Published online Jan 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i4.542

Revised: November 7, 2012

Accepted: December 15, 2012

Published online: January 28, 2013

Processing time: 148 Days and 6.7 Hours

AIM: To investigated the incidence of diversion colitis (DC) and impact of DC symptoms on quality of life (QoL) after ileostomy reversal in rectal cancer.

METHODS: We performed a prospective study with 30 patients who underwent low anterior resection and the creation of a temporary ileostomy for the rectal cancer between January 2008 and July 2009 at the Department of Surgery, Korea University Anam Hospital. The participants totally underwent two rounds of the examinations. At first examination, endoscopies, tissue biopsies, and questionnaire survey about the symptom were performed 3-4 mo after the ileostomy creations. At second examination, endoscopies, tissue biopsies, and questionnaire survey about the symptom and QoL were performed 5-6 mo after the ileostomy reversals. Clinicopathological data were based on the histopathological reports and clinical records of the patients.

RESULTS: At the first examination, all of the patients presented with inflammation, which was mild in 15 (50%) patients, moderate in 11 (36.7%) and severe in 4 (13.3%) by endoscopy and mild in 14 (46.7%) and moderate in 16 (53.3%) by histology. At the second examination, only 11 (36.7%) and 17 (56.7%) patients had mild inflammation by endoscopy and histology, respectively. There was no significant difference in DC grade between the endoscopic and the histological findings at first or second examination. The symptoms detected on the first and second questionnaires were mucous discharge in 12 (40%) and 5 (17%) patients, bloody discharge in 5 (17%) and 3 (10%) patients, abdominal pain in 4 (13%) and 2 (7%) patients and tenesmus in 9 (30%) and 5 (17%) patients, respectively. We found no correlation between the endoscopic or histological findings and the symptoms such as mucous discharge, bleeding, abdominal pain and tenesmus in both time points. Diarrhea was detected in 9 patients at the second examination; this number correlated with the severity of DC (0%, 0%, 66.7%, 33.3% vs 0%, 71.4%, 23.8%, 4.8%, P = 0.001) and the symptom-related QoL (r = -0.791, P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION: The severity of DC is related to diarrhea after an ileostomy reversal and may adversely affect QoL.

- Citation: Son DN, Choi DJ, Woo SU, Kim J, Keom BR, Kim CH, Baek SJ, Kim SH. Relationship between diversion colitis and quality of life in rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(4): 542-549

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i4/542.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i4.542

The surgical interruption of fecal flow may induce inflammation in the non-functional region of the distal colon[1]. This condition, diversion colitis (DC), is particularly common after an ileostomy or a colostomy. Theoretically, the inflammation typically resolves when the fecal passage resumes[2]. In Western countries, the estimated incidence of DC ranges from 70% to 100%[1,3], but the incidence in Asian countries is unknown. Glotzer et al[4] first described the clinical symptom related to defunctioned colon. DC symptoms include abdominal pain, bleeding, mucous discharge, and tenesmus; however, many patients do not present with definitive symptoms[5]. Retrospective and prospective studies report abnormal endoscopic and histological findings in most DC patients[3,6-8]. For patients having rectal surgery for cancer, the functional outcome and quality of life (QoL) are related to the length of the remnant rectum, the radiation therapy parameters and the extent of anastomotic leakage[9-11]. After ileostomy reversal, DC may also influence QoL, but the significance of this influence has not been reported. We hypothesized that the endoscopic and histological incidence of DC before and after ileostomy reversal in rectal cancer patients will correspond with patient’s symptoms and impact QoL. Thus, the aims of this study are to determine the incidence of DC and its impact on QoL after ileostomy reversal.

Forty-eight consecutive patients had surgery for rectal cancer and the creation of a temporary ileostomy at our institution between January 2008 and July 2009. Rectal cancer was defined as tumor 16 cm or less from the anal verge measured with a rigid rectosigmoidoscope (lower third, < 6 cm; middle third, 6-12 cm; upper third, 12-16 cm). The eligible patients were aged 18 years or older with, an American Society of Anesthesiologists class 1 to 3 and diagnosed with rectal cancer within 16 cm from the anal verge. The initial exclusion criteria included inflammatory bowel disease, such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, preoperative or postoperative radiation therapy and anastomotic leakage after rectal cancer surgery. The indications for chemoradiation prior to surgery were as follows: T4 lesion involvement below the peritoneal reflection, bulky tumor mass or lateral pelvic lymph node metastasis. The surgical indications for rectal cancer included clinical T1-3 lesions based on a pelvic computed tomography and an magnetic resonance imaging, irrespective of any locally lymph node metastasis the within mesorectal fascia. For the enrolled patients, the stoma closure was performed 3-4 mo after the first surgery to allow for 8 patients with stage III or IV disease to complete intravenous chemotherapy. Each patient was hospitalized on 1 d before the ileostomy reversal. At this time, they underwent the first round of endoscopy, tissue biopsy and completed a questionnaire. A single endoscopist conducted the colonoscopies without an enema to ensure the collection of abnormal tissues. Random biopsies were also performed on the descending or transverse colon, even in case of normal colonoscopic findings. A single pathologist examined the tissues. Both the endoscopist and the pathologist were blinded to the patient’s symptoms. The first DC symptom questionnaire was also performed during these 3 to 4 mo. Five to six months after the ileostomy reversal, the same endoscopist and pathologist conducted endoscopic and histological examinations to evaluate for complete resolution of DC. In the second questionnaire, we investigated symptom changes and related QoL changes. The endoscopic findings were scored according to edema, mucosal hemorrhage and contact bleeding. These features were scored individually from 0 to 3, 0 to 3, and 0 to 1, respectively, for a total score of 0 to 7. The total score was defined as mild (1 to 2), moderate (3 to 5), or severe (6 to 7). The histological findings were scored according to acute inflammation, chronic inflammation, eosinophilic infiltration, crypt architecture distortion, follicular lymphoid hyperplasia and crypt abscess. These features were scored from 0 to 1; 0 to 2; 0 to 2; 0 to 1; 0 to 1; and 0 to 1, respectively, for a total score of 0 to 8. The total score was further defined as mild (1 to 3), moderate (4 to 6), or severe (7 to 8). Both of the questionnaires investigated DC symptoms such as mucous discharge, bleeding, abdominal pain and tenesmus. However, we excluded fecal frequency, incontinence and the symptoms that are associated with intestinal obstruction (abdominal distension and pain, and emesis). We also excluded the bleeding from hemorrhoids and anal fissures. The QoL section of the questionnaire assessed symptomatic changes from before to after ileostomy reversal as follows: “much worse”, “slightly worse”, “similar”, “slightly better”, or “much better”. The institutional review board of our institution approved this study and all of the subjects provided informed consent.

The data were represented as the median (minimum-maximum), as appropriate for quantitative variables and frequency (percentage) for qualitative variables. The χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare between the endoscopic and histological findings about incidence rates of DC, and to test difference or relation with symptoms according to severity of DC and QoL. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The calculations were performed using SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, United States).

Between January 2008 and July 2009, 48 patients were enrolled in the study. However, preceding the study, 18 patients were excluded from the analysis because they underwent a bowel enema procedure (7 patients) that could alter mucosal findings or symptoms, had excessive bowel content that hindered a clear colonoscopic view (9 patients), or had an anastomotic stricture observed during colonoscopy that prevented the visualization of the proximal portion of the colon (2 patients). The final prospective analysis included 30 patients.

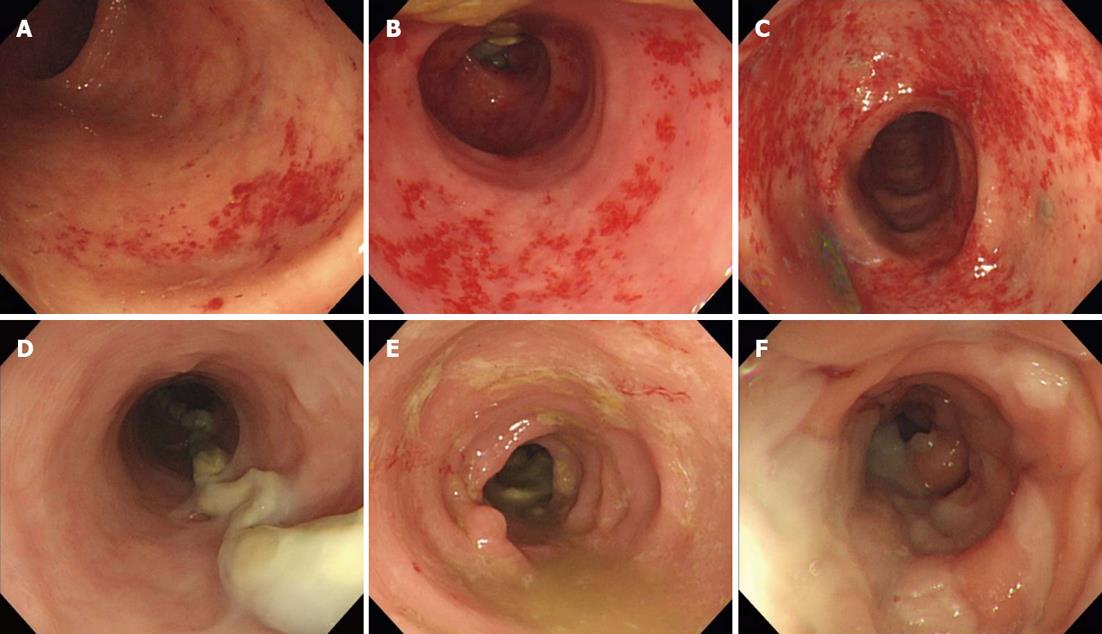

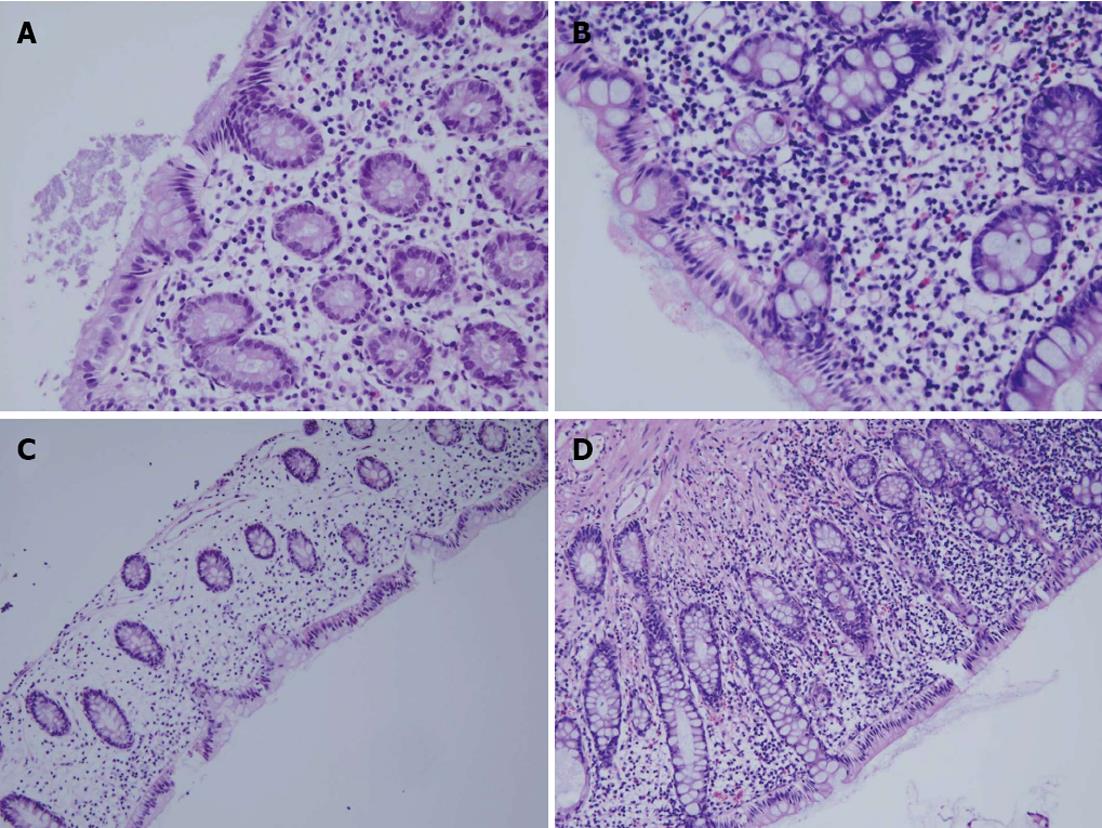

The patients’ characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median age was 59 years (range: 31-73 years) and the male: female ratio was 7:3. The tumor was located in the upper rectum for 6 patients (20%), the mid-rectum for 5 patients (16.7%) and the lower rectum for 19 patients (63.3%). Only 8 patients received intravenous chemotherapy. Using the endoscopic and histological criteria, all of the patients (100%) developed DC after their ileostomy creation (Table 2). There was no significant difference between the endoscopic and the histological findings in terms of the DC grade prior to ileostomy reversal (P = 0.084) or 5-6 mo after reversal (P = 0.195), and the endoscopic and histological features decreased after the ileostomy reversal. The incidence of symptomatic DC was 63.3% after ileostomy creation, and 46.6% 5-6 mo after ileostomy reversal. Figure 1 shows the endoscopic findings by the mucosal hemorrhage and edema severity. Figure 2 shows histological findings by the eosinophilic infiltration and chronic inflammation severity. Of the endoscopic findings, edema and mucosal hemorrhage were most common, and contact bleeding was rare. The most common histological finding was chronic inflammation (100%), followed by eosinophilic infiltration (Table 3). The endoscopic and histological abnormalities disappeared or decreased after the ileostomy reversal (Table 3). Before the ileostomy reversal, the most frequent initial symptom, according to the questionnaires, was mucous discharge, followed by tenesmus, bleeding and abdominal pain (Table 4). There were no reports of anal defecation caused by an ileostomy with incomplete diversion prior to the ileostomy reversal. The answers to the questionnaire conducted 5-6 mo after the ileostomy reversal showed that the symptoms had generally decreased since the first survey (Table 4). However, nine patients developed diarrhea as a new symptom (Table 4). We found no correlation between the endoscopic or histological findings and the symptoms before ileostomy reversal.

| Parameter | Patients |

| Age (yr) | 59 (31-73)1 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 21 (70.0) |

| Female | 9 (30.0) |

| ASA | |

| I | 11 (36.7) |

| II | 15 (50) |

| III | 4 (13.3) |

| IV | 0 |

| Tumor location | |

| Upper rectum | 6 (20.0) |

| Mid rectum | 5 (16.7) |

| Lower rectum | 19 (63.3) |

| Intravenous chemotherapy | |

| No | 22 (73.3) |

| Yes | 8 (26.7) |

| pTNM staging | |

| 0 | 4 (13.3) |

| I | 6 (20.0) |

| II | 11 (36.7) |

| III | 7 (23.3) |

| IV | 2 (6.7) |

| Grade of DC | 1 d prior to ileostomy reversal | 5-6 mo after ileostomy reversal | ||||

| Endoscopic (n = 30) | Histological (n = 30) | P value | Endoscopic (n = 30) | Histological (n = 30) | P value | |

| None | 0 | 0 | 0.084 | 19 (63.3) | 13 (43.3) | 0.195 |

| Mild | 15 (50.0) | 14 (46.7) | 11 (36.7) | 17 (56.7) | ||

| Moderate | 11 (36.7) | 16 (53.3) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Severe | 4 (13.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 d prior to ileostomy reversal (n = 30) | 5-6 mo after ileostomy reversal (n = 30) | |

| Endoscopic finding | ||

| Edema | 30 (100) | 9 (30.0) |

| Mucosal hemorrhage | 22 (73.3) | 3 (10.0) |

| Contact bleeding | 6 (20.0) | 0 |

| Histological finding | ||

| Acute inflammation | 7 (23.3) | 0 |

| Chronic inflammation | 30 (100) | 17 (56.7) |

| Eosinophilic infiltration | 29 (96.7) | 9 (30.0) |

| Crypt architecture distorsion | 6 (20.0) | 0 |

| Follicular lymphoid hyperplasia | 12 (40.0) | 0 |

| Crypt abscess | 7 (23.3) | 0 |

| Symptom | Endoscopic finding (n = 30) | Histological finding (n = 30) | ||||||

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | P value | Mild | Moderate | Severe | P value | |

| Symptoms before ileostomy reversal | ||||||||

| Mucous discharge | 0.073 | 0.284 | ||||||

| Yes | 3 (25.0) | 7 (58.3) | 2 (16.7) | 4 (33.3) | 8 (66.7) | 0 | ||

| No | 12 (66.7) | 4 (22.2) | 2 (11.1) | 10 (55.6) | 8 (44.4) | 0 | ||

| Bleeding | 0.338 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Yes | 1 (20.0) | 3 (60.0) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | 0 | ||

| No | 14 (56.0) | 8 (32.0) | 3 (12.0) | 12 (48.0) | 13 (52.0) | 0 | ||

| Abdominal pain | 0.529 | 0.602 | ||||||

| Yes | 1 (25.0) | 2 (50.0) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | 0 | ||

| No | 14 (53.9) | 9 (34.6) | 3 (11.5) | 13 (50.0) | 13 (50.0) | 0 | ||

| Tenesmus | 0.075 | 0.440 | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (22.2) | 6 (66.7) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (33.3) | 6 (66.7) | 0 | ||

| No | 13 (61.9) | 5 (23.8) | 3 (14.3) | 11 (52.4) | 10 (47.6) | 0 | ||

| Symptoms after ileostomy reversal | ||||||||

| Mucous discharge | 0.679 | 0.336 | ||||||

| Yes | 3 (60.0) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80.0) | 0 | ||

| No | 12 (48.0) | 10 (40.0) | 3 (12.0) | 13 (52.0) | 12 (48.0) | 0 | ||

| Bleeding | 0.550 | 0.228 | ||||||

| Yes | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | 0 | ||

| No | 14 (51.9) | 10 (37.0) | 3 (11.1) | 14 (51.9) | 13 (48.1) | 0 | ||

| Abdominal pain | 0.229 | 0.485 | ||||||

| Yes | 1 (50.0) | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 0 | 2 (100) | 0 | ||

| No | 14 (53.8) | 11 (39.3) | 3 (10.7) | 14 (50.0) | 14 (50.0) | 0 | ||

| Tenesmus | 0.844 | 0.336 | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (40.0) | 2 (40.0) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80.0) | 0 | ||

| No | 13 (52.0) | 9 (36.0) | 3 (12.0) | 13 (52.0) | 12 (48.0) | 0 | ||

| Diarrhea | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | 6 (66.7) | 3 (33.3) | 0 | 9 (100) | 0 | ||

| No | 15 (71.4) | 5 (23.8) | 1 (4.8) | 14 (66.7) | 7 (33.3) | 0 | ||

For example, there were mucous discharge (P = 0.073; P = 0.284), bleeding (P = 0.338; P = 1.000), abdominal pain (P = 0.529; P = 0.602), and tenesmus (P = 0.075; P = 0.440) (Table 4). Of the symptoms reported after the ileostomy reversal, only diarrhea correlated with the endoscopic and histological findings before the ileostomy reversal (P = 0.001; Table 4). In the second questionnaires, 4 patients indicated that they felt ‘much worse’, 8 patients felt ‘slightly worse’, 15 patients felt “similar” and 3 patients felt “slightly better” (Table 5). Finally, diarrhea showed a significant effect in the QoL relevance analysis of symptoms (r = -0.791, P < 0.001; Table 5).

| Symptom | Much worse | Slightly worse | Similar | Slightly better | Much better | P value |

| Mucous discharge | 0.137 | |||||

| Yes | 2 (40.0) | 0 | 2 (40.0) | 1 (20.0) | 0 | |

| No | 2 (8.0) | 8 (32.0) | 13 (52.0) | 2 (8.0) | 0 | |

| Bleeding | 0.797 | |||||

| Yes | 0 | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 0 | 0 | |

| No | 4 (14.8) | 7 (25.9) | 13 (48.1) | 3 (11.1) | 0 | |

| Abdominal pain | 0.816 | |||||

| Yes | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 | 0 | |

| No | 4 (14.3) | 7 (25.0) | 14 (50.0) | 3 (10.7) | 0 | |

| Tenesmus | 0.516 | |||||

| Yes | 1 (20.0) | 2 (40.0) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (20.0) | 0 | |

| No | 3 (12.0) | 6 (24.0) | 14 (56.0) | 2 (8.0) | 0 | |

| Diarrhea | < 0.0011 | |||||

| Yes | 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| No | 0 | 3 (14.3) | 15 (71.4) | 3 (14.3) | 0 |

Both the endoscopic and histological findings showed that 100% of the patients developed DC following the ileostomy creation. This figure exceeds the rates reported in Western populations (91% and 76%)[5,8]. The symptoms previously associated with DC include mucous discharge, rectal bleeding, abdominal pain and tenesmus[5]. We can check for diarrhea in patients with normal bowel continuity of bowel, but in patients with an ileostomy, we cannot. We expected that diarrhea would occur in DC after the ileostomy reversal as it commonly occurs in other forms of colitis (ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s colitis and ischemic colitis). We tested this hypothesis using a questionnaire concerning symptoms, including diarrhea, with a study group that excluded the patients with inflammatory bowel disease and ischemic colitis.

DC symptom rates vary from 6% to 48%, although the overall occurrence is low[5,12,13]. Nineteen patients (63.3%) in our study had at least one symptom after ileostomy creation, and the incidence of symptoms after the ileostomy reversal was 46.6%. Thus, the incidence appears to have decreased slightly; however, these rates represent a dynamic situation. The current analysis showed that mucous discharge, bleeding, abdominal pain and tenesmus resolved, in 11 of 12 patients, 4 of 5 patients, all of 4 patients and 6 of 9 patients, respectively, after the ileostomy reversal. Most of the symptoms disappeared; however, the symptoms experienced after the ileostomy reversal were either were continued or new but likely not caused by DC. For example, after the ileostomy reversal, 6 patients reported tenesmus; it was a new symptom in 3 patients and continued in 3 patients. Tenesmus can occur as the result of the rectal resection itself. Some authors have suggested that tenesmus resulted from altered motility and the reservoir function of the neorectum[14]. Considering the lack of a relationship between the DC symptoms (except diarrhea), and DC severity in this study, we assume that it is difficult to judge DC severity by these symptoms, particularly in patients with a temporary ileostomy. The endoscopic and histological findings, indicate that the inflammatory changes in DC resolve quickly after intestinal continuity is reestablished[5]. Some authors report normal sigmoidoscopy within 2 mo after restoring colonic continuity[4]. The patients in our study still had mild DC 5-6 mo after the ileostomy reversal. Therefore, the time to complete resolution of DC may vary and may not be predictable. To confirm this hypothesis, further evaluation is needed.

We must consider more active treatment selectively in symptomatic patients who have severe endoscopic/histological findings. There are two options for treating of symptomatic DC. DC symptoms may persist in patients with a permanent stoma. One patient with hemiplegia, for whom stoma reversal was not feasible, underwent rectal resection for severe DC[15]. Surgical treatment may have been appropriate here, but other studies show that medical treatment may also be effective. Early studies suggested that a deficiency of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in the excluded colon would contributes to DC[1]. Bacteria produce SCFAs as byproducts of carbohydrate fermentation in the colonic lumen, and SCFAs provide the primary energy source for colonic mucosal cells[15]. Some authors even argue that SCFAs enema may improve the symptoms and endoscopic findings[1]. In human neutrophils, SCFAs reduce the production of reactive oxygen species, which are the agents of oxidative tissue damage[16]. Therefore, SCFAs may be applicable to symptomatic DC patients who have temporary ileostomies.

The current study showed that there were no severe DC symptoms in the patients who had temporary ileostomies. This finding explains why the patients easily endured the ileostomy or, even though they were developed, and were able to wait for timing of ileostomy reversal after clinician’s explanation. Most clinicians can predict which symptoms, may not merit treatment clinically.

Patients may not demand active treatment for other symptoms, but they will for diarrhea. The diarrhea appeared soon after the ileostomy reversal, and continued for a minimum of 3 wk and a maximum of 8 wk in this study. Most clinicians previously thought of diarrhea as low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) and others mistook it for a symptom of general enterocolitis. Most of the patients complained of anal skin irritation, lethargy and nervousness. Some went so far as to continue with a stoma rather than have their ileostomy reversed. In the present study, the patients who had diarrheal symptoms and no signs of obstruction could obtain some degree of control with anti-diarrheal agents such as loperamide.

Several factors may affect functional outcome and in QoL of rectal cancer. Hoerske et al[11] reported that patients diagnosed with lower rectal cancer have lower QoL score than those with upper and middle rectal cancer because of the smaller reservoir volume. Low anterior resection (LAR) for rectal cancer can leads to severe bowel dysfunction with fecal frequency, urgency and incontinence[17-19]. Other evidence suggests that patients who receive preoperative radiotherapy have a higher rate of urgency, diarrhea and fecal incontinence[20,21]. Therefore, we excluded the patients who received preoperative radiotherapy to limit the confusion with DC symptoms. Generally, radiation therapy can be used as local treatment for rectal cancer. Simunovic et al[22] reported that the local recurrence rate of rectal cancer was 6% in a preoperative radiation group vs 3% in a non-radiation group. This rate may indicate that radiation therapy can be omitted if surgery is performed on the proper surgical plane with exact preoperative evaluation of the mesorectal fascia. In this study, most of the patients with locally advanced cancer already had lymph node metastases within the mesorectal fascia in the preoperative evaluation. In the United States, however, postoperative chemoradiation therapy has been the standard treatment because of improved local control, without any effect on the overall survival rate[23]. In this study, the patients an advanced cancer stage, underwent chemotherapy only. Hypoxia in the post-surgical bed requires more radiation dose than preoperative state. Postoperative radiation can increase the possibility of acute and chronic gastrointestinal toxicities, such as radiation enterocolitis (including proctitis) and adhesions affecting the small bowel[24]. These events can negatively affect a patient’s QoL. Postoperative complications such as anastomotic leakage after LAR can also result in poor long-term functional outcomes[9].

Although some important factors in functional outcome or QoL in this context are known, the role of DC after restoration of fecal movement is unknown. We conducted this study for this reason. The nine patients who developed diarrhea after the ileostomy reversal subsequently reported a moderate to large decrease in QoL. Most of the other symptoms did not correlate with the QoL. Diarrhea was also the only symptom that showed a significant correlation with the severity of DC; hence, we suggest that severe DC can be predicted by the occurrence of diarrhea alone after an ileostomy reversal. In the clinical environment, we propose that clinicians continue treatment with SCFA enemas instead of ileostomy reversal in patients with severe DC.

There are a few limitations in this study. First, the small sample size limited the statistical significance of our findings. Second, we did not use a validated questionnaire, such as the Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life score analyzing multidimensional aspects that can indirectly reflect QoL. However, considering that the effectiveness of a questionnaire as a data collection tool depends on the nature of the study and the age of patients, we believe that modification of the questionnaire is needed. Third, 25 patients developed LARS with fecal frequency, urgency or incontinence after rectal cancer surgery. During the survey, most patients mistook fecal frequency or urgency for diarrheal symptom. Diarrhea is generally defined as the passage of abnormally liquid stool at an increased frequency, exceeding 200 g/d[25]. Although we tried to survey using an accurate definition, it was difficult to measure the total amount of stool per day. Future studies with a larger sample size, such as a multi-variate analysis of risk factors will be required to ascertain the relationship between LARS and diarrheal symptom. Finally, the pathogenesis of DC has been little reported until now. Some authors suggested that nitrate-reducing bacteria was found to be increased in the colon that is not receiving fecal flow[26]. We are investigating this issue at our hospital based on the hypothesis that differences in the colonic bacterial spectra may play a role in this variation.

In conclusion, in this study of South Korean patients diagnosed with rectal cancer, we observed a higher incidence of DC after temporary ileostomy than that reported for patients in Western countries. This is also the first study to indicate that DC after a temporary ileostomy may adversely affect patient QoL. The severity of DC after the closure of a diverting stoma appeared to influence patient QoL, primarily by causing diarrhea.

Up to now, the incidence of diversion colitis (DC) in western countries has been published in English literature, but not yet in eastern. Theorectically, DC can happen to patients with ileostomy after low anterior resection (LAR) in rectal cancer, in which patient’s quality of life (QoL) after rectal resection is not only related to the remnant rectal length, but can be hypothesized to related to DC.

Studies regarding the DC have mainly been limited to analyze clinicopathologic finding after surgical situation of the benign disease. Therefore, in patients with temporary ileostomy after LAR in rectal cancer, it would be great interest to examine the DC incidence in Asia and to evaluate if the severity of DC is related to patient’s QoL after the ileostomy reversal.

The results of this study showed that DC developed in all patients with ileostomy after LAR and the symptoms in the period of diverting stoma were not correlated with severity of DC. But, diarrhea after the ileostomy reversal was related to the severity of DC.

There is a need to take notice of DC effect on the patient’s QoL in rectal cancer. Severity of DC before an ileostomy reversal in rectal cancer can predict the patient’s QoL after an ileostomy reversal and lead the patients into proper education and more intensive management. Also, on the base of this result, clinicians need to proceed the further study to clarify why the severity of DC is variable between the individual with patient’s symptoms and impact QoL.

DC is defined as the surgical interruption of fecal flow induce inflammation in the non-functional region of the distal colon and this is characterized that the inflammation typically can resolve when the fecal passage resumes.

This paper is very well written in spite of a small sample size and has a possible message that the severity of DC seems to have an influence on patient’s QoL, particularly on diarrhea, after reversal of a diverting stoma.

P- Reviewer Benjamin P S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Harig JM, Soergel KH, Komorowski RA, Wood CM. Treatment of diversion colitis with short-chain-fatty acid irrigation. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:23-28. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Roe AM, Warren BF, Brodribb AJ, Brown C. Diversion colitis and involution of the defunctioned anorectum. Gut. 1993;34:382-385. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Ferguson CM, Siegel RJ. A prospective evaluation of diversion colitis. Am Surg. 1991;57:46-49. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Glotzer DJ, Glick ME, Goldman H. Proctitis and colitis following diversion of the fecal stream. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:438-441. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Whelan RL, Abramson D, Kim DS, Hashmi HF. Diversion colitis. A prospective study. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:19-24. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Haque S, Eisen RN, West AB. The morphologic features of diversion colitis: studies of a pediatric population with no other disease of the intestinal mucosa. Hum Pathol. 1993;24:211-219. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Grant NJ, Van Kruiningen HJ, Haque S, West AB. Mucosal inflammation in pediatric diversion colitis: a quantitative analysis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;25:273-280. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Orsay CP, Kim DO, Pearl RK, Abcarian H. Diversion colitis in patients scheduled for colostomy closure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:366-367. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Hallböök O, Sjödahl R. Anastomotic leakage and functional outcome after anterior resection of the rectum. Br J Surg. 1996;83:60-62. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Dahlberg M, Glimelius B, Graf W, Påhlman L. Preoperative irradiation affects functional results after surgery for rectal cancer: results from a randomized study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:543-549; discussion 549-551. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Hoerske C, Weber K, Goehl J, Hohenberger W, Merkel S. Long-term outcomes and quality of life after rectal carcinoma surgery. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1295-1303. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Haas PA, Fox TA, Szilagy EJ. Endoscopic examination of the colon and rectum distal to a colostomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:850-854. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Ma CK, Gottlieb C, Haas PA. Diversion colitis: a clinicopathologic study of 21 cases. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:429-436. [PubMed] |

| 14. | van Duijvendijk P, Slors F, Taat CW, Heisterkamp SH, Obertop H, Boeckxstaens GE. A prospective evaluation of anorectal function after total mesorectal excision in patients with a rectal carcinoma. Surgery. 2003;133:56-65. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Murray FE, O’Brien MJ, Birkett DH, Kennedy SM, LaMont JT. Diversion colitis. Pathologic findings in a resected sigmoid colon and rectum. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:1404-1408. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Liu Q, Shimoyama T, Suzuki K, Umeda T, Nakaji S, Sugawara K. Effect of sodium butyrate on reactive oxygen species generation by human neutrophils. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:744-750. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Camilleri-Brennan J, Steele RJ. Quality of life after treatment for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1036-1043. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Camilleri-Brennan J, Ruta DA, Steele RJ. Patient generated index: new instrument for measuring quality of life in patients with rectal cancer. World J Surg. 2002;26:1354-1359. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. Low anterior resection syndrome score: development and validation of a symptom-based scoring system for bowel dysfunction after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2012;255:922-928. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Bruheim K, Guren MG, Skovlund E, Hjermstad MJ, Dahl O, Frykholm G, Carlsen E, Tveit KM. Late side effects and quality of life after radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:1005-1011. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Pollack J, Holm T, Cedermark B, Altman D, Holmström B, Glimelius B, Mellgren A. Late adverse effects of short-course preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2006;93:1519-1525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Simunovic M, Sexton R, Rempel E, Moran BJ, Heald RJ. Optimal preoperative assessment and surgery for rectal cancer may greatly limit the need for radiotherapy. Br J Surg. 2003;90:999-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | NIH consensus conference. Adjuvant therapy for patients with colon and rectal cancer. JAMA. 1990;264:1444-1450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 922] [Cited by in RCA: 837] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Minsky BD, Cohen AM, Enker WE, Kelsen DP, Kemeny N, Frankel J. Efficacy of postoperative 5-FU, high-dose leucovorin, and sequential radiation therapy for clinically resectable rectal cancer. Cancer Invest. 1995;13:1-7. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Thomas PD, Forbes A, Green J, Howdle P, Long R, Playford R, Sheridan M, Stevens R, Valori R, Walters J. Guidelines for the investigation of chronic diarrhoea, 2nd edition. Gut. 2003;52 Suppl 5:v1-15. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Neut C, Guillemot F, Colombel JF. Nitrate-reducing bacteria in diversion colitis: a clue to inflammation? Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:2577-2580. [PubMed] |