Published online Oct 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i39.6645

Revised: June 1, 2013

Accepted: July 4, 2013

Published online: October 21, 2013

AIM: To evaluate the influence of oral Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) on the success of eradication therapy against gastric H. pylori.

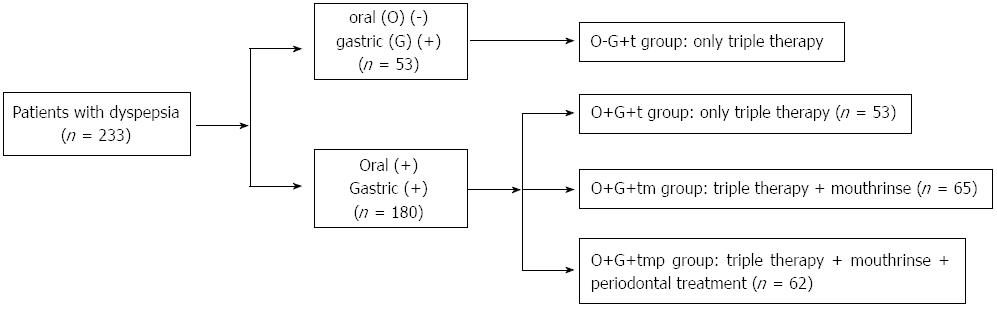

METHODS: A total of 391 patients with dyspepsia were examined for H. pylori using the saliva H. pylori antigen test (HPS), 13C-urea breath test (UBT), gastroscopy, and gastric mucosal histopathological detection. Another 40 volunteers without discomfort were subjected to HPS and 13C-UBT, and served as the control group. The 233 patients who were 13C-UBT+ were enrolled in this study and divided into 4 groups. Patients who were HPS- and 13C-UBT+ (n = 53) received triple therapy alone. Those who were both HPS+ and 13C-UBT+ (n = 180) were randomly divided into 3 groups: (1) the O+G+t group which received triple therapy alone (n = 53); (2) the O+G+tm group which received both triple therapy and mouthrinse treatment (n = 65); and (3) the O+G+tmp group which received triple therapy, mouthrinse, and periodontal treatment (n = 62). The HPS and 13C-UBT were continued for 4 wk after completion of treatment, and the eradication rate of gastric H. pylori and the prevalence of oral H. pylori in the 4 groups were then compared.

RESULTS: The eradication rates of gastric H. pylori in the O-G+t group, the O+G+tm group, and the O+G+tmp group were 93.3%, 90.0%, and 94.7% respectively; all of these rates were higher than that of the O+G+t group (78.4%) [O-G+t group vs O+G+t group (P = 0.039); O+G+tm group vs O+G+t group (P = 0.092); O+G+tmp group vs O+G+t group (P = 0.012); O+G+tm group vs O-G+t group (P = 0.546); O+G+tmp group vs O-G+t group (P = 0.765); O+G+tm group vs O+G+tmp group (P = 0.924)]. The eradication of gastric H. pylori was significantly improved using the combination of triple therapy, mouthrinse, and periodontal treatment. The eradication rates of gastric H. pylori in the peptic ulcer group, chronic atrophic gastritis group and control group were higher than in the duodenitis group and the superficial gastritis group. The prevalence rates of oral H. pylori in the O-G+t group, O+G+t group, O+G+tm group and O+G+tmp group following treatment were 0%, 76.5%, 53.3%, and 50.9%, respectively [O-G+t group vs O+G+t group (P < 0.0001); O+G+tm group vs O+G+t group (P = 0.011); O+G+tmp group vs O+G+t group (P = 0.006); O+G+tm group vs O-G+t group (P < 0.0001); O+G+tmp group vs O-G+t group (P < 0.0001); O+G+tm group vs the O+G+tmp group (P = 0.790)]. Both mouthrinse and periodontal treatment significantly reduced the prevalence of oral H. pylori.

CONCLUSION: Mouthrinse treatment alone or combined with periodontal treatment can, to some extent, reduce the prevalence of oral H. pylori and improve the eradication rate of gastric H. pylori.

Core tip: The average eradication rate of gastric Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) has decreased in recent years. However, some foreign studies have shown that the eradication rate of gastric H. pylori may be improved by eliminating the presence of oral H. pylori rather than increasing the dose of antibiotics. In most studies, H. pylori DNA was detected and used to confirm oral H. pylori infection, and later determine whether professional periodontal treatments were effective in killing oral H. pylori. To avoid the expensive and complicated techniques involved with this approach, the current study used a cost-effective and simple method to test for and eliminate oral H. pylori. This method can be used to prove the elimination of gastric H. pylori, and is practical for use in the clinic.

-

Citation: Song HY, Li Y. Can eradication rate of gastric

Helicobacter pylori be improved by killing oralHelicobacter pylori ? World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(39): 6645-6650 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i39/6645.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i39.6645

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is believed to be one of the major factors responsible for chronic active gastritis, gastroduodenal ulcers, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas, and gastric cancers[1]. It was designated as a type I carcinogen by the World Health Organization in 1994 and approximately 50% of the world’s population is infected. The isolation of H. pylori from dental plaque by Krajde[2] in 1989 strongly suggested that both oral-oral and gastro-oral routes are important transmission modes of H. pylori, and that the oral cavity is an extra-gastric reservoir for H. pylori[3-6]. Several studies have suggested that oral H. pylori is associated with the presence of gastric H. pylori[6,7]; additionally, patients who are oral H. pylori-positive have a lower success rate of gastric H. pylori eradication than patients who test negative for oral H. pylori[6,8,9]. Also, previous studies have shown that DNA samples obtained from oral H. pylori are very similar to those obtained from corresponding gastric H. pylori[10-12]. The prevalence of oral H. pylori is related to an individual’s quality of oral hygiene and periodontal status, such as the presence of dental plaque and periodontal pockets[13], and the eradication rate of gastric H. pylori can be increased by controlling dental plaque and improving oral hygiene[14,15]. In our study, the saliva H. pylori antigen test (HPS) and the 13C-urea breath test (13C-UBT) were used to detect oral and gastric H. pylori infections, respectively, and in this report, the term HPS+ signifies the presence of oral H. pylori infection, while 13C-UBT+ signifies the presence of gastric H. pylori infection. 13C-UBT+ patients were recruited for this study. HPS- cases were treated with triple therapy alone, while HPS+ cases were randomly distributed into 3 groups which received different treatments. The goal of this study was to evaluate the influence of oral H. pylori on the success of eradication therapy against gastric H. pylori.

From August 2011 to July 2012, outpatients with dyspepsia seen at the Department of Gastroenterology, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China, were recruited and selected for this study. Exclusion criteria included a past history of H. pylori eradication therapy; treatment with antibiotics, H2 receptor blockers, bismuth or proton pump inhibitors within one month of study enrollment; the presence of severe periodontal disease; presence of an immune disease; current pregnancy; age < 18 years; and the use of immune depressant drugs. A total of 391 eligible patients were enrolled in the study and another 40 volunteers without discomfort were enrolled to serve as a control group (Table 1).

| Diseases | Total | Male | Female | Age range (yr) | Mean age (yr) |

| Peptic ulcer | 54 | 40 | 14 | 20-80 | 51.1 |

| Chronic atrophic gastritis | 48 | 32 | 16 | 46-82 | 58.5 |

| Duodenitis | 58 | 31 | 27 | 26-77 | 51.0 |

| Superficial gastritis | 231 | 95 | 136 | 18-74 | 49.6 |

| Control group | 40 | 17 | 23 | 18-67 | 44.0 |

The diseases listed in Table 1 were diagnosed using the following criteria: Peptic ulcer was defined as the presence of gastric ulcer and/or duodenal ulcer. Chronic atrophic gastritis: Endoscopy showed good visualization of the submucosal vessel in the antrum and in the body. Histopathology showed the loss of appropriate glands or the presence of metaplasia. Duodenitis: During endoscopy, the duodenal bulb mucosa appeared abnormally congested, edematous, or roughened in the absence of an ulcer or scar. Histopathology showed nuclear atypia of the glandular epithelium and infiltration by neutrophils. Superficial gastritis: During endoscopy, gastric mucosa appeared abnormally congested, edematous, or roughened. Histopathology showed nuclear atypia of the glandular epithelium and infiltration by neutrophils.

Each subject was evaluated by HPS, 13C-UBT, gastroscopy, and gastric mucosal histopathological examination. Two biopsy specimens were taken from the greater curvature of both the antrum and the body of the stomach, respectively. Another 2 biopsy specimens were taken from both the lesser curvature of the antrum and body, respectively. Patients who were HPS- and 13C-UBT+ (n = 53) received triple therapy alone. Those who were both HPS+ and 13C-UBT+ (n = 180) were randomly divided into 3 groups: (1) the O+G+t group which received triple therapy alone (n = 53); (2) the O+G+tm group which received triple therapy and mouthrinse treatment (n = 65); and (3) the O+G+tmp group which received triple therapy, mouthrinse, and periodontal treatment (n = 62). The triple therapy consisted of amoxicillin (1.0 g) and esomeprazole (20 mg), twice a day, and levofloxacin (0.5 g), once a day, given for 10 d. Mouthrinse (brand name Chlorhexidine Gargle), (Shenzhen Nanyue Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) was purchased from a drugstore. This mouthwash contained 0.02% tinidazole and 0.12% chlorhexidine, and a 20 mL volume was held in the mouth for 5 min and then spat out, for 10 d. Periodontal therapy consisted of plaque and calculus removal with an ultrasonic device twice a month in the Department of Stomatology, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University. HPS and 13C-UBT testing were conducted 4 wk after triple therapy was completed. A flow-chart of patient treatment is shown in Figure 1.

The saliva H. pylori antigen test (Meili Taige Diagnostic Reagent Co., Ltd, Jiaxing, China) is a rapid immunochromatographic assay that uses antibody-coated colloidal gold to detect the presence of specific H. pylori antigens in the saliva specimen. Yee et al[16] clarified that HPS was designed to detect two H. pylori antigens: flagellin and urease. In Yee’s experiment, the HPS results were compared in parallel with the UBT, serum antibody, Campylobacter-like organism test, silver stain, culture, and stool antigen test results. The test’s sensitivity was 10 ng/mL H. pylori flagellin and urease antigen. There was no interference or cross-reactivity with the other bacteria in the oral cavity and there was statistical correlation between oral antigen and serum antibody test results. No food or drink was allowed 1 h before the test. To perform the test, four drops of saliva were added to the sampling cup using a pipette and two drops of PBS were added. After mixing, a new pipette was used to transfer four drops of the mixture into the sample well of the test cassette. The sample flowed through a label pad containing H. pylori antibody coupled to red-colored colloidal gold. If the sample contained H. pylori antigens, the antigen would bind to the antibody coated on the colloidal gold particles to form antigen-antibody-gold complexes. The complexes then moved on a nitrocellulose membrane by capillary action toward the test zone. A second control line always appeared in the result window to indicate that the test had been correctly performed and that the test device was functioning properly. The results were observed within 5-30 min. The occurrence of two bands in the test and control zones was positive for H. pylori. The occurrence of one band in the control zone was negative for H. pylori. If there was no band in the control zone, the samples were re-tested.

An HG-IRIS13C infrared spectrometer and diagnostic kits (Beijing Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd) were used to detect gastric H. pylori. The test was judged positive when the detected value in the exhalation was larger than 4.

Statistical analysis of data was performed with SPSS software 19.0. The χ2 test was used to analyze the eradication rate of gastric H. pylori and the prevalence of oral H. pylori in each group. A P value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 431 patients were tested using HPS and 13C-UBT methods, and the results are shown in Table 2.

| HPS | 13C-UBT | |

| Positive | Negative | |

| Peptic ulcer (n = 54) | ||

| Positive | 29 (53.7) | 8 (14.8) |

| Negative | 14 (25.9) | 3 ( 5.6) |

| Chronic atrophic gastritis (n = 48) | ||

| Positive | 24 (50.0) | 14 (29.1) |

| Negative | 8 (16.7) | 2 ( 4.2) |

| Duodenitis (n = 58) | ||

| Positive | 35 (60.3) | 16 (27.6) |

| Negative | 2 ( 3.4) | 5 (8.7) |

| Superficial gastritis (n = 231) | ||

| Positive | 79 (34.2) | 89 (38.5) |

| Negative | 25 (10.8) | 38 (16.5) |

| Control group (n = 40) | ||

| Positive | 12 (30.0) | 21 (52.5) |

| Negative | 5 (12.5) | 2 ( 5.0) |

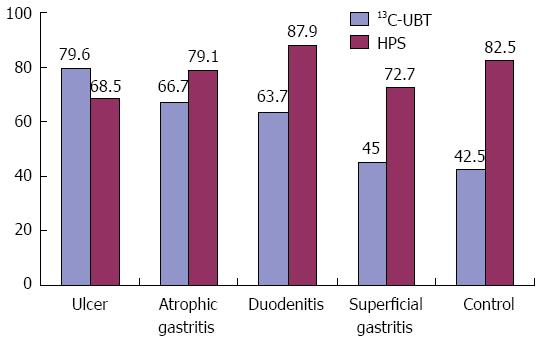

The prevalence of gastric and oral H. pylori differed among the 5 disease groups. There was a reduced trend for the prevalence of gastric H. pylori starting from the peptic ulcer group and continuing to the control group, but no similar trend was seen for oral H. pylori (Figure 2).

Four weeks after completion of treatment, 213 patients returned for evaluation, and 20 patients did not return. The gastric H. pylori eradication rate in the O+G+t group was significantly lower than in the O-G+t and O+G+tmp groups (O-G+t group vs O+G+t group, P = 0.039), (O+G+tmp group vs O+G+t group, P = 0.012). The gastric H. pylori eradication rate in the O+G+tm group was higher than in the O+G+t group, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.092). There were no statistical differences between the O-G+t and O+G+tm groups when compared to the O+G+tmp group (O+G+tm group vs O-G+t group, P= 0.546), O+G+tmp group vs O-G+t group, P = 0.765), and O+G+tm group vs O+G+tmp group, P = 0.924) (Table 3).

There were some subtle differences in the rate of gastric H. pylori eradication between the different gastric disease groups. The eradication rates in the peptic ulcer and chronic atrophic gastritis groups were higher than those in the duodenitis and superficial gastritis groups, but the differences were not statistically significant (Table 4).

| Group | Gastric diseases | ||||

| Peptic ulcer | Chronic atrophic gastritis | Duodenitis | Superficial gastritis | Control group | |

| O-G+t | 10 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 2 (100.0) | 19 (86.4) | 5 (100.0) |

| O+G+t | 9 (90.0) | 7 (87.5) | 8 (72.7) | 12 (70.6) | 4 (80.0) |

| O+G+tm | 9 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | 9 (75.0) | 22 (88.0) | 4 (100.0) |

| O+G+tmp | 9 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) | 10 (91.0) | 27 (93.1) | 3 (100.0) |

After treatment, the prevalence of oral H. pylori in the O+G+t group was significantly higher than those in the other 3 groups: O-G+t group vs O+G+t group (P < 0.0001), O+G+tm group vs O+G+t group (P = 0.011), and O+G+tmp group vs O+G+t group (P = 0.006). There was no significant difference between the O+G+tm and O+G+tmp groups (P = 0.790) (Table 3).

The idea that H. pylori can be transmitted by both oral to oral and stomach to oral routes has been recognized since 1989 when Krajde first isolated H. pylori from the dental plaque of patients with gastric diseases related to H. pylori infection. Further studies have shown that the gastric H. pylori eradication rate in patients with oral H. pylori infection is lower than that in patients without oral H. pylori infection. With the increase in antibiotic resistance which has occurred during the past 10 years, the rate of gastric H. pylori eradication following triple therapy has significantly decreased. From 1983-1997, the average eradication rate for gastric H. pylori was 75%-90%[17], but later decreased to 68.8% in the period from 1996 to 2005[18]. Improvements in the gastric H. pylori eradication rate produced by killing oral H. pylori can reduce the application of antibiotics[9,14], which not only reduces the economic burden of treatment, but also lowers the risk of increasing the resistance of H. pylori to antibiotics. Oral H. pylori is mainly present in periodontal pockets and dental plaque[19,20]. Zaric et al[9] collected dental plaque and gastric tissues and examined them for H. pylori using nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR). In our study, for patients with both oral and gastric H. pylori, periodontal treatment was applied in addition to triple therapy. Ultrasonic waves were used to remove dental plaque and calculi, and root surface scaling was used to eradicate the periodontal pockets. Glucose chlorhexidine solution (0.15%) was used to lavage the periodontal pocket. After periodontal treatment, the gastric H. pylori eradication rate was increased from 47.6% to 77.3%, while the prevalence of oral H. pylori was decreased from 66.7% to 27.0%; these results indicated that periodontal treatment could kill oral H. pylori. The methods used by Zaric were useful, but not easy to employ, and the monetary cost was high. Conducting nested PCR requires specific instruments, and the periodontal treatment also requires experienced dentists; therefore, these methods are not practical for routine clinical application. The current study was conducted to seek a cost-effective method for diagnosing oral H. pylori infection and reducing its prevalence.

Currently, there are two methods (bacterial culturing and nested PCR) used to diagnose oral H. pylori infection. Although the bacterial culture method has high specificity, large numbers of other oral bacteria can inhibit the growth of H. pylori, leading to a high false negative rate[21]. The nested PCR method has high sensitivity and specificity, but the results have been highly variable due to the use of different primers, and it cannot differentiate between DNA from dead and living bacteria. H. pylori DNA can still be detected even if the bacteria are already dead[22,23]. Thus, the nested PCR method cannot monitor the therapeutic efficacy of a treatment for oral H. pylori.

The HPS test is a rapid immunochromatographic assay. The principle of this test kit is based on using a colloidal gold chromatography double antibody sandwich to detect H. pylori flagellae and urease in human saliva. There are no cross-reactions with the urease released by other oral bacteria[14].

Our results showed that the positive rate of HPS testing was 74.9%, demonstrating that the mouth is another storage site for H. pylori. In this study, the gastric H. pylori eradication rate in patients who were HPS+ was lower than that in patients who were HPS- (78.4% vs 93.3%). We also noted that the test results of gastric and oral H. pylori were not consistent. Previous studies have shown that H. pylori does not colonize in the mouth of a person who practices good oral hygiene (e.g., no periodontal disease, no gingival band or plaque)[24]. In this situation, the oral H. pylori titer is low and does not reach the threshold of gastric H. pylori infection. Therefore, a test to detect gastric H. pylori infection would give negative results. For gastric H. pylori-positive patients with good oral hygiene, although gastric H. pylori may be refluxed into the mouth, the bacterium may not survive in the mouth. In this study, the HPS test had a high sensitivity, which enabled it to detect a low titer of H. pylori. Therefore, the positive rate for oral H. pylori infection was higher than that for gastric H. pylori infection.

H. pylori in the oral cavity is covered by a special protective shell called a biofilm, and systemic eradication therapy may not be very effective when used for treatment[25,26]; this study confirmed that hypothesis. The gastric H. pylori eradication rate in the O+G+t group was much higher than that in the oral H. pylori group (78.4% vs 23.5%). Compared with the O+G+t group, the eradication rates of gastric H. pylori in the O+G+tm and O+G+tmp groups were elevated from 78.4% to 90.0% and 94.7%, respectively, while the prevalence of oral H. pylori was reduced from 76.5% to 53.3% and 50.9%, respectively. There was no significant difference in gastric H. pylori eradication rate between the O+G+tm group and the O+G+tmp group. The gastric H. pylori eradication rates in the peptic ulcer group, chronic atrophic gastritis group, and control group were higher than those in the duodenitis group and superficial gastritis group, but no conclusion could be drawn from this finding because the number of patients was small. This study demonstrated that mouthrinse treatment alone or combined with periodontal treatment could effectively reduce the prevalence of oral H. pylori, but did not prove a mechanism for this result. One hypothesis may be that the mouthrinse treatment or periodontal treatment reduced the amount of dental plaque and improved oral hygiene, thus enabling the titer of H. pylori to be reduced.

This study proved that mouthrinse treatment alone or combined with periodontal treatment could reduce the prevalence of oral H. pylori and improve the eradication rate of gastric H. pylori. The HPS test is a simple and rapid method that can diagnose oral H. pylori infection; however, the test results cannot be analyzed quantitatively. Therefore, the therapeutic effect of various treatments could not be thoroughly analyzed.

It is well acknowledged that the stomach can serve as a reservoir for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) and that gastric H. pylori can be killed by triple or quadruple therapy. Increasing numbers of studies have suggested that the average eradication rate of gastric H. pylori has dropped in recent years, and it is important to find a practical way to improve the eradication rate.

Since Krajde isolated H. pylori from dental plaque in 1989, many studies have demonstrated that the oral cavity serves as an extra-gastric reservoir for H. pylori. Several studies have suggested that patients who test positive for oral H. pylori have a lower success rate of gastric H. pylori eradication than oral H. pylori-negative individuals. Zaric used nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to test for the presence of oral H. pylori, and improved the eradication rate of gastric H. pylori from 47.6% to 77.3% by removing dental plaque. However, the cost of this procedure was high and the process was complicated. There is a great need to find a simple and rapid diagnostic test that can be used to confirm the presence of oral H. pylori infection, and to identify a method that can increase the eradication rate of gastric H. pylori and is feasible for clinical application.

13C-UBT is the gold standard for diagnosis of gastric H. pylori infection; however, a unified method has not been identified for diagnosing oral H. pylori infection. Nested PCR, which tests the DNA of H. pylori, is commonly used, but has a high false positive rate because it cannot distinguish between DNA from dead and living bacteria. The current study replaced the nested PCR method with a saliva H. pylori antigen test (HPS) to test for oral H. pylori. The HPS test employs a monoclonal antibody that was developed against semipurified H. pylori protein, and in another experiment, this test showed no interference or cross reactivity with other oral bacteria. Zaric killed oral H. pylori by removing dental plaque and lavaging the periodontal pocket, which required a professional dentist. In the current study, mouthwash was used to effectively kill oral H. pylori.

This study used the saliva H. pylori antigen test to diagnose oral H. pylori infection. This test is simple to use and results are rapidly obtained. The eradication rate of gastric H. pylori improved significantly in patients who received mouthrinse treatment alone or combined with periodontal treatment. This innovative approach can not only reduce the economic burden of patients, but also decrease the development of resistance to antibiotics.

H. pylori: H. pylori is a spiral rod-shaped bacterium that mainly colonizes the epithelium of the stomach. It is considered to be the main cause of peptic ulcer, chronic active gastritis, gastroduodenal ulcer, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and gastric cancer. Approximately half of the world’s population is infected. Triple therapy which consists of one proton inhibitor and two antibiotics is often used to kill H. pylori.

This is an interesting study, indicating a cheap way of improving H. pylori eradication rate. The study was performed on 391 persons who underwent gastroscopy and histopathological examination of gastric mucosa. For evaluation of H. pylori in oral cavity, the authors used H. pylori saliva test based on detection of H. pylori antigen in saliva using rapid immunochromatographic assay. For evaluation of H. pylori in stomach mucosa, the authors used 13C-urea breath test. The results showed that the eradication of H. pylori in the mouth cavity using mouth rinse and peridental treatment could kill the oral H. pylori and improve the eradication rate of gastric H. pylori by triple therapy. The study is set up correctly. The paper is written well. The Introduction gives a good overview of the study background and the authors raised clearly the aim of the study. The material studied is large enough to draw the conclusions. The Tables and Figure give a good overview about the results.

P- Reviewers Linden SK, Tosetti C, Vorobjova T, Wang JT S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Ma S

| 1. | Correa P. Helicobacter pylori as a pathogen and carcinogen. J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997;48 Suppl 4:19-24. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Krajden S, Fuksa M, Anderson J, Kempston J, Boccia A, Petrea C, Babida C, Karmali M, Penner JL. Examination of human stomach biopsies, saliva, and dental plaque for Campylobacter pylori. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1397-1398. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Chow TK, Lambert JR, Wahlqvist ML, Hsu-Hage BH. Helicobacter pylori in Melbourne Chinese immigrants: evidence for oral-oral transmission via chopsticks. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;10:562-569. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mégraud F. Transmission of Helicobacter pylori: faecal-oral versus oral-oral route. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9 Suppl 2:85-91. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Cellini L, Grande R, Artese L, Marzio L. Detection of Helicobacter pylori in saliva and esophagus. New Microbiol. 2010;33:351-357. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Zou QH, Li RQ. Helicobacter pylori in the oral cavity and gastric mucosa: a meta-analysis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2011;40:317-324. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 62] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Al Asqah M, Al Hamoudi N, Anil S, Al Jebreen A, Al-Hamoudi WK. Is the presence of Helicobacter pylori in dental plaque of patients with chronic periodontitis a risk factor for gastric infection? Can J Gastroenterol. 2009;23:177-179. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Miyabayashi H, Furihata K, Shimizu T, Ueno I, Akamatsu T. Influence of oral Helicobacter pylori on the success of eradication therapy against gastric Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2000;5:30-37. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 88] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zaric S, Bojic B, Jankovic Lj, Dapcevic B, Popovic B, Cakic S, Milasin J. Periodontal therapy improves gastric Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Dent Res. 2009;88:946-950. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Assumpção MB, Martins LC, Melo Barbosa HP, Barile KA, de Almeida SS, Assumpção PP, Corvelo TC. Helicobacter pylori in dental plaque and stomach of patients from Northern Brazil. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3033-3039. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang J, Chi DS, Laffan JJ, Li C, Ferguson DA, Litchfield P, Thomas E. Comparison of cytotoxin genotypes of Helicobacter pylori in stomach and saliva. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1850-1856. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Banatvala N, Lopez CR, Owen R, Abdi Y, Davies G, Hardie J, Feldman R. Helicobacter pylori in dental plaque. Lancet. 1993;341:380. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 66] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wichelhaus A, Brauchli L, Song Q, Adler G, Bode G. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in the adolescent oral cavity: dependence on orthodontic therapy, oral flora and hygiene. J Orofac Orthop. 2011;72:187-195. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jia CL, Jiang GS, Li CH, Li CR. Effect of dental plaque control on infection of Helicobacter pylori in gastric mucosa. Tex Dent J. 2012;129:1069-1073. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Shmuely H, Yahav J, Samra Z, Chodick G, Koren R, Niv Y, Ofek I. Effect of cranberry juice on eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients treated with antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51:746-751. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yee KC, Wei MH, Yee HC, Everett KD, Yee HP, Hazeki-Talor N. A screening trial of Helicobacter pylori-specific antigen tests in saliva to identify an oral infection. Digestion. 2013;87:163-169. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Laheij RJ, Rossum LG, Jansen JB, Straatman H, Verbeek AL. Evaluation of treatment regimens to cure Helicobacter pylori infection--a meta-analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:857-864. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 189] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kadayifci A, Buyukhatipoglu H, Cemil Savas M, Simsek I. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori with triple therapy: an epidemiologic analysis of trends in Turkey over 10 years. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1960-1966. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Song Q, Lange T, Spahr A, Adler G, Bode G. Characteristic distribution pattern of Helicobacter pylori in dental plaque and saliva detected with nested PCR. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:349-353. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Agarwal S, Jithendra KD. Presence of Helicobacter pylori in subgingival plaque of periodontitis patients with and without dyspepsia, detected by polymerase chain reaction and culture. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:398-403. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ferguson DA, Li C, Patel NR, Mayberry WR, Chi DS, Thomas E. Isolation of Helicobacter pylori from saliva. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2802-2804. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Eskandari A, Mahmoudpour A, Abolfazli N, Lafzi A. Detection of Helicobacter pylori using PCR in dental plaque of patients with and without gastritis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2010;15:e28-e31. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Ricci C, Holton J, Vaira D. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori: invasive and non-invasive tests. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;21:299-313. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 135] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Song Q, Spahr A, Schmid RM, Adler G, Bode G. Helicobacter pylori in the oral cavity: high prevalence and great DNA diversity. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:2162-2167. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Wilson M. Susceptibility of oral bacterial biofilms to antimicrobial agents. J Med Microbiol. 1996;44:79-87. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 197] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pytko-Polonczyk J, Konturek SJ, Karczewska E, Bielański W, Kaczmarczyk-Stachowska A. Oral cavity as permanent reservoir of Helicobacter pylori and potential source of reinfection. J Physiol Pharmacol. 1996;47:121-129. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |