Published online Jun 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i22.3524

Revised: April 29, 2013

Accepted: May 22, 2013

Published online: June 14, 2013

Processing time: 155 Days and 12.1 Hours

Hepatoid carcinoma is a unique type of extrahepatic tumor associated with hepatic differentiation and displays the morphological and functional features of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatoid carcinoma of the extrahepatic duct has rarely been reported in the literature. We report a 62-year-old man who presented with epigastric discomfort, xanthochromia, dull pain of the right shoulder, nausea and pruitus. Microscopic examination of the extrahepatic duct indicated that the tumor was primarily composed of “hepatoid cells”, which were characterized by an eosinophilic cytoplasm, enlarged nucleus and prominent nucleoli. The cells were arranged in nests or proliferated in a trabecular pattern. Immunohistochemistry indicated that the tumor cells were positive for hepatocyte paraffin 1 and cytokeratins 8 and 18. Based on these findings, this case was diagnosed as hepatoid carcinoma of the extrahepatic duct.

Core tip: Hepatoid adenocarcinoma (HAC) is a rare type of extrahepatic adenocarcinoma that resembles hepatocellular carcinoma. Although the stomach is the most common location for this tumor, the lung, pancreas, esophagus, papilla of Vater, colon, urinary bladder, renal pelvis, ovaries, uterus and cervix have also been reported as primary locations. To the best of our knowledge, HAC arising primarily from the extrahepatic duct has not previously been reported in the literature. This report presents a rare case of HAC of the hepatic duct and performs a differential diagnosis based on immunochemical results, detailed clinical history and endoscopic findings.

- Citation: Wang Y, Liu YY, Han GP. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the extrahepatic duct. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(22): 3524-3527

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i22/3524.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i22.3524

Hepatoid adenocarcinoma (HAC) of the stomach was first described by Ishikura et al in 1985. Carcinomas with hepatoid differentiation have since been described in a variety of locations, including the lung, kidney, female reproductive tract, pancreas, gallbladder and stomach (the most prevalent site)[1-6]. An adenocarcinoma of the papilla of Vater showing hepatoid differentiation has previously been reported[2]. This tumor was proposed to be a specific type of carcinoma of the Vater. HAC is characterized by hepatic differentiation, which is determined based on both morphological and functional features[7].

To the best of our knowledge, cases of HAC of the extrahepatic duct have not previously been reported. Herein, we present a rare case of HAC of the hepatic duct, which may be proposed as a new site of this carcinoma.

A 62-year-old man presented with epigastric discomfort, xanthochromia, dull pain of the right shoulder, nausea and pruritus. A physical examination identified edema in both lower extremities and his feet. Epigastric tenderness to deep palpation was present but rebound tenderness was undetected. Muscular tension was negative. The liver and spleen were unreachable under the ribs. The hepatojugular reflux was negative. The patient denied any history of infection. Caput medusae, spider angioma and palmar erythema were not ovserved. Bowle sounds were detected twice per minute. Hepatitis B surface antigen (HbsAg) and hepatitis C-antibody were negative. Cholecystectomy, laparoscopic common bile duct exploration and cholangio-enterostomy were performed.

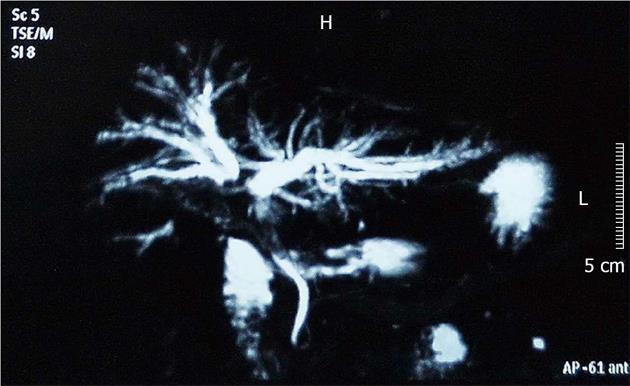

Abdominal ultrasonography revealed hepatic adipose infiltration, intrahepatic cholangiectasis, and choledochectasia. The above description included the possibility of upper hepatic duct obstruction. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) demonstrated that the branches of the intrahepatic bile duct, the ductus hepaticus sinister and the ductus hepaticus dexter flowed normally. Intrahepatic cholangiectasis and aclasis of the ductus hepaticus sinister and the ductus hepaticus dexter were observed (Figure 1). The common hepatic duct, gall bladder and upper segment of the common bile duct could not be visualized. The imaging suggested obstructive jaundice of the upper segment of the bile duct. The obstruction was observed in the proximity of the hepatic portal area, and a lesion occupying the hepatic portal area was considered.

During the exploratory laparotomy, a small degree of abdominal dropsy and intrahepatic cholestasis were observed. The spleen was normal and the gallbladder wall was thickened. Foci of severe inflammation adhered to surrounding tissues were detected and the wall of the common bile duct was thickened and the lumen dilated (diameter of 3 cm). A solid space-occupying lump could be felt within the ampulla of the common bile duct. Therefore, cholecystectomy, laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct and a cholangioenterostomy were performed. Intraoperative consultation reported a small number of malignant cells in the necrotic tissues, however, the origin of the cells could not be confirmed. A repeated search for the origin of the cells failed to identify a primary lesion in the liver, gastrointestinal tract or pancreas. A choledochojejunostomy was subsequently performed.

A gross examination revealed a purple and red solid mass in the hepatic duct corresponding to the occupying lesion observed by MRCP, measuring 1.5 × 1.2 × 1.0 cm3. In addition, one tubular mass in the common hepatic duct (1 cm in diameter and 0.2 cm in depth), one tubular mass in the ductus hepaticus sinister (1.0 × 0.6 × 0.2 cm3), one gray and yellow solid mass in the ductus hepaticus dexter (1.2 × 1.2 × 0.5 cm3), a mass of fragmented red and purple contents in the hepatic duct (3.5 × 3.0 × 0.4 cm3), one gallbladder containing bile (4 cm in diameter and 9 cm in length), and two lymph nodes attached to the mesentery were also observed.

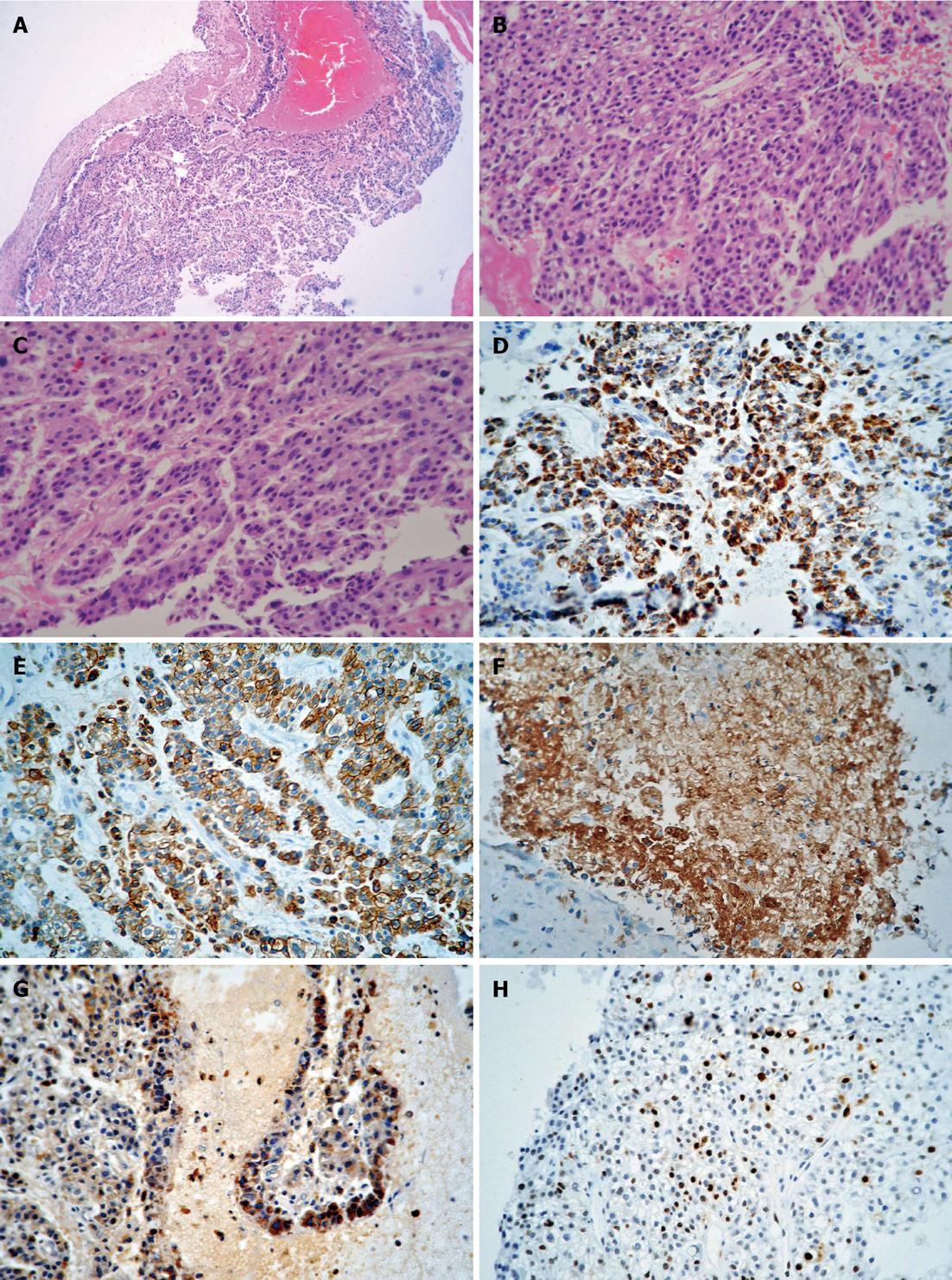

Microscopically, the tumor was primarily composed of “hepatoid cells”, which were characterized by an eosinophilic cytoplasm, enlarged nucleus, and prominent nucleoli. The tumor cells were arranged in nests or proliferated in a trabecular pattern. The tumor consisted of marginal areas of dysplastic glands and well-differentiated intestinal-type adenocarcinomatous tissue, which formed the bulk of the tumor (Figure 2A-C). None of the lymph nodes dissected at surgery showed tumor metastasis. Immunohistochemistry indicated that the tumor cells were positive for hepatocyte paraffin 1 (HepPar-1), cytokeratins 8 and 18 (CK8/18), polyclonal carcinoembryonic antigen (pCEA) and S-100 (Figure 2D-G). Approximately 15% of the tumor cells were positive for Ki-67 (Figure 2H).

Based on the above findings, the case was diagnosed as HAC of the hepatic duct was made.

HAC a rare variant of extrahepatic adenocarcinoma, consists of foci of both adenomatous and hepatocellular differentiation that behave morphologically and functionally similar to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[8,9]. As previously mentioned, the primary characteristics of HAC are histopathological features that suggest hepatoid differentiation resembling HCC. The tumor is generally composed of large or polygonal cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and proliferates in a solid or trabecular pattern, although medullary proliferation is occasionally observed[10]. The hepatoid nature of the cells can be proven based on the detection of bile production[1]. Primary gastric HAC has been the most frequently analyzed type of HAC. Glandular and hepatocyte differentiation both have been obserned and the explanation for this phenomenon is “enteroblastic differentiation”. Because the stomach and liver are derived from the primordial foregut, prosoplasis that occurs during the maturation of the cells may induce the formation described above.

Clear cell carcinomas of the gallbladder with or without hepatoid differentiation are often associated with high serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) levels[10], however, not all HACs are associated with AFP overproduction[11]. In the present case, the preoperative serum AFP level was 6.84 μg/L, and immunohistochemistry suggested that AFP protein was not expressed. However, focal positivity for HepPar-1 suggested the presence of hepatoid differentiation, and pCEA positivity indicated canalicular differentiation and hepatocellular origin. CK8/18 expression in this case resembled HCC and could also be considered to be as a marker of hepatocellular origin.

HCC generally arises in cirrhotic livers and with hepatitis virus infection, however, the preoperative examination revealed that this patient was negative for HBsAg. In the present case, the rough region of the ductus hepaticus sinister was observed by the operator during laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct. Combined with the clinical findings, the extrahepatic ductal origin of the HAC was verified by the clinical presentation, its morphological similarity to HCC, the immunohistochemical identification of liver-synthesized proteins, and bile production[2].

The differential diagnosis of HAC and HCC with invasion into the hepatic duct is primarily dependent upon tumor location. No primary lesion was identified in the liver, gastrointestinal tract or pancreas during surgery. In addition, MRCP and computed tomography angiography (not shown) did not reveal lumps in the liver. The literature has shown that HAC is generally found in elderly males, and poor outcomes are observed. The pathological findings in immunohistochemical analyses may also aid in the differential diagnosis of HAC from HCC: an evaluation using a panel of immunohistochemical markers (e.g., cytokeratin 19, palate, lung and nasal epithelium clone, HepPar-1 and carcinoembryonic antigen), combined with detailed clinical history and endoscopic findings is essential for a definitive diagnosis.

P- Reviewer Sheng Z S- Editor Huang XZ L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Gakiopoulou H, Givalos N, Liapis G, Agrogiannis G, Patsouris E, Delladetsima I. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:3358-3362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gardiner GW, Lajoie G, Keith R. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the papilla of Vater. Histopathology. 1992;20:541-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kwon JE, Kim SH, Cho NH. No ancillary finding is valid to distinguish a primary ovarian hepatoid carcinoma from metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:1691-1694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Takeuchi K, Kitazawa S, Hamanishi S, Inagaki M, Murata K. A case of alpha-fetoprotein-producing adenocarcinoma of the endometrium with a hepatoid component as a potential source for alpha-fetoprotein in a postmenopausal woman. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:1442-1445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Thamboo TP, Wee A. Hep Par 1 expression in carcinoma of the cervix: implications for diagnosis and prognosis. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:48-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kitamura H, Ikeda K, Honda T, Ogino T, Nakase H, Chiba T. Diffuse hepatoid adenocarcinoma in the peritoneal cavity. Intern Med. 2006;45:1087-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Supriatna Y, Kishimoto T, Uno T, Nagai Y, Ishikura H. Evidence for hepatocellular differentiation in alpha-fetoprotein-negative gastric adenocarcinoma with hepatoid morphology: a study with in situ hybridisation for albumin mRNA. Pathology. 2005;37:211-215. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Sakamoto K, Monobe Y, Kouno M, Moriya T, Sasano H. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder: Case report and review of the literature. Pathol Int. 2004;54:52-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhang S, Wang M, Xue YH, Chen YP. Cerebral metastasis from hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the stomach. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5787-5793. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Vardaman C, Albores-Saavedra J. Clear cell carcinomas of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:91-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nakashima H, Nagafuchi K, Satoh H, Takeda K, Yamasaki T, Yonemasu H, Kishikawa H. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2000;7:226-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |