Published online Jun 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7988

Revised: April 15, 2014

Accepted: April 28, 2014

Published online: June 28, 2014

Processing time: 106 Days and 10.3 Hours

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is an uncommon, rapidly progressive, and potentially fatal infection of the superficial fascia and subcutaneous tissue. NF caused by an enterocutaneous fistula has special clinical characters compared with other types of NF. NF caused by enterocutaneous fistula may have more rapid progress and more severe consequences because of multiple germs infection and corrosion by digestive juices. We treated three cases of NF caused by postoperative enterocutaneous fistula since Jan 2007. We followed empirically the principle of eliminating anaerobic conditions of infection, bypassing or draining digestive juice from the fistula and changing dressings with moist exposed burn therapy impregnated with zinc/silver acetate. These three cases were eventually cured by debridement, antibiotics and wound management.

Core tip: Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) caused by enterocutaneous fistula may have more rapid progress and more severe consequences because of multiple bacterial infection and corrosion by digestive juices. Treating with three cases of NF secondary to enterocutaneous fistula, indicated that it was vital to heal NF by eliminating anaerobic conditions of infection, bypassing or draining digestive juice from fistula, and changing dressings with moist burn medical technology.

- Citation: Gu GL, Wang L, Wei XM, Li M, Zhang J. Necrotizing fasciitis secondary to enterocutaneous fistula: Three case reports. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(24): 7988-7992

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i24/7988.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7988

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is an uncommon, rapidly progressive, and potentially fatal infection of the superficial fascia and subcutaneous tissue[1]. NF caused by an enterocutaneous fistula has special clinical characters compared with other types of NF[2]. We treated successfully three cases of NF caused by postoperative enterocutaneous fistula since January 2007. From these three cases, we learned it was vital to heal NF by eliminating anaerobic conditions of infection, bypassing or draining digestive juice from fistula and changing dressings with moist exposed burn therapy.

A 72-year-old male patient was hospitalized with severe infection of the abdominal wall. He had undergone distal gastrectomy and duodenal drainage for a gastric ulcer with pyloric obstruction in another hospital 46 d previously. The first sign of NF was that bile and intestinal juice continuously flowed out around the drainage tube since postoperative day 4. He then presented continued high fever (39 °C or more), and inflamed soft-tissue area of the abdominal wall ranged from the right costal margin to the symphysis pubis. After treatment with antibiotics, drainage and dressing changes for about 1 mo, his temperature returned to normal. However, a great deal of pus continuously oozed from the short incisions of the inflamed area. He had a history of chronic bronchitis for about 10 years.

On physical examination, the inflamed area of the right abdominal wall was about 22 cm × 14 cm in size, and yellow-green pus with a bad smell pooled under skin. A CT scan confirmed a duodenal fistula with digestive juice leakage. His white blood cell (WBC) count was 15.2 × 109/L.

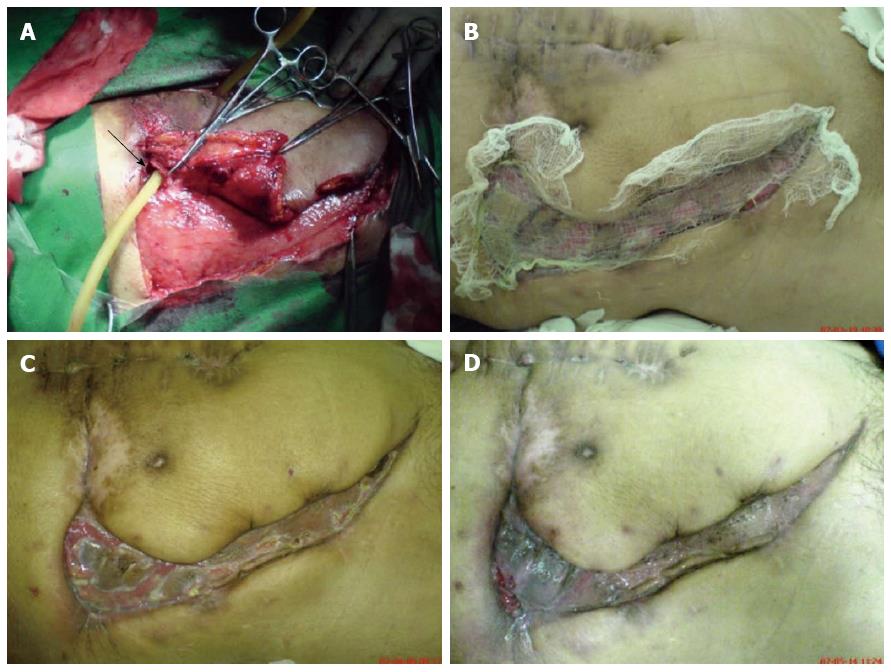

He was immediately treated by abdominal debridement and fistula drainage as soon as the diagnosis of NF was made (Figure 1A). Liquefactive necrosis was found with wide extension in the subcutaneous fascia tissue of the abdominal wall during surgical exploration. Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) were detected from pus culture with high sensitivity to Imipenem, Amikacin and Ceftazidime. After debridement of the necrotic tissue, fistula drainage, wet compress with Amikacin and moist exposed burn ointment for about 1 mo, the fistula gradually healed with cicatrization, and the purulent masses decreased. He then underwent self-skin split graft (Figure 1B). The skin grafts survived and ultimately inosculated (Figure 1C). The wound then gradually healed (Figure 1D).

A 46-year-old male patient complained of swelling and pain in his right buttock and hip for about five months, with obvious aggravation and a high fever for 1 wk. He had a history of total colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis for familial adenomatous polyposis 8 years ago.

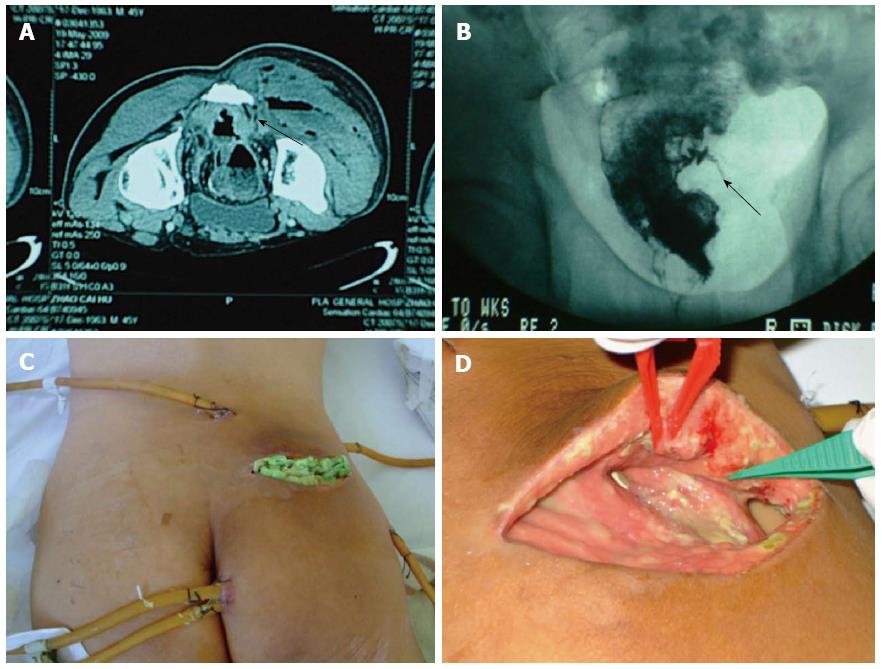

Physical examination revealed a swollen area with fluctuation and crepitus in the right buttock was about 20cm in diameter. His temperature was 39.2 °C, and his WBC count was 32.2 × 109/L. CT scans showed that the soft tissue of the right buttock was filled with hydrops and pneumatosis (Figure 2A). Barium enema examination revealed a fistula connected to anastomosis within the soft tissue of right buttock (Figure 2B).

After being diagnosed as NF with abscess, he successively underwent radical debridement, drainage (Figure 2C) and ileostomy. Subcutaneous fascia tissue of his right buttock showed significant liquefactive necrosis, necrotic tissue and about 1000 mL yellow pus with stench were debrided (Figure 2D). Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) and P. aeruginosa were detected from the pus culture with high sensitivity to gentamycin. After lavage with 3% oxydol, the wound was packed with gentamycin saline gauze and moist exposed burn ointment for about 1 mo. The purulent exudates disappeared and the drainage tubes were removed. The wound gradually healed well.

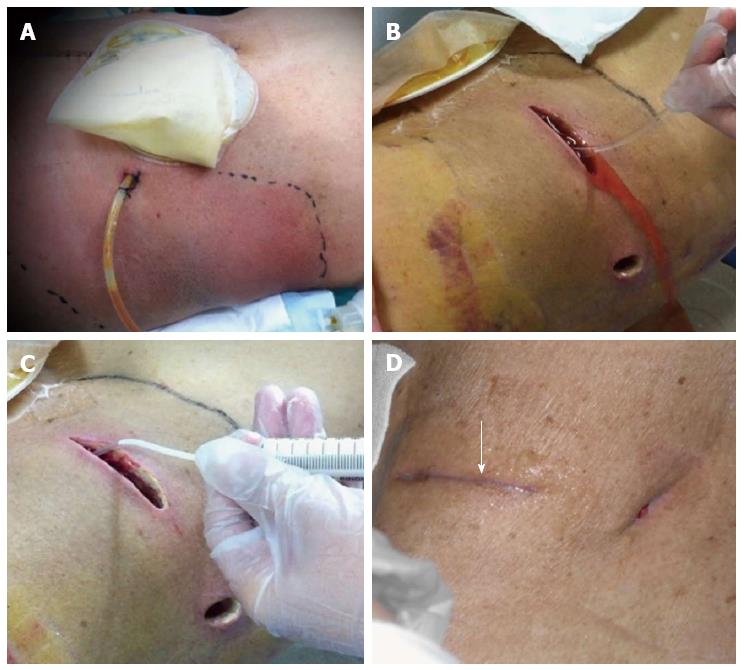

A 67-year-old male patient underwent abdominoperineal resection for rectal cancer. He presented with a fever of 38.9 °C since postoperative 6th day, and a painful, swollen parastomal abdominal wall that ranged from the left costal margin to the symphysis pubis. Physical examination revealed an inflamed area of parastomal abdominal wall that was about 12 cm × 15 cm in size (Figure 3A). His WBC count was 19.0 × 109/L. A CT scan confirmed that a parastomal fistula had formed and the soft tissues of the parastomal abdominal wall were inhomogeneous in density.

After being diagnosed as NF of the abdominal wall caused by a parastomal fistula, he immediately was treated with debridement and drainage of the fistula (Figure 3B). Liquefactive necrosis was found widely in the subcutaneous fascia tissue of the parastomal abdominal wall during surgical exploration. Necrotic tissue and about 300 mL bloody, stinking pus were debrided. E. coli and Enterobacter cloacae were detected from the pus culture with high sensitivity to Imipenem, Amikacin and Ceftazidime. After washing the wound with 0.9% saline solution, we employed wet compresses with silver ion dressings and applied moist exposed burn ointment for 45 d (Figure 3C); the wound finally healed well (Figure 3D).

NF caused by an enterocutaneous fistula has special clinical characters compared with other types of NF. Intestinal contents containing a large amount of bacteria and various digestive enzymes are brought into truncal subcutaneous fascia tissue along the fistula[3]. Thus the inflammation and necrosis of truncal fascia tissue not only occurs from multiple bacterial infections, but also from corrosion by digestive juices and enzymes. For this reason, the inflammation of NF caused by an enterocutaneous fistula may have more rapid progress and greater severity.

Aggressive surgical debridement with antibiotic therapy would profoundly affect outcome of NF. For NF caused by an enterocutaneous fistula, the purpose of debridement is not only the removal of necrotic tissue, but also clearing away the anaerobic environment in which anaerobic bacteria survive. Even facultative anaerobic bacteria, which are commonly found in NF, are suppressed in an aerobic environment[4]. Drainage or bypass of the fistula is vital to cure NF caused by an enterocutaneous fistula, otherwise the intestinal contents along fistula would continuously contaminate the wound and prevent wound healing.

Skin grafting is an efficient method to accelerate wound healing[5]. However, the grafted skin finds it very difficult to survive in the wound of NF. We suggest that skin grafting should only be performed when the granulated tissue grows better and the wound is clean without purulent secretion. Moist exposed burn therapy and moist exposed burn ointment are better than traditional dressings[6], because keeping the wound moist can prevent shrinkage of the incision. The main components of moist exposed burn ointment are zinc acetate and silver acetate. Silver and zinc ions have strong bacteriostatic functions toward E. faecalis, P. aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella. Moreover, as an activating agent of biological enzymes, zinc ions can accelerate the synthesis of protein and nucleic acid to promote wound healing[7].

We obtained consent for publication in print and electronically from the patients of these cases reports when they were hospitalized again for postoperative check-up.

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) perhaps is the most severe form of soft tissue infection primarily involving the superficial fascia.

Early findings in NF are tenderness to palpation (extending beyond the apparent area of skin involvement), swelling, erythema, and warmth to palpation. The intermediate findings are marked by serous-filled blisters or bullae formation along with skin fluctuation and induration. The late findings are hemorrhagic bullae, skin anesthesia, crepitus, and skin necrosis with dusky discoloration progressing to gangrene.

It is critical to promptly differentiate a case of NF from cellulitis or abscesses in the clinic.

Three most commonly cultured organisms in NF were Staphylococcus aureus, group A Streptococcus, and Escherichia coli.

Findings of NF found on computed tomography (CT) are fat stranding, along with fluid and gas collections that dissect along fascial planes. Additionally, fascial thickening and non-enhancing fascia on contrast CT suggest fascial necrosis.

The skin findings of NF are induration and advancing erythema, followed by the development of overlying blisters and skin necrosis.

NF is a clinical diagnosis where only emergent surgical debridement and appropriate antibiotic treatment can prevent progression and death.

NF is an uncommon, rapidly progressive, and potentially fatal infection of the superficial fascia and subcutaneous tissue.

It was vital for healing NF to eliminate anaerobic conditions of infection, bypass or drain digestive juice from fistula and change the dressing with moist exposed burn therapy.

The three cases reports were generally clearly presented in the manuscript. The manuscript is very well written. NF is an uncommon, rapidly progressive, and potentially fatal infection of the superficial fascia and subcutaneous tissue. NF caused by an enterocutaneous fistula has special clinical characters compared with other types of NF. The authors treated successfully three cases of NF caused by postoperative enterocutaneous fistula, and found it was vital for healing NF to eliminate anaerobic conditions of infection, bypass or drain digestive juice from fistula and change the dressing with moist exposed burn therapy.

P- Reviewers: Coughlin S, Orbell JH S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Stewart G E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Liu SY, Ng SS, Lee JF. Multi-limb necrotizing fasciitis in a patient with rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5256-5258. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Takeda M, Higashi Y, Shoji T, Hiraide T, Maruo H. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by a primary appendicocutaneous fistula. Surg Today. 2012;42:781-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Carter JS, Hutto SL, Asghar JI, Teoh DG. Necrotizing fasciitis after placement of intraperitoneal catheter. Gynecol Oncol Case Rep. 2013;5:55-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Adachi M, Tsuruta D, Imanishi H, Ishii M, Kobayashi H. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Cryptococcus neoformans in a patient with pemphigus vegetans. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e751-e753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bagri N, Saha A, Dubey NK, Rai A, Bhattacharya S. Skin grafting for necrotizing fasciitis in a child with nephrotic syndrome. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2013;7:496-498. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Saraf S. Moist exposed burn ointment: role of alternative therapy in the management of partial-thickness burns. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:415-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Arhi C, El-Gaddal A. Use of a silver dressing for management of an open abdominal wound complicated by an enterocutaneous fistula-from hospital to community. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2013;40:101-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |