Published online Mar 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i12.3383

Revised: December 31, 2013

Accepted: January 20, 2014

Published online: March 28, 2014

Processing time: 159 Days and 14.3 Hours

Here, we report on a case of acute phlegmonous gastritis (PG) complicated by delayed perforation. A 51-year-old woman presented with severe abdominal pain and septic shock symptoms. A computed tomography scan showed diffuse thickening of the gastric wall and distention with peritoneal fluid. Although we did not find definite evidence of free air on the computed tomography (CT) scan, the patient’s clinical condition suggested diffuse peritonitis requiring surgical intervention. Exploratory laparotomy revealed a thickened gastric wall with suppurative intraperitoneal fluid in which Streptococcus pyogenes grew. There was no evidence of gastric or duodenal perforation. No further operation was performed at that time. The patient was conservatively treated with antibiotics and proton pump inhibitor, and her condition improved. However, she experienced abdominal and flank pain again on postoperative day 10. CT and esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed a large gastric ulcer with perforation. Unfortunately, although the CT showed further improvement in the thickening of the stomach and the mucosal defect, the patient’s condition did not recover until a week later, and an esophagogastroduodenoscopy taken on postoperative day 30 showed suspected gastric submucosal dissection. We performed total gastrectomy as a second operation, and the patient recovered without major complications. A pathological examination revealed a multifocal ulceration and necrosis from the mucosa to the serosa with perforation.

Core tip: Acute phlegmonous gastritis (PG) is a rare and often fatal condition that is characterized by bacterial infection. Patients with PG can present with abdominal pain, abdominal distension, nausea, vomiting, fever, and signs of infection. Computed tomography is useful in the early diagnosis of PG. However, because of the rarity of this disease, the diagnosis and choice of appropriate treatment is difficult. Here, we report a case of acute PG complicated by delayed perforation during conservative treatment after explorative laparotomy without gastric resection.

- Citation: Min SY, Kim YH, Park WS. Acute phlegmonous gastritis complicated by delayed perforation. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(12): 3383-3387

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i12/3383.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i12.3383

Phlegmonous gastritis (PG) is a rare and often fatal disease that is characterized by bacterial infection of the stomach. Patients present with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, and signs of infection. The most common pathogens related to PG are members of the Streptococcus species. Streptococcus accounts for approximately 68% to 75% of all PG cases[1,2]. Although the pathogenesis is not completely known, predisposing factors, such as mucosal injury, immunocompromise, alcohol use, and a history of gastritis have been hypothesized as being important factors[2-4]. However, approximately 50% of the patients who develop PG were previously healthy. Because of its rarity, the proper treatment of PG is not precisely known; therefore, treatment decisions are difficult. We present a case of acute PG complicated by delayed perforation resulting from unsuccessful conservative treatment.

A previously healthy 51-year-old woman was brought to the emergency room. She presented with severe abdominal pain and vomiting. There was no history of alcoholism or other diseases. One day prior to admission, she vomited and experienced upper abdominal pain after dinner; as a result, she visited another hospital. She was diagnosed with usual gastritis and underwent treatment with an H2 blocker. Although she took a pill, the symptoms worsened. Upon examination, the bowel sounds were hypoactive, the diffuse abdomen was tender to palpation, and there was muscle guarding. Her blood pressure was 70/40 mmHg, her heart rate was 122 beats per minute, and her body temperature 36.2 °C.

The patient’s laboratory results upon admission were as follows: white blood cell count (WBC), 2.9 × 103/μL (normal, 4-10 × 103/μL), with 92.6% segmented neutrophils (50%-70%); hemoglobin, 14.3 g/dL (12-16 g/dL); platelet count, 308 × 103/μL (150-400 × 103/μL); aspartate transaminase, 25 U/L (about 40 U/L); alanine transaminase, 18 U/L (about 40 U/L); amylase, 85 U/L (25-125 U/L); and C-reactive protein, 26.03 mg/dL (about 0.3 mg/dL).

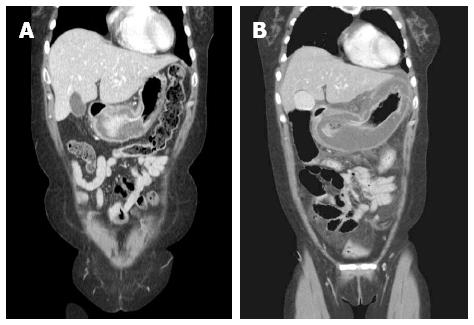

Computed tomography (CT) revealed a diffusely distended and thickened whole stomach with intraperitoneal fluid. Compared with a CT scan performed earlier at another hospital, gastric distention and wall thickening had aggravated remarkably (Figure 1). Although we did not find definite evidence of free air on the CT scan, the patient’s clinical condition suggested diffuse peritonitis requiring surgical intervention. Our preoperative diagnosis was peritonitis with septic shock. We could not exclude bowel perforation, including gastric wall perforation. We suspected that the cause of the gastric distension was inflammation caused by a hidden, sealed gastric perforation. Because her situation was emergent, the patient underwent aggressive fluid resuscitation and was administered broad-spectrum antibiotics. She was taken to the operating room for an explorative laparotomy without other examinations, such as diagnostic endoscopy. Upon exploration, the stomach was abnormally edematous and appeared pale. The surface of the stomach was covered with whitish fibrinous exudates. The intraperitoneal cavity was filled with large amounts of turbid, straw-colored fluid. The peritoneal fluid was sampled for microbial culture analysis. There was no evidence of gastric or duodenal perforation. The remaining bowel appeared normal upon inspection. Massive irrigation was performed, and Jackson-Pratt drains were inserted. No further operation was performed at that time. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for management.

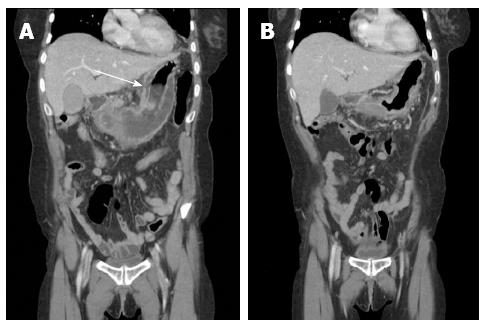

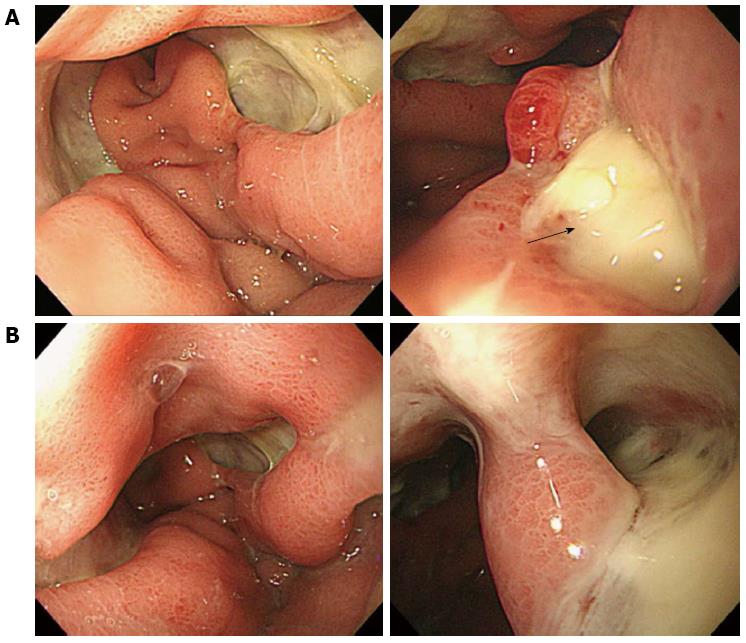

For the initial 48 h, the patient received intensive support with a cardiac dose of epinephrine, norepinephrine, and fluid to treat septic shock. Although the neutropenia worsened during first 12 postoperative hours, it normalized by postoperative day (POD) 2. After 2 d in the intensive care unit, the patient remained in the general ward for an additional 40 d. She was administered intravenous moxifloxacin for 10 d and piperacillin/tazobactam for 18 d. We prescribed an H2 blocker and administered it with a proton pump inhibitor. Streptococcus pyogens grew from the peritoneal fluid culture. At POD 4, with parenteral nutrition support, the patient started to drink sips of water. After a few days, she was able to consume a liquid diet. Because the patient complained of mild to moderate left flank pain, we performed a CT scan and laboratory tests on POD 9 (Figure 2 and Table 1). The CT scan revealed improved thickening of the gastric wall, but the lesser curvature of the stomach exhibited focal non-enhanced mucosal lesions. This lesion suggested a suspicious focal wall disruption, but no free air was observed. The patient was treated with parenteral nutrition support. Because we provided parenteral nutrition and regular nutritional status assessments were performed, the patient’s nutritional status was well maintained. On POD 23, the patient underwent an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) that revealed a large gastric ulcer and a suspicious perforation site on the high body posterior wall of the stomach (Figure 3). However, because there was no definite evidence of free perforation and the perforated site was covered with fibrotic tissue, we decided to wait until the perforation site healed naturally. Unfortunately, although the CT showed further improvement in the thickening of the stomach and the mucosal defect, the patient’s condition did not recover until a week later, and an EGD taken on POD 30 showed suspected gastric submucosal dissection (Figures 2 and 3). We decided to perform a second operation. The gastrectomy revealed that there was no wall dissection, but a thin fibrotic tissue covering a 1.5 cm perforation was found on the high body of the stomach. This perforation site was consistent with prior CT findings. General edema and focal fragile tissue of the wall were also revealed. Because of the gastric wall findings, a total gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y anastomosis were performed.

| Upon admission | Postoperative | POD 2 | POD 9 | POD 24 | |

| WBC (4.0 × 103-10.0 × 103/μL) | 2060 | 520 | 10290 | 14340 | 5980 |

| Hemoglobin (12-16 g/μL) | 13.7 | 13.9 | 12.6 | 13.1 | 10.1 |

| Platelets (150 × 103-350 × 103/μL) | 299 | 169 | 94 | 423 | 344 |

| Segmented neutrophils (40%-74%) | 92 | 95.2 | 85 | 74.8 | |

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.1 | |

| AST (about 40 U/L) | 25 | 104 | 53 | 57 | 33 |

| ALT (about 40 U/L) | 18 | 65 | 45 | 57 | 33 |

| Amylase (25-125 U/L) | 85 | 124 | 29 | 220 | 155 |

| CRP (about 0.3 mg/μL) | 26 | 18.9 | 6.1 | 7.5 |

Gross examination of the specimen revealed a serosal perforated area with diffuse exudative materials. The mucosal surfaces showed a multifocal ulceration and diffuse red-brown discoloration with marked edematous change. Microscopic examination revealed ulceration with necrosis and acute and chronic inflammatory infiltrate from the mucosa to the serosa.

Postoperatively, the patient recovered without complications and was discharged on POD 10 following the second operation. She resumed her regular diet and no longer required antibiotics.

Acute phlegmonous gastritis is a rare and potentially fatal condition. It is an acute infection of the stomach wall, submucosa, and muscularis propria by pyogenic bacteria[5-9]. The etiology of PG is unclear. Predisposing factors, such as alcoholism, mucosal injury, immunocompromise, acquired immune deficiency syndrome, gastric hemorrhage, pregnancy, neutropenia after chemotherapy, and endoscopic procedure have been reported[6,8,10-13]. Our patient was healthy and had no predisposing factors.

The clinical presentation of PG is nonspecific. The symptoms include epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, and less often, diarrhea and fever. The usual presentation is severe epigastric pain. Sepsis and multiple organ failure have been frequently reported[4,14]. The onset of PG is usually rapid[11]. Moreover, the disease’s progression is rapid. PG may follow a rapidly fulminating course, with rapid onset, marked toxemia, and early peripheral circulatory collapse[15]. In our case, thickening of the gastric wall was rapidly aggravated for only a day.

PG can be diagnosed by endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasound, and CT scan[15-18]. Although an accurate diagnosis is difficult using examination tools alone, it is possible after appropriate clinical correlation. Because PG is extremely rare and has an atypical presentation, a clinician can misdiagnose it despite performing medical examinations, including CT. Our patient was not administered antibiotics at the other hospitals she first visited; instead, she received a diagnosis of usual gastritis.

PG pathogens are identified from cultures of the peritoneal fluid, gastric aspirates or tissue. Hemolytic streptococcus is the most frequently found organism. Pneumococci, staphylococci, Proteus vulgaris, Escherichia coli, Clostridium welchii, and Bacteroides subtilis are also found[6,15]. PG resulted in the deaths of 41% of the PG patients reviewed, with Streptococcus found in 53.3% of the patients who died. Streptococcus was not only the major organism identified but also the most common organism associated with a fatal outcome[6].

The optimal treatment for PG is controversial. Starr et al[19] reported that the overall mortality rate was 48% after 1945 (when antibiotics became available). Seventy-five percent of the patients died after subtotal gastrectomy, and there was a 50% mortality rate for the patients who were treated with antibiotics only. Kim et al[6] reviewed 36 PG cases from 1975 to 2003. They reported that the mortality rate for patients with surgical resection was 20%, compared with 50% in patients who were treated medically. The mortality rate for localized disease was 10% compared with 54% in patients with diffuse disease. In a review of the 9 PG cases in Korea from 1980 to 2011, Kim et al[20] noted that the mortality rate for patients undergoing surgery was 67%; for patients treated medically, it was 0%. Starr et al[19] recommended treatment options. Subtotal gastrectomy is feasible for the chronic form of PG, and early recognition and prompt intensive supportive management are available for the acute form of PG. More recently, total gastrectomy has not been recommended in septic conditions because of high morbidity and mortality, and localized resections are recommended when possible[4,11]. Resection of the stomach is mainly indicated for complications, including perforation. If operative exploration is undertaken, meticulous evaluation should be performed to exclude a perforation. Endoscopic insufflations should be considered when possible[1]. The extent and progress of the disease may be a key determination of successful survival and proper treatment choices. As in our case, delayed perforation of the stomach can occur with the diffuse form. The extent of the disease is predictable with CT. CT will reveal a thickened and hypodense gastric wall. Additionally, CT will reveal low-density areas showing peripheral rim enhancement, which is indicative of intramural abscess[6,21]. Therefore, if diffuse and advanced disease is suspected, resection of the stomach can be considered even when there is no perforation upon exploration. Additionally, if the clinical presentation worsens during conservative management, early evaluation, including CT or EGD, should be performed.

In conclusion, we report a case of acute PG complicated by delayed perforation. PG is a rare and challenging condition. However, proper and successful treatment and survival is possible when it is diagnosed early. We believe that performing early EGD and CT is helpful for both early diagnosis and detecting complications. Additionally, the key to selecting the proper treatment for PG is to precisely predict the extent of the disease.

A 51-year-old woman presented with severe abdominal pain and signs of septic shock.

Diffuse and severe abdominal tenderness and muscle guarding with hypotension.

Gastric perforation, bowel perforation and severe gastritis with infection.

WBC, 2.9 × 103/μL (normal: 4-10 × 103/μL), with 92.6% segmented neutrophils (50%-70%); platelet count, 308 × 103/μL (150-400 × 103/μL); CRP, 26.03 mg/dL (about 0.3 mg/dL); and liver function tests were within the normal limits.

Computed tomography (CT) showed diffuse thickening of the gastric wall and severe distention with peritoneal fluid.

Microscopic examination revealed ulceration with necrosis and acute and chronic inflammatory infiltrate from the mucosa to the serosa.

The patient was treated with total gastrectomy because of delayed complications.

Acute phlegmonous gastritis is a rare condition. It is an acute infection of the stomach wall, submucosa, and muscularis propria with pyogenic bacteria. The etiology of phlegmonous gastritis (PG) is unclear. Predisposing factors, such as alcoholism, mucosal injury, immunocompromise, acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), gastric hemorrhage, pregnancy, neutropenia after chemotherapy, and endoscopic procedure have been reported.

Acute phlegmonous gastritis is an acute infection of the stomach wall.

This study reports a case of acute PG complicated by delayed perforation. We believe that performing early esophagogastroduodenoscopy and CT is helpful for both early diagnosis and detecting complications. Additionally, the precise prediction of the extent of the disease is the key to selecting the proper treatment.

Because this is a rare disease, a case report is interesting. Proper evaluation and precise prediction of the extent of the disease is the key for successful treatment and survival.

P- Reviewers: Hsu CP, Lakatos PL, Xu Y S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Paik DC, Larson JD, Johnson SA, Sahm K, Shweiki E, Fulda GJ. Phlegmonous gastritis and group A streptococcal toxic shock syndrome in a patient following functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2010;11:545-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Miller AI, Smith B, Rogers AI. Phlegmonous gastritis. Gastroenterology. 1975;68:231-238. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Stein LB, Greenberg RE, Ilardi CF, Kurtz L, Bank S. Acute necrotizing gastritis in a patient with peptic ulcer disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:1552-1554. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Schultz MJ, van der Hulst RW, Tytgat GN. Acute phlegmonous gastritis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:80-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kavalar R, Skok P, Kramberger KG. Phlegmonous gastritis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2005;117:364-368. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Kim GY, Ward J, Henessey B, Peji J, Godell C, Desta H, Arlin S, Tzagournis J, Thomas F. Phlegmonous gastritis: case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:168-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ocepek A, Skok P, Virag M, Kamenik B, Horvat M. Emphysematous gastritis -- case report and review of the literature. Z Gastroenterol. 2004;42:735-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lee BS, Kim SM, Seong JK, Kim SH, Jeong HY, Lee HY, Song KS, Kang DY, Noh SM, Shin KS. Phlegmonous gastritis after endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2005;37:490-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Park CW, Kim A, Cha SW, Jung SH, Yang HW, Lee YJ, Lee HIe, Kim SH, Kim YH. A case of phlegmonous gastritis associated with marked gastric distension. Gut Liver. 2010;4:415-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zazzo JF, Troché G, Millat B, Aubert A, Bedossa P, Kéros L. Phlegmonous gastritis associated with HIV-1 seroconversion. Endoscopic and microscopic evolution. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:1454-1459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hommel S, Savoye G, Lorenceau-Savale C, Costaglioli B, Baron F, Le Pessot F, Lemoine F, Lerebours E. Phlegmonous gastritis in a 32-week pregnant woman managed by conservative surgical treatment and antibiotics. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1042-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Saito M, Morioka M, Kanno H, Tanaka S. Acute phlegmonous gastritis with neutropenia. Intern Med. 2012;51:2987-2988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Takeuchi M, Uno H, Matsuoka H, Maeda K, Marutsuka K, Sumiyoshi A, Tsuda K, Tsubouchi H. [Acute necrotizing gastritis associated with adult T-cell leukemia in the course of chemotherapy]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1995;22:289-292. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Kakkar N, Vasishta RK, Banerjee AK, Bhasin DK, Singhi S. Phlegmonous inflammation of gastrointestinal tract autopsy study of three cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1999;42:101-105. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Gerster JC. Phlegmonous gastritis. Ann Surg. 1927;85:668-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Iwakiri Y, Kabemura T, Yasuda D, Okabe H, Soejima A, Miyagahara T, Okadome K. A case of acute phlegmonous gastritis successfully treated with antibiotics. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:175-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Soon MS, Yen HH, Soon A, Lin OS. Endoscopic ultrasonographic appearance of gastric emphysema. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1719-1721. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Hu DC, McGrath KM, Jowell PS, Killenberg PG. Phlegmonous gastritis: successful treatment with antibiotics and resolution documented by EUS. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:793-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Starr A, Wilson JM. Phlegmonous gastritis. Ann Surg. 1957;145:88-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim NY, Park JS, Lee KJ, Yun HK, Kim JS. [A case of acute phlegmonous gastritis causing gastroparesis and cured with medical treatment alone]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2011;57:309-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sood BP, Kalra N, Suri S. CT features of acute phlegmonous gastritis. Clin Imaging. 2000;24:287-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |