Published online Jan 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.214

Revised: September 20, 2013

Accepted: October 19, 2013

Published online: January 7, 2014

Processing time: 228 Days and 15.3 Hours

AIM: To determine if early initiation of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy affects the need for dose escalation.

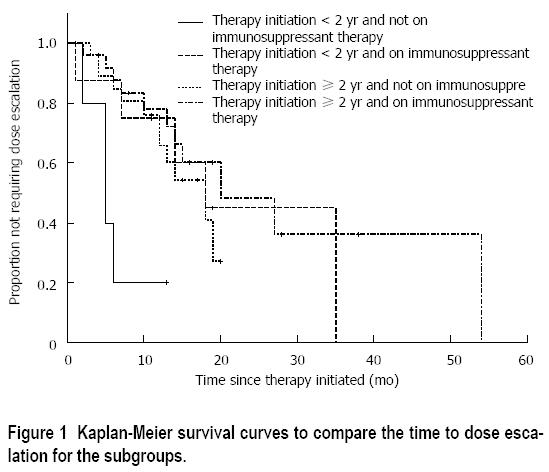

METHODS: This was a retrospective review of patients receiving infliximab therapy for Crohn’s disease (CD) at two outpatient gastroenterology clinics during July 2009 to October 2010. All patients included in the study were biologic agent naïve and had moderate to severe CD (Harvey Bradshaw index > 8). Patients were divided into groups based on length of time between diagnosis to therapy initiation and concurrent immunosuppressant therapy. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to compare the time to dose escalation for the four groups.

RESULTS: There were 68 patients, 51% female and 49% male, with an average age at diagnosis of 24.7 ± 11.9 years. The average age at infliximab initiation was 34.8 ± 14.8 years. Of the 68 patients, 19% initiated inflixiamb within 2 years of diagnosis, and 51% had concurrent immunosuppressant therapy at the time of therapy initiation. Fifty percent of patients required dose escalation and the median time from therapy initiation to dose escalation was 10 mo (interquartile range: 5.3-14.8). There was a statistically significant higher probability of requiring dose esclataion in patients who initiated biologic therapy within 2 years of diagnosis, without concurrent immunosuppressant therapy (P < 0.01).

CONCLUSION: Those who receive infliximab within 2 years of CD diagnosis require more intense immunosuppressant therapy than those who received infliximab later.

Core tip: Crohn’s disease patients who required infliximab therapy earlier (< 2 years) probably have a higher inflammatory burden of disease than those who require infliximab therapy later. Our results show that those who receive infliximab within 2 years of diagnosis require more intense immunosuppressant therapy to avoid dose escalation. This finding supports the importance of concurrent immunosuppressant therapy while on infliximab, as previously described by the SONIC trial.

- Citation: Lam MC, Lee T, Atkinson K, Bressler B. Time of infliximab therapy initiation and dose escalation in Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(1): 214-218

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i1/214.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.214

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α is a proinflammatory cytokine that has an important role in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease (CD)[1-4]. Serum and intestinal mucosa TNF-α levels are increased in CD, and disease activity is reduced by TNF-α-blocking agents[5,6]. Several meta-analyses have shown that anti-TNF-α agents are effective in induction and maintainence therapy, as well as in the treatment of fistulizing CD[7-13]. Moreover, the SONIC trial demonstrated that combination of azathioprine and infliximab is the most potent therapy to achieve steroid-free remission in CD patients[14].

Unfortunately, about 50% of patients receiving anti-TNF agents lose some or all of their initial therapeutic response, requiring dose escalation by increasing dosage or by shortening interval between infusions. Factors that influence dose escalation for anti-TNF therapy in CD are largely unknown. Gisbert et al[15] showed in a systematic review that CD treated with infliximab results in a 37% loss of response rate, requiring dose intensification, equivalent to an annual risk for loss of infliximab response at 13% per patient-year. The etiology for this loss of response is unclear because immunogenicity data do not suggest a correlation with clinical response[16,17]. Several studies have demonstrated that dose escalation by increasing dosage of infliximab (from 5 to 10 mg/kg), or shortening the interval between infusions from 8 to 6 wk is effective in reacquiring disease remission[16].

The factors that influence infliximab response duration are largely unknown. Our hypothesis is that early initiation of infliximab when disease is more likely to be inflammatory in its phenotype incurs a longer duration of response and requires less need for dose escalation.

The aim of the present study was to determine the relationship between time of infliximab initiation from disease diagnosis to the time of infliximab initiation to dose escalation.

This was a retrospective review of patients treated with infliximab for CD at two outpatient tertiary inflammatory bowel disease gastroenterology clinics from July 2009 to July 2010. Inclusion criteria were anti-TNF-naïve patients with moderate to severe CD as determined by Harvey Bradshaw Index (HBI) > 8 at the time of infliximab initiation, as assessed by individual gastroenterologists[18]. Patients receiving infliximab for treatment of fistulizing disease were excluded. Infliximab induction protocol was 5 mg/kg at 0, 2 and 6 wk, and every 8 wk thereafter. The decision for dose escalation was based on persistent HBI > 8 at three infusions or later in therapy to treat disease exacerbation.

Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed on five predetermined variables that were thought to have the most impact on infliximab response. These were sex, age at diagnosis (< 17, 17-40 and > 40 years), years between diagnosis and infliximab initiation (< or ≥ 2 years), behavior of disease, and concurrent immunosuppressant therapy (azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine or methotrexate). Disease behavior was described using the Montreal classification[19]. Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression were used to examine the impact of these variables on the proportion of patients requiring dose escalation within 12 mo. Patients who discontinued therapy before 12 mo or who were followed for < 12 mo without dose escalation were treated as unknown in terms of dose escalation for this analysis. The impact of these variables on the timing of dose escalation was further examined through Kaplan-Meier survival curve and Cox proportional hazards model. Patients who discontinued therapy before dose escalation were censored in the survival analysis.

Ninety patients were receiving infliximab during July 2009 to July 2010. Sixty-eight patients met the inclusion criteria. The following were excluded: seven patients with prior exposure to biologics; 13 with ulcerative colitis; and two with missing essential historical data. Forty-nine percent of patients were male, with an average age at diagnosis of 24.7 ± 11.9 years, and average age at infliximab initiation of 34.8 ± 14.8 years. Of the 68 patients, 19% initiated infliximab within 2 years of diagnosis, and 51% had concurrent immunosuppressant therapy at the time of therapy initiation. Fifty percent of patients required dose escalation and the median time from therapy initiation to dose escalation was 10 mo (interquartile range: 5.3-14.8) (Table 1). Four patients discontinued therapy before 12 mo without dose escalation (2 were due to poor response, 1 was concerned with side-effect profile, and 1 had emergency colectomy), and 10 patients were followed up for < 12 mo; these patients were excluded from analysis. Seven patients discontinued therapy between 12 and 24 mo after therapy initiation: four were due to poor or loss of response to therapy (as defined by persistent symptoms based on assessment by a gastroenterologist); one had emergency colectomy secondary to obstruction; one had elective colectomy; and one discontinued due to concerns regarding side effects.

| Variable | All patients (n = 68) |

| Male | 33 (49) |

| Age at diagnosis1 (yr) | 18 (27) |

| < 17 | 43 (64) |

| 17-40 | 6 (9) |

| > 40 | |

| Age at diagnosisa (yr) | 24.7 ± 11.9 |

| Past and current smoking2 | 17 (25) |

| Age at first infliximab infusion (yr) | 34.8 ± 14.8 |

| Disease behavior3 | 29 (44) |

| Non-stricturing, non-penetrating | 12 (18) |

| Stricturing | 12 (18) |

| Penetrating | 13 (20) |

| Penetrating (perianal) | |

| Years between diagnosis and therapy initiation1 | 7.0 (2.0-14.5) |

| Years between diagnosis and therapy initiation1 | 13 (19) |

| < 2 yr | 54 (81) |

| ≥ 2 yr | |

| Concurrent immunosuppressant therapy1 | 34 (51) |

| Concurrent prednisone therapy3 | 8 (12) |

| < 20 mg/d | 10 (15) |

| ≥ 20 mg/d | |

| Dose escalation | 34 (50) |

| Mean time to dose escalation (mo) | 10.0 (5.3-4.8) |

In the multivariate analysis (Table 2), only the variables “years between diagnosis and infliximab initiation” and “concurrent immunosuppressant therapy” were suggestive of possible impact on the probability of dose escalation within 12 mo or on the timing of dose escalation (P = 0.11 and P = 0.09, respectively). The four groups being compared were: “< 2 years between diagnosis and infliximab initiation with concurrent immunosuppressant therapy”; “< 2 years between diagnosis and infliximab initiation without concurrent immunosuppressant therapy”; “≥ 2 years between diagnosis and infliximab initiation with concurrent immunosuppressant therapy”; and “≥ 2 years between diagnosis and infliximab initiation without concurrent immunosuppressant therapy”.

| Variable | n | Requiring dose escalation within 12 mo | Fisher’s exact test P value | Log-rank test P value |

| Sex | 0.58 | 0.91 | ||

| Male | 24 | 41.7% | ||

| Female | 30 | 33.3% | ||

| Age at diagnosis | 1.00 | 0.72 | ||

| < 17 yr | 11 | 36.4% | ||

| 17-40 yr | 36 | 36.1% | ||

| > 40 yr | 6 | 33.3% | ||

| Disease behavior | 0.91 | 1.00 | ||

| Non-stricturing, non-penetrating | 24 | 37.5% | ||

| Stricturing | 9 | 44.4% | ||

| Penetrating | 9 | 33.3% | ||

| Penetrating (perianal) | 11 | 27.3% | ||

| Years between diagnosis and therapy initiation | 0.31 | 0.11 | ||

| < 2 yr | 12 | 50.0% | ||

| ≥ 2 yr | 41 | 31.7% | ||

| Concurrent immunosuppressant therapy | 0.16 | 0.09 | ||

| No | 27 | 48.1% | ||

| Yes | 26 | 26.9% | ||

Fisher’s exact test was conducted on the four groups depending on the time from diagnosis to initiation of infliximab and exposure to immunosuppressants (Table 3). Although there were no significant differences between these groups individually (P = 0.19), the proportion of patients that needed dose escalation within 12 mo was substantially higher for those starting infliximab within 2 years of diagnosis and not on concurrent immunosuppressant therapy than the other three groups combined (P = 0.05). Kaplan-Meier survival curves in Figure 1 showed a similar result (P = 0.01). The median time to dose escalation was 5 mo for those who started infliximab within 2 years of diagnosis and not on concurrent immunosuppressant, and 19 mo for the other three groups combined (Log rank, P < 0.01).

| Years between diagnosis and therapy initiation | < 2 yr | ≥ 2 yr | ||

| On concurrent immunosuppressant therapy | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Proportion of subjects needed dose escalation within 12 mo | 4/5 = 0.80 | 2/7 = 0.29 | 8/21 = 0.38 | 5/19 = 0.26 |

Several associations have been postulated to explain infliximab dose escalation requirements, including development of neutralizing antibodies, augmented clearance, concomitant drug interactions, and genetic factors[20]. Although several studies have shown poor correlation of clinical response and immunogenicity, more recent data suggest that immunosuppression with infliximab increases efficacy, and the pathophysiology likely stems at least in part from a reduction in anti-infliximab antibody formation[14,21]. Several studies have demonstrated that there is a significant benefit in steroid-free remission and mucosal healing in early combination immunosuppression and biologic therapy compared to immunosuppression alone[22-24]. Support for the immunogenicity phenomenon was also observed in this study cohort.

All patients had moderate to severe CD (HBI > 8). Five factors were preselected for analysis: concurrent immunosuppressant therapy; years between diagnosis and infliximab initiation; disease behavior; age at diagnosis; and sex. There was a significantly higher probability of requiring dose escalation in the group of patients in whom therapy was initiated within < 2 years and not on immunosuppressant therapy (P < 0.01) than in the other three groups combined. Trough levels of serum infliximab were not available at our center. Despite the small sample size, these data support the importance of concurrent immunosuppressant therapy while on infliximab as previously described by the SONIC trial[14]. Being a retrospective cohort study, we were not able to collect all the variables necessary to prove our hypothesis, however, our suspicion is that those who required infliximab therapy earlier (< 2 years) than the rest of the cohort had a higher inflammatory burden of disease. If this assumption is true, it would explain why concomitant immunosuppression is so important in this clinical context. This may also suggest that concomitant immunosuppression is not as important when anti-TNF agents are used in scenarios where the inflammatory burden is less. This factor may in part explain the difference in the results from the SONIC study[14] (mean duration of disease for patients on combination therapy: 2.2 years) and the COMMIT study[25] (mean duration of disease for patients on combination therapy: 10.8 years).

Compared to patients diagnosed with CD > 2 years from initiating infliximab, those who receive infliximab within 2 years of diagnosis require more intense immunosuppressant therapy to avoid dose escalation. Further studies are required to determine optimal induction therapy for CD patients with a significant inflammatory burden. A broader question raised by this study is the importance of assessing a patient’s inflammatory burden and how this may influence our choice of therapy.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α is a proinflammatory cytokine that has an important role in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease (CD). Serum and intestinal mucosa TNF-α levels are increased in CD, and disease activity is reduced by TNF-α-blocking agents.

Several studies have shown poor correlation of clinical response and immunogenicity. More recent data suggest that immunosuppression with infliximab increases efficacy, and the pathophysiology likely stems at least in part from the reduction of anti-infliximab antibody formation.

The present study determined the relationship between time fo infliximab initiation from disease diagnosis to the time of infliximab initiation to dose escalation.

There was a significantly higher probability of requiring dose escalation in the group of patients in whom therapy was initiated within < 2 years and not on immunosuppressant therapy than in the other three groups combined.

This is an interesting paper on the association of infliximab with immunosuppressive therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. It could be better divided into the pertinent variables before making conclusions about the note of early vs late introduction of infliximab and the influence of immunogenicity.

P- Reviewers: Bonaz B, Korelitz BI S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: Kerr C E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Fiorino G, Rovida S, Correale C, Malesci A, Danese S. Emerging biologics in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: what is around the corner? Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11:249-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chowers Y, Allez M. Efficacy of anti-TNF in Crohn’s disease: how does it work? Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11:138-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Oussalah A, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Efficacy of TNF antagonists beyond one year in adult and pediatric inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11:156-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Deltenre P, de Suray N, Branche J, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF. Efficacy and safety of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in Crohn’s disease: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:644-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in RCA: 434] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Reimund JM, Wittersheim C, Dumont S, Muller CD, Kenney JS, Baumann R, Poindron P, Duclos B. Increased production of tumour necrosis factor-alpha interleukin-1 beta, and interleukin-6 by morphologically normal intestinal biopsies from patients with Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1996;39:684-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Komatsu M, Kobayashi D, Saito K, Furuya D, Yagihashi A, Araake H, Tsuji N, Sakamaki S, Niitsu Y, Watanabe N. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in serum of patients with inflammatory bowel disease as measured by a highly sensitive immuno-PCR. Clin Chem. 2001;47:1297-1301. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541-1549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2987] [Cited by in RCA: 3055] [Article Influence: 132.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, Chey WY, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Kamm MA, Korzenik JR, Lashner BA, Onken JE. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1581] [Cited by in RCA: 1553] [Article Influence: 74.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, Hanauer SB, Panaccione R, Schreiber S, Byczkowski D, Li J, Kent JD. Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn’s disease: the CHARM trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:52-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1598] [Cited by in RCA: 1620] [Article Influence: 90.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schreiber S, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak RN, Khaliq-Kareemi M, Kamm MA, Boivin M, Bernstein CN, Staun M, Thomsen OØ, Innes A. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of certolizumab pegol (CDP870) for treatment of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:807-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 441] [Cited by in RCA: 424] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, Enns R, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, Lawrance IC, Panaccione R, Sanders M, Schreiber S, Targan S. Natalizumab induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1912-1925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 698] [Cited by in RCA: 664] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Behm BW, Bickston SJ. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha antibody for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;CD006893. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Akobeng AK, Zachos M. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha antibody for induction of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;CD003574. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Rachmilewitz D, Lichtiger S, D’Haens G, Diamond RH, Broussard DL. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1383-1395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2539] [Cited by in RCA: 2375] [Article Influence: 158.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Gisbert JP, Panés J. Loss of response and requirement of infliximab dose intensification in Crohn’s disease: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:760-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 399] [Article Influence: 24.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Regueiro M, Siemanowski B, Kip KE, Plevy S. Infliximab dose intensification in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1093-1099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Travers S, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462-2476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2744] [Cited by in RCA: 2885] [Article Influence: 144.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 18. | Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM. A simple index of Crohn’s-disease activity. Lancet. 1980;1:514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1940] [Cited by in RCA: 2188] [Article Influence: 48.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1970] [Cited by in RCA: 2349] [Article Influence: 123.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 20. | Danese S, Fiorino G, Reinisch W. Review article: Causative factors and the clinical management of patients with Crohn’s disease who lose response to anti-TNF-α therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Maser EA, Villela R, Silverberg MS, Greenberg GR. Association of trough serum infliximab to clinical outcome after scheduled maintenance treatment for Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1248-1254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 483] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | D’Haens G, Baert F, van Assche G, Caenepeel P, Vergauwe P, Tuynman H, De Vos M, van Deventer S, Stitt L, Donner A. Early combined immunosuppression or conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease: an open randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371:660-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 922] [Cited by in RCA: 940] [Article Influence: 55.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lémann M, Mary JY, Duclos B, Veyrac M, Dupas JL, Delchier JC, Laharie D, Moreau J, Cadiot G, Picon L. Infliximab plus azathioprine for steroid-dependent Crohn’s disease patients: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1054-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sandborn WJ. State-of-the-art: Immunosuppression and biologic therapy. Dig Dis. 2010;28:536-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Feagan B, McDonald J, Panaccione R, Enns R. A Randomized Trial of Methotrexate in Combination with Infliximab for the Treatment of Crohn's Disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:294-296. [DOI] [Full Text] |