (with higher rates of neoplastic, respiratory and gastrointestinal causes of death). The hazards ratio for patients with Barrett’s esophagus to die due to esophageal cancer compared to control subjects was 12.8. In this study 4.5% of the Barrett’s esophagus cohort and 1.1% of the control cohort died due to esophageal cancer. This compares to 1.4% of all deaths in England and Wales in 2012 and more than 2% of all deaths in those aged 45-74 being secondary to esophageal cancer[13].

There are three assumptions made in the methodology which are potential weaknesses: (1) patients with Barrett’s esophagus have similar life expectancy to the general population; (2) adenocarcinoma risk for all individual patients after Barrett’s esophagus diagnosis is equal and remains constant; and (3) adenocarcinoma incidence in Barrett’s esophagus is not significantly changing with time.

There is limited evidence from the study by Solaymani-Dodaran et al[26] that the mortality in subjects with Barrett’s esophagus is higher than that of the general population, but this has not been more widely demonstrated and in the single center United Kingdom study the excess mortality was due to cases of esophageal adenocarcinoma[11].

The second assumption is less robust. Firstly, there are a number of patient factors (see above) which are likely to affect an individual’s risk and secondly, the assumption that the adenocarcinoma risk does not vary as a patient ages during follow-up does not have a strong basis with suggestion from two of the population-based studies that cancer risk increases with age[27,28]. Furthermore, the published studies tend to have follow-up periods of less than half of the projected 22 years of life for a typical patient and far shorter than for those diagnosed at a young age. It is possible that exclusion of older patients from surveillance programs may reduce the perceived annual incidence of esophageal cancer, but not the lifetime risk and United Kingdom cancer registry data demonstrate that the annual incidence of esophageal cancer increases with age and more than half of esophageal cancers arise in males age older than 70 and females age 75[29,30].

Finally, the assumption that adenocarcinoma incidence is not changing is likely to be challenged in future, but whether this is due to differences in surveillance practices or a change in the biology of Barrett’s esophagus is not clear.

This is the first study to address this important issue with large numbers and calculations based on the best available published evidence and should guide clinicians and patients in their interpretation of the overall risk of cancer (and high-grade dysplasia) development. Further studies to examine subgroup risk will help tailor targeted surveillance to those who would benefit most from it whilst reassuring those at low risk and optimize resource use.

There has been extensive publication on annual risk of cancer in Barrett’s esophagus including studies examining groups at higher and lower risk, but the overall lifetime risk for individuals has not been well-examined.

Recent meta-analyses have estimated annual risk of adenocarcinoma to be between 0.32% and 0.56% per annum and of high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma to be between 0.79% and 0.9% per annum. Population-based studies have reported adenocarcinoma incidence of 0.12%-0.43% and of high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma of 0.19% to 0.58% per annum.

This article has estimated the lifetime risk of development of adenocarcinoma to be between 7 and 12% (1 in 8 to 1 in 14) and the risk of high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma to be between 17 and 20% (1 in 5 to 1 in 6) from the data from meta-analyses.

These data will assist clinicians and patients in their decisions to enrol in surveillance programmes.

Barrett’s esophagus describes a change in the lining of the lower esophagus secondary to prolonged gastro-esophageal reflux and has a risk of development of esophageal cancer, specifically adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. High-grade dysplasia describes the immediate pre-cancerous changes which may also harbour an occult cancer and are generally viewed as an indication for an intervention to the esophagus to reduce the risk of developing more extensive esophageal cancer, which cannot be treated with curative intent.

This Paper confirms and provides additional evidence supporting the low dysplasia/cancer progression rates in individuals with Barrett’s esophagus. The study is well conducted.

P- Reviewer: Cao W, Guda K, Rosztoczy A S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Watson A, Heading R, Shepherd N. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s columnar-lined oesophagus: A Report of the Working Party of the British Society of Gastroenterology. Available from: http://www.bsg.org.uk/clinical-guidelines/general/guidelines-by-date.html. |

| 2. | Rosztóczy A, Izbéki F, Róka R, Németh I, Gecse K, Vadászi K, Kádár J, Vetró E, Tiszlavicz L, Wittmann T. The evaluation of oesophageal function in patients with different types of oesophageal metaplasia. Digestion. 2011;84:273-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gatenby PA, Caygill CP, Ramus JR, Charlett A, Watson A. Barrett’s columnar-lined oesophagus: demographic and lifestyle associations and adenocarcinoma risk. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:1175-1185. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Gatenby P, Ramus J, Caygill C, Shepherd N, Winslet M, Watson A. Routinely diagnosed low-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s oesophagus: a population-based study of natural history. Histopathology. 2009;54:814-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Desai TK, Krishnan K, Samala N, Singh J, Cluley J, Perla S, Howden CW. The incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in non-dysplastic Barrett’s oesophagus: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2012;61:970-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 423] [Cited by in RCA: 414] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yousef F, Cardwell C, Cantwell MM, Galway K, Johnston BT, Murray L. The incidence of esophageal cancer and high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:237-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 287] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sikkema M, de Jonge PJ, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ. Risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma and mortality in patients with Barrett’s esophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:235-44; quiz e32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Thomas T, Abrams KR, De Caestecker JS, Robinson RJ. Meta analysis: Cancer risk in Barrett’s oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1465-1477. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Gatenby PA, Ramus JR, Caygill CP, Fitzgerald RC, Charlett A, Winslet MC, Watson A. The influence of symptom type and duration on the fate of the metaplastic columnar-lined Barrett’s oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:1096-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Caygill CP, Royston C, Charlett A, Wall CM, Gatenby PA, Ramus JR, Watson A, Winslet M, Bardhan KD. Mortality in Barrett’s esophagus: three decades of experience at a single center. Endoscopy. 2012;44:892-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Office for National Statistics. Cancer survival in England: one-year and five-year survival for 21 common cancers, by sex and age. Available from: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/taxonomy/index.html?nscl=Cancer Survival. |

| 13. | Office for National Statistics. Death Registrations Summary Tables, England and Wales, 2012. Available from: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/vsob1/death-reg-sum-tables/2012/index.html. |

| 14. | Caygill CP, Reed PI, Watson A, Hill MJ. The UK National Barrett’s Oesophagus Registry (UKBOR): aims and progress. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2001;10:97-99. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Kelty CJ, Gough MD, Van Wyk Q, Stephenson TJ, Ackroyd R. Barrett’s oesophagus: intestinal metaplasia is not essential for cancer risk. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:1271-1274. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Gatenby PA, Ramus JR, Caygill CP, Shepherd NA, Watson A. Relevance of the detection of intestinal metaplasia in non-dysplastic columnar-lined oesophagus. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:524-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Office of National Statistics. 2008-based period and cohort life expectancy tables. Available from: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/lifetables/period-and-cohort-life-expectancy-tables/2008-based/index.html. |

| 18. | Gatenby PA, Caygill CP, Ramus JR, Charlett A, Fitzgerald RC, Watson A. Short segment columnar-lined oesophagus: an underestimated cancer risk? A large cohort study of the relationship between Barrett’s columnar-lined oesophagus segment length and adenocarcinoma risk. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:969-975. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Westerhoff M, Hovan L, Lee C, Hart J. Effects of dropping the requirement for goblet cells from the diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1232-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bhat S, Coleman HG, Yousef F, Johnston BT, McManus DT, Gavin AT, Murray LJ. Risk of malignant progression in Barrett’s esophagus patients: results from a large population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1049-1057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 573] [Cited by in RCA: 517] [Article Influence: 36.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Anderson LA, Watson RG, Murphy SJ, Johnston BT, Comber H, Mc Guigan J, Reynolds JV, Murray LJ. Risk factors for Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma: results from the FINBAR study. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1585-1594. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Peters FT, Ganesh S, Kuipers EJ, Sluiter WJ, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Lamers CB, Kleibeuker JH. Endoscopic regression of Barrett’s oesophagus during omeprazole treatment; a randomised double blind study. Gut. 1999;45:489-494. [PubMed] |

| 23. | El-Serag HB, Aguirre TV, Davis S, Kuebeler M, Bhattacharyya A, Sampliner RE. Proton pump inhibitors are associated with reduced incidence of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1877-1883. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Hillman LC, Chiragakis L, Shadbolt B, Kaye GL, Clarke AC. Proton-pump inhibitor therapy and the development of dysplasia in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus. Med J Aust. 2004;180:387-391. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Wall CM, Charlett A, Caygill CP, Gatenby PA, Ramus JR, Winslet MC, Watson A. Are newly diagnosed columnar-lined oesophagus patients getting younger? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1127-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Solaymani-Dodaran M, Card TR, West J. Cause-specific mortality of people with Barrett’s esophagus compared with the general population: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1375-183, 1383.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | de Jonge PJ, van Blankenstein M, Looman CW, Casparie MK, Meijer GA, Kuipers EJ. Risk of malignant progression in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus: a Dutch nationwide cohort study. Gut. 2010;59:1030-1036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hvid-Jensen F, Pedersen L, Drewes AM, Sørensen HT, Funch-Jensen P. Incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1375-1383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 985] [Cited by in RCA: 980] [Article Influence: 70.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Office for National Statistics. Cancer Statistics Registrations, England Series MB1, No.42, 2011. Available from: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/vsob1/cancer-statistics-registrations--england--series-mb1-/no--42--2011/index.html. |

| 30. | Gatenby PA, Hainsworth A, Caygill C, Watson A, Winslet M. Projections for oesophageal cancer incidence in England to 2033. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2011;20:283-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |