Published online May 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i19.5912

Revised: December 2, 2013

Accepted: January 3, 2014

Published online: May 21, 2014

Processing time: 198 Days and 6.6 Hours

Adalimumab (ADA) is a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor, used for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Previous studies have reported an increased risk of cancer following exposure to TNF inhibitors, but little has been reported for patients with cancer receiving TNF-inhibitor treatment. We present a female patient with metastatic breast cancer and ulcerative colitis (UC) who was treated with ADA. A 54-year-old African American female with a past history of left-sided breast cancer (BC) diagnosed at age 30 was initially treated with left-breast lumpectomy, axillary dissection, followed by chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Years after initial diagnosis, she developed recurrent, bilateral BC and had bilateral mastectomy. Subsequent restaging computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated distant metastases to the bone and lymph nodes. Three years into her treatment of metastatic breast cancer, she was diagnosed with UC by colonoscopy. Her UC was not controlled for 5 mo with 5-aminosalicylates. Subcutaneous ADA was started and resulted in dramatic improvement of UC. Four months after starting ADA, along with ongoing chemotherapy, restaging CT scan showed resolution of the previously seen metastatic lymph nodes. Bone scan and follow-up positron emission tomography/CT scans performed every 6 mo indicated the stability of healed metastatic bone lesions for the past 3 years on ADA. While TNF-α inhibitors could theoretically promote further metastases in patients with prior cancer, this is the first report of a patient with metastatic breast cancer in whom the cancer has remained stable for 3 years after ADA initiation for UC.

Core tip: Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitors are widely-used and effective treatments for many autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease and psoriasis. However, it is believed that TNF-α inhibitors may also place patients at increased risk of cancer occurrence or recurrence. Many studies report increased risk of cancer following exposure to TNF-α inhibitors, but little has been reported for patients with cancer, receiving anti-TNF-α treatment. This is the first case of metastatic breast cancer in long term remission for 3 years in a patient treated with TNF-α inhibitors for ulcerative colitis, suggesting that patients with metastatic cancer could be treated with this class of medications without worsening.

- Citation: Ben Musa R, Usha L, Hibbeln J, Mutlu EA. TNF inhibitors to treat ulcerative colitis in a metastatic breast cancer patient: A case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(19): 5912-5917

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i19/5912.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i19.5912

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) is a proinflammatory cytokine that plays a major role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)[1]. IBD patients are often administered prolonged treatment with anti-TNF-α agents. Adalimumab (ADA) is a monoclonal antibody that blocks the interaction of TNF-α with its cell surface receptors[2]. In the past, several small open-label trials and case reports had suggested that ADA is an effective therapy for ulcerative colitis (UC)[1,3-5]. Recently, a randomized controlled trial demonstrated that ADA is effective in inducing and maintaining clinical remission in patients with moderate to severe UC, who did not have an adequate response to conventional therapy with steroids[2].

TNF-α acts as an early tumor suppressor, thus drugs blocking TNF-α may possibly increase the risk of initial occurrence of malignancies, especially in those patients with long-term therapy[6-8]. Additionally, blocking TNF-α can also possibly lead to reactivation of latent malignancies[7]. Little has been reported on patients with cancer receiving anti-TNF-α treatment, and the issues concerning the long-term safety of these biologic agents in patients with prior malignancy remain to be clarified. We report the first case of metastatic breast cancer treated with ADA for UC.

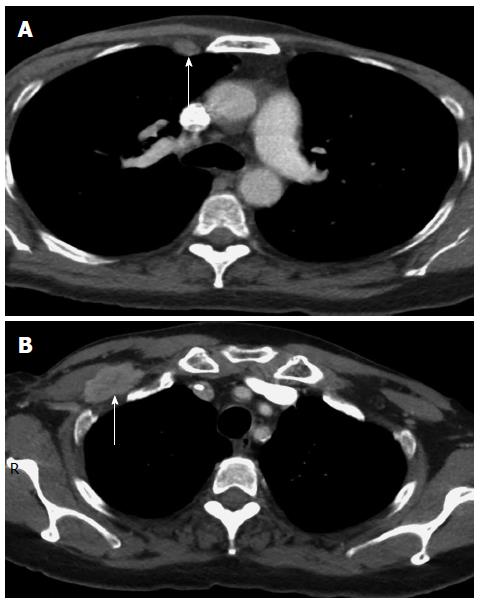

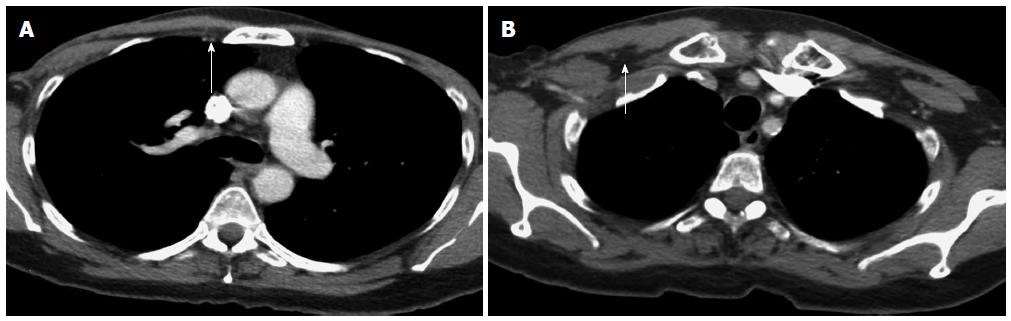

A 54-year-old African American female was initially diagnosed in 1989 with left sided breast cancer (BC) at the age of 30. She was treated with a left-breast lumpectomy and axillary dissection, followed by four cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy with CMF (cytoxan, methotrexate, 5-fluorouracil). The chemotherapy was discontinued due to side effects. She then received radiotherapy to the left breast, and had no further treatment following that. In 2007, she developed recurrent, bilateral BC. Bilateral mastectomy with right axillary lymph node dissection in 2007 showed metastases in 14 out of 16 right axillary lymph nodes. The tumor was estrogen receptor (ER) negative, progesterone receptor (PR) negative, Her-2/neu (human epidermal growth factor receptor) positive by immunohistochemistry (IHC) with amplified fluorescence in situ hybridization. In addition to the axillary nodes that were histologically positive, restaging computed tomography (CT) scan after the surgery showed metastatic disease also in the internal mammary lymph nodes (Figure 1A) and thoracic spine. Biopsies for histologic confirmation of the additional metastatic lesions were not attempted due to high-risk for cancer progression, poor accessibility of the metastases, and compelling imaging. She was started on chemotherapy with vinorelbine and trastuzumab as well as zoledronic acid. Vinorelbine was discontinued after one cycle due to severe myalgias. The patient continued to receive trastuzumab, and zoledronic acid for 11 mo; then, paclitaxel was added at low dose due to the development of right retropectoral lymphadenopathy (Figure 1B). She had stable disease on this regimen for 15 mo, until she developed right supraclavicular lymphadenopathy and further progression of the right retropectoral lymphadenopathy. Also, her tumor marker, carcinogenic embryonic antigen (CEA), rose dramatically at that time and reached a level of 70 ng/mL. This necessitated changing her chemotherapy regimen to gemcitabine and trastuzumab, while continuing zoledronic acid. After 2 mo with this new regimen, she was diagnosed with severe pancolitis, compatible with UC on colonoscopy and biopsies, following an acute episode of diffuse abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea. Gemcitabine was discontinued, but she was continued on trastuzumab and zoledronic acid for an additional 6 mo after the UC diagnosis, when she was found to have cancer progression in the right supraclavicular lymph nodes, and when she was diagnosed with right mandibular osteonecrosis due to zoledronic acid. At that time, zoledronic acid and trastuzumab were discontinued, and the patient was started on capecitabine and lapatinib. She had stable disease on this regimen and she was continued on this regimen for 22 mo and then was continued on lapatinib as a single agent. For UC, she was started on 5- aminosalicylates and prednisone, but her UC was not controlled for 5 mo on this regimen, as the tumor was progressing. Subcutaneous ADA (40 mg every 2 wk) was started and resulted in dramatic improvement of her UC symptoms. Four months after starting ADA along with ongoing chemotherapy with capecitabine and lapatinib, restaging CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis showed the resolution of the previously seen internal mammary lymph nodes (Figure 2A), and the right retropectoral lymph node (Figure 2B) and no evidence of distant metastases. Bone scan and follow-up PET/CT scans performed every 6 mo indicated metabolically inactive lesions at the prior sites of metastatic bone lesions suggesting control of BC for the past 3 years on ADA. She has been clinically asymptomatic and progression free since 2010. Currently, she remains in complete clinical remission on maintenance lapatinib. In 2013, she had a biopsy of her L4 vertebral body to look for histological metastatic disease to the bone; and the pathology was benign. She was genetically tested for BC predisposition and found to have no BRCA1 and 2 mutations by full sequencing of both genes.

Many studies have been undertaken to understand whether TNF-α inhibitor therapy increases the rate of malignancies. The hypothetical risk of recurrent malignancy in patients with prior malignancy has previously led researchers to exclude almost all cancer patients from randomized clinical trials of TNF-α inhibitors[9]. TNF-α inhibitor therapy, in general, and ADA in particular, has been associated with an increased risk for malignancy[10]. A meta-analysis of nine randomized controlled trials of anti-TNF-α antibody therapies (infliximab and ADA) versus placebo in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, found a significantly increased risk for malignancies in the TNF-α inhibitor treated patients with a pooled odds ratio of 3.3 (95%CI: 1.2-9.1), compared to placebo-treated patients[11]. Another meta-analysis[12] found a higher malignancy risk in patients treated with etanercept compared to controls, although the relative risk estimate did not achieve statistical significance.

While malignancy risk in general seems increased in patients receiving TNF inhibitors, when the type of malignancies are examined, most common ones encountered are lymphomas and skin cancers. In particular, among IBD patients, a meta-analysis by Siegel et al[13] found a significant increase in NHLs. In 26 studies that enrolled a total of 8905 patients with 21178 patient-years of follow-up, 13 cases of NHL were reported (6.1/10000 patient-years) among TNF-α inhibitor treated subjects. This rise in NHLs was also confirmed in another meta-analysis by Wong et al[14]. In the literature, there are also several case reports that highlight an increased risk of lymphoma development after initiation of TNF-α inhibitors[15-18]. Among other malignancies in case reports of patients exposed to TNF-α inhibitors are a papillary thyroid carcinoma[19]; a salivary gland tumor[20]; a metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast and a diffuse B-cell lymphoma (after high-dose of ADA)[21]; malignant melanomas[22,23]; and a pulmonary carcinoid tumor[24].

While a potential role of TNF-α inhibitors in the development of lymphoma and skin cancers is fairly well accepted, the role of TNF-α inhibitors in solid malignancies is not as clear. A possible theory regarding the risk of cancer in patients on TNF-α inhibitors relates to the important role of TNF-α for natural killer/CD8 lymphocyte dependent cell lysis and for modulating adaptive immunity, which is an important component of tumor surveillance[25,26]. Therefore, it is postulated that suppressing TNF-α may enhance proliferation of solid organ malignancies[25,26]. However, in an observational study, Wolfe et al[27] analyzed the association between malignancy and biologic therapy in approximately 13000 patients with RA, and reported that there were no increases in the risk of solid tumors. Another observational study by Askling et al[28,29] used the Swedish inpatient registry to compare 4160 TNF-α inhibitor treated patients with 53067 other patients in the registry: Cancer risks in the TNF inhibitor treated patients were largely similar to those of other patients with RA.

Data regarding the safety of anti-TNF-α agents prescribed to patients with prior malignancy are available in only a few studies. One study analyzed data from the British Society of Rheumatology Biologics Register and attempted to assess the potential malignancy risk associated with starting TNF-α inhibitor therapy in patients with RA who had pre-existing malignancies[30]: Analysis of data from approximately 10000 patients, showed an increased incidence rate ratio of 2.5 (95%CI: 1.2-5.8); indicating that patients with a malignancy prior to the initiation of TNF-α inhibitor therapy have a higher risk of another malignancy compared to patients without a previous malignancy. In contrast, a recent study found no significant increase in the risk of tumor recurrence for those patients under treatment with TNF-α inhibitor agents, and no overall increase in the incidence of malignancies in patients exposed or unexposed to TNF-α inhibitor treatment[6]. Additionally, clinical trials of the TNF-α inhibitor etanercept in patients with breast cancer, ovarian cancer and hematological malignancies have resulted in disease stabilization or partial improvement of the cancer[31-33]. Also, infliximab therapy of 41 patients with advanced cancer was well tolerated with no evidence of disease acceleration[34]. But tumor recurrence was reported in two cases of metastatic melanoma and these occurred after initiation of TNF-α inhibitors[35].

In the terms of tumor regression with withdrawal of TNF inhibitors, there are two case reports: One is a case of recurrent Hodgkin’s lymphoma, 10 mo after ADA initiation, with spontaneous regression observed after withdrawal of TNF-α inhibition[36]. The other is a case report of a non-small cell lung cancer developing 4 years after TNF-α inhibitors in a patient with Crohn’s disease treated initially with infliximab for 2 years and then with ADA. The tumor was found to have TNF receptors type 1 and type 2. After TNF-α inhibitors were withdrawn, the tumor regressed with follow-up chest CT scans 1 year after withdrawal, showing virtually no evidence of the primary lung tumor, nodules, or lymphadenopathy, with complete clinical and radiological remission[37]. Looking at these reports, it is clear that in some patients TNF-α inhibitors may further cancer and in others they do not. Additional studies on tumor characteristics and immune mechanisms at play are needed to determine in which patients TNF-α inhibitors may be harmful.

The case reported here is remarkable because our patient with metastatic BC achieved a complete remission despite initiation of TNF-α inhibitors (which theoretically can worsen malignancies) and she has been progression free for 3 years, along with excellent control of her UC. This case is also interesting because UC could have accounted for the rising CEA observed. Some previous studies suggest that the elevation of CEA titers in some patients can be related to the degree and the extent of active inflammation of the colon and can return to normal with remission[38,39]. In this case, the CEA was difficult to interpret due to the presence of both metastatic BC and active colitis.

In terms of TNF-α therapy, the potential benefits of the latter therapy need to be considered against risks related to the potential recurrence of pre-existing malignancy. If patients have been free of any recurrence of their malignancy for 10 years, there appears to be no evidence for a contraindication to anti-TNF-α therapy[40]. On the basis of all available data, the question of whether anti-TNF-α therapy can be initiated in individuals with previous malignancies less than 10 years in remission is still not solved and requires careful data collection going forward[41]. Our case, illustrates that, it is possible to successfully treat an advanced cancer like metastatic BC and concomitant IBD with TNF-α inhibitor therapy. Further in-depth studies are needed in cancer patients who remain in remission, who are also given TNF-α inhibition to elucidate the role of TNF-α in tumor progression and surveillance.

A 54-year-old female with past history of breast cancer presented with tumor recurrence and developed bloody diarrhea three years into the course of treatment for metastatic breast cancer.

The patient was diagnosed with colitis, while getting treated for metastatic breast cancer.

The differential diagnosis included infectious diarrhea vs other causes of colitis.

The patient was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis on the basis of colonoscopy and biopsies; and also had a rising carcinogenic embryonic antigen.

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest before treatment of ulcerative colitis showed enlarged internal mammary lymph nodes and a large retropectoral lymph node; but a follow-up CT scan 4 mo after initiation adalimumab therapy showed resolution of the previously demonstrated metastatic lymphadenopathy.

Bilateral mastectomy with right axillary lymph node dissection showed metastases in 14 out of 16 right axillary lymph nodes. The tumor was estrogen receptor negative, progesterone receptor negative, Her-2/neu (human epidermal growth factor receptor) positive by immunohistochemistry with amplified fluorescence in situ hybridization.

After the development of ulcerative colitis, the patient was treated with capecitabine and lapatinib for metastatic breast cancer, and 5-ASAs and steroids for ulcerative colitis; and after 5 mo, the ulcerative colitis treatment had to be changed to adalimumab, following which rapid resolution of the patient’s colitis symptoms and regression of the metastatic lesions occurred.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitors such as adalimumab have been reported to increase the risk of occurrence of malignancies but little has been reported for patients with cancer, receiving anti-TNF-α treatment.

IHC is used to characterize various surface and intracellular proteins from cells of all types of tissues ratio between the numbers of HER2 and CEP17 sequences.

Ulcerative colitis was successfully treated in a patient with metastatic breast cancer, using adalimumab, suggesting that metastatic cancer with solid tumors is not an absolute contraindication to TNF inhibitor therapy.

The case report is an example of a common scenario in clinical care, when a patient with inflammatory bowel disease and cancer has to be concomitantly treated for both conditions. While the case illustrates it is possible to use TNF inhibitors in this scenario, the follow-up is three years and is relatively short.

P- Reviewers: Bessissow T, Meucci G, Tanida S S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Barreiro-de Acosta M, Lorenzo A, Dominguez-Muñoz JE. Adalimumab in ulcerative colitis: two cases of mucosal healing and clinical response at two years. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3814-3816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, D’Haens G, Wolf DC, Kron M, Tighe MB, Lazar A, Thakkar RB. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:257-265.e1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 817] [Cited by in RCA: 943] [Article Influence: 72.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Laclotte C, Roblin X, Bigard MA. Adalimumab induction therapy for ulcerative colitis with intolerance or lost response to infliximab: an open-label study. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2328-2332. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Afif W, Leighton JA, Hanauer SB, Loftus EV, Faubion WA, Pardi DS, Tremaine WJ, Kane SV, Bruining DH, Cohen RD. Open-label study of adalimumab in patients with ulcerative colitis including those with prior loss of response or intolerance to infliximab. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1302-1307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Taxonera C, Estellés J, Fernández-Blanco I, Merino O, Marín-Jiménez I, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Saro C, García-Sánchez V, Gento E, Bastida G. Adalimumab induction and maintenance therapy for patients with ulcerative colitis previously treated with infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:340-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Strangfeld A, Hierse F, Rau R, Burmester GR, Krummel-Lorenz B, Demary W, Listing J, Zink A. Risk of incident or recurrent malignancies among patients with rheumatoid arthritis exposed to biologic therapy in the German biologics register RABBIT. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kouklakis G, Efremidou EI, Pitiakoudis M, Liratzopoulos N, Polychronidis ACh. Development of primary malignant melanoma during treatment with a TNF-α antagonist for severe Crohn’s disease: a case report and review of the hypothetical association between TNF-α blockers and cancer. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2013;7:195-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hudesman D, Lichtiger S, Sands B. Risk of extraintestinal solid cancer with anti-TNF therapy in adults with inflammatory bowel disease: review of the literature. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:644-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dixon WG, Watson KD, Lunt M, Mercer LK, Hyrich KL, Symmons DP. Influence of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy on cancer incidence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have had a prior malignancy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:755-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Saba NS, Kosseifi SG, Charaf EA, Hammad AN. Adalimumab-induced acute myelogenic leukemia. South Med J. 2008;101:1261-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bongartz T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, Buchan I, Matteson EL, Montori V. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006;295:2275-2285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1816] [Cited by in RCA: 1814] [Article Influence: 95.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bongartz T, Warren FC, Mines D, Matteson EL, Abrams KR, Sutton AJ. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of malignancies: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1177-1183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Siegel CA, Marden SM, Persing SM, Larson RJ, Sands BE. Risk of lymphoma associated with combination anti-tumor necrosis factor and immunomodulator therapy for the treatment of Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:874-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 402] [Cited by in RCA: 381] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wong AK, Kerkoutian S, Said J, Rashidi H, Pullarkat ST. Risk of lymphoma in patients receiving antitumor necrosis factor therapy: a meta-analysis of published randomized controlled studies. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31:631-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bickston SJ, Lichtenstein GR, Arseneau KO, Cohen RB, Cominelli F. The relationship between infliximab treatment and lymphoma in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1433-1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Brown SL, Greene MH, Gershon SK, Edwards ET, Braun MM. Tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy and lymphoma development: twenty-six cases reported to the Food and Drug Administration. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:3151-3158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 473] [Cited by in RCA: 434] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ziakas PD, Giannouli S, Tzioufas AG, Voulgarelis M. Lymphoma development in a patient receiving anti-TNF therapy. Haematologica. 2003;88:ECR25. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Aksu K, Donmez A, Ertan Y, Keser G, Inal V, Oder G, Tombuloglu M, Kabasakal Y, Doganavsargil E. Hodgkin’s lymphoma following treatment with etanercept in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Int. 2007;28:185-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lee JJ, Mann JA, Blauvelt A. Papillary thyroid carcinoma in a patient with severe psoriasis receiving adalimumab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:999-1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Carlesimo M, Mari E, La Pietra M, Orsini D, Pranteda G, Pranteda G, Grimaldi M, Arcese A. Occurrence of salivary gland tumours in two patients treated with biological agents. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2012;25:297-300. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Datta G, Maisnam D. Lymphoma and metastatic breast cancer presenting with palpable axillary and inguinal lymphadenopathy in a 40-year-old man with rheumatoid arthritis on anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Carlesimo M, La Pietra M, Arcese A, Di Russo PP, Mari E, Gamba A, Orsini D, Camplone G. Nodular melanoma arising in a patient treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonists. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1234-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kowalzick L, Eickenscheidt L, Komar M, Schaarschmidt E. [Long term treatment of psoriasis with TNF-alpha antagonists. Occurrence of malignant melanoma]. Hautarzt. 2009;60:655-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Betteridge JD, Veerappan GR. Pulmonary carcinoid tumor in a patient on adalimumab for Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:E29-E30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nemes B, Podder H, Járay J, Dabasi G, Lázár L, Schaff Z, Sótonyi P, Perner F. Primary hepatic carcinoid in a renal transplant patient. Pathol Oncol Res. 1999;5:67-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Colombel JF, Loftus EV, Tremaine WJ, Egan LJ, Harmsen WS, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The safety profile of infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease: the Mayo clinic experience in 500 patients. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:19-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 649] [Cited by in RCA: 621] [Article Influence: 29.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wolfe F, Michaud K. Biologic treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of malignancy: analyses from a large US observational study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2886-2895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 382] [Cited by in RCA: 381] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Askling J, Fored CM, Brandt L, Baecklund E, Bertilsson L, Feltelius N, Cöster L, Geborek P, Jacobsson LT, Lindblad S. Risks of solid cancers in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and after treatment with tumour necrosis factor antagonists. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1421-1426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Askling J, Fored CM, Baecklund E, Brandt L, Backlin C, Ekbom A, Sundström C, Bertilsson L, Cöster L, Geborek P. Haematopoietic malignancies in rheumatoid arthritis: lymphoma risk and characteristics after exposure to tumour necrosis factor antagonists. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1414-1420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 317] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Watson KD, Dixon WG, Hyrich KL, Lunt M, Symmons DP, Silman AJ. Influence on the anti-TNF therapy and previous malignancy on cancer incidence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA): results from the BSR biologics register [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:512. |

| 31. | Madhusudan S, Foster M, Muthuramalingam SR, Braybrooke JP, Wilner S, Kaur K, Han C, Hoare S, Balkwill F, Talbot DC. A phase II study of etanercept (Enbrel), a tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitor in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6528-6534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Madhusudan S, Muthuramalingam SR, Braybrooke JP, Wilner S, Kaur K, Han C, Hoare S, Balkwill F, Ganesan TS. Study of etanercept, a tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor, in recurrent ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5950-5959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Tsimberidou AM, Thomas D, O’Brien S, Andreeff M, Kurzrock R, Keating M, Albitar M, Kantarjian H, Giles F. Recombinant human soluble tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor (p75) fusion protein Enbrel in patients with refractory hematologic malignancies. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2002;50:237-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Brown ER, Charles KA, Hoare SA, Rye RL, Jodrell DI, Aird RE, Vora R, Prabhakar U, Nakada M, Corringham RE. A clinical study assessing the tolerability and biological effects of infliximab, a TNF-alpha inhibitor, in patients with advanced cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1340-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Fulchiero GJ, Salvaggio H, Drabick JJ, Staveley-O’Carroll K, Billingsley EM, Marks JG, Helm KF. Eruptive latent metastatic melanomas after initiation of antitumor necrosis factor therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:S65-S67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Cassaday RD, Malik JT, Chang JE. Regression of Hodgkin lymphoma after discontinuation of a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor for Crohn’s disease: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2011;11:289-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lees CW, Ironside J, Wallace WA, Satsangi J. Resolution of non-small-cell lung cancer after withdrawal of anti-TNF therapy. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:320-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Gardner RC, Feinerman AE, Kantrowitz PA, Gottblatt S, Loewenstein MS, Zamcheck N. Serial carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) blood levels in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Dig Dis. 1978;23:129-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Loewenstein MS, Zamcheck N. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels in benign gastrointestinal disease states. Cancer. 1978;42:1412-1418. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Ledingham J, Deighton C. Update on the British Society for Rheumatology guidelines for prescribing TNFalpha blockers in adults with rheumatoid arthritis (update of previous guidelines of April 2001). Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005;44:157-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Brar A, Hiebert T, El-Gabalawy H. Unresolved issue: should patients with RA and a history of malignancy receive anti-TNF therapy? Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3:120-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |