Published online Jan 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i4.561

Revised: December 15, 2012

Accepted: January 5, 2013

Published online: January 28, 2013

Processing time: 90 Days and 17.3 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy of reduced cathartic bowel preparation with 2 L polyethylene glycol (PEG)-4000 electrolyte solution and 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets for computed tomographic colonography (CTC).

METHODS: Sixty subjects who gave informed consent were randomly assigned to study group A, study group B or the control group. On the day prior to CTC, subjects in study group A were given 20 mL 40% wt/vol barium sulfate suspension before 3 mealtimes, 60 mL 60% diatrizoate meglumine diluted in 250 mL water after supper, and 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets 1 h before oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution. Subjects in study group B were treated identically to those in study group A, with the exception of bisacodyl which was given 1 h after oral PEG-4000. Subjects in the control group were managed using the same strategy as the subjects in study group A, but without administration of bisacodyl. Residual stool and fluid scores, the attenuation value of residual fluid, and discomfort during bowel preparation in the three groups were analyzed statistically.

RESULTS: The mean scores for residual stool and fluid in study group A were lower than those in study group B, but the differences were not statistically significant. Subjects in study group A showed greater stool and fluid cleansing ability than the subjects in study group B. The mean scores for residual stool and fluid in study groups A and B were lower than those in the control group, and were significantly different. There was no significant difference in the mean attenuation value of residual fluid between study group A, study group B and the control group. The total discomfort index during bowel preparation was 46, 45 and 45 in the three groups, respectively, with no significant difference.

CONCLUSION: Administration of 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets prior to or after oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution enhances stool and fluid cleansing ability, and has no impact on the attenuation value of residual fluid or the discomfort index. The former is an excellent alternative for CTC colorectum cleansing

- Citation: Chen ZY, Shen HS, Luo MY, Duan CJ, Cai WL, Lu HB, Zhang GP, Liu Y, Liang JZ. Pilot study on efficacy of reduced cathartic bowel preparation with polyethylene glycol and bisacodyl. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(4): 561-568

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i4/561.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i4.561

Computed tomographic colonography (CTC) has been shown to be an effective tool for colorectal cancer screening, due to its non-invasiveness and high sensitivity for polyp and neoplasia detection[1-6]. This sensitivity is comparable to that obtained using optical colonoscopy[7,8]. However, this examination still requires bowel cleansing similar to that used prior to optical colonoscopy[9]. The need for thorough colorectal cleansing using cathartics remains a major barrier limiting subject acceptance[10]. Reduced cathartic bowel preparation will increase subject compliance to CTC screening[11-13]. To date, there is no general consensus on reduced cathartic bowel preparation, which combines easy preparation and good acceptance[14-18].

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) electrolyte solution is an isosmotic laxative which does not cause electrolyte imbalance[19]. To date, a little research has been conducted on reduced cathartic bowel preparation with PEG-3350 and 10 mg bisacodyl for CTC; however, there are no studies on reduced cathartic bowel preparation combining PEG-4000 with 10 mg bisacodyl[9,12]. Hence, the purpose of this pilot study was to prospectively evaluate the efficacy of reduced cathartic bowel preparation with 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution and 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets for CTC.

Our randomized, prospective and investigator-blinded study group was composed of 60 subjects (34 men and 26 women; age range 22-76 years, mean age 43.6 years). Indications for participation were as follows: asymptomatic subjects with increased colorectal cancer risk due to family or personal history; subjects with recent onset of alarm symptoms, i.e., positive fecal occult blood test, blood in feces, abdominal pain, alternating bowel, refractory iron-deficient anemia, constipation or diarrhea. Subjects with age younger than 18 years, inflammatory bowel disease, end-stage renal disease, and women of child-bearing age were excluded.

After a subject was enrolled in the study, he or she was assigned either to study group A, study group B or the control group on the basis of random numbers. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board, and informed consent was obtained from each subject.

Subjects were instructed to avoid solid food on the day prior to the colorectal examinations. Subjects in study group A were given 20 mL 40% wt/vol barium sulfate suspension (Qingdao Dongfeng Chemical Co. Ltd., Shandong, China) before 3 mealtimes (breakfast, 7:00; lunch, 12:00; supper, 19:00) to achieve fecal tagging; for fluid tagging, 60 mL 60% diatrizoate meglumine (Hunan Hansen Pharmacy Co. Ltd, Hunan, China) diluted in 250 mL water was taken orally after supper; and then two 5 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets (Shaanxi Chuanlong Pharmacy Co. Ltd, Shaanxi, China) were administered at 19:00; and finally, at 20:00, 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution (Jiangxi Hengkang Pharmacy Co. Ltd, Jiangxi, China; each liter solution consisted of 15 mEq PEG-4000, 125 mEq Na+, 10 mEq K+, 20 mEq HCO3-, 80 mEq SO42-, and 35 mEq CI-) was administered orally with the first dose of 750 mL, and the remainder was divided into five 250 mL aliquots separated by 15 min. Bowel preparation of the subjects in study group B was identical to that in study group A, with the exception of bisacodyl administration at 21:00. Bowel preparation in subjects in the control group was the same as that in study group A, without administration of bisacodyl.

Anisodamine hydrochloride (10 mg) was injected intramuscularly 10 min before helical computed tomography (CT) scanning to allow optimal colonic distention, minimize peristalsis and alleviate spasms. Subjects were placed in the right lateral decubitus position on the CT table and a rectal catheter with a retention cuff was inserted. After inflation of the retention cuff, the cuff was gently pulled back until its proximal end rested on the anal sphincter. To distend the colorectum as fully as possible, subjects were then moved into the supine position and room air was gently insufflated into the colorectum to maximal subject tolerance using an automated delivery (JS-628, Guangzhou Jinjian Co. Ltd, Guangdong, China). The delivery was stopped if the rectal pressure was consistently over 3.5 kPa.

Scanning was performed with a 128-slice CT scanner (Somatom Definition AS 128, Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany) or a 4-slice CT scanner (Aquilion 4, Toshiba Co., Japan) using the following parameters: collimation, 0.625; thickness, 1 mm; pitch, 1.2; electric current, 60 mA; voltage, 120 kV; matrix, 512 × 512; field of view, 3500-4000 mm. Subjects were instructed to hold their breath during data acquisition. A standard CT scout image of the abdomen and pelvis was acquired to assess the degree of colorectal distention, and more room air was insufflated if required. With the scout image, each examination was tailored to encompass the entire colorectum. Scanning was then performed in the prone position, using the same parameters as those in the supine position.

Subjects were invited to complete a questionnaire to describe their discomfort during bowel preparation. Possible discomfort included thirst, hunger, bloating, abdominal pain, sleep disturbance, malaise, nausea, vomiting, cramping, anal discomfort, dizziness and others.

Axial two-dimensional images in the supine position were evaluated. Axial two-dimensional images in the prone position and multiplanar reformation images were also evaluated when necessary. All images were evaluated by two independent experienced readers, who were blind to histories, clinical symptoms and signs, and reduced cathartic regimens in the subjects, in random order on a picture archiving and communication system workstation with regard to residual stool, residual fluid and attenuation value of the residual fluid. If their evaluations differed, the two readers reached a consensus after reviewing and discussing the controversial images with another senior radiologist. The scores from the two readers were averaged to give an overall score for each segment in each subject. The entire colorectum was divided into six anatomic segments: cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon and rectum.

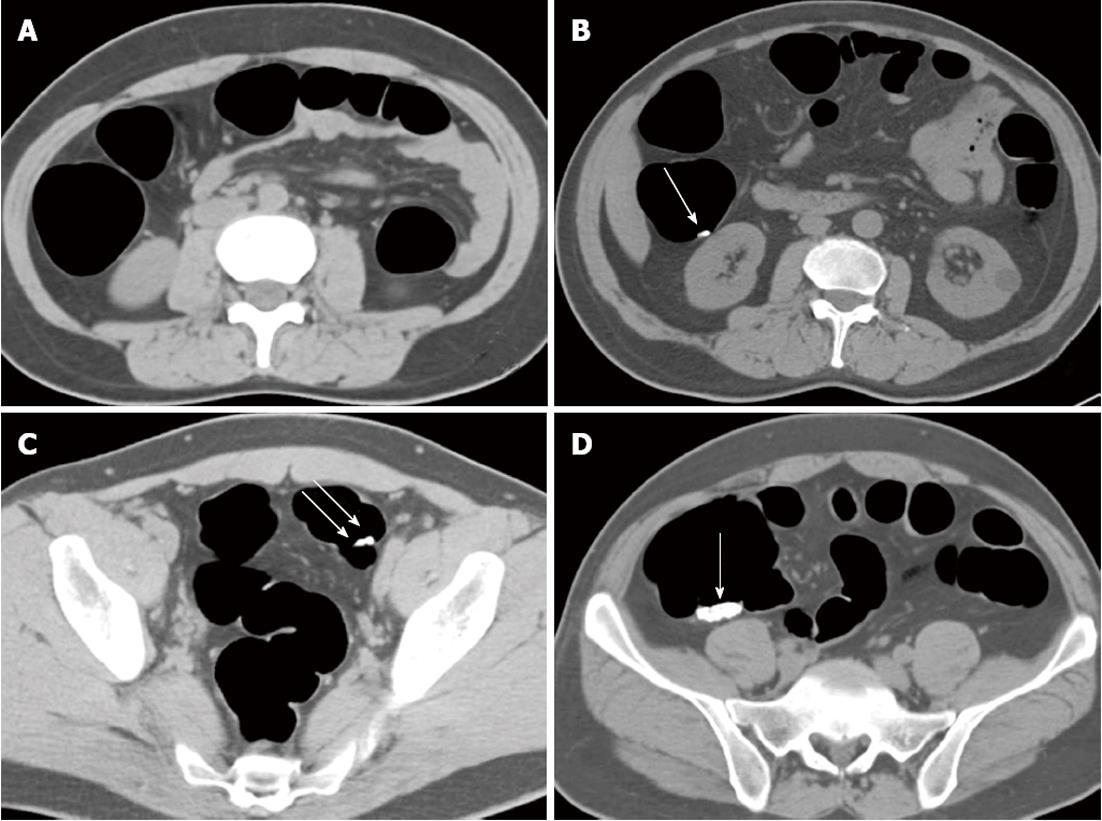

A previously established four-point scoring system was used to evaluate residual stool in each of the six colorectum segments with lower scores corresponding to decreased residual stool[18]. A colorectum segment with no stool was given a score of 1; a segment with a single residual stool particle smaller than 5 mm in diameter, a score of 2; a segment with two or three particles of stool all smaller than 5 mm in diameter, a score of 3; and a segment with stool particles larger than 5 mm or more numerous than three, a score of 4 (Figure 1). A score of 1 or 2, indicated good stool cleansing; and a score of 3 or 4, indicated poor stool cleansing.

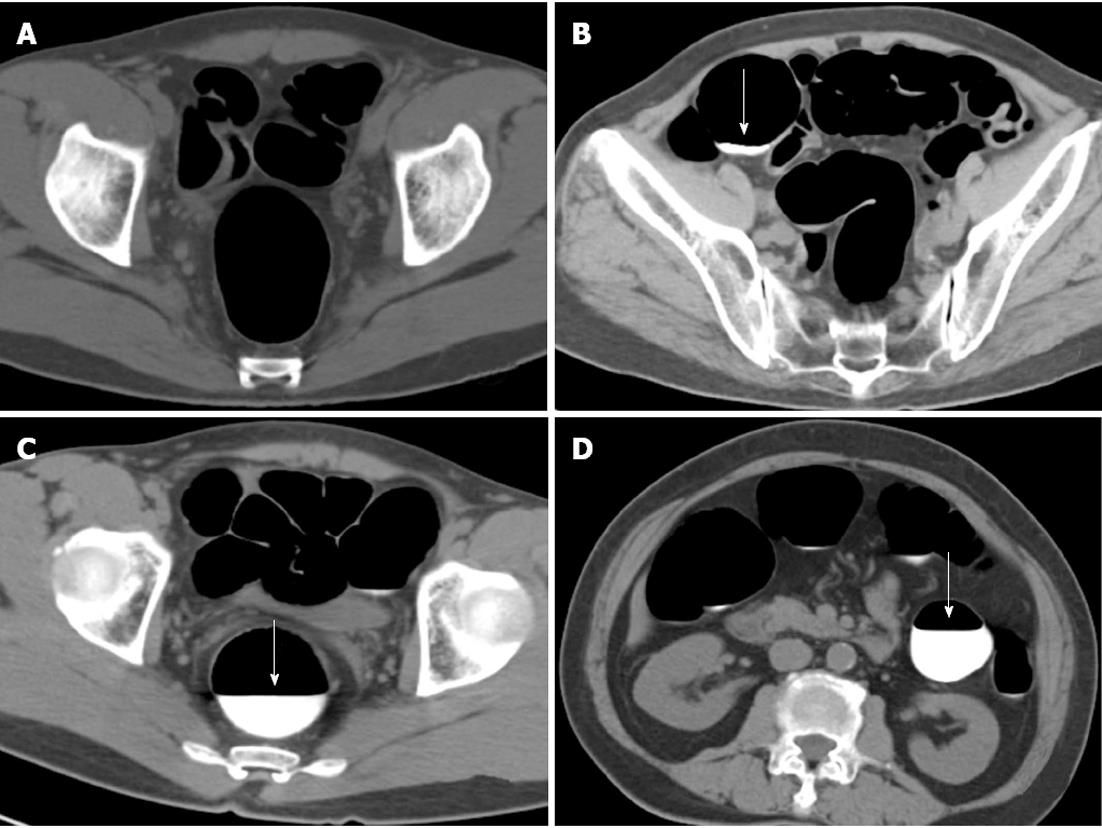

A similar four-point scale was used to assess residual fluid with lower scores corresponding to a decreased percentage of the distended colorectum segment occupied by residual fluid[18]. The score reflected the percentage of the colorectum lumen filled with fluid. A segment with no fluid was given a score of 1; a segment with less than 25% of the lumen filled, a score of 2; a segment with 25%-50% of the lumen filled, a score of 3; and a segment with more than 50% of the lumen filled, a score of 4 (Figure 2). A score of 1 or 2, indicated good fluid cleansing; and a score of 3 or 4, indicated poor fluid cleansing.

The attenuation value of residual fluid was obtained by placing a single region of interest which was approximately 2 cm in diameter in the largest fluid collection. The mean of these measurements was calculated to establish the fluid attenuation value for each fluid collection.

Continuous data were expressed as means with standard deviations unless otherwise specified. Unpaired Student’s t tests with the Welch correction were used to compare residual stool and fluid scores, attenuation value of residual fluid, and discomfort during bowel preparation among the three groups using SPSS version 13.0 for Windows. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In study group A, a residual stool score of 1 was observed in 66 colorectum segments, 2 in 21 colorectum segments, 3 in 5 colorectum segments, 4 in 28 colorectum segments, with a mean score of 1.96 ± 0.11. In study group B, a residual stool score of 1 was observed in 68 colorectum segments, 2 in 15 colorectum segments, 3 in 5 colorectum segments, 4 in 32 colorectum segments, with a mean score of 2.01 ± 0.12. In the control group, a residual stool score of 1 was observed in 37 colorectum segments, 2 in 15 colorectum segments, 3 in 23 colorectum segments, 4 in 45 colorectum segments, with a mean score of 2.63 ± 0.12. There were no significant differences when study group A was compared with study group B (P > 0.05); however, when study group A was compared with the control group (P < 0.001), and study group B was compared with the control group (P < 0.002) significant differences were observed (Table 1).

| Group | Residual stool stool and fluid score | mean ± SD | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Residual stool stool | |||||

| Study group A | 66 (50.0) | 21 (17.5) | 5 (4.2) | 28 (23.3) | 1.96 ± 0.11 |

| Study group B | 68 (56.7) | 15 (12.5) | 5 (4.2) | 32 (26.6) | 2.01 ± 0.12 |

| Control group | 37 (30.8) | 15 (12.5) | 23 (19.2) | 45 (37.5) | 2.63 ± 0.12 |

| Residual fluid score | |||||

| Study group A | 67 (55.9) | 46 (38.3) | 7 (5.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1.50 ± 0.06 |

| Study group B | 66 (55.0) | 45 (37.5) | 8 (6.7) | 1 (0.8) | 1.53 ± 0.06 |

| Control group | 58 (48.4) | 37 (30.8) | 18 (15.0) | 7 (5.8) | 1.78 ± 0.08 |

Good and poor stool cleansing was 72.5% (87/120) and 27.5% (33/120), respectively, in study group A; 69.2% (83/120) and 30.8% (37/120), respectively, in study group B; and 43.3% (52/120) and 56.7% (68/120), respectively, in the control group.

In study group A, a residual fluid score of 1 was observed in 67 colorectum segments, 2 in 46 colorectum segments, 3 in 7 colorectum segments, 4 in 0 colorectum segments, with a mean score of 1.50 ± 0.06. In study group B, a residual fluid score of 1 was observed in 66 colorectum segments, 2 in 45 colorectum segments, 3 in 8 colorectum segments, 4 in 1 colorectum segment, with a mean score of 1.53 ± 0.06. In the control group, a residual fluid score of 1 was observed in 58 colorectum segments, 2 in 37 colorectum segments, 3 in 18 colorectum segments, 4 in 7 colorectum segments, with a mean score of 1.78 ± 0.08. There were no significant differences when study group A was compared with study group B (P > 0.05); however, when study group A was compared with the control group (P < 0.05), and study group B was compared with the control group (P < 0.05) significant differences were observed (Table 1).

Good and poor fluid cleansing was 94.2% (113/120) and 5.8% (7/120), respectively, in study group A; 92.5% (111/120) and 7.5% (9/120), respectively, in study group B; and 79.2% (95/120) and 20.8% (25/120), respectively, in the control group.

In study group A, the attenuation value of residual fluid in the cecum was 718 HU, ascending colon was 840 HU, transverse colon was 704 HU, descending colon was 761 HU, sigmoid colon was 694 HU and rectum was 655 HU, with a mean attenuation value of residual fluid of 729 HU. In study group B, the attenuation value of residual fluid in the cecum was 713 HU, ascending colon was 795 HU, transverse colon was 692 HU, descending colon was 665 HU, sigmoid colon was 532 HU, and rectum was 521 HU, with a mean attenuation value of residual fluid of 653 HU. In the control group, the attenuation value of residual fluid in the cecum was 647 HU, ascending colon was 662 HU, transverse colon was 593 HU, descending colon was 643 HU, sigmoid colon was 534 HU, and rectum was 503 HU, with a mean attenuation value of residual fluid of 597 HU. The P values in study group A, study group B and the control group were all > 0.05 and not statistically significant (Table 2).

| Group | Cecum | Asc c | Tra c | Des c | Sig c | Rectum | Mean |

| Study group A | 718 | 840 | 704 | 761 | 694 | 655 | 729 |

| Study group B | 713 | 795 | 692 | 665 | 532 | 521 | 653 |

| Control group | 647 | 662 | 593 | 643 | 534 | 503 | 597 |

The three most common complaints related to bowel preparation were hunger (n = 43), bloating (n = 37), and thirst (n = 23). Other discomfort experienced during bowel preparation included nausea (n = 10), abdominal pain (n = 9), dizziness (n = 7), sleep disturbance (n = 6), and vomiting (n = 1). There were no serious adverse events during bowel preparation in the three groups. Total discomfort index during bowel preparation in study group A, study group B, and the control group were 46, 45 and 45, respectively, and the differences were not significant (P > 0.05, Table 3).

| Group | Hunger | Bloating | Thirst | Nausea | Abd p | Diz | Sle d | Vom | Total |

| Study group A | 15 | 12 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 46 |

| Study group B | 14 | 13 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 45 |

| Control group | 14 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 45 |

Despite being a preventable neoplasm, colorectal cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in China[20]. Early detection and removal of the precursor lesion significantly reduces the incidence and mortality associated with this neoplasm[21,22]. CTC has been demonstrated to be a feasible and promising new technique in colorectal cancer screening[23-25]. However, with the current methods of CTC, it is necessary to undertake adequate colorectal cleansing to achieve acceptable CTC sensitivity and specificity, as excess stool creates pseudopolyps and obscures true soft-tissue polyp visualization[26,27]. Full bowel preparation with cathartics is the major barrier to screening, due to the discomfort and inconvenience of the associated diarrhea, and negatively affects examination compliance[28]. Reduced cathartic bowel preparation will increase subject compliance, and is under extensive study at present[29-32]. There is no general consensus as to which reduced cathartic bowel preparation to use[33,34]. However, the prospect of replacing conventional preparation with reduced cathartics has driven researchers to identify a new method which combines diagnostic reliability, ease of preparation and subject acceptance[35].

PEG electrolyte solution is an isosmotic laxative which does not cause electrolyte imbalance, and results in improved tagging of residual stool. However, the use of PEG preparations often results in excess residual fluid within the colorectum[19]. As a stimulant laxative, bisacodyl decreases residual fluid. Hence, bowel preparation combining PEG electrolyte solution with bisacodyl enteric-coated tablet may have an ameliorative effect on colorectal cleansing. The standard volume of PEG-3350 is 4 L; each liter of PEG-3350 solution consists of 100 g PEG-3350, 7.5 g sodium sulfate, 2.7 g sodium chloride, 1.0 g potassium chloride, 5.9 g sodium ascorbate, and 4.7 g ascorbic acid. The common dosage of bisacodyl is 20 mg or 10 mg. In our study, a reduced volume of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution and 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets were administered orally; each liter of PEG-4000 electrolyte solution consisted of 15 mEq PEG-4000, 125 mEq Na+, 10 mEq K+, 20 mEq HCO3-, 80 mEq SO42-, and 35 mEq CI-. The molecular weight of PEG-4000 is greater than that of PEG-3350 and has higher viscosity and greater ability to form solids than PEG-3350, and their chemical performance is different.

In our series, the residual stool score in study group A (1.96 ± 0.11) was lower than that in study group B (2.01 ± 0.12) and the difference was not significant, which suggests that the cleansing stool ability was not affected by administration of 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets prior to or after oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution. The residual stool score in study group A (1.96 ± 0.11) was lower than that in the control group (2.63 ± 0.12) and the difference was significant, which suggests that the stool cleansing ability was enhanced by administration of 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets prior to oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution. The residual stool score in study group B (2.01 ± 0.12) was lower than that in the control group (2.63 ± 0.12) and the difference was significant, which suggests that oral administration of 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets after oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution increases stool cleansing ability. Therefore, oral administration of 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets prior to or after oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution improves stool cleansing ability.

Although the residual fluid score in study group A (1.50 ± 0.06) was lower than that in study group B (1.53 ± 0.06) and the difference was not significant, which suggests that the fluid cleansing ability was not influenced by oral administration of 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets prior to or after oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution. The residual stool score in study group A (1.50 ± 0.06) was lower than that in the control group (1.78 ± 0.08) and the difference was significant, which suggests that oral administration of 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets prior to oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution heightened the fluid cleansing ability. The residual fluid score in study group B (1.53 ± 0.06) was lower than that in the control group (1.78 ± 0.08) and the difference was significant, which suggests that the fluid cleansing ability was improved by oral administration of 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets after oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution. Hence, oral administration of 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets prior to or after oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution increases the fluid cleansing ability. Borden et al[18] established a four-point scoring system to evaluate residual fluid in each of the six colorectum segments when comparing magnesium citrate and sodium phosphate. Using the same four-point scoring system, good and poor fluid cleansing was 52% and 48%, respectively, in the study by Hara et al[9] following the ingestion of 10 mg bisacodyl tablets after administration of 4 L PEG-3350. Good and poor fluid cleansing was 92.2% and 7.8%, respectively, in our study after oral administration of 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets 1 h after oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution.

The mean attenuation value of residual fluid in study group A, study group B, and the control group was 729 HU, 653 HU and 597 HU, respectively, with no significant differences. This suggested that oral administration of 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets prior to or after oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution did not affect the mean attenuation value of residual fluid. The attenuation value of residual fluid has been shown to have a significant effect on polyp conspicuity. Previous research has suggested that optimal viewing conditions in the two-dimensional format are met with an attenuation value of residual fluid of approximately 700 HU, due to high conspicuity of all polyps at this level. Such an increase in polyp conspicuity could lead to increased sensitivity and specificity of CTC. With a mean attenuation value of residual fluid of 729 HU, study group A was closer to this optimal level than study group B and the control group.

Total discomfort index during bowel preparation in study group A, study group B, and the control group was 46, 45 and 45, respectively; however, these differences were not significant. There were no serious adverse events during bowel preparation in the three groups. These results suggest that oral administration of 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets prior to or after oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution does not influence subject discomfort during bowel preparation for CTC.

No significant differences were observed between study group A and B with regard to residual stool and fluid scores. However, the residual stool score in study group A (1.96 ± 0.11) was lower than that in study group B (2.01 ± 0.12), and the residual fluid score in study group A (1.50 ± 0.06) was also lower than that in study group B (1.53 ± 0.06), which indicated that oral administration of 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets prior to oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution resulted in a trend toward greater stool and fluid cleansing ability than when given after PEG-4000 electrolyte solution. It would be preferable to administer 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets prior to oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution for CTC bowel preparation.

There were two limitations in our pilot study. First, the number of subjects was relatively small and the study was likely underpowered to detect subtle differences in preparation adequacy. Second, we compared bowel preparation outcomes obtained with these three bowel preparation regimens, but did not assess the possible diagnostic performance of these regimens. Our study was not designed to address diagnostic performance, which will be studied at a later date.

In conclusion, oral administration of 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets prior to or after oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution not only enhances the stool and fluid cleansing ability, but also has no impact on the attenuation value of residual fluid or discomfort during bowel preparation. Oral administration of 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets prior to oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution is an excellent alternative for CTC colorectum cleansing.

Computed tomographic colonography (CTC) has been shown to be an effective tool for colorectal cancer screening. At present, this examination still requires bowel cleansing similar to that used prior to optical colonoscopy. The need for thorough colorectal cleansing using cathartics remains a major barrier limiting subject acceptance. Reduced cathartic bowel preparation will increase subject compliance in CTC screening. There is no general consensus on reduced cathartic bowel preparation.

Reduced cathartic bowel preparation is under extensive study at present. The prospect of replacing conventional preparation with reduced cathartics has driven researchers to identify a new method which combines ease of preparation and subject acceptance.

Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-4000 electrolyte solution is an isosmotic laxative that does not cause electrolyte imbalance, and results in improved tagging of residual stool and excess residual fluid. Bisacodyl enteric-coated tablet, a stimulant laxative, decreases the residual fluid. Bowel preparation with combined PEG-4000 electrolyte solution and bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets has an ameliorative effect on colorectum cleansing.

Oral administration of 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets prior to or after oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution enhances stool and fluid cleansing ability, and has no impact on the attenuation value of residual fluid or discomfort during bowel preparation. Oral administration of 10 mg bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets prior to oral administration of 2 L PEG-4000 electrolyte solution is an excellent alternative for CTC colorectum cleansing.

CTC uses 2D computed tomographic (CT) images of the colorectum, rendered into 3D images and is used to screen for polyps and other abnormalities. The examination consists of non-invasive CT scans, obtained in a few minutes. At the workstation, the images are reconstructed into a 3D model of the colorectum, and the physician may begin clinical analysis of the images.

It is a good reason for physician to find a convenient and effective method for patients to carry bowel preparation. But the cost and benefit and the discomfort score of the patient need to be considered.

P- Reviewers Bhosale PR, Mascalchi M, Lian SL S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Cash BD, Riddle MS, Bhattacharya I, Barlow D, Jensen D, del Pino NM, Pickhardt PJ. CT colonography of a Medicare-aged population: outcomes observed in an analysis of more than 1400 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:W27-W34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pooler BD, Baumel MJ, Cash BD, Moawad FJ, Riddle MS, Patrick AM, Damiano M, Lee MH, Kim DH, Muñoz del Rio A. Screening CT colonography: multicenter survey of patient experience, preference, and potential impact on adherence. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:1361-1366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | de Haan MC, Nio CY, Thomeer M, de Vries AH, Bossuyt PM, Kuipers EJ, Dekker E, Stoker J. Comparing the diagnostic yields of technologists and radiologists in an invitational colorectal cancer screening program performed with CT colonography. Radiology. 2012;264:771-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Laghi A, Iafrate F, Rengo M, Hassan C. Colorectal cancer screening: the role of CT colonography. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3987-3994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Johnson CD, Chen MH, Toledano AY, Heiken JP, Dachman A, Kuo MD, Menias CO, Siewert B, Cheema JI, Obregon RG. Accuracy of CT colonography for detection of large adenomas and cancers. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1207-1217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 848] [Cited by in RCA: 706] [Article Influence: 41.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lieberman DA. Clinical practice. Screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1179-1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ghanouni A, Smith SG, Halligan S, Plumb A, Boone D, Magee MS, Wardle J, von Wagner C. Public perceptions and preferences for CT colonography or colonoscopy in colorectal cancer screening. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89:116-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jensch S, Bipat S, Peringa J, de Vries AH, Heutinck A, Dekker E, Baak LC, Montauban van Swijndregt AD, Stoker J. CT colonography with limited bowel preparation: prospective assessment of patient experience and preference in comparison to optical colonoscopy with cathartic bowel preparation. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:146-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hara AK, Kuo MD, Blevins M, Chen MH, Yee J, Dachman A, Menias CO, Siewert B, Cheema JI, Obregon RG. National CT colonography trial (ACRIN 6664): comparison of three full-laxative bowel preparations in more than 2500 average-risk patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:1076-1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zueco Zueco C, Sobrido Sampedro C, Corroto JD, Rodriguez Fernández P, Fontanillo Fontanillo M. CT colonography without cathartic preparation: positive predictive value and patient experience in clinical practice. Eur Radiol. 2012;22:1195-1204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Johnson CD, Kriegshauser JS, Lund JT, Shiff AD, Wu Q. Partial preparation computed tomographic colonography: a feasibility study. Abdom Imaging. 2011;36:707-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Keedy AW, Yee J, Aslam R, Weinstein S, Landeras LA, Shah JN, McQuaid KR, Yeh BM. Reduced cathartic bowel preparation for CT colonography: prospective comparison of 2-L polyethylene glycol and magnesium citrate. Radiology. 2011;261:156-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liedenbaum MH, Denters MJ, Zijta FM, van Ravesteijn VF, Bipat S, Vos FM, Dekker E, Stoker J. Reducing the oral contrast dose in CT colonography: evaluation of faecal tagging quality and patient acceptance. Clin Radiol. 2011;66:30-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pollentine A, Mortimer A, McCoubrie P, Archer L. Evaluation of two minimal-preparation regimes for CT colonography: optimising image quality and patient acceptability. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:1085-1092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liedenbaum MH, Denters MJ, de Vries AH, van Ravesteijn VF, Bipat S, Vos FM, Dekker E, Stoker J. Low-fiber diet in limited bowel preparation for CT colonography: Influence on image quality and patient acceptance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:W31-W37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Campanella D, Morra L, Delsanto S, Tartaglia V, Asnaghi R, Bert A, Neri E, Regge D. Comparison of three different iodine-based bowel regimens for CT colonography. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:348-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Liedenbaum MH, de Vries AH, Gouw CI, van Rijn AF, Bipat S, Dekker E, Stoker J. CT colonography with minimal bowel preparation: evaluation of tagging quality, patient acceptance and diagnostic accuracy in two iodine-based preparation schemes. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:367-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Borden ZS, Pickhardt PJ, Kim DH, Lubner MG, Agriantonis DJ, Hinshaw JL. Bowel preparation for CT colonography: blinded comparison of magnesium citrate and sodium phosphate for catharsis. Radiology. 2010;254:138-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ell C, Fischbach W, Bronisch HJ, Dertinger S, Layer P, Rünzi M, Schneider T, Kachel G, Grüger J, Köllinger M. Randomized trial of low-volume PEG solution versus standard PEG + electrolytes for bowel cleansing before colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:883-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wu F, Lin GZ, Zhang JX. An overview of cancer incidence and trend in China. Zhongguo Zhongliu. 2012;21:81-85. |

| 21. | Park SH, Yee J, Kim SH, Kim YH. Fundamental elements for successful performance of CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy). Korean J Radiol. 2007;8:264-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lefere PA, Gryspeerdt SS, Dewyspelaere J, Baekelandt M, Van Holsbeeck BG. Dietary fecal tagging as a cleansing method before CT colonography: initial results polyp detection and patient acceptance. Radiology. 2002;224:393-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Heresbach D, Djabbari M, Riou F, Marcus C, Le Sidaner A, Pierredon-Foulogne MA, Ponchon T, Boudiaf M, Seyrig JA, Laumonier H. Accuracy of computed tomographic colonography in a nationwide multicentre trial, and its relation to radiologist expertise. Gut. 2011;60:658-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Howard K, Salkeld G, Pignone M, Hewett P, Cheung P, Olsen J, Clapton W, Roberts-Thomson IC. Preferences for CT colonography and colonoscopy as diagnostic tests for colorectal cancer: a discrete choice experiment. Value Health. 2011;14:1146-1152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Moawad FJ, Maydonovitch CL, Cullen PA, Barlow DS, Jenson DW, Cash BD. CT colonography may improve colorectal cancer screening compliance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:1118-1123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Neri E, Turini F, Cerri F, Vagli P, Bartolozzi C. CT colonography: same-day tagging regimen with iodixanol and reduced cathartic preparation. Abdom Imaging. 2009;34:642-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nagata K, Okawa T, Honma A, Endo S, Kudo SE, Yoshida H. Full-laxative versus minimum-laxative fecal-tagging CT colonography using 64-detector row CT: prospective blinded comparison of diagnostic performance, tagging quality, and patient acceptance. Acad Radiol. 2009;16:780-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yoon SH, Kim SH, Kim SG, Kim SJ, Lee JM, Lee JY, Han JK, Choi BI. Comparison study of different bowel preparation regimens and different fecal-tagging agents on tagging efficacy, patients’ compliance, and diagnostic performance of computed tomographic colonography: preliminary study. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2009;33:657-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Taylor SA, Slater A, Burling DN, Tam E, Greenhalgh R, Gartner L, Scarth J, Pearce R, Bassett P, Halligan S. CT colonography: optimisation, diagnostic performance and patient acceptability of reduced-laxative regimens using barium-based faecal tagging. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:32-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Jensch S, de Vries AH, Peringa J, Bipat S, Dekker E, Baak LC, Bartelsman JF, Heutinck A, Montauban van Swijndregt AD, Stoker J. CT colonography with limited bowel preparation: performance characteristics in an increased-risk population. Radiology. 2008;247:122-132. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Jensch S, de Vries AH, Pot D, Peringa J, Bipat S, Florie J, van Gelder RE, Stoker J. Image quality and patient acceptance of four regimens with different amounts of mild laxatives for CT colonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:158-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Florie J, van Gelder RE, Schutter MP, van Randen A, Venema HW, de Jager S, van der Hulst VP, Prent A, Bipat S, Bossuyt PM. Feasibility study of computed tomography colonography using limited bowel preparation at normal and low-dose levels study. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:3112-3122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Nagata K, Singh AK, Sangwaiya MJ, Näppi J, Zalis ME, Cai W, Yoshida H. Comparative evaluation of the fecal-tagging quality in CT colonography: barium vs. iodinated oral contrast agent. Acad Radiol. 2009;16:1393-1399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kim MJ, Park SH, Lee SS, Byeon JS, Choi EK, Kim JH, Kim YN, Kim AY, Ha HK. Efficacy of barium-based fecal tagging for CT colonography: a comparison between the use of high and low density barium suspensions in a Korean population - a preliminary study. Korean J Radiol. 2009;10:25-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Mahgerefteh S, Fraifeld S, Blachar A, Sosna J. CT colonography with decreased purgation: balancing preparation, performance, and patient acceptance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:1531-1539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |