Published online Jul 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i25.8304

Revised: February 9, 2014

Accepted: March 19, 2014

Published online: July 7, 2014

Processing time: 198 Days and 13.3 Hours

A variety of clinical manifestations are associated directly or indirectly with tuberculosis. Among them, haematological abnormalities can be found in both the pulmonary and extrapulmonary forms of the disease. We report a case of immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) associated with intestinal tuberculosis in a liver transplant recipient. The initial management of thrombocytopenia, with steroids and intravenous immunoglobulin, was not successful, and the lack of tuberculosis symptoms hampered a proper diagnostic evaluation. After the diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis and the initiation of specific treatment, a progressive increase in the platelet count was observed. The mechanism of ITP associated with tuberculosis has not yet been well elucidated, but this condition should be considered in cases of ITP that are unresponsive to steroids and intravenous immunoglobulin, especially in immunocompromised patients and those from endemic areas.

Core tip: This is the report of a rare case of immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) associated with intestinal tuberculosis. In approximately 50% of ITP cases, the aetiology is not identifiable. The most common secondary causes are systemic lupus erythematosus, lymphoproliferative diseases, HIV infection and drugs. It is difficult to make a diagnosis of tuberculosis-related ITP, and timely therapy is important. This association should be considered in cases of ITP that are unresponsive to steroids and intravenous immunoglobulin, especially in immunocompromised patients and those from endemic areas.

- Citation: Lugao RDS, Motta MP, Azevedo MFC, Lima RGR, Abrantes FA, Abdala E, Carrilho FJ, Mazo DFC. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura induced by intestinal tuberculosis in a liver transplant recipient. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(25): 8304-8308

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i25/8304.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i25.8304

Despite its description over a century ago by H.H. Robert Koch, tuberculosis remains a worldwide health problem, primarily in developing countries. A variety of clinical manifestations are associated directly or indirectly with tubercle bacillus. Among them, haematological abnormalities can be found in both the pulmonary and extrapulmonary forms of the disease[1]. Isolated secondary thrombocytopenia is an unusual complication that occurs primarily via a non-immune mechanism (bone marrow infiltration by granulomas)[1,2]. Tuberculosis-induced immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is rare, with few cases reported in the literature[3-5] and only one case reported in the context of intestinal tuberculosis[6]. Here, we describe a case of ITP associated with intestinal tuberculosis.

A 69-year-old male who underwent a liver transplantation 11 years ago due to alcoholic cirrhosis and who was using tacrolimus (1.5 mg/d) for immunosuppression (serum level of 2.7 ng/mL) came to his outpatient follow-up visit complaining of malaise, decreased appetite and a weight loss of 3 kg in the last 3 mo. He denied fever, respiratory symptoms, changes in bowel habits or other complaints. On physical examination, pale mucosa, bruises and painless purpuric lesions on the lower limbs were noted. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable. Laboratory tests showed pancytopenia (haemoglobin level: 9.0 g/dL, platelet count of 1300/mm3, leukocytes 2230/mm3) and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 72 mm. The coagulation tests were normal and without laboratory evidence of haemolysis. The serum antinuclear and anti-DNA antibodies were negative, as was the viral serology [HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for Cytomegalovirus and B19 parvovirus]. The serum complement levels, immunoglobulin, iron, folic acid and vitamin B12 were within the normal range. The myelogram showed a normocellular bone marrow with normal maturation, and PCR for M. tuberculosis and other agents (Cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus and B19 parvovirus) showed negative results.

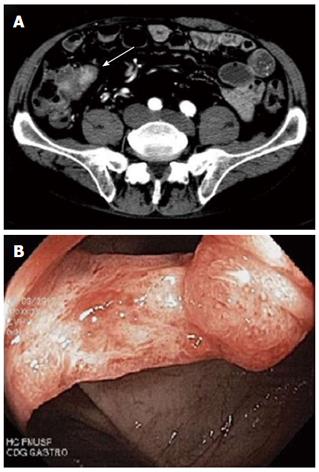

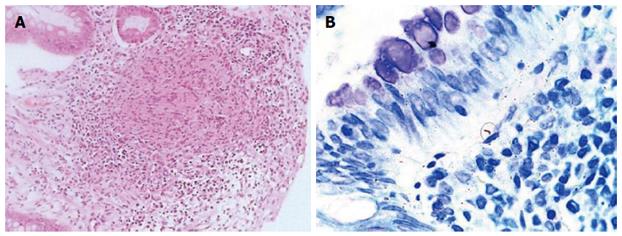

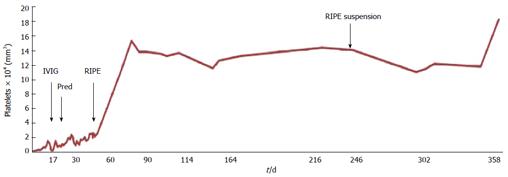

The bone marrow biopsy was normocellular for the patient’s age, with erythrocytic hyperplasia and granulocytic hypoplasia. Megakaryocytes were normal in number and morphology, and no granulomas were found. The tacrolimus was switched to cyclosporine, but marked thrombocytopenia persisted. During hospitalisation, the thrombocytopenia worsened despite repeated platelet transfusions. This clinical picture, in addition to the finding of positive anti-platelet antibodies, led to the diagnosis of ITP. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was started (1 mg/kg per day), followed by prednisone 60 mg/d by mouth for four weeks without satisfactory results. The platelet count did not surpass 27000/mm3. Because the patient was unresponsive to standard ITP treatment, thorax and abdominal computed tomography were performed to rule out other potential etiologies. A slight thickening of a small segment of the terminal ileum was detected (Figure 1A). A colonoscopy revealed an oedematous and friable ileocaecal valve with an infiltrative appearance (Figure 1B). A histological evaluation indicated a chronic inflammatory process with intense activity and a granuloma (Figure 2A). Alcohol-acid resistant bacilli were found in the histological specimen (Figure 2B). Therefore, anti-tuberculosis therapy was initiated as follows: rifampicin 600 mg/d, isoniazid 300 mg/d, pyrazinamide 1600 mg/d and ethambutol 1200 mg/d, along with prednisone tapering. After the initiation of the tuberculosis treatment, there was a progressive increase in the platelet count, which reached normal levels within a month (Figure 3). The cyclosporine dosage was required to be increased to maintain optimal serum levels due to interactions with anti-tuberculosis drugs and was replaced with tacrolimus in the following month. The anaemia and leukopenia improved until normalisation after three months (haemoglobin level: 13.4 g/dL, leukocytes 4030/mm3).

Several hematologic manifestations, such as anaemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, thrombocytosis, leukemoid reaction and pancytopenia, have been described in patients with tuberculosis[1,2]. There are few reports of ITP being associated with tuberculosis[4]. In an evaluation of 846 patients, al-Majed et al[7] found an association with ITP in only 1% of cases. These cases are, in order of increasing frequency, associated with pulmonary tuberculosis, lymphadenitis and miliary tuberculosis[2,5]. Thus far, to our knowledge, there is only one previous report of ITP associated with intestinal tuberculosis; however, this association was in the context of myelodysplasia and chronic hepatitis C[6].

Intestinal tuberculosis corresponds to the sixth major site of extrapulmonary tuberculosis involvement[8] and is associated with concurrent active pulmonary tuberculosis in less than 30% of cases[9]. The most commonly involved region is ileocaecal because of the abundance of lymphoid tissue, although any part of the digestive tract may be affected[9]. The clinical presentation is generally nonspecific, in some cases subclinical, and depends upon the site of involvement[8,10]. The endoscopic appearance can be ulcerative, ulcerative-hypertrophic, hypertrophic or fibrotic[8]. The differential diagnosis is broad and should include mainly Crohn’s disease, lymphoma, bacterial and viral infections (e.g., Yersinia enterocolitica) and drugs. Intestinal tuberculosis is a rare condition, but it must be considered, especially in endemic countries and at-risk populations (e.g., immunocompromised), as in this case.

In ITP, the formation of antiplatelet antibodies promotes accelerated platelet destruction[11,12]. The two main diagnostic criteria for ITP are isolated thrombocytopenia with normal peripheral blood smear and the exclusion of other causes of thrombocytopenia[12,13]. In this report, pancytopenia, rather than isolated thrombocytopenia, required an extensive workup for haematological diseases. The exclusion of other causes of thrombocytopenia (including the use of tacrolimus), associated with a worsening in platelet count after repeated transfusions, suggested that an immune mechanism was involved. ITP is a diagnosis of exclusion, and routine testing for platelet antibodies is not recommended; however, the finding of positive antiplatelet antibodies may sometimes be useful in confirming an immune cause (although these antibodies are not specific for ITP)[14]. Positive antiplatelet antibodies can be detected in other conditions, such as liver cirrhosis and chronic thyroiditis[5]. Some authors have found that the identification of platelet-associated antibodies has prognostic significance in ITP[14].

In approximately 50% of ITP cases, the aetiology is not identifiable. The most common secondary causes are systemic lupus erythematosus, lymphoproliferative diseases (especially chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and Hodgkin’s lymphoma), HIV infection and drugs[13,15]. The mechanism underlying the association of ITP with tuberculosis is not well elucidated, and further studies are needed to better understand its pathophysiology. Some authors suggest that M. tuberculosis is able to stimulate autologous lymphocytes against platelets and promote the production of antiplatelet antibodies[2].

Corticosteroids are the treatment of choice for ITP in adults. In cases that are responsive to treatment, there is usually an increase in the platelet count after one week of therapy, and a peak platelet count occurs in two to four weeks. Human IVIG is another treatment option that is capable of augmenting the platelet count more rapidly than steroids[12,15,16]. In cases of secondary ITP, thrombocytopenia can often be resolved by treating the underlying disorder[15]. Therefore, in cases of tuberculosis associated with ITP, the most important therapy is anti-tuberculosis treatment. This treatment regimen can be combined with corticosteroids and/or human IVIG according to the degree of thrombocytopenia or the presence of bleeding[5,17]. IVIG is the treatment of choice due to the potential risk of immunosuppression with steroids and the subsequent exacerbation of tuberculosis[3,5]. Immunomodulatory therapy alone does not appear to promote a satisfactory response, which supports tuberculosis as the underlying cause of ITP in these case reports. In published cases of ITP that is associated with tuberculosis, most authors used anti-tuberculosis drugs combined with steroids or IVIG[3-5,13,18-20]. In our case, the resolution of thrombocytopenia was obtained with anti-tuberculosis drugs alone. The improvement of haemoglobin and leukocyte levels obtained with tuberculosis treatment suggests a causal relationship with tuberculosis itself.

In most reports of ITP-related tuberculosis, there is an initial difficulty in identifying tuberculosis as the cause of thrombocytopenia, and our case was not different. The subclinical presentation of intestinal tuberculosis led to a delayed diagnosis. The association with tuberculosis should be considered in cases of ITP that are unresponsive to steroids and IVIG. This association should be considered even in the absence of a suggestive clinical picture and especially in immunocompromised patients and those from endemic areas.

A 69-year-old liver-transplanted male with malaise, decreased appetite and weight loss over the last 3 mo.

Pale mucosa, bruises and painless purpuric lesions on the lower limbs with marked thrombocytopenia.

Anaemia and thrombocytopenia secondary to immunosuppression, infectious agents and lymphoproliferative diseases.

Haemoglobin level: 9.0 g/dL, platelet count of 1300/mm3, (leukocytes 2230/mm3) and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 72 mm; positivity for anti-platelet antibodies.

Abdominal computed tomography with a slight thickening of a small segment of the terminal ileum; colonoscopy with oedematous and a friable ileocaecal valve with an infiltrative appearance.

Chronic inflammatory process with intense activity and a granuloma; alcohol-acid-resistant bacilli were found in the specimen.

The patient was treated with rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol.

Tuberculosis-induced immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is rare, with few cases reported in the literature.

This case report demonstrates the rare association of ITP with subclinical intestinal tuberculosis, which requires a high index of suspicion, especially in immunocompromised patients and those from endemic areas.

This is a rare case of tuberculosis-induced ITP. Despite its rarity and difficulty of diagnosis, timely therapy is important.

P- Reviewers: Hartl JV, Rodriguez-Peralvarez ML, Tomohide H S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Glasser RM, Walker RI, Herion JC. The significance of hematologic abnormalities in patients with tuberculosis. Arch Intern Med. 1970;125:691-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jurak SS, Aster R, Sawaf H. Immune thrombocytopenia associated with tuberculosis. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1983;22:318-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ursavas A, Ediger D, Ali R, Köprücüoglu D, Bahçetepe D, Kocamaz G, Coskun F, Ege E. Immune thrombocytopenia associated with pulmonary tuberculosis. J Infect Chemother. 2010;16:42-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kalra A, Kalra A, Palaniswamy C, Vikram N, Khilnani GC, Sood R. Immune thrombocytopenia in a challenging case of disseminated tuberculosis: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Med. 2010;2010:pii: 946278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tsuro K, Kojima H, Mitoro A, Yoshiji H, Fujimoto M, Uemura M, Masahide Y, Fukui H. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura associated with pulmonary tuberculosis. Intern Med. 2006;45:739-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Olave MT, Iturbe T, Fuertes MA, Palomera L. [Autoimmune thrombocytopenia in the clinical context of myelodysplasia with chromosome 7 deletion, intestinal tuberculosis, and chronic hepatitis caused by hepatitis C virus]. Sangre (Barc). 1999;44:495-496. [PubMed] |

| 7. | al-Majed SA, al-Momen AK, al-Kassimi FA, al-Zeer A, Kambal AM, Baaqil H. Tuberculosis presenting as immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Acta Haematol. 1995;94:135-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Donoghue HD, Holton J. Intestinal tuberculosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22:490-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Almadi MA, Ghosh S, Aljebreen AM. Differentiating intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease: a diagnostic challenge. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1003-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sato S, Yao K, Yao T, Schlemper RJ, Matsui T, Sakurai T, Iwashita A. Colonoscopy in the diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis in asymptomatic patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:362-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Psaila B, Bussel JB. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2007;21:743-759, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rodeghiero F, Stasi R, Gernsheimer T, Michel M, Provan D, Arnold DM, Bussel JB, Cines DB, Chong BH, Cooper N. Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: report from an international working group. Blood. 2009;113:2386-2393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1569] [Cited by in RCA: 1841] [Article Influence: 108.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ghobrial MW, Albornoz MA. Immune thrombocytopenia: a rare presenting manifestation of tuberculosis. Am J Hematol. 2001;67:139-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Heikal NM, Smock KJ. Laboratory testing for platelet antibodies. Am J Hematol. 2013;88:818-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bussel JB. Therapeutic approaches to secondary immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Semin Hematol. 2009;46:S44-S58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | George JN. Sequence of treatments for adults with primary immune thrombocytopenia. Am J Hematol. 2012;87 Suppl 1:S12-S15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ozkalemkas F, Ali R, Ozkan A, Ozcelik T, Ozkocaman V, Kunt-Uzaslan E, Bahadir-Erdogan B, Akalin H. Tuberculosis presenting as immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2004;3:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Boots RJ, Roberts AW, McEvoy D. Immune thrombocytopenia complicating pulmonary tuberculosis: case report and investigation of mechanisms. Thorax. 1992;47:396-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hernández-Maraver D, Peláez J, Pinilla J, Navarro FH. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura due to disseminated tuberculosis. Acta Haematol. 1996;96:266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tabarsi P, Merza MA, Marjani M. Active pulmonary tuberculosis manifesting with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a rare presentation. Braz J Infect Dis. 2010;14:639-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |