Published online Nov 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i44.8151

Revised: September 27, 2013

Accepted: October 13, 2013

Published online: November 28, 2013

Processing time: 116 Days and 2 Hours

Paragangliomas typically develop in the extra-adrenal sites along the sympathetic and/or the parasympathetic chain. Occasionally, the tumors may arise in some exotic sites, including the head and neck region and the urogenital tract. Paraganglioma presenting as a primary rectal neoplasm has not been well described in the literature. Here, we report the first case of malignant paraganglioma arising in the rectum of a 37-year-old male. He presented to the clinic because of hematochezia with tenesmus. The anorectal digital examination and colonoscopic examination revealed a polypoid mass of the rectum, measuring approximately 4 cm in diameter. The overall morphology and immunophenotype were consistent with a typical paraganglioma. However, the tumor exhibited features suggestive of malignant potential, including local extension into adjacent adipose tissue, nuclear pleomorphism, confluent tumor necrosis, vascular invasion and metastases to regional lymph nodes. In conclusion, we present the first case of rectal malignant paraganglioma. Due to the unexpected occurrence in this region, malignant paraganglioma may be misdiagnosed as other tumors with overlapping features; in particular, a neuroendocrine tumor of epithelial origin. Because of the differences in treatment, separating paraganglioma from its mimics is imperative. Combination of morphology with judicious immunohistochemical study is helpful in obtaining the correct diagnosis.

Core tip: We report a rare case of malignant paraganglioma arising in the rectum of a 37-year-old male. To the best of our knowledge, the current case represents the first case of malignant paraganglioma arising in the rectum. Due to the unexpected occurrence in this region, rectal paraganglioma may be misdiagnosed as other common types of tumors with overlapping features; in particular, a neuroendocrine tumor of epithelial origin. Because of the differences in treatment, separating paraganglioma from its mimics is imperative.

- Citation: Yu L, Wang J. Malignant paraganglioma of the rectum: The first case report and a review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(44): 8151-8155

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i44/8151.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i44.8151

Paragangliomas are rare but well-described non-epithelial neuroendocrine tumors that typically develop in the extra-adrenal sites along the sympathetic and/or the parasympathetic chain[1]. Occasionally, the tumors may arise in some exotic sites where normal paraganglia are not well documented. The majority of these unusual tumors have been described preferentially in the head and neck region and the urogenital tract[2]. With the exception of gangliocytic paraganglioma, paraganglioma is extremely rare in the gastrointestinal tract. Of note, the hitherto reported gastrointestinal paragangliomas are exclusively limited to the stomach[3-7]. To the best of our knowledge, paraganglioma has not been well described in the rectum. Due to the unexpected occurrence in this region, rectal paraganglioma may be misdiagnosed as other common types of rectal tumors with morphological overlap. Because the treatments vary, separation of rectal paraganglioma from its mimics, in particular neuroendocrine tumors of epithelial origin, is imperative. In this study, we report a case of malignant paraganglioma presenting as a primary rectal neoplasm to broaden the clinical and morphological spectrum.

A 37-year-old male presented to the clinic because of hematochezia. The symptom had lasted for 8 mo and was accompanied intermittently with tenesmus. On anorectal digital examination, a round firm mass was identified on the posterior wall of the rectum. Colonoscopic examination revealed a polypoid mass, measuring approximately 4 cm in diameter. Clinically, the mass was suspected to be a rectal carcinoma. A biopsy was performed and was interpreted as a low-grade neuroendocrine tumor. After the admission, laparoscopic radical rectectomy was performed. The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient received no adjunctive therapy after surgery and is well at 9-mo follow-up.

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections were reviewed. Immunohistochemical study was performed on 4-mm thick unstained sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue using the standard EnVision technique. The primary antibodies used in the study included antibodies against Chromogranin A (dilution 1:200), synaptophysin (dilution 1:100), neuron-specific enolase (dilution 1:100), CD56 (dilution 1:50), S100 protein (dilution 1:300), pancytokeratin (dilution 1:100), cytokeratin 8/18 (dilution 1:50), epithelial membrane antigen (dilution 1:200), CD34 (dilution 1:50), Human Melanoma Black 45 (dilution 1:60), alpha smooth muscle actin (dilution 1:400), desmin (dilution 1:500), CD117 (dilution 1:100), and discovered on GIST-1 (DOG1) (dilution 1:100). Heat-induced epitope retrieval was performed using a pressure cooker. Appropriate positive controls were run simultaneously throughout the process.

The resected specimen consisted of a segment of rectum measuring 11 cm in length. A polypoid mass was observed protruding into the intestinal cavity, measuring 4.0 cm × 4.0 cm × 1.5 cm in size. On the cut section, the tumor was red-brownish in color and fleshy in consistency, involving the full thickness of the intestinal wall with local extension into the adjacent adipose tissue.

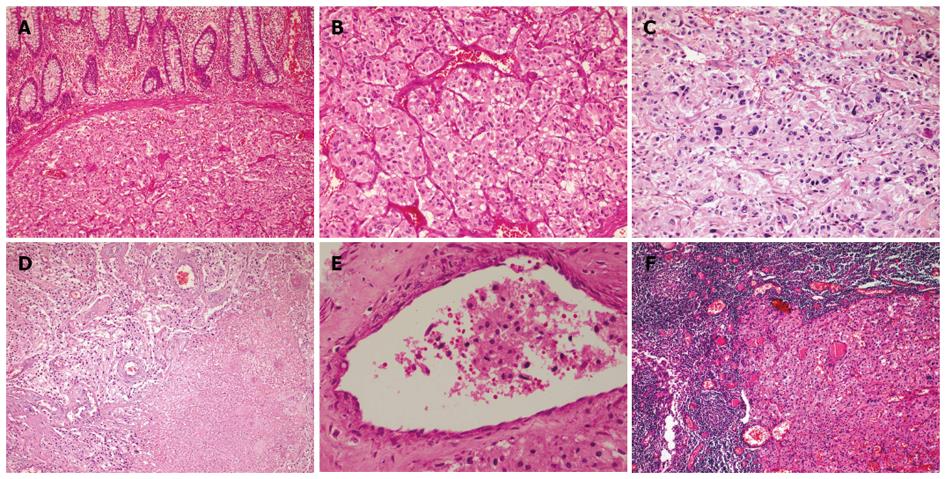

Histologically, the tumor was composed of sheets or organoid nests of large polygonal cells surrounded by a rich network of delicate arborizing vasculature, generating a characteristic “zellballen” (Figure 1A and B). The polygonal cells contained copious eosinophilic to amphiphilic granular cytoplasm, with round to oval nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Although focal nuclear pleomorphism was present (Figure 1C), mitotic activity was relatively low (1-2/50 high power fields). Confluent tumor necrosis and vascular invasion were observed (Figure 1D and E). In addition, the tumor cells metastasized to regional lymph nodes (Figure 1F).

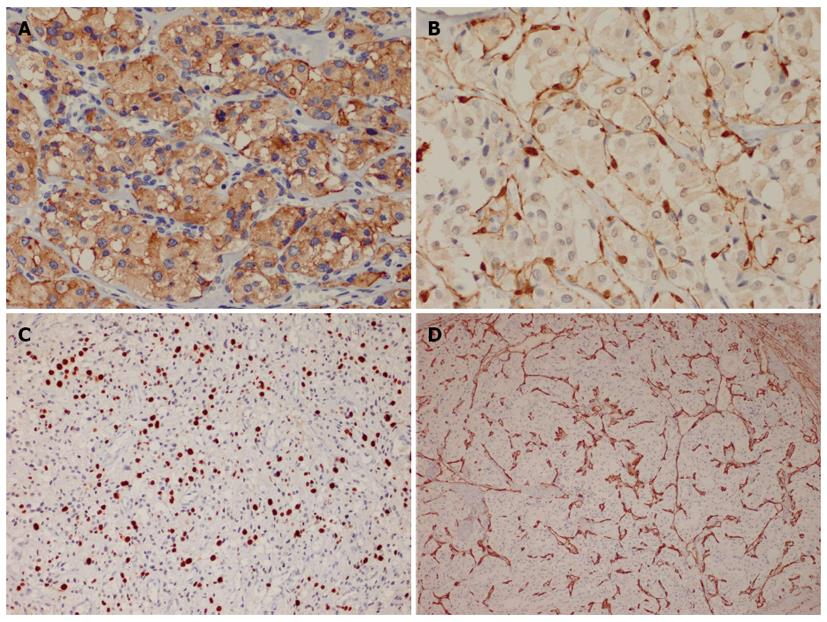

Immunohistochemically, the large polygonal cells exhibited diffuse and strong expression of chromogranin A (Figure 2A), synaptophysin, CD56, neuron-specific enolase and vimentin. In areas with distinct organoid structure, the staining of S100 protein highlighted the presence of slender sustentacular cells located at the periphery of the tumor nests (Figure 2B). However, in areas with more diffuse architecture, the sustentacular cells were difficult to identify. The tumor cells were negative for all of the epithelial, melanocytic, myogenic and Cajal cell markers tested in this study. The Ki67 index was approximately 20% (Figure 2C). The endothelial markers of CD34 and CD31 outlined the rich vascular network (Figure 2D).

Paragangliomas have been rarely reported in the gastrointestinal tract. Approximately 12 tumors have been described in this region, most of which were located in the stomach, with only one tumor occurring in the rectum[3-8]. Of note, the only reported rectal paraganglioma was included in a study focusing on a statistical analysis and was only quoted as an anatomic location. Insufficient data were provided in that case, either clinically or pathologically.

In the current study, we present the clinical and pathological features of a malignant paraganglioma occurring in a 37-year-old male who presented with non-specific symptoms. Clinically, the lesion was suspected as a rectal carcinoma based on anorectal digital findings and rectoscopical examination. Due to the striking organoid structure and strong positivity for neuroendocrine markers, the biopsy specimen was initially interpreted as a low-grade neuroendocrine tumor of epithelial origin, formerly known as a carcinoid tumor. The final diagnosis of paraganglioma was established on the postoperative specimen, which provided enough sections for comprehensive review. The negativity for epithelial marker and presence of slender sustentacular cells allowed the distinction from an epithelial neuroendocrine neoplasm. Other tumors that may enter into the differential diagnosis include neoplasms with perivascular epithelioid cell differentiation (PEComas), alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS) and, rarely, gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) of epithelioid subtype. Like paragangliomas, both PEComas and ASPS may exhibit an organoid or nesting pattern surrounded by thin-walled vessels. By immunohistochemistry, PEComas typically express melanocytic and sometimes express myogenic markers, whereas ASPS is characterized by nuclear staining of TFE3 with no expression of neuroendocrine antibodies. The application of Cajal cell markers, namely CD117 and DOG1, will facilitate the distinction from an epithelioid GIST.

Malignant paraganglioma accounts for 14%-50% of all paragangliomas in some large series[9,10]. Only three cases of primary malignant paraganglioma have been reported in the gastrointestinal tract, all of which occurred in the stomach[4-6]. To the best of our knowledge, rectal malignant paraganglioma has not been described thus far. The current case represents the first case of malignant paraganglioma arising in the rectum.

The diagnosis of malignancy in a paraganglioma is based principally on the aggressive behavior of the tumor. According to the World Health Organization classification of tumors of the endocrine system, the reliable diagnostic criteria of malignant paraganglioma refer to the presence of metastasis or tumor spread in sites normally devoid of chromaffin tissue[11]. Although not considered definitive, several morphological features are believed to be correlated with malignant potential. These features include large size of the tumor (> 5 cm), prominent nuclear pleomorphism, increased mitotic activity, presence of confluent tumor necrosis, diffuse growth pattern with a lack of sustentacular cells, extension to adjacent tissues or structures, vascular invasion and high Ki67 index[11,12]. It is worth noting that none of these features are able to identify a malignant tumor alone. As an alternative approach, some scoring systems have been proposed in the evaluation of malignant potential. One of the most utilized scoring systems is the “Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scales Score (PASS)”[13]. A PASS score > 6 is highly suggestive of potential aggressive biological behavior. The current case exhibited local extension into the adjacent adipose tissue, focal nuclear atypia, confluent tumor necrosis, vascular invasion, high Ki67 index and metastases to regional lymph nodes, justifying a diagnosis of malignant paraganglioma.

Recently, an increasing number of studies have focused on identifying molecular markers or biomarkers that can reliably predict malignant potential of the paraganglioma. Several markers, including telomerase, telomerase associated protein, heat shock protein 90, SNAIL and miR-483-5p, also have been found to be closely related to the malignant potential of paraganglioma[10,14]. On the other hand, molecular genetic detection is only gradually being applied to paraganglioma. It has been demonstrated that malignant paraganglioma is strongly associated with SDHB mutations[15]. Despite these recent advances, it remains difficult to reliably predict the outcome of any given patient.

With regard to the prognosis, the 5-year survival rate in malignant paraganglioma is approximately 30%-50%[10]. The majority metastasize to regional lymph nodes, followed by bone, liver and lung[11,14]. At present, there is no optimal therapy for malignant paraganglioma. For the past few years, molecular targeted therapy has been increasingly applied in the therapeutic protocol of malignant paraganglioma. Some targeted agents, such as hypoxia inducible factor-1 a inhibitors, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors (everolimus), and receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (sunitinib), have been attempted with promising effectiveness[14]. Nevertheless, more clinical trials are needed. The patient in the current study received no adjunctive chemotherapy or radiotherapy. He remains well 9 mo after the surgery and continues to be closely monitored.

In summary, we present the first case of rectal malignant paraganglioma. Because of its rarity in the rectum, malignant paraganglioma may be misdiagnosed as other tumors with overlapping features. Because of the differences in treatment, separation of malignant paraganglioma from its mimics, in particular from neuroendocrine carcinoma, is imperative. Combination of morphology with judicious immunohistochemical study is helpful in obtaining the correct diagnosis.

P- Reviewers: Khattab MA, Romani A, Weekitt K S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Logan S E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Grossman AB, Kaltsas GA. Adrenal medulla and pathology. Comprehensive Clinical Endocrinology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Science 2002; 223–237. |

| 2. | Ernest EL. AFIP Atlas of Tumour Patholgy, Series 4. Tumours of the Adrenal Glands and Extraadrenal Paraganglia. Washington, DC: ARP Press 2007; 288–289. |

| 3. | Laforga JB, Vaquero M, Juanpere N. Paragastric paraganglioma: a case report with unusual alveolar pattern and myxoid component. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:815-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Westbrook KC, Bridger WM, Williams GD. Malignant nonchromaffin paraganglioma of the stomach. Am J Surg. 1972;124:407-409. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Schmid C, Beham A, Steindorfer P, Auböck L, Waltner F. Non-functional malignant paraganglioma of the stomach. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1990;417:261-266. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Tsygan VM, Khonelidze GB, Modonova NM, Zisman IF. Malignant paraganglioma of the stomach (one case). Vopr Onkol. 1969;15:75-77. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Crosbie J, Humphreys WG, Maxwell M, Maxwell P, Cameron CH, Toner PG. Gastric paraganglioma: an immunohistological and ultrastructural case study. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol. 1990;22:401-408. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Feng N, Zhang WY, Wu XT. Clinicopathological analysis of paraganglioma with literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3003-3008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chetrit M, Dubé P, Royal V, Leblanc G, Sideris L. Malignant paraganglioma of the mesentery: a case report and review of literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Parenti G, Zampetti B, Rapizzi E, Ercolino T, Giachè V, Mannelli M. Updated and new perspectives on diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy of malignant pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma. J Oncol. 2012;2012:872713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Delellis RA, Lioyd RV, Heitz PH, Eng C. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Endocrine Organs. Lyon: IARCP Press 2004; 147–150. |

| 12. | Kimura N, Watanabe T, Noshiro T, Shizawa S, Miura Y. Histological grading of adrenal and extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas and relationship to prognosis: a clinicopathological analysis of 116 adrenal pheochromocytomas and 30 extra-adrenal sympathetic paragangliomas including 38 malignant tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2005;16:23-32. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Strong VE, Kennedy T, Al-Ahmadie H, Tang L, Coleman J, Fong Y, Brennan M, Ghossein RA. Prognostic indicators of malignancy in adrenal pheochromocytomas: clinical, histopathologic, and cell cycle/apoptosis gene expression analysis. Surgery. 2008;143:759-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chrisoulidou A, Kaltsas G, Ilias I, Grossman AB. The diagnosis and management of malignant phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2007;14:569-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | King KS, Prodanov T, Kantorovich V, Fojo T, Hewitt JK, Zacharin M, Wesley R, Lodish M, Raygada M, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. Metastatic pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma related to primary tumor development in childhood or adolescence: significant link to SDHB mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4137-4142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |