Published online Apr 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i16.4822

Revised: December 31, 2013

Accepted: January 20, 2014

Published online: April 28, 2014

Processing time: 153 Days and 18.7 Hours

Solitary Peutz-Jeghers type hamartomatous polyp is rare. It is considered to be related to a variant Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) and may be a separate disease entity. A 50-year-old man was referred to our hospital with a diagnosis of intussusception in the terminal ileum and underwent segmental ileal resection with appendectomy. We identified a 3.5-cm diameter polyp arising from the appendix with ingrowth into the terminal ileum. The polyp was confirmed to be a hamartomatous polyp of Peutz-Jeghers-type, histologically. However, the patient had no characteristic manifestations of PJS such as mucocutaneous pigmentation and family history. There are few reports of appendiceal hamartomatous polyp in PJS patients and solitary appendiceal hamartomatous polyp is even rarer. Also, rather than telescoping, ours is the first reported intussuscepted lesion, to the best of our knowledge.

Core tip: Intussusception arising from various leading points can cause intestinal obstruction. We experienced a case of solitary Peutz-Jeghers-type hamartomatous polyp in the appendix. This is an extremely rare condition with an unusual ingrowth characteristic. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first case of a solitary appendiceal hamartomatous polyp with an ingrowing pattern. Although there are limitations, this case could serve as a reference for diagnostic and management decisions in future similar cases.

- Citation: Choi CI, Kim DH, Jeon TY, Kim DH, Shin NR, Park DY. Solitary Peutz-Jeghers-type appendiceal hamartomatous polyp growing into the terminal ileum. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(16): 4822-4826

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i16/4822.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i16.4822

Hamartomatous polyp is often associated with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS), which is a rare inherited autosomal dominant disorder characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation[1]. Solitary hamartomatous polyp has been considered a variant or a separate disease entity without the features of PJS[2]. Such hamartomatous polyps occur predominantly in the small bowel, colon, and stomach, in decreasing frequency, and they rarely arise from the appendix[3]. We report an experience of a solitary appendiceal hamartomatous polyp without the characteristic features of PJS, that led to bowel obstruction by ingrowing through direct adhesion to the terminal ileum rather than by telescoping. This is the first case, to our knowledge, of solitary Peutz-Jeghers-type hamartomatous polyp with ingrowth into the terminal ileum.

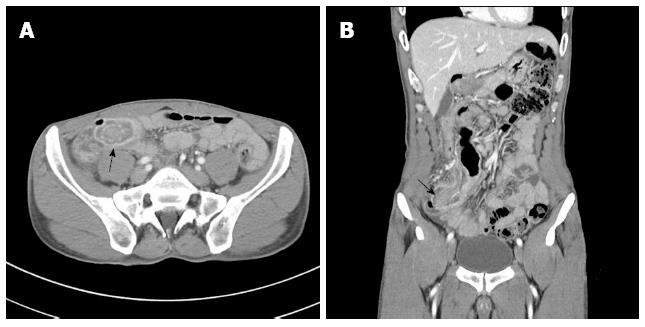

A 50-year-old man presented to our emergency room complaining of right lower quadrant pain, abdominal discomfort, and bilious vomiting for 3 d. He was diagnosed with intussusception at a local medical clinic. A colonoscopy performed 4 years previously showed no abnormal findings, the patient had no past history of disease, and his vital signs were normal on arrival. On physical examination, mild peristaltic pain and tenderness was observed in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen without rebound tenderness. Mucocutaneous pigmentation of the perioral region, buccal mucosa, hands and feet was absent. Standard laboratory tests were unremarkable except for a mildly elevated white blood cell count of 11480/μL. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a 2.4-cm diameter intussusception due to a polypoid mass and multiple lymph nodes surrounding the lesion (Figure 1). We didn’t perform esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

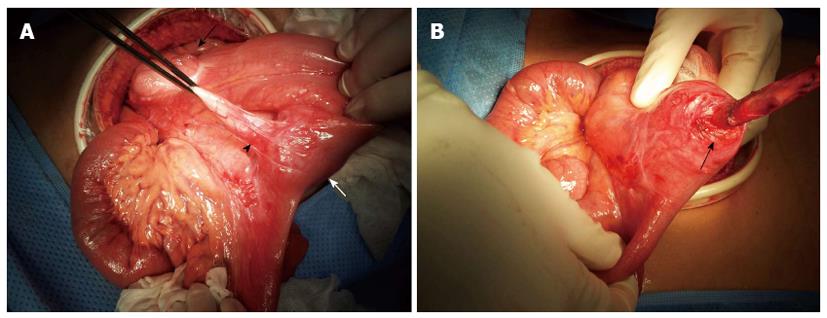

Emergent exploratory laparotomy with midline incision was performed under general anesthesia. Intraoperatively, a solitary firm mass of approximately 4 cm diameter was palpable within the terminal ileum 20 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve. The appendix was attached to the ileal serosa below the mass lesion (Figure 2A). We attempted to dissect the appendix tip but because the appendix tip entered the ileum, it was not entirely separable from the terminal ileum (Figure 2B). Therefore, we divided the appendix base from the cecum and performed an en-bloc resection, which included segmental resection of 15 cm of the terminal ileum. An end-to-end anastomosis of the ileum completed the procedure.

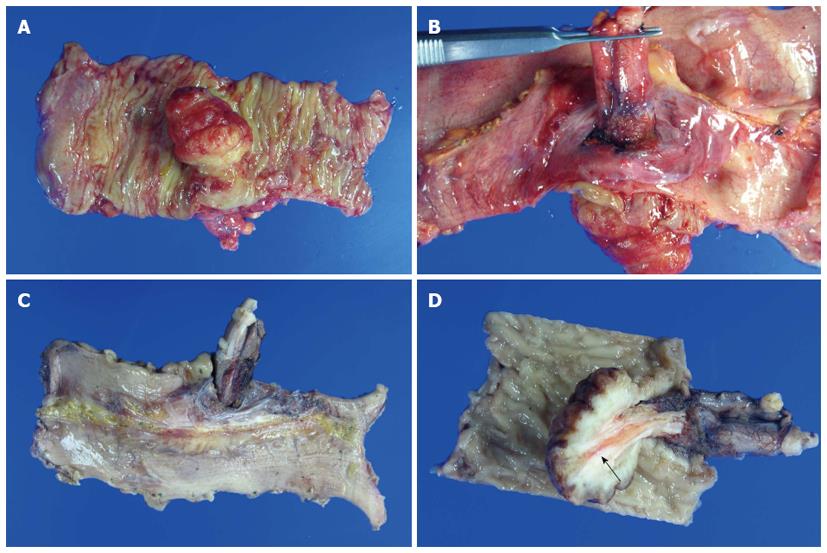

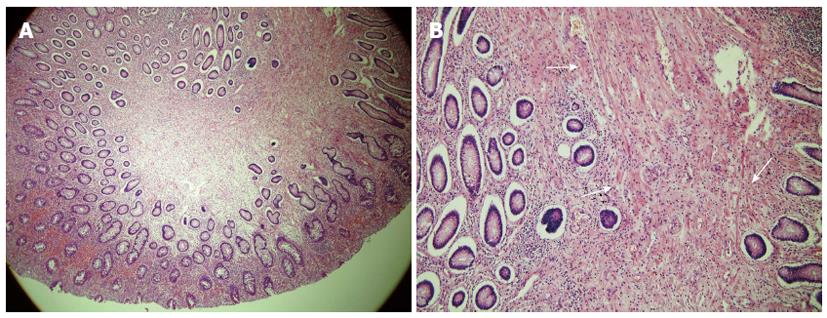

The mass was pathologically identified as a hamartomatous polyp of 3.5 cm × 3.0 cm with surface ulceration. Grossly, the appendix was intussuscepted into the terminal ileum. Tissue cross section revealed invagination of the appendix into the resected terminal ileum, from the ileal external surface (Figure 3). Microscopic examination of the polyp revealed extensive smooth-muscle proliferation with an arborized pattern in the lamina propria (Figure 4). These smooth-muscle bundles were covered with hyperplastic mucosa and we were able to identify the appendiceal lumen penetrating the ileal polyp under microscopy. There were eight regional lymph nodes involved, which showed reactive hyperplasia without tumor metastasis, histopathologically.

Patient resumed an oral liquid diet on postoperative day 3 and he was discharged at day 6 postoperatively without any complications. There was no recurrence or remarkable findings during 2 years of postoperative follow-up.

PJS is an inherited, autosomal dominant polypoid syndrome with a prevalence of one in 100000 individuals. The disease is characterized by gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyps and mucocutaneous pigmentation on perioral buccal mucosa, and hands and feet[1]. Hamartomatous polyps can occur throughout the gastrointestinal tract, but the small intestine is the most commonly affected site at 64%. These polyps cause abdominal pain, intestinal bleeding, and obstruction[3]. Our patient, who had no family history or juvenile operation history, visited our hospital because of acute onset abdominal pain in the right lower quadrant as a result of intestinal obstruction due to intussusception. Characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation was not observed in this case, although it is present in more than approximately 90% of patients[4]. Solitary hamartomatous polyp was reported by Kuwano et al[5] in 1989. It is considered to be either an incomplete variant of PJS or a separate disease entity because of the absence of external features and family history. This solitary lesion has been termed Peutz-Jeghers-type polyp[2,5,6].

Hamartomatous polyps are often diagnosed incidentally on endoscopy. Although abdominal CT findings in PJS patients are nonspecific, in cases with intestinal obstruction by intussusception or a large polyp, abdominal CT or gastrointestinal series can be diagnostic. Because hamartomatous polyps are grossly difficult to distinguish from other hamartomatous polyposis syndromes on endoscopy, diagnostic confirmation depends on histopathology as well as the various clinical manifestations[1].

Microscopically, Peutz-Jeghers-type polyp shows extensive smooth-muscle proliferation and an elongated arborized pattern of polyp formation, and it is distinguishable from adenomatous polyps that can be seen in familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome[7]. In our patient, preoperative abdominal CT revealed a “target sign” at the terminal ileum and we were able to identify the intestinal obstruction due to intussusception by the polypoid mass. The postoperative histopathologic results confirmed a hamartomatous polyp.

Miyahara et al[8] reported a case of intussusception arising from an appendiceal hamartomatous polyp in a PJS patient with anemia and described the appendix invaginating into the cecum in their case[8]. In general, bowel intussusception is caused by telescoping of the proximal bowel (intussusceptum) into the adjacent distal bowel segment (intussuscipiens)[9]. Appendiceal intussusceptions occur by intraluminal or intramural irritation caused by space-occupying lesions such as appendiceal fecalith, lymphoid hyperplasia, endometriosis, carcinoid tumor, adenoma, or adenocarcinoma. The most common type of appendiceal intussusception is appendico-cecal or ceco-colic[8,10]. The symptoms are very similar to those of acute appendicitis.

Our case differs from previous cases in that the intussusception was caused by direct ingrowth of the appendiceal tip into the terminal ileal lumen, rather than by a typical telescoping mechanism. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first case with this rare presentation. Although it is difficult to explain the exact mechanism of the ingrowth in this case, in considering the macro- and microscopic findings, we assume that the hamartomatous polyp arose from the appendiceal tip attached to the serosa of the terminal ileum, and growth of the polyp led to forced entry into the ileal lumen. If it was an ileal hamartomatous polyp, the normal appendix would not be expected to react with an ileal mass to the degree seen in this case. Also, we observed that the appendiceal lumen ran continuously from the external appendix to within the hamartomatous polyp and this was confirmed, microscopically. If the normal appendix was intussuscepted into ileal polyp, we could separate the appendix from the polyp with comparative ease. But appendix and polyp were unseparable. We think that strong tissue interaction between appendix and distal ileum is one of evidence which the polyp is originated from the appendix. Therefore, the primary lesion in our case ought to be the appendix.

Appendiceal tumors are rare, reportedly occurring in < 2% of all appendectomies, and hamartomatous polyps in the appendix are even rarer[11,12]. There have been sporadic reports of appendiceal hamartomatous polyps confirmed in PJS patients; however, there are only two case reports of solitary Peutz-Jeghers-type hamartomatous polyps in the appendix without PJS, to our knowledge [13,14].

Hamartomatous polyp is considered a benign lesion, but when it is associated with PJS, the risk of malignancy is increased in gastrointestinal and extra-intestinal sites[15]. Treatment for hamartomatous polyp can include endoscopic resection, polypectomy via enterotomy, and bowel resection. But in patients with PJS, short bowel syndrome can occur due to repeated bowel resection because 30% of these patients require laparotomy and 50% require more than two abdominal surgeries[16,17]. Therefore, less invasive treatment had to be chosen in those patients. In asymptomatic patients, observation is sufficient, but close follow-up is required because of complications such as multiple cancer, intestinal obstruction, and bleeding. In our case, preoperative abdominal CT definitively revealed the leading point causing the intussusception at the terminal ileum. Because the lesion was not considered to be in spontaneous remission, we performed exploratory laparotomy.

Preventive appendectomy during surgery for other disease is controversial but we believe that if an appendiceal mass is identified pre- or intraoperatively, resection is essential to determine additional treatment after histologic confirmation[18]. The final histopathological result in this patient occurred following discharge. We attempted to identify mucocutaneous pigmentation and family history to find out an association with PJS, but there were no such characteristic findings of PJS in this patient. For that reason we did not perform postoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy or colonoscopy. This is able to be a limitation of our follow-up strategy. Surveillance of PJS often follows experts’ opinion because of the lack of randomized controlled trials, and in 2006, European experts established age-specific guidelines for the management of these patients[19].

Appendiceal hamartomatous polyp in our patient had the distinctive aspect of morphogenesis. Because it did not correspond with the conventional concept of the mechanism of intussusception, it was difficult to determine grossly whether this was a case of intussusception or ingrowth. Because definite diagnosis depends on the histopathological finding after resection, the patient with symptomatic mass may needs the resection through the laparotomy or endoscopic approach. Based on histology, periodic surveillance or additional treatment can be required. We believe that ours are a very rare case, clinically, and the first report of its kind to the best of our knowledge.

Mild peristaltic pain and tenderness was observed as main symptoms in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen without rebound tenderness.

Main clinical diagnosis was acute appendicitis.

Authors’ had to rule out intestinal obstruction because of abdominal discomfort and bilious vomiting.

Blood sample tests were unremarkable except for a mildly elevated white blood cell count of 11480/μL.

Intussusception due to 2.4-cm diameter polypoid mass was identified in distal ileum through the abdominal computed tomography.

Histopathologic finding (hematoxylin and eosin staining) revealed a hamartomatous polyp of 3.5 cm × 3.0 cm with surface ulceration.

The patient underwent the segmental resection of distal ileum with appendectomy.

The solitary Peutz-Jegher-type polyp is considered to be either an incomplete variant of Peutz-Jegher syndrome or a separate disease entity because of the absence of characteristic external features and family history.

So based on histology, periodic surveillance or additional treatment can be required because hamartomatous polyp has malignant potential when it is associated with Peutz-Jegher syndrome.

Among the case reports, this paper is impressive and informative.

P- Reviewers: Chan KWE, Lee WK, Lai YC, Matsuda A S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Kopacova M, Tacheci I, Rejchrt S, Bures J. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: diagnostic and therapeutic approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5397-5408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Acea Nebril B, Taboada Filgueira L, Parajó Calvo A, Gayoso García R, Gómez Rodríguez D, Sánchez González F, Sogo Manzano C. Solitary hamartomatous duodenal polyp; a different entity: report of a case and review of the literature. Surg Today. 1993;23:1074-1077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Utsunomiya J, Gocho H, Miyanaga T, Hamaguchi E, Kashimure A. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: its natural course and management. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1975;136:71-82. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Erbe RW. Inherited gastrointestinal-polyposis syndromes. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:1101-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kuwano H, Takano H, Sugimachi K. Solitary Peutz-Jeghers type polyp of the stomach in the absence of familial polyposis coli in a teenage boy. Endoscopy. 1989;21:188-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kitaoka F, Shiogama T, Mizutani A, Tsurunaga Y, Fukui H, Higami Y, Shimokawa I, Taguchi T, Kanematsu T. A solitary Peutz-Jeghers-type hamartomatous polyp in the duodenum. A case report including results of mutation analysis. Digestion. 2004;69:79-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bentley BS, Hal HM. Obstructing hamartomatous polyp in peutz-jeghers syndrome. Case Rep Radiol. 2013;2013:595341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Miyahara M, Saito T, Etoh K, Shimoda K, Kitano S, Kobayashi M, Yokoyama S. Appendiceal intussusception due to an appendiceal malignant polyp--an association in a patient with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: report of a case. Surg Today. 1995;25:834-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Azar T, Berger DL. Adult intussusception. Ann Surg. 1997;226:134-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 648] [Cited by in RCA: 666] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Coulier B, Pestieau S, Hamels J, Lefebvre Y. US and CT diagnosis of complete cecocolic intussusception caused by an appendiceal mucocele. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:324-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Deans GT, Spence RA. Neoplastic lesions of the appendix. Br J Surg. 1995;82:299-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Connor SJ, Hanna GB, Frizelle FA. Appendiceal tumors: retrospective clinicopathologic analysis of appendiceal tumors from 7,970 appendectomies. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:75-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 402] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Iida H, Inamori M, Sekino Y, Endo H, Akiyama T, Fujita K, Takahashi H, Yoneda M, Kobayashi N, Abe Y. Acute appendicitis associated with Peutz-Jeghers-type hamartoma of the appendix. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2832-2833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nozoe T, Mori E, Iguchi T, Kohno M, Maeda T, Matsukuma A, Sueishi K, Ezaki T. Pedunculated hamartomatous polyp of the appendix: report of a case. Surg Today. 2013;43:191-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Giardiello FM, Welsh SB, Hamilton SR, Offerhaus GJ, Gittelsohn AM, Booker SV, Krush AJ, Yardley JH, Luk GD. Increased risk of cancer in the Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1511-1514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 577] [Cited by in RCA: 512] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Edwards DP, Khosraviani K, Stafferton R, Phillips RK. Long-term results of polyp clearance by intraoperative enteroscopy in the Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:48-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hinds R, Philp C, Hyer W, Fell JM. Complications of childhood Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: implications for pediatric screening. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:219-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bucher P, Mathe Z, Demirag A, Morel P. Appendix tumors in the era of laparoscopic appendectomy. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1063-1066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Giardiello FM, Trimbath JD. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and management recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:408-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |