Published online Sep 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i35.5910

Revised: August 1, 2013

Accepted: August 12, 2013

Published online: September 21, 2013

Processing time: 110 Days and 14.3 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy and safety of paclitaxel-nedaplatin combination as a front-line regimen in Chinese patients with metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC).

METHODS: A two-center, open-label, single-arm phase II study was designed. Thirty-nine patients were enrolled and included in the intention-to-treat analysis of efficacy and adverse events. Patients received 175 mg/m2 of paclitaxel over a 3 h infusion on 1 d, followed by nedaplatin 80 mg/m2 in a 1 h infusion on 2 d every 3 wk until the documented disease progression, unacceptable toxicity or patient’s refusal.

RESULTS: Of the 36 patients assessable for efficacy, there were 2 patients (5.1%) with complete response and 16 patients (41.0%) with partial response, giving an overall response rate of 46.1%. The median progression-free survival and median overall survival for all patients were 7.1 mo (95%CI: 4.6-9.7) and 12.4 mo (95%CI: 9.5-15.3), respectively. Toxicities were moderate and manageable. Grade 3/4 toxicities included neutropenia (15.4%), nausea (10.3%), anemia (7.7%), thrombocytopenia (5.1%), vomiting (5.1%) and neutropenia fever (2.6%).

CONCLUSION: The combination of paclitaxel and nedaplatin is active and well tolerated as a first-line therapy for patients with metastatic ESCC.

Core tip: Esophageal cancers are among the most aggressive tumors with a poor prognosis. Till now, there has been no standard chemotherapy regimen for advanced esophageal cancer. In this paper, we conducted a phase II study on combination chemotherapy consisting of paclitaxel and nedaplatin in previously untreated patients with metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). Our results demonstrated that the combination of two drugs is active and well tolerated as a first-line therapy for patients with recurrent or metastatic ESCC.

- Citation: He YF, Ji CS, Hu B, Fan PS, Hu CL, Jiang FS, Chen J, Zhu L, Yao YW, Wang W. A phase II study of paclitaxel and nedaplatin as front-line chemotherapy in Chinese patients with metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(35): 5910-5916

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i35/5910.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i35.5910

China accounts for about half of the world’s esophageal cancer cases, about 250000 each year, and 85% of the total global incidence occurs in the developing world, according to the World Health Organization report. Overt and incurable metastatic disease is present at diagnosis in 50% of patients. Furthermore, even after curative surgery, local recurrences and/or distant metastases are detected in more than 50% of the patients within 5 years of follow-up[1]. The median survival of patients with metastatic esophageal carcinoma is only 3-8 mo[2]. Palliative chemotherapy may lead to distant tumor and symptom control. The effect of chemotherapy on survival is unclear for lack of large randomized trials. Up till now there has been no global standard regimen for the first-line treatment of advanced disease. Of the available regimens, the regimen containing 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and cisplatin is widely used in China, with RR ranging from 15%-45%[3-5]. However, treatment with 5-FU and cisplatin can induce severe toxicity[6]. What’s more, almost all patients have to be hospitalized for this treatment. Therefore, it is imperative to develop effective and well-tolerated chemotherapeutic agents for treatment.

Recently, paclitaxel, a natural product isolated from the bark of the yew tree Taxus brevifolia, has demonstrated some promising responses against digestive tract cancer. As a single agent, paclitaxel has been reported to achieve a response rate of 32% in esophageal cancer and gastroesophageal junction cancer[7]. Besides, several phase I/II studies have shown that paclitaxel-based regimens have significant activity in patients with locally advanced and metastatic esophageal cancer[8-12]. However, toxicity for combination therapy was significant and included severe myelosuppression, gastrointestinal (GI) and neurologic toxicity, and a significant rate of hospitalization for treatment-related complications. So it is urgent to seek new combination treatments that could achieve similar outcome and induce relatively minimal toxicities.

Nedaplatin cis-diammine-glycolate platinum (NDP) is a new platinum derivative, selected from a series of platinum analogues based on its pronounced preclinical antitumor activity against various solid tumors with lower nephrotoxicity[13]. Preclinical studies indicate that nedaplatin has an antitumor activity comparable to cisplatin[14-16] and has been shown experimentally to overcome cisplatin resistance in a cisplatin-resistant K562 cell line[14]. Clinically, single agent nedaplatin has shown a wide spectrum of antitumor activity, producing the favorable response rates in head and neck[17], esophagus[18], non-small cell lung[19,20], and cervical cancers[21]. These reports prompted us to use a new combination of nedaplatin and paclitaxel for patients with metastatic esophageal carcinoma, because these patients have poorer tolerance, and a less toxic treatment is desirable. The current phase II study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of nedaplatin-paclitaxel combination as a front-line regimen in Chinese patients with metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

This was a two-center, open-label, single-arm phase II study evaluating the efficacy and toxicities of nedaplatin and paclitaxel in patients with metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma who had no previous treatment. The primary end point was response to treatment. Secondary end points were toxicity, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).

Patients aged 18-75 years with measurable target lesion pathologically confirmed advanced or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma were eligible for the study. Prior chemotherapy for advanced disease was not permitted. However, neoadjuvant or concurrent chemotherapy was allowed, provided that the treatment was completed at least 6 mo before the start of the current study. Patients were required to have Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0-2, with a life expectancy ≥ 3 mo, an adequate bone marrow, liver and kidney function, as indicated by an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≥ 1500/μL, a platelet count ≥ 100000/μL, serum creatinine ≤ 2.0 mg/dL, serum bilirubin ≤ 1.5 mg/dL, and serum alanine aminotransferase ≤ 2.5 times higher than the upper limit of the normal (except in those cases with liver involvement when a value ≤ 5 times the upper limit of the normal was accepted). All patients were given written informed consents to participate in this study, which was also approved by the Ethics Committee of two centers.

Patients with evidence of central nervous system metastases, an inability to take oral medication were excluded. Gastroesophageal junction tumors were excluded from the study. Exclusion criteria also included pathologically confirmed adenocarcinoma, prior malignancies (other than non-melanoma skin cancer or in situ cervical cancer) within the previous 5 years, and uncontrolled infection or severe comorbidity such as myocardial infarction within 6 mo or symptomatic heart diseases. Pregnant or lactating women were excluded from the study; women with childbearing potential were required to agree to have adequate contraception.

Patients received 175 mg/m2 of paclitaxel over a 3 h infusion on 1 d, followed by nedaplatin 80 mg/m2 in a 1 h infusion on 2 d every 3 wk until the documented disease progression, unacceptable toxicity or patient’s refusal. These doses were based on a phase I trial of chemotherapy using paclitaxel and nedaplatin in chemotherapy-naive patients with unresectable squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)[22]. Paclitaxel infusions preceded the administration of nedaplatin in the current study, as the interaction of nedaplatin and paclitaxel is highly schedule-dependent[23,24]. As prophylactic agents, dexamethasone (iv 20 mg), promethazine (iv 25 mg) and cimetidine (iv 400 mg) were given 30 min before paclitaxel administration. All patients received adequate antiemetic therapy prior to chemotherapy. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor was administered at physician’s discretion.

All patients were screened for medical history and underwent a physical examination. Complete blood cell count (CBCC) was performed every week, blood biochemical test and electrocardiogram were performed before every cycle. After every two cycles of treatment, response was evaluated by two independent experts using RECIST criteria. Of the lesions observed prior to treatment, a maximum of five measurable lesions from each metastasized organ up to a total of 10 lesions were selected as target lesions. In the cases of partial response (PR) or complete response (CR), a confirmative computed tomography (CT) scan was performed 4 wk later and this was followed by a CT scan after every two treatment cycles. After discontinuation of treatment, follow-up visits were done every 3 mo to document late toxic effects, disease progression and survival. Toxicity was reported using an NCI-CTC version 3.0 toxicity scale.

The dose of paclitaxel was reduced to 150 mg/m2 if one of the following conditions occurred: grade 3 neutropenia with infection, grade 4 neutropenia, grade 3 thrombocytopenia or > grade 3 sensory neurotoxicity. If toxicity persisted, a second dose reduction of paclitaxel to 135 mg/m2 was allowed. In cases of fatigue or asthenia above grade 3, treatment was postponed for 1 wk and restarted when the patient recovered to below grade 2. Patients requiring a delay in therapy for > 2 wk or more than two dose reductions were removed from the study. A new cycle of therapy could begin if the neutrophils count were 1.5 × 109/L, the platelets count were 75 × 109/L, and all relevant nonhematological toxicities were grade 2. Once a dose had been reduced during a treatment cycle, re-escalation was not permitted during any other subsequent cycles.

A Simon’s two stage phase II design was used. The treatment program was designed to reject response rates of 20% and to provide a significance level of 0.05 with a statistical power of 80% to assess the activity of the regimen at a 40% response rate[25]. The upper limit for a first-stage treatment rejection was 4 responses among 18 evaluable patients; the upper limit of second-stage rejection was 10 responses among 33 evaluable patients. Assuming a dropout rate of 20%, a total of 39 patients were required. All enrolled patients were included in the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis of efficacy. Analysis of PFS and overall survival analysis were performed by the Kaplan-Meier method. The PFS was calculated from the initiation of chemotherapy to the date of the disease progression, while overall survival was measured from the initiation of chemotherapy to the date of the last follow-up or death. Statistical data were obtained using an SPSS 11.0 software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

Between June 2008 and July 2010, a total of 39 patients from 2 centers (Including Anhui Provincial Hospital affiliated to Anhui Medical University and Anhui Provincial Cancer Hospital) were enrolled. Their baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

| Characteristics | No. of patients |

| Age, yr (range) | Median 60 (range, 34-72) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 1 (2.6) |

| Male | 38 (97.4) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 4 (10.3) |

| 1 | 32 (82.0) |

| 2 | 3 (7.7) |

| Tumor involved site | |

| Lymph node | 25 (64.1) |

| Lung | 14 (35.9) |

| Liver | 16 (41.0) |

| Bone | 7 (17.9) |

| Number of involved site | |

| 1 | 28 (71.8) |

| 2 | 13 (33.3) |

| ≥ 3 | 4 (10.3) |

| Differentiation | |

| Poor-differentiated | 10 (25.6) |

| Moderate-well differentiated | 23 (59.0) |

| Unknown | 6 (15.4) |

| Prior treatment (cases) | |

| Treatment-naive | 30 (76.9) |

| Radiation | 4 (10.3) |

| Operation | 5 (12.8) |

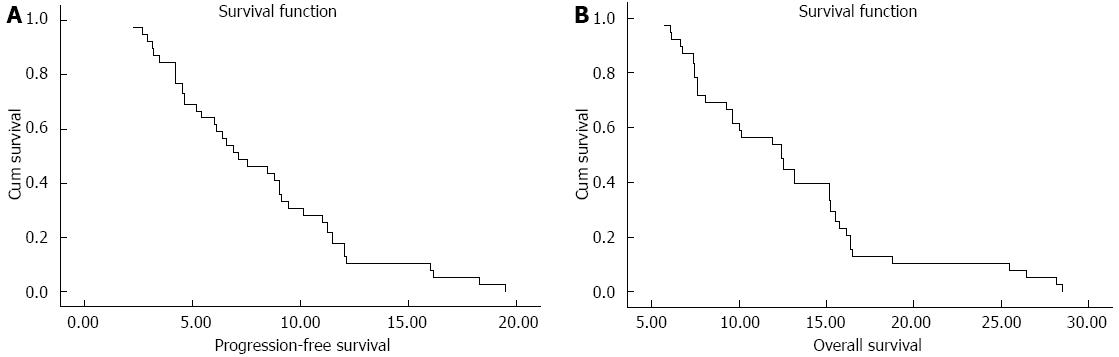

A total of 39 patients were assessable for response (Table 2). Two patients were not evaluated because of loss to follow-up after two courses, and 1 patient withdrew consent because of toxicities after 1 course. Two patients (5.1%) achieved a CR, 16 patients (41.0%) had PR, 15 patients (38.5%) had SD and 3 patients had PD (7.7%). The median follow-up period was 13.1 mo (range 3.3-28.6 mo). The median PFS for all patients was 7.1 mo (95%CI: 4.6-9.7, Figure 1A). The median OS was 12.4 mo (95%CI: 9.5-15.3, Figure 1B), with a 1-year survival rate of 53.8%.

| Response | n = 39 |

| Response rate | |

| Complete response | 2 (5.1) |

| Partial response | 16 (41.0) |

| Stable disease | 15 (38.5) |

| Progressive disease | 3 (7.7) |

| Not assessable | 3 (7.7) |

A total of 141 courses of treatment were given and patients received a median 4 courses (range, 1-6 courses). AE frequencies in this population are listed in Table 3. The most common haematologic AE was leucopenia, which occurred with grade 3/4 in 6 patients (15.4%). Febrile neutropenia was observed in 1 patient (2.6%). Although this case was successfully treated with antibiotics and G-CSF, this patient withdrew his consent after this experience. Grade 3/4 anemia was observed in 3 patients (7.7%) and grade 3 thrombocytopenia in 2 patients (5.1%). Major nonhematologic AEs (in order of decreasing frequency) were nausea (59.0%), fatigue (56.4%), vomiting (46.2%), myalgia (43.6%), alopecia (30.8%), and diarrhea (15.4%). Grade 3/4 nausea vomiting was observed in 4 patients (10.3%) and in 2 patients (5.1%). Hepatic and renal toxicities were mild. No treatment-related death occurred during this study.

| Adverse event | NCI-CTC grade (n = 39) | Grade 3/4 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Any | ||

| Hematologic | ||||||

| Leucopenia | 15 (25.6) | 13 (33.3) | 4 (10.3) | 2 (5.1) | 34 (87.2) | 15.4% |

| Anemia | 17 (43.6) | 5 (12.8) | 2 (5.1) | 1 (2.6) | 25 (64.1) | 7.7% |

| Thrombocytopenia | 11 (28.2) | 5 (12.8) | 2 (5.1) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (46.2) | 5.1% |

| Nonhematologic | ||||||

| Gastrointestinal | ||||||

| Nausea | 11 (28.2) | 8 (20.5) | 4 (10.3) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (59.0) | 10.3% |

| Vomiting | 10 (25.6) | 6 (15.4) | 2 (5.1) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (46.2) | 5.1% |

| Diarrhea | 6 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (15.4) | 0.0% |

| Stomatitis | 2 (5.1) | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.7) | 0.0% |

| Hepatic | ||||||

| AST | 2 (5.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.1) | 0.0% |

| ALT | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | 0.0% |

| Renal | ||||||

| Serum creatine | 2 (5.1) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.1) | 0.0% |

| Alopecia | 3 (7.7) | 9 (23.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (30.8) | 0.0% |

| Myalgia | 12 (30.8) | 5 (12.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (43.6) | 0.0% |

| Fatigue | 20 (51.3) | 2 (5.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 22 (56.4) | 0.0% |

| Neutropenia fever | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | 2.6% |

Esophageal cancer has two main pathological forms: squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and adenocarcinoma. Because cardiac adenocarcinoma has been usually classified as gastric cancer, primary esophageal adenocarcinoma represents only < 1% of esophageal cancer patients in China[26]. In view of most cases being ESCC, we focused on this type of esophageal cancer in our study. Recurrent or metastatic ESCC remains incurable disease. Systematic combined chemotherapy has been part of combined modality therapy as a palliative treatment for this patient population.

However, there is no standard chemotherapy regimen for advanced esophageal cancer, various kinds of chemotherapy regimens have been tried to prolong survival and improve quality of life. The most commonly used regimen as the first-line chemotherapy is the combination of cisplatin (100 mg/m2 per day) and 5-FU (1000 mg/m2 per day continuous infusion for 96-120 h) in metastatic esophageal cancer[27]. The randomized phase II study comparing cisplatin/5-FU to cisplatin alone in advanced squamous cell esophageal cancer demonstrated that the combination arm was superior to cisplatin alone arm in terms of RR (35% vs 19%, respectively), and OS (33 wk vs 28 wk, respectively)[6]. However, high rate of treatment-related deaths (16%) was not acceptable. What’s more, continuous infusion of 5-FU requires an indwelling venous access, which provides a source for venous thrombosis and sepsis and makes therapy burdensome to the patient. Until recently, newer agents such as taxanes (paclitaxel and docetaxel), vinorelbine, irinotecan, capecitabine, oxaliplatin and nedaplatin have been investigated as single agent or in combination in neoadjuvant or palliative settings[28].

In the current study, the overall RR was 46.2% (50.0% for 36 valuable patients), the disease control rate was 84.6% with a median TTP of 7.1 mo and a median OS of 12.4 mo. This study shows that this regimen has encouraging antitumor activity. Recently, several phase II studies were published of paclitaxel and platinum based regimens for advanced or metastatic esophageal cancer[5,8,9,11,12]. Gong et al[5] reported that the overall RR was 43.6% and the median progression-free survival (PFS) and OS was 6 and 10 mo, respectively, in a phase II study with metastatic esophageal cancer treated with the same combination regimen. Polee et al[11] reported that paclitaxel and cisplatin induced a relative longer median PFS of 8 mo, but the median time of OS was only 9 mo. The highest median OS (13 mo) was reported with 7 mo of median TTP by Zhang et al[12]. The results of our study can be consistent with those of these published studies.

In consideration of the performance status and chemotherapy tolerance of cancer patients in metastatic setting, treatment related toxicities should be strictly limited. In the present study, the most common grade 3/4 toxicities were leucopenia (15.4%), nausea (10.3%) and anemia (7.7%), thromocytopenia (5.1%), vomiting (5.1%), respectively. Only one patient with febrile neutropenia was discontinued from the study, who was successfully treated with antibiotics and G-CSF. There was no treatment-related death during this study. The toxicities of nedaplatin and paclitaxel regimen were similar with the paclitaxel based regimen reported by Zhang et al[12] and Ilson et al[10], and more minimal than other studies which applied gemcitabine plus cisplatin, paclitaxel plus carboplatin, nedaplatin plus docetaxel, or irinotecan plus cisplatin/cisplatin-5-FU[9,29-33]. The combination of nedaplatin and paclitaxel was deemed safe in patients with metastatic esophageal carcinoma in spite of the observed toxicity.

So far, some drugs have been applied for advanced esophageal carcinoma, such as capecitabine and oxaliplatin. More recently, a randomized phase III trial evaluated capecitabine and oxaliplatin as alternatives to infused 5-FU and cisplatin, respectively, for untreated advanced esophagogastric carcinoma[34]. The more active regimen including epirubicin, oxaliplatin and capecitabine achieved the median PFS of 7 mo and median OS of 11.2 mo, while the relative higher treatment-related toxicities were reported. Of note, all the patients in that study were pathologically confirmed adenocarcinama. So, the standard chemotherapy for advanced or metastatic ESCC still needs more clinical trials.

In conclusion, the results from our phase II study demonstrated that the combination of nedaplatin and paclitaxel is active and well tolerated as a first-line therapy for patients with recurrent or metastatic ESCC. It provides recurrent or metastatic ESCC patients with an effective, safe and convenient chemotherapeutic strategy.

The authors are grateful to all the patients and all the staff at the study centers who contributed to this study.

Esophageal cancers are among the most aggressive tumors with a poor prognosis. Till now, there has been no standard chemotherapy regimen for advanced esophageal cancer. In this paper, the author conducted a phase II study on combination chemotherapy consisting of paclitaxel and nedaplatin in previously untreated patients with metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC).

The most commonly used regimen as the first-line chemotherapy is the combination of cisplatin (100 mg/m2 per day) and 5-fluorouracil (1000 mg/m2 per day continuous infusion for 96-120 h) in metastatic esophageal cancer. However, high rate of treatment-related deaths (16%) was not acceptable. So, new regimens were explored to improve the efficacy and safety in metastatic ESCC.

The results demonstrated that the combination of nedaplatin and paclitaxel is active and well tolerated as a first-line therapy for patients with recurrent or metastatic ESCC. It provides recurrent or metastatic ESCC patients with an effective, safe and convenient chemotherapeutic strategy.

The combination of paclitaxel and nedaplatin is active and well tolerated as a first-line therapy for patients with metastatic ESCC.

Paclitaxel, a natural product isolated from the bark of the yew tree Taxus brevifolia, has demonstrated some promising responses against digestive tract cancer. And nedaplatin is a new platinum derivative, selected from a series of platinum analogues based on its pronounced preclinical antitumor activity against various solid tumors with lower nephrotoxicity.

This is a good clinical study in which the authors evaluated the efficacy and safety of paclitaxel-nedaplatin combination as a front-line regimen in Chinese patients with metastatic ESCC. The results are interesting and suggest that the combination of the above two drugs is active and well tolerated as a first-line therapy for patients with metastatic ESCC.

P- Reviewer Kaneko K S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor A E- Editor Ma S

| 1. | Hofstetter W, Swisher SG, Correa AM, Hess K, Putnam JB, Ajani JA, Dolormente M, Francisco R, Komaki RR, Lara A. Treatment outcomes of resected esophageal cancer. Ann Surg. 2002;236:376-384; discussion 384-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vestermark LW, Sørensen P, Pfeiffer P. [Chemotherapy to patients with metastatic carcinoma of the esophagus and gastro-esophageal junction. A survey of a Cochrane review]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2008;170:633-636. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Ilson DH. Oesophageal cancer: new developments in systemic therapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 2003;29:525-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cao W, Xu C, Lou G, Jiang J, Zhao S, Geng M, Xi W, Li H, Jin Y. A phase II study of paclitaxel and nedaplatin as first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced esophageal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009;39:582-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gong Y, Ren L, Zhou L, Zhu J, Huang M, Zhou X, Wang J, Lu Y, Hou M, Wei Y. Phase II evaluation of nedaplatin and paclitaxel in patients with metastatic esophageal carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;64:327-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bleiberg H, Conroy T, Paillot B, Lacave AJ, Blijham G, Jacob JH, Bedenne L, Namer M, De Besi P, Gay F. Randomised phase II study of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) versus cisplatin alone in advanced squamous cell oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:1216-1220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ajani JA, Ilson DH, Daugherty K, Pazdur R, Lynch PM, Kelsen DP. Activity of taxol in patients with squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1086-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cho SH, Chung IJ, Song SY, Yang DH, Byun JR, Kim YK, Lee JJ, Na KJ, Kim HJ. Bi-weekly chemotherapy of paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with metastatic or recurrent esophageal cancer. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20:618-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | El-Rayes BF, Shields A, Zalupski M, Heilbrun LK, Jain V, Terry D, Ferris A, Philip PA. A phase II study of carboplatin and paclitaxel in esophageal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:960-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ilson DH, Wadleigh RG, Leichman LP, Kelsen DP. Paclitaxel given by a weekly 1-h infusion in advanced esophageal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:898-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Polee MB, Eskens FA, van der Burg ME, Splinter TA, Siersema PD, Tilanus HW, Verweij J, Stoter G, van der Gaast A. Phase II study of bi-weekly administration of paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with advanced oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:669-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang X, Shen L, Li J, Li Y, Li J, Jin M. A phase II trial of paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with advanced squamous-cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Am J Clin Oncol. 2008;31:29-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kameyama Y, Okazaki N, Nakagawa M, Koshida H, Nakamura M, Gemba M. Nephrotoxicity of a new platinum compound, 254-S, evaluated with rat kidney cortical slices. Toxicol Lett. 1990;52:15-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kobayashi H, Takemura Y, Miyachi H, Ogawa T. Antitumor activities of new platinum compounds, DWA2114R, NK121 and 254-S, against human leukemia cells sensitive or resistant to cisplatin. Invest New Drugs. 1991;9:313-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kawai Y, Taniuchi S, Okahara S, Nakamura M, Gemba M. Relationship between cisplatin or nedaplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and renal accumulation. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28:1385-1388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Alberts DS, Fanta PT, Running KL, Adair LP, Garcia DJ, Liu-Stevens R, Salmon SE. In vitro phase II comparison of the cytotoxicity of a novel platinum analog, nedaplatin (254-S), with that of cisplatin and carboplatin against fresh, human ovarian cancers. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1997;39:493-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kurita H, Yamamoto E, Nozaki S, Wada S, Furuta I, Kurashina K. Multicenter phase I trial of induction chemotherapy with docetaxel and nedaplatin for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2004;40:1000-1006. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Taguchi T, Wakui A, Nabeya K, Kurihara M, Isono K, Kakegawa T, Ota K. [A phase II clinical study of cis-diammine glycolato platinum, 254-S, for gastrointestinal cancers. 254-S Gastrointestinal Cancer Study Group]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1992;19:483-488. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Kurata T, Tamura K, Yamamoto N, Nogami T, Satoh T, Kaneda H, Nakagawa K, Fukuoka M. Combination phase I study of nedaplatin and gemcitabine for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2092-2096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Okuda K, Hirose T, Ishida H, Kusumoto S, Sugiyama T, Ando K, Shirai T, Ohnishi T, Horichi N, Ohmori T. Phase I study of the combination of nedaplatin and weekly paclitaxel in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61:829-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Noda K, Ikeda M, Yakushiji M, Nishimura H, Terashima Y, Sasaki H, Hata T, Kuramoto H, Tanaka K, Takahashi T. [A phase II clinical study of cis-diammine glycolato platinum, 254-S, for cervical cancer of the uterus]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1992;19:885-892. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Sekine I, Nokihara H, Horiike A, Yamamoto N, Kunitoh H, Ohe Y, Tamura T, Kodama T, Saijo N. Phase I study of cisplatin analogue nedaplatin (254-S) and paclitaxel in patients with unresectable squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1125-1128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tanaka R, Takii Y, Shibata Y, Ariyama H, Qin B, Baba E, Kusaba H, Mitsugi K, Harada M, Nakano S. In vitro sequence-dependent interaction between nedaplatin and paclitaxel in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2005;56:279-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yamada H, Uchida N, Maekawa R, Yoshioka T. Sequence-dependent antitumor efficacy of combination chemotherapy with nedaplatin, a newly developed platinum, and paclitaxel. Cancer Lett. 2001;172:17-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Simon R. Optimal two-stage designs for phase II clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2789] [Cited by in RCA: 2941] [Article Influence: 81.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bai SX. Primary esophageal adenocarcinoma--report of 19 cases. Zhonghua Zhongliu Zazhi. 1989;11:383-385. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Devita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors . Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins 2005; . |

| 28. | Lee J, Im YH, Cho EY, Hong YS, Lee HR, Kim HS, Kim MJ, Kim K, Kang WK, Park K. A phase II study of capecitabine and cisplatin (XP) as first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;62:77-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ilson DH, Ajani J, Bhalla K, Forastiere A, Huang Y, Patel P, Martin L, Donegan J, Pazdur R, Reed C. Phase II trial of paclitaxel, fluorouracil, and cisplatin in patients with advanced carcinoma of the esophagus. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1826-1834. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Ilson DH, Saltz L, Enzinger P, Huang Y, Kornblith A, Gollub M, O’Reilly E, Schwartz G, DeGroff J, Gonzalez G. Phase II trial of weekly irinotecan plus cisplatin in advanced esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3270-3275. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Kanai M, Matsumoto S, Nishimura T, Shimada Y, Watanabe G, Kitano T, Misawa A, Ishiguro H, Yoshikawa K, Yanagihara K. Retrospective analysis of 27 consecutive patients treated with docetaxel/nedaplatin combination therapy as a second-line regimen for advanced esophageal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2007;12:224-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Millar J, Scullin P, Morrison A, McClory B, Wall L, Cameron D, Philips H, Price A, Dunlop D, Eatock M. Phase II study of gemcitabine and cisplatin in locally advanced/metastatic oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1112-1116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Urba SG, Chansky K, VanVeldhuizen PJ, Pluenneke RE, Benedetti JK, Macdonald JS, Abbruzzese JL. Gemcitabine and cisplatin for patients with metastatic or recurrent esophageal carcinoma: a Southwest Oncology Group Study. Invest New Drugs. 2004;22:91-97. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Cunningham D, Starling N, Rao S, Iveson T, Nicolson M, Coxon F, Middleton G, Daniel F, Oates J, Norman AR. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced esophagogastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:36-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1579] [Cited by in RCA: 1689] [Article Influence: 99.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |