Published online Jul 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i25.8195

Revised: January 16, 2014

Accepted: April 5, 2014

Published online: July 7, 2014

Processing time: 245 Days and 22.9 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the predictive effect of baseline hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) on response to pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN)-α2b in hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients.

METHODS: This retrospective analysis compared the treatment efficacy of PEG-IFN-α2b alone in 55 HBeAg-positive CHB patients with different baseline HBsAg levels. Serum HBV DNA load was measured at baseline, and at 12, 24 and 48 wk of therapy. Virological response was defined as HBV DNA < 1000 IU/mL. Serum HBsAg titers were quantitatively assayed at baseline, and at 12 and 24 wk.

RESULTS: Eighteen patients had baseline HBsAg > 20 000 IU/mL, 26 patients had 1500-20000 IU/mL, and 11 patients had < 1500 IU/mL. Three (16.7%), 11 (42.3%) and seven (63.6%) patients in each group achieved a virological response at week 48, with a significant difference between groups with baseline HBsAg levels > 20000 or < 20000 IU/mL (P = 0.02). Thirteen patients had an HBsAg decline > 0.5 log10 and 30 patients < 0.5 log10 at week 12; and 6 (46.2%) and 10 (33.3%) in each group achieved virological response at week 48, with no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.502). Eighteen patients had an HBsAg decline > 1.0 log10 and 30 patients < 1.0 log10 at week 24, and 8 (44.4%) and 11 (36.7%) achieved a virological response at week 48, with no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.762). None of the 16 patients with HBsAg > 20000 IU/mL at week 24 achieved a virological response at week 48.

CONCLUSION: Baseline HBsAg level in combination with HBV DNA may become an effective predictor for guiding optimal therapy with PEG-IFN-α2b against HBeAg-positive CHB.

Core tip: The response to antiviral therapy in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients varies significantly among individuals. This retrospective study of 55 patients evaluated the predictive effect of baseline hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) on virological response in HBeAg-positive CHB patients treated with pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN)-α2b. The results suggest that baseline HBsAg level in combination with HBV DNA quantitative values may become an effective predictor for guiding optimal therapy with PEG-IFN-α2b against HBeAg-positive CHB.

- Citation: Chen GY, Zhu MF, Zheng DL, Bao YT, Wang J, Zhou X, Lou GQ. Baseline HBsAg predicts response to pegylated interferon-α2b in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(25): 8195-8200

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i25/8195.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i25.8195

In Asia, 5%-10% of adults and up to 90% of infants among 50 million new cases of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection will become chronically infected annually, which is the leading cause of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma[1]. Ideally, these chronic carriers should be identified and medical interventions implemented to reduce the risk of premature death. Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is a dynamic state of interactions between HBV, hepatocytes, and the immune system. Therefore, the primary aim of therapy is to eliminate or permanently suppress HBV to reduce hepatitis activity and thereby reduce the risk or slow the progression of liver disease[2]. The International Association for the Study of Liver Diseases provides guidelines to recognize patients who need antiviral therapy and regularly updates its guidance related to the sustained response to interferon (IFN), which is influenced by IL28B genotype, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) level during therapy, and HBV DNA[3]. Recent studies have indicated that HBsAg quantification might be a useful complement to HBV DNA quantification for clinical assessment and treatment monitoring in patients with CHB[4-6]. The quantitative measurement of HBsAg in combination with HBV DNA detection may aid clinicians in creating a specific therapeutic regime for individual patients.

The present study aimed to explore the predictive value of the baseline HBsAg level on therapeutic effects of pegylated IFN (PEG-IFN)-α2b in patients with CHB positive for hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg).

A total of 55 patients, 35 male and 20 female, aged 18-52 years (average: 39 ± 10 years), who were hospitalized from June 2011 to June 2012, were included in this retrospective study. Their diagnosis met the CHB diagnosis standard in the Chronic Hepatitis B Prevention Guide 2010[7]. After hospitalization, the patients underwent routine examination including routine blood tests, blood biochemistry, virological indicators, type B ultrasonic inspection of the liver, gallbladder and spleen to exclude patients co-infected with other types of hepatitis virus or cirrhosis, and previous history of antiviral therapy. All patients underwent liver puncture biopsy; the sections were inspected by an experienced pathologist. They had received antiviral therapy for the first time and expected to finish therapy in a short period. Their alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concentration was 2-10 times higher than the upper limit of normal, or the liver tissue inflammation was higher than grade 2. They all selected a 48-wk course of antiviral monotherapy with PEG-IFN-α-2b (subcutaneous injection, 1.5 μg/kg weekly). Virological response was defined as HBV DNA < 1000 IU/mL at the end of therapy.

Two milliliters of venous blood from a fasting patient was collected. After separation, 0.2 mL serum was stored at -80 °C. Serum HBV DNA was determined using TaqMan fluorescent quantitative polymerase chain reaction. The primers, probes and materials were purchased from Hangzhou Bo Saiji Diagnostic Technology Co. Ltd. (Hangzhou, China). The sensitivity was 1000 IU/mL and was used predominantly for the detection of HBV DNA quantitative values at baseline and during the period of therapy (at 12, 24 and 48 wk). The dilution values of baseline HBsAg, at week 12 and 24 were quantitatively measured using the Architect HBsAg QT assay (Abbott, Chicago, IL, United States).

SPSS version 16.0 statistical software was used. The difference in baseline HBsAg among the groups was analyzed by non-parametric χ2 test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

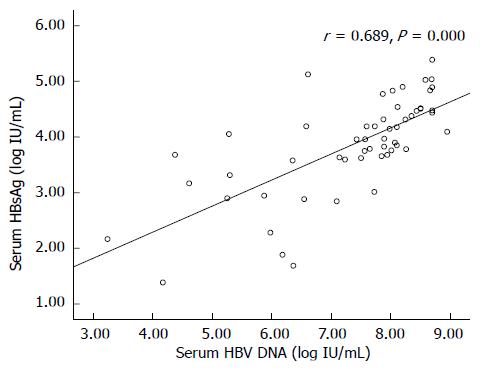

Quantitative measurement of the baseline HBsAg dilution value was performed in all 55 patients. Baseline HBsAg in 18 patients was > 20000 IU/mL (32.7%) and in 11 patients it was < 1500 IU/mL (20%). HBsAg (log10 IU/mL) had a significant positive correlation with HBV DNA level (log10 IU/mL) (r = 0.689, P = 0.000). Baseline HBsAg and HBV DNA levels are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1.

| Baseline HBsAg (IU/mL) | Baseline HBV DNA (log10) | Case number (constituent ratio, %) |

| > 20000 | 8.14 ± 0.87 | 18 (32.7) |

| 1500-20000 | 7.39 ± 1.01 | 26 (47.3) |

| < 1500 | 5.89 ± 1.07 | 11 (20.0) |

After treatment with PEG-IFN-α2b monotherapy for 48 wk, among the 18 patients with baseline HBsAg > 20000 IU/mL, three patients showed HBV DNA negative conversion and HBeAg seroconversion. Among the 26 patients with baseline HBsAg 1500-20000 IU/mL, 11 patients showed HBV DNA negative conversion and HBeAg seroconversion. Among the 11 patients with baseline HBsAg < 1500 IU/mL, seven patients showed HBV DNA negative conversion and HBeAg seroconversion. The difference in the virological response rate between patients with HBsAg > 20000 IU/mL and < 20000 IU/mL was statistically significant. The detailed data are shown in Table 2.

| Baseline HBsAg (IU/mL) | Virological response rate (%) |

| > 20000 | 3/18 (16.7) |

| 1500-20000 | 11/26 (42.3) |

| < 1500 | 7/11 (63.6) |

Among the 55 patients receiving PEG-IFN-α2b therapy, 43 had their HBsAg dilution value measured at three time points (before therapy, and after 12 and 48 wk of therapy). At week 12 of therapy, 13 patients showed a decline in HBsAg values of > 0.5 log10, and at week 48, 6 (46.15%) of these patients had acquired HBV DNA negative conversion. At week 12, 30 patients showed a decline in HBsAg values < 0.5 log10, and at 48 wk, 10 (33.33%) of these patients had acquired HBV DNA negative conversion. There was no significant difference in the HBV DNA negative conversion rate between patients in the groups with a decline of HBsAg > 0.5 log10 or < 0.5 log10 (P = 0.502).

Among the 55 patients receiving PEG-IFN-α2b therapy, 48 had their HBsAg dilution value measured at three time points (before therapy, and after 24 and 48 wk of therapy). At week 24, 18 patients had a reduction in HBsAg values > 1.0 log10, and at week 48, eight (44.44%) of these patients acquired HBV DNA negative conversion. At week 24, 30 patients had HBsAg value decline < 1.0 log10, and at week 48, 11 (36.67%) of these patients acquired HBV DNA negative conversion. There was no significant difference in the HBV DNA negative conversion rate between patients in the groups with a decline of HBsAg value > 1.0 log10 or < 1.0 log10 (P = 0.762).

After treatment with PEG-IFN-α2b for 24 wk, 16 patients had HBsAg values > 20000 IU/mL. After 48 wk of treatment with PEG-IFN-α2b, no patient had HBV DNA negative conversion. The predictive accuracy for virological response at week 48 reached 100% when HBsAg was > 20000 IU/mL at week 24.

The detection of HBsAg in serum happened about 40 years earlier than the discovery of HBV and retains its importance in CHB diagnosis today[8,9]. HBsAg seroclearance is considered to be the closest thing to a cure for CHB; it reflects immunological control of the infection and confers an excellent prognosis in the absence of pre-existing cirrhosis or concurrent infections[9-11]. It is becoming apparent that information on HBsAg levels can add to our understanding of both the natural history of the disease and its response to therapy. The relationship between HBsAg and serum HBV DNA is complex. HBsAg titer is correlated with serum HBV DNA only in patients with HBeAg-positive CHB, and not in patients with HBeAg-negative CHB[12]. The same pattern was shown in the present study: that HBsAg titer had a significant positive correlation with HBV DNA level in all 55 HBeAg-positive patients at baseline recruitment. Similarly, HBsAg and HBV DNA showed a significant correlation in 150 HBeAg-positive patients in a recent Korean retrospective cross-sectional study[13]. Additionally, baseline HBsAg quantification provides different but complementary information for prediction of treatment response. In the present study, the group with HBsAg levels > 20000 IU/mL and < 20000 IU/mL at baseline recruitment showed a significant difference in terms of virological response rate (P = 0.02) after 48 wk of PEG-IFN-α2b therapy, indicating that baseline HBsAg levels had a valuable predictive effect on HBV DNA negative conversion. Not only in HBeAg-positive patients recruited in this study, but also in a recent study of 48 HBeAg-negative patients, low baseline HBsAg levels strongly predicted the probability of HBsAg disappearance after two years of follow-up[14]. Takkenberg et al[14] reported that in HBeAg-negative patients receiving adefovir dipivoxil and PEG-IFN-α2a treatment for 48 wk with follow-up for two years, low baseline HBsAg levels can predict HBV DNA negative conversion and HBsAg disappearance, which is deduced to relate to low viral loading capacity. Our data showed that HBsAg was positively correlated with HBV DNA quantity in HBeAg-positive hepatitis B patients, indicating that HBsAg reflects the HBV DNA replication status to some extent. It is becoming apparent that information on HBsAg levels can add to our understanding of both the natural history of the disease and its response to therapy. The reduction in serum HBV DNA reflects a decrease in virus replication, and a decline in serum HBsAg represents a reduction of transcriptional covalently closed circular DNA activity or the messenger of integrated sequence of RNA translation[15]. Therefore, the HBsAg quantitative value provides different but complementary information and aids in determining the individual infection characteristics, thus providing the theoretical basis for patients with high baseline HBsAg and HBV DNA level in choosing initial combination therapy or extending the existing treatment course. After receiving IFN therapy for 48 wk, most patients in this group discontinued the treatment, and some of them were transferred to antiviral therapy with nucleoside analogs.

Furthermore, besides the therapeutic value of baseline HBsAg levels, close monitoring of quantitative HBsAg values during treatment also helps the prediction of treatment response. This study is believed to be the first retrospective study of HBsAg changes during PEG-IFN treatment in HBeAg-positive CHB patients. We set up 0.5 log10 decrease at week 12 (43 patients) and 1.0 log10 decrease at week 24 (48 patients) as monitoring points. Even though the HBV DNA negative conversion rate was greater in both > 0.5 log10/1.0 log10 groups compared to < 0.5 log10/1.0 log10 groups (46.15% vs 33.33% and 44.44% vs 36.67%, respectively), there was no significant difference between these groups in our study. This finding may be due to the number of patients recruited and the common bias of a retrospective study. Similar studies focused on dynamic variation in HBsAg values during treatment had similar findings. Studies have only been carried out in nucleos(t)ide analog (NA) treatment, and the present study is believed to be the first retrospective study on HBsAg changes during PEG-IFN treatment of HBeAg-positive CHB patients. Given different NA treatments, all three studies have suggested that patients who have HBsAg loss tend to have higher baseline HBsAg levels and a more rapid decline in HBsAg level as compared to those who failed to lose HBsAg with long-term NA treatment[16-18]. These studies also implied that genotype A and D CHB patients have higher baseline HBsAg and more continuous decline in HBsAg than genotype B and C CHB patients[17,18]. In a small study in China, among 11 HBeAg-positive patients who were treated with telbivudine for 2 years, HBsAg < 100 IU/mL at the end of treatment predicted a sustained response (defined as undetectable HBV DNA, normal ALT and HBeAg seroconversion) for two years after stopping treatment[18]. Among HBeAg-negative patients with CHB, it has also been shown that patients with serum HBsAg that declined by 0.5 log10 and 1.0 log10 IU/mL, respectively, after 12 and 24 wk of treatment had a higher rate of sustained response prediction[19-21]. Therefore, in clinical practice, in both HBeAg-positive and -negative patients, serum HBsAg levels should be used together with, but not as a substitute for, HBV DNA measurement[22,23].

Patients who had 48 wk of PEG-IFN-α2b therapy and had HBsAg levels > 20000 IU/mL at 24 wk did not show HBV DNA negative conversion. Sonneveld et al[24] have claimed that HBsAg is a strong predictive index for IFN therapy in HBsAg-positive CHB patients. For all patients with HBsAg levels > 20000 IU/mL by 24 wk of PEG-IFN therapy, withdrawal of treatment should be considered. Similar findings have been shown in several studies[25,26]. Therefore, in clinical practice, we can observe the change in HBsAg levels dynamically in combination with indicators such as HBeAg, HBV DNA and ALT, and take the time point of 24 wk of therapy to predict the long-term efficacy. It will be important to identify a level of serum HBsAg reduction or a cut-off that is associated with subsequent HBsAg loss. For patients with poor predictive efficacy at 24 wk of therapy, either combination with NAs or discontinuation of treatment should be considered.

In Asia, 5%-10% of adults and up to 90% of infants among 50 million new cases of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection will become chronically infected annually, which is the leading cause of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Ideally, these chronic carriers should be identified and medical interventions implemented to reduce the risk of premature death. The International Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommends Pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN)-α as standard therapy and regularly updates its guidance related to the sustained response rate to IFN.

Recent studies indicate that hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) quantification might be a useful complement to HBV DNA quantification for clinical assessment and treatment monitoring in patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB). The quantitative measurement of HBsAg in combination with HBV DNA detection may aid clinicians in creating a specific therapeutic regimen for individual patients.

Studies have been carried out among CHB patients who were hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-negative and under nucleoside (nucleotide) analog (NA) treatment. The findings all indicated that the quantitative measurement of HBsAg at baseline and during treatment was a good indicator of HBsAg seroconversion, which is of significance to cure CHB.

In the present study, the authors showed that: (1) baseline HBsAg values were a good indicator of HBsAg seroconversion; and (2) Dynamic HBsAg measurement along with the Peg-IFN-α2b treatment are important in the treatment of CHB patients.

For patients with poor predictive efficacy at 24 wk therapy, either combination therapy with NA or discontinuation of treatment should be considered. For all CHB patients undergoing treatment, it is clinically relevant and important to keep a record of immunological and virological data at baseline and at each time point during treatment or off-treatment for future clinical assessment.

HBsAg is the surface antigen of HBV. It indicates CHB infection. The viral envelope of the virus has different surface proteins from the rest of the virus that act as antigens. These antigens are recognized by antibodies that bind specifically to one of these surface proteins.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first retrospective study among HBeAg-positive patients with CHB under PEG-IFN-α2b treatment to collect and analyze HBsAg at baseline and during treatment. The results are consistent with previous findings among CHB patients under NA treatment, which emphasize the importance of understanding the pathogenesis of CHB.

P- Reviewers: Allam N, Jutavijittum P S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Logan S E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Mohamed R, Ng CJ, Tong WT, Abidin SZ, Wong LP, Low WY. Knowledge, attitudes and practices among people with chronic hepatitis B attending a hepatology clinic in Malaysia: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Liaw YF. Impact of therapy on the long-term outcome of chronic hepatitis B. Clin Liver Dis. 2013;17:413-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tujios SR, Lee WM. Update in the management of chronic hepatitis B. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2013;29:250-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Larsson SB, Eilard A, Malmström S, Hannoun C, Dhillon AP, Norkrans G, Lindh M. HBsAg quantification for identification of liver disease in chronic hepatitis B virus carriers. Liver Int. 2013;Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sonneveld MJ, Zoutendijk R, Janssen HL. Hepatitis B surface antigen monitoring and management of chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:449-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liaw YF. Clinical utility of hepatitis B surface antigen quantitation in patients with chronic hepatitis B: a review. Hepatology. 2011;54:E1-E9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chinese Society of Hepatology. Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association. The guideline of prevention and treatment for chronic hepatitis B (2010 version). Zhongguo Linchuang Ganranxing Jibing. 2011;4:1-13. |

| 8. | Blumberg BS, Alter HJ, Visnich S. A “new” antigen in leukemia sera. JAMA. 1965;191:541-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 933] [Cited by in RCA: 733] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2125] [Cited by in RCA: 2171] [Article Influence: 135.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liaw YF, Leung N, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T, Gane E, Han KH, Guan R, Lau GK, Locarnini S. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2008 update. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:263-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 666] [Cited by in RCA: 743] [Article Influence: 43.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jang JW, Yoo SH, Kwon JH, You CR, Lee S, Lee JH, Chung KW. Serum hepatitis B surface antigen levels in the natural history of chronic hepatitis B infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1337-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Thompson AJ, Nguyen T, Iser D, Ayres A, Jackson K, Littlejohn M, Slavin J, Bowden S, Gane EJ, Abbott W. Serum hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis B e antigen titers: disease phase influences correlation with viral load and intrahepatic hepatitis B virus markers. Hepatology. 2010;51:1933-1944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 329] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim YJ, Cho HC, Choi MS, Lee JH, Koh KC, Yoo BC, Paik SW. The change of the quantitative HBsAg level during the natural course of chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int. 2011;31:817-823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Takkenberg RB, Jansen L, de Niet A, Zaaijer HL, Weegink CJ, Terpstra V, Dijkgraaf MG, Molenkamp R, Jansen PL, Koot M. Baseline hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) as predictor of sustained HBsAg loss in chronic hepatitis B patients treated with pegylated interferon-α2a and adefovir. Antivir Ther. 2013;18:895-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hadziyannis E, Hadziyannis SJ. Hepatitis B surface antigen quantification in chronic hepatitis B and its clinical utility. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;8:185-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wursthorn K, Jung M, Riva A, Goodman ZD, Lopez P, Bao W, Manns MP, Wedemeyer H, Naoumov NV. Kinetics of hepatitis B surface antigen decline during 3 years of telbivudine treatment in hepatitis B e antigen-positive patients. Hepatology. 2010;52:1611-1620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Heathcote EJ, Marcellin P, Buti M, Gane E, De Man RA, Krastev Z, Germanidis G, Lee SS, Flisiak R, Kaita K. Three-year efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate treatment for chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:132-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in RCA: 364] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cai W, Xie Q, An B, Wang H, Zhou X, Zhao G, Guo Q, Gu R, Bao S. On-treatment serum HBsAg level is predictive of sustained off-treatment virologic response to telbivudine in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients. J Clin Virol. 2010;48:22-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Papatheodoridis G, Goulis J, Manolakopoulos S, Margariti A, Exarchos X, Kokkonis G, Hadziyiannis E, Papaioannou C, Manesis E, Pectasides D. Changes of HBsAg and interferon-inducible protein 10 serum levels in naive HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B patients under 4-year entecavir therapy. J Hepatol. 2014;60:62-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Moucari R, Mackiewicz V, Lada O, Ripault MP, Castelnau C, Martinot-Peignoux M, Dauvergne A, Asselah T, Boyer N, Bedossa P. Early serum HBsAg drop: a strong predictor of sustained virological response to pegylated interferon alfa-2a in HBeAg-negative patients. Hepatology. 2009;49:1151-1157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 361] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Brunetto MR, Moriconi F, Bonino F, Lau GK, Farci P, Yurdaydin C, Piratvisuth T, Luo K, Wang Y, Hadziyannis S. Hepatitis B virus surface antigen levels: a guide to sustained response to peginterferon alfa-2a in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2009;49:1141-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 358] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sonneveld MJ, Zoutendijk R, Flink HJ, Zwang L, Hansen BE, Janssen HL. Close monitoring of hepatitis B surface antigen levels helps classify flares during peginterferon therapy and predicts treatment response. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:100-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chan HL, Thompson A, Martinot-Peignoux M, Piratvisuth T, Cornberg M, Brunetto MR, Tillmann HL, Kao JH, Jia JD, Wedemeyer H. Hepatitis B surface antigen quantification: why and how to use it in 2011 - a core group report. J Hepatol. 2011;55:1121-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sonneveld MJ, Hansen BE, Piratvisuth T, Jia JD, Zeuzem S, Gane E, Liaw YF, Xie Q, Heathcote EJ, Chan HL. Response-guided peginterferon therapy in hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B using serum hepatitis B surface antigen levels. Hepatology. 2013;58:872-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Yu HB, Liu EQ, Lu SM, Zhao SH. Treatment with peginterferon versus interferon in Chinese patients with hepatitis B. Biomed Pharmacother. 2010;64:559-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Huang Z, Deng H, Zhao Q, Zheng Y, Peng L, Lin C, Zhao Z, Gao Z. Peginterferon-α2a combined with response-guided short-term lamivudine improves response rate in hepatitis B e antigen-positive hepatitis B patients: a pilot study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:1165-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |