INTRODUCTION

Nonpathologic lymphangiectasias are commonly detected throughout the gastrointestinal (GI) tract[1]. Lymphangiectasias can be pathologic, thus leading to GI symptoms including abdominal pain, steatorrhea, ascites, and, rarely, mid-gastrointestinal bleeding[2-4]. Small bowel infections such as tuberculosis or parasitic infections that cause impaired lymph flow might lead to diffuse lymphangiectasia resulting in protein-losing enteropathy[5]. Other infectious diseases can also cause focal lymphangiectasia and obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Lymphangiectasia presents either as whitish spots or specks, or yellowish, well-circumscribed, raised mucosal or submucosal lesions on endoscopy[6,7]. The polypoid form is extremely rare in patients with gastrointestinal vascular and lymphatic malformation. A few cases of small bowel bleeding resulting from lymphangiectasia have been reported. In this report, we present a case of ileal lymphangiectasia that was detected and treated by double balloon enteroscopy (DBE).

CASE REPORT

An 80-year-old woman was referred to our department for investigation of gastrointestinal bleeding that she experienced for 7 d. She had chronic kidney disease and atrial fibrillation. She had been receiving hemodialysis twice a week for approximately 1 year prior to this episode, and had been taking warfarin for approximately 2 years. She had no history of habitual drinking or smoking and no specific family history of other diseases. On admission, her blood pressure was 120/80 mmHg, heart rate was 66 bpm, body temperature was 36.1 °C, and respiratory rate was 22 breaths/min. On physical examination, the patient was alert and pale, and digital rectal examination revealed melena. Laboratory studies showed the following values: hemoglobin (Hb), 8.1 g/dL; hematocrit, 23.6%; white blood cells, 11300/μL (neutrophils, 79.1%; lymphocytes, 13.9%; eosinophils, 2.5%); platelets, 209/μL; prothrombin time, 27.3 s (International Normalized Ratio, 2.53); activated partial thromboplastin time; 28.8 s, protein, 8.2 g/dL; albumin, 4.5 g/dL; aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase, 19/11 IU/L; alkaline phosphatase/gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, 64/14 IU/L; total bilirubin, 0.43 mg/dL; and direct bilirubin, 0.15 mg/dL. We stopped warfarin on admission. We measured her Hb level every 4 h and administered packed red blood cell (RBC) transfusion when her Hb level was < 8.0 g/dL. Consequently, she received 4 pints of packed RBC by transfusion during hospitalization. An emergency esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed atrophic mucosal changes and several raised erosions in the antrum; however, no active bleeding was found. A subsequent colonoscopy showed fresh bloody material gushing from the small bowel (Figure 1A-C). An abdominal-pelvic contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan did not reveal any abnormal findings. Video capsule endoscopy (IntroMedic, Seoul, South Korea) showed evidence of active and recent bleeding in the ileum but could not localize the bleeding site (Figure 1D). To localize the bleeding site, we performed DBE. Retrograde DBE (EN450T5, Fujinon, Saitama, Japan) showed a small bleeding polyp in the distal ileum (Figure 2A). The ileal polyp was removed using an endoscopic snare (SD-9L-1; Olympus Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Thereafter, electrocautery was performed after submucosal injection of a hypertonic saline-epinephrine solution (Figure 2B and C). After the procedure, argon plasma coagulation was performed for an ulcer caused by polypectomy to attain hemostasis (Figure 2D). The entire procedure lasted for approximately 150 min. The results of the histological examination were consistent with a diagnosis of lymphangiectasia characterized by dilated lymphatic channels in the lamina propria (Figure 3). We administered warfarin 3 d after the procedure. After removal of the ileal polyp, the patient was discharged with no gastrointestinal bleeding. The patient has been followed up for 1 year and has shown no sign of recurrence.

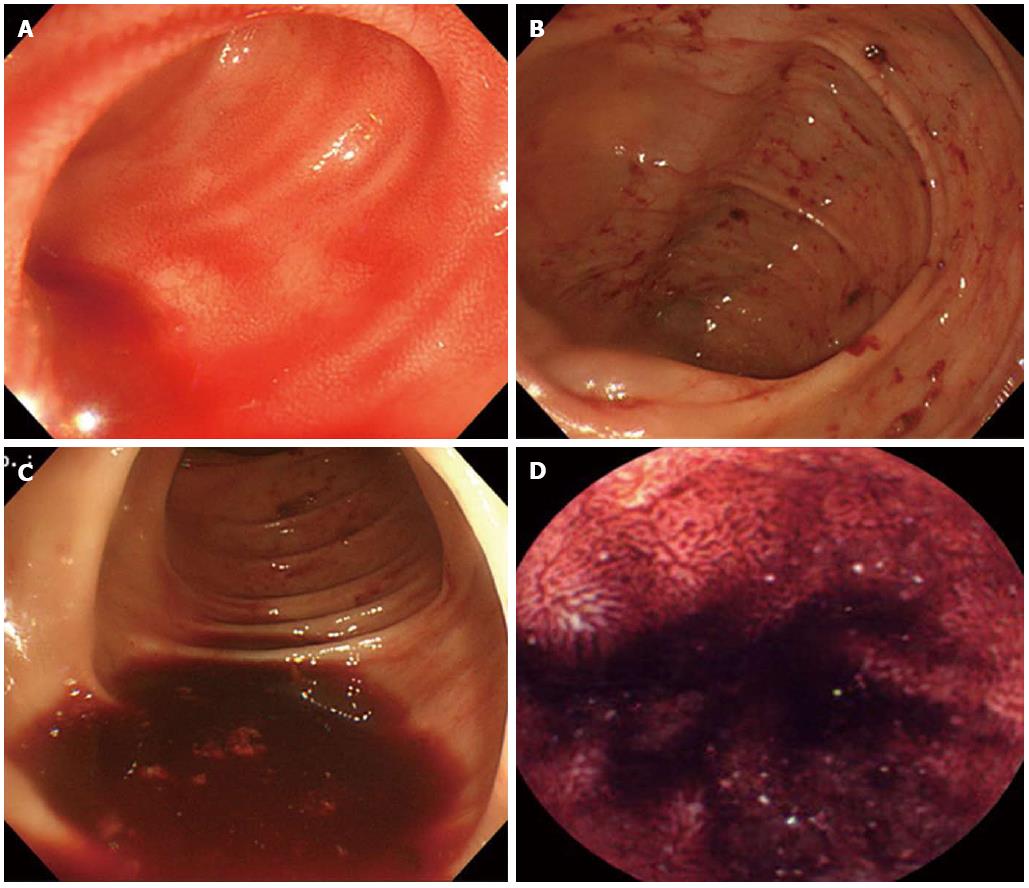

Figure 1 Colonoscopy and video capsule endoscopy findings.

A-C: Colonoscopy shows fresh blood material that gushed from the small bowel; D: Subsequent video capsule endoscopy shows evidence of active and recent bleeding in the ileum.

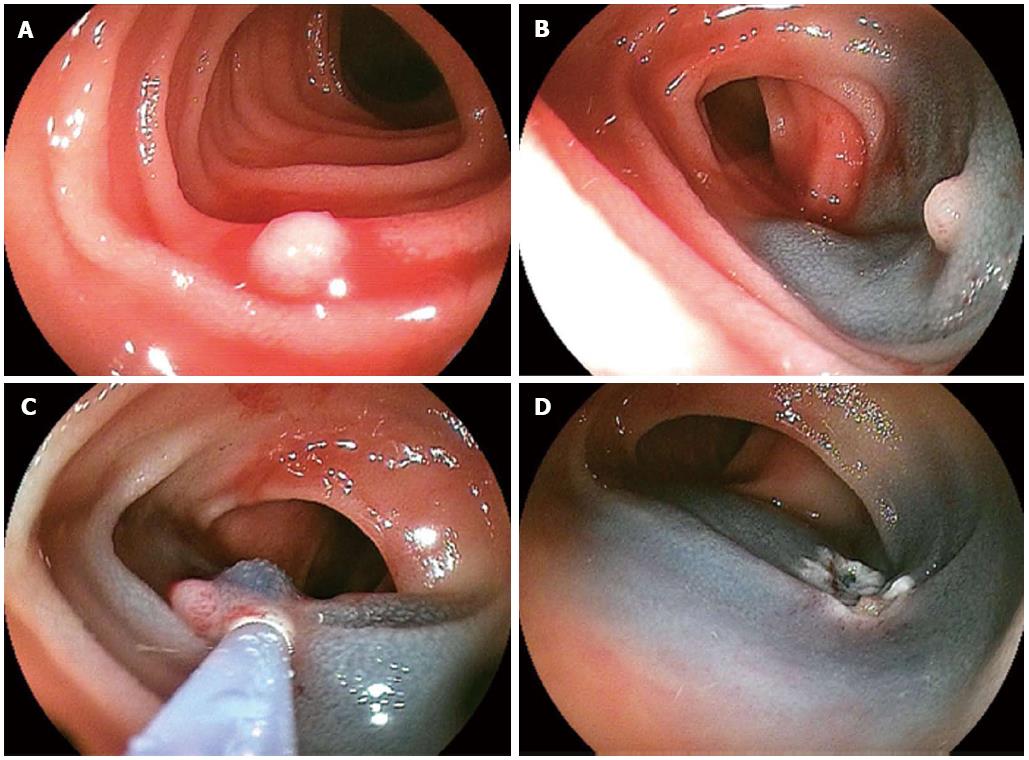

Figure 2 Double balloon enteroscopy findings.

A: Double balloon enteroscopy shows a small, whitish polypoid lesion with active bleeding in the distal ileum; B, C: After submucosal injection of a saline-epinephrine mixture, polypectomy was performed; D: After the procedure, argon plasma coagulation was performed on the post-polypectomy ulcer to achieve hemostasis.

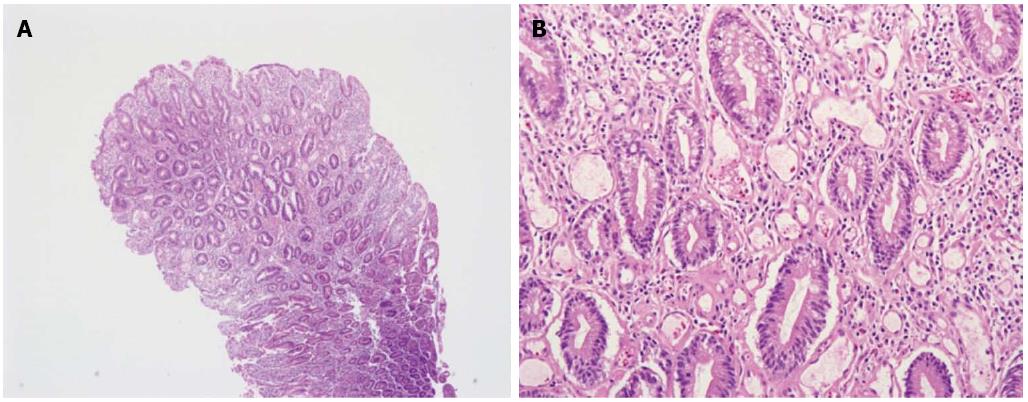

Figure 3 Histopathologic findings of intestinal lymphangiectasia.

A, B: Microscopic examination shows dilated lymphatic channels in the lamina propria (hematoxylin and eosin, × 40). Protein-rich fluid can escape from these channels into the extracellular space of the lamina propria and ultimately into the gut lumen (hematoxylin and eosin, × 200).

DISCUSSION

Intestinal lymphangiectasia is a rare disease characterized by dilated intestinal lacteals causing loss of lymph into the lumen of the small intestine resulting in hypoproteinemia, hypogammaglobulinemia, hypoalbuminemia, and lymphopenia[8]. The most commonly affected site in the intestine is the duodenum[9,10].

Gastrointestinal symptoms range from mild to severe presentations such as diarrhea, steatorrhea, abdominal mass, and mechanical ileus. Chronic occult blood loss may occur in some cases, and non-specific small bowel ulceration has been reported in others[9,11,12]. Rarely, massive bleeding has also been recorded[13,14]. The patient in our case had chronic kidney disease and was receiving treatment with warfarin for atrial fibrillation. Although we could not find any report on whether anticoagulation or hemodialysis increased the risk of bleeding in patients with lymphangiectasia, we consider that she had a bleeding diathesis and hence, had bleeding from the ileal polyp.

Several mechanisms have been suggested to interpret the pathophysiology of bleeding lymphangiectasias. Obstruction of the normal flow of chyle from the small intestine may increase intraluminal pressure sufficiently to open latent lymphatic-venous connections[15]. Consequently, this pressure gradient opens latent lymphatic-arterial (rather than venous) connections[16]. Such openings into another closed system of higher pressure would allow the retrograde flow of blood into the lymphatics and as a result, bursting of blood-filled dilated lymphatics may lead to intestinal bleeding. However, we could find neither the pathologic lymphatic-blood vessel connection nor obstruction of lymphatic channel in the pathological sections of the biopsy specimen.

Intestinal lymphangiectasia was confirmed by the endoscopic findings and intestinal biopsy results. Marked dilation of the lymphatics was seen in the mucosa, sometimes extending into the submucosa. The overlying intestinal epithelium usually appears normal, but occasionally creamy yellow villi may be seen[17]. In recent years, the development of newer endoscopic methods, particularly video capsule endoscopy and DBE has simplified diagnosis and treatment of small bowel lesions. In our case, although small bowel bleeding was detected by video capsule endoscopy, the definite location and etiology of bleeding could not be confirmed. As the bleeding lesion was found to be limited to the ileum in video capsule endoscopy, DBE was performed by the anal approach. The oral approach was not used subsequently because there were no signs of bleeding after polypectomy and coagulation. We diagnosed and treated ileal polypoid intestinal lymphangiectasia using DBE.

To our knowledge, this is the first case to report small bowel bleeding from a solitary ileal polypoid intestinal lymphangiectasia. This case represents the successful detection and treatment of bleeding resulting from rare, solitary, ileal polypoid intestinal lymphangiectasia using DBE.

P- Reviewers: Ciaccio EJ, Oka S, Shah JA, Ye BD S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: Cant MR E- Editor: Zhang DN