Published online Apr 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i16.2555

Revised: March 26, 2013

Accepted: March 28, 2013

Published online: April 28, 2013

Processing time: 115 Days and 17.7 Hours

AIM: To assess the therapeutic value of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) under micro-probe ultrasound guidance for rectal carcinoids less than 1 cm in diameter.

METHODS: Twenty-one patients pathologically diagnosed with rectal carcinoids following colonoscopy in our hospital from January 2007 to November 2012 were included in this study. The patients consisted of 14 men and 7 women, with a mean age of 52.3 ± 12.2 years (range: 36-72 years). The patients with submucosal tumors less than 1 cm in diameter arising from the rectal and muscularis mucosa detected by micro-probe ultrasound were treated with EMR and followed up with conventional endoscopy and micro-probe ultrasound.

RESULTS: All of the 21 tumors were confirmed by micro-probe ultrasound as uniform hypoechoic masses originating from the rectal and muscularis mucosa, without invasion of muscularis propria and vessels, and less than 1 cm in diameter. EMR was successfully completed without bleeding, perforation or other complications. The resected specimens were immunohistochemically confirmed to be carcinoids. Patients were followed up for one to two years, and no tumor recurrence was reported.

CONCLUSION: EMR is a safe and effective treatment for rectal carcinoids less than 1 cm in diameter.

Core tip: Rectal carcinoids are rare neuroendocrine tumors that are often missed or misdiagnosed in clinical settings due to the absence of specific symptoms in the early stage. This study reports on a hospital-based series of 21 patients who were successfully treated and followed up for 1-2 years for small rectal carcinoids less than 1 cm by means of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) under micro-probe ultrasound guidance. EMR is found to be a safer option with fewer complications, shorter operation time, and comparable rate of complete removal to endoscopic submucosal dissection, therefore, EMR is more suitable for treating rectal carcinoids less than 1 cm in diameter.

- Citation: Zhou FR, Huang LY, Wu CR. Endoscopic mucosal resection for rectal carcinoids under micro-probe ultrasound guidance. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(16): 2555-2559

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i16/2555.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i16.2555

Rectal carcinoids are rare neuroendocrine tumors that are often missed or misdiagnosed in clinical settings due to the absence of specific symptoms in the early stage[1]. With the widespread popularity of colonoscopy, however, the detection rate of rectal carcinoids has been increasing in recent years, enabling us to achieve better outcomes for patients with submucosal tumors (SMTs) derived from the muscular layer of rectal mucosa using endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) combined with micro-probe ultrasound examination. The following is a summary of a retrospective analysis of 21 patients with pathologically confirmed rectal carcinoid tumors treated in our hospital from January 2007 to November 2012.

Twenty-one patients pathologically diagnosed with rectal carcinoids following colonoscopy in our hospital from January 2007 to November 2012 were included in this study. The patients consisted of 14 men and 7 women, with a mean age of 52.3 ± 12.2 years (range: 36-72 years).

Equipment: Olympus GIF-260 Endoscope, Fujinon-Sp702 micro-probe system, with a micro-probe frequency of 20 mHz and probe diameter of 2.5 mm.

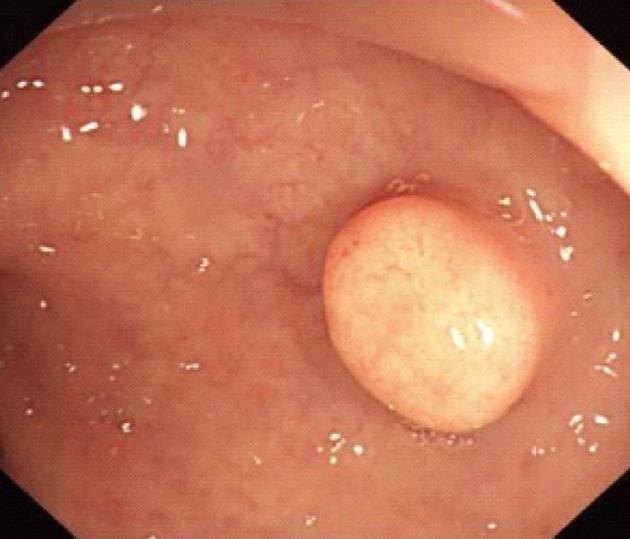

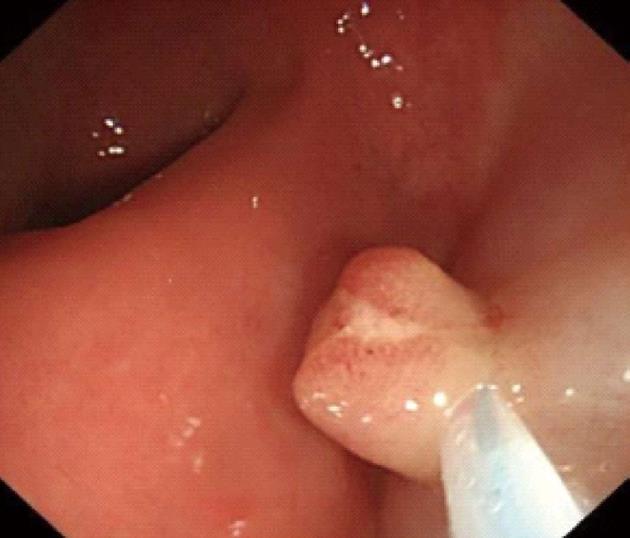

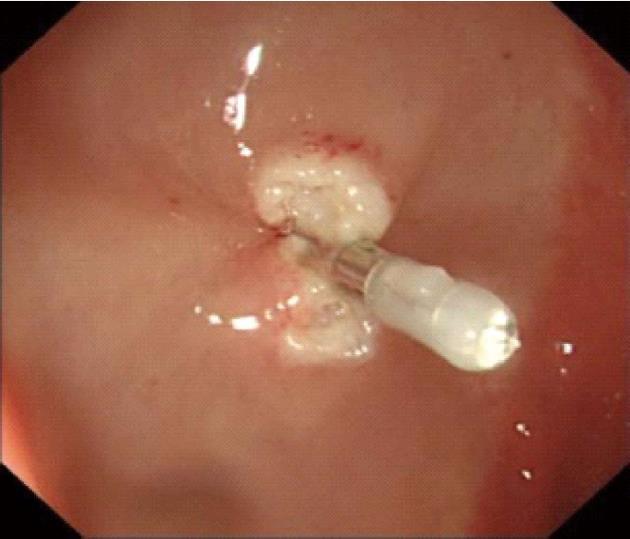

Procedures: Lesions were assessed by endoscopic ultrasonography (Figures 1-7), and endoscopic submucosal resection was performed for lesions less than 1 cm in diameter and not deeper than the submucosa. Normal saline was injected into the root of each tumor under colonoscopy to form a bulge before EMR. Metal hemoclipping was applied to the excision wounds to prevent postoperative perforation, bleeding and other complications. The removed tissues were sent for pathological identification. All specimens were fixed with 10% formalin, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin for immunohistochemistry in the Department of Pathology.

Colonoscopy was performed for subjects with unexplained changes in bowel habit (including stool frequency and consistency) and those who underwent routine physical examinations, and 21 patients were diagnosed as having rectal carcinoids. Among the 21 cases of rectal carcinoids, 16 (76.2%) cases were located within 8 cm and 5 (23.8%) cases were located within 8-10 cm from the anal margin. The typical submucosal lesions with smooth mucosal surface were the predominant endoscopic manifestations (85.7%, 18/21). Three (14.31%, 3/21) lesions were depressed and erosive at the top region, and 17 (80.9%, 17/21) appeared tough or hard, and only 1 lesion was soft (0.5%). Seventeen (80.9%) cases appeared yellow, and 4 (19.1%) cases appeared red or normal.

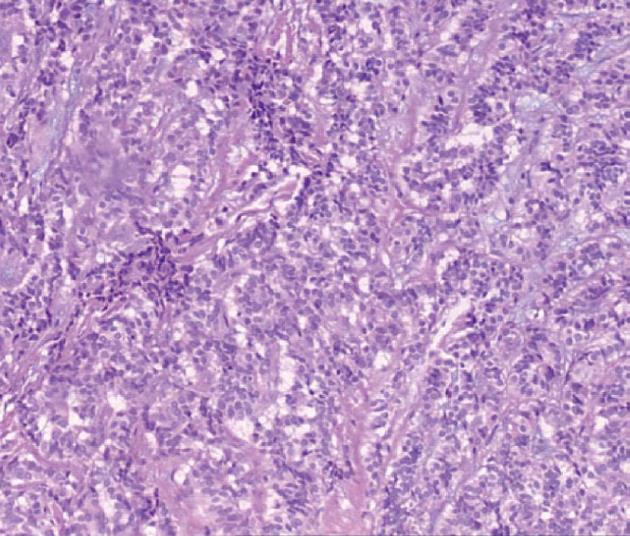

All of the 21 tumors were confirmed by micro-probe ultrasound as uniform hypoechoic masses originating from the rectal and muscularis mucosa, without invasion of muscularis propria and vessels, and less than 1 cm in diameter. EMR was successfully completed without bleeding, perforation or other complications. The resected specimens were immunohistochemically diagnosed as carcinoids. The post-operative follow-up lasted 1-2 years, during which colonoscopy was performed in the first month, and then in months 3, 6, 12 and 24. No tumor relapse was noted.

Carcinoid tumors are derived from argyrophilic cells in the intestinal glandular base (Kulchitsky cells) and are known for their affinity for silver staining, thus, these tumors are also known as argyrophil cell carcinomas. Rare as they are, carcinoids can occur in multiple body systems, with the gastrointestinal tract being the most commonly involved system. Rectal carcinoids are the third leading gastrointestinal carcinoids, accounting for about 14% of all conditions of this type[1], with an increasing incidence in recent years potentially attributable to extensive endoscopic application and increased awareness of carcinoid tumors. Epidemiological surveys have revealed that the incidence rate of gastrointestinal carcinoids has increased year by year with the popularity of endoscopy, and ranges from 0.27 to 1.33 per 100000 people. The highest incidence was found in the appendix (38%), followed by the small intestine (29%), colon (13%), and stomach (12%). Based on the epidemiological statistics in Europe and North America conducted by Shields et al[2], the median age for rectal carcinoids is 55 years, the average tumor size is 10 mm, and the average age of onset for the surveyed patients is 52 years, similar to the findings in this study.

Accounting for about 1.33% of rectal tumors, rectal carcinoids can give rise to non-specific symptoms such as general discomfort, constipation, blood in stool, abdominal pain, weight loss, and change in bowel habits[3]. Based on their origins, carcinoids can be divided into foregut, midgut and hindgut tumors. Rectal carcinoids, originating in the hindgut, generally secrete no or few active substances, such as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), resulting in normal 5-HT and 24 h 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid levels and a very low risk of carcinoid syndromes in patients[4].

Colonoscopy is an important tool in the detection of rectal carcinoids. Typical manifestations include single or multiple yellow or gray submucosal nodular masses covered with normal mucosa. Atypical carcinoids are often associated with irregular, hard ulcers. Endoscopic ultrasonography has become a necessary part of the diagnosis of rectal carcinoids and helps to determine the size, origin, contour, borders and depth of submucosal invasion, which are important for the differential diagnosis. Carcinoid lesions mostly originate in the submucosa or muscularis mucosa, and have a hypoechoic appearance. In addition, pathological examination is an important means of diagnosing rectal carcinoids. Typical histology includes solid nesting, nodular, insular, trabecular, palisading and rosette-like patterns, with small oval or polygonal, nested or glandular-like carcinoid cells, a regular and small nucleus, and little or no mitotic figures under the microscope. Chromogranin A, neuron-specific enolase and synaptophysin are the most sensitive and specific markers of neuroendocrine cells[5].

Studies have shown that lymph node metastasis and liver metastasis of a given rectal carcinoid are significantly correlated with the size of the tumor. The incidence rates of lymph node metastasis are 3%, 7% and 64% for rectal carcinoids < 1 cm, 1-2 cm and > 2 cm in diameter, respectively. Therefore, it is generally believed that metastasis is rare in rectal carcinoids less than 1 cm, but more often seen in those > 2 cm[6]. Carcinoid metastasis occurs by direct invasion, including invasion of the surrounding tissue by serosal penetration, while lymph node metastasis or hematogenous metastasis can also be observed.

It is generally accepted that lymphatic invasion, muscularis propria invasion and lymph node metastasis are unlikely to occur in rectal carcinoid tumors < 1 cm in diameter and such small, well differentiated tumors can be removed endoscopically or by local excision. Endoscopic ultrasound must be employed to determine the exact size and depth of invasion of the tumor before surgery. The absence of preoperative staging will result in a suspicious or even positive pathological resection margin in 31.8%-83% of patients[7,8]. In contrast, appropriate endoscopic ultrasound staging before endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) reduces the postoperative positive margin rate to between 4.8% and 17%[9]. Therefore, this technique should be routinely performed before local excision of rectal carcinoids. Traditionally, most rectal carcinoid tumors of 1 cm or smaller are treated with EMR.

With the development of endoscopic techniques, many clinicians have been using ESD for the local resection of these tumors. Compared with traditional EMR, en bloc removal can be achieved using ESD regardless of tumor size, but it is also associated with a higher risk of complications (such as intraoperative or postoperative bleeding and perforation) and longer duration of operation. Yamaguchi et al[10] reported complete removal in 90% of their 20 patients with rectal carcinoids of < 1 cm using ESD, with an average operation time of 45 min, and one case of perforation. As reported by Lee et al[11], complete removal was achieved in 89.3% and 100% of patients undergoing EMR and ESD, without a significant difference in the size of tumors, respectively. EMR was successfully completed in all 21 patients with a rectal carcinoid of less than 1 cm in diameter without bleeding, perforation or other complications. The mean operation time was 15 min. The operation duration in the ESD group was significantly longer compared with the EMR group. It can be seen that, for lesions less than 1 cm in diameter, there is no considerable difference in the rate of complete removal between the EMR and ESD techniques, although a higher risk of complications and longer operation are associated with the latter technique.

For regional lymph node-negative patients with rectal carcinoids < 1 cm without muscular and vascular invasion, the 5-year survival rate can be 98.9% to 100% after treatment. Those who have positive lymph nodes but no distant metastases have a 5-year survival rate of 54% to 73%, and those with metastases have a 5-year survival rate of approximately 15%-30%[12]. Wang et al[13] found that the presence or absence of muscularis propria infiltration is the only determining factor in the 5-year survival rate, which is closely related to tumor size. Yoon et al[14] reported that, the possibility of distant metastasis from rectal carcinoids increases with tumor volume and T staging, as well as the presence of lymphatic, vascular or neural invasion. EMR was performed for the 21 patients with a rectal carcinoid of less than 1 cm in diameter. Pre-operative micro-probe ultrasound showed homogeneous hypoechoic masses derived from rectal mucosa and/or muscularis mucosa, but without infiltration in the muscularis propria or blood vessels. The tumor was completely removed. The resected specimens were immunohistochemically diagnosed as carcinoids. No relapse was noted during the follow-up of 1-2 years. The resection rate was high in our cohort and no relapse was noted, which may be explained by the small sample size and short follow-up. Therefore, studies with larger sample size and longer follow-up are warranted.

Although rectal carcinoid tumors are potentially malignant, they often grow slowly and present with a fairly long disease course, with favorable outcomes. To sum up, since lymphatic invasion, muscularis propria invasion and lymph node metastasis are unlikely to occur in rectal carcinoid tumors < 1 cm in diameter, these small, well differentiated tumors can be treated by endoscopic resection. A growing number of rectal carcinoids can be detected early with endoscopy, and endoscopic ultrasonography is a necessary part of the diagnosis of rectal carcinoids and can help to determine the size, origin, contour, borders and depth of submucosal invasion, which are important for the differential diagnosis and choice of treatment. EMR and ESD are the primary endoscopic treatments for these conditions, and EMR is a safer option with fewer complications, shorter operating time, and comparable rate of complete removal to ESD. We believe that EMR is more suitable for treating rectal carcinoids less than 1 cm in diameter.

Rectal carcinoids are rare neuroendocrine tumors that are often missed or misdiagnosed in clinical settings due to the absence of specific symptoms in the early stage. Rare as they are, carcinoids can occur in multiple body systems, with the gastrointestinal tract being the most commonly involved system. Rectal carcinoids are the third leading gastrointestinal carcinoids, accounting for about 14% of all conditions of this type, with an increasing incidence in recent years potentially attributable to extensive endoscopic application and increased awareness of carcinoid tumors.

With the development of endoscopic techniques, many clinicians have been using endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for the local resection of these tumors. Compared with traditional endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), en bloc removal can be achieved using ESD regardless of tumor size, but it is also associated with a higher risk of complications (such as intraoperative or postoperative bleeding and perforation) and longer duration of operation.

A growing number of rectal carcinoids can be detected early with endoscopy, and endoscopic ultrasonography is a necessary part of the diagnosis of rectal carcinoids and can help to determine the size, origin, contour, borders and depth of submucosal invasion, which are important for the differential diagnosis and choice of treatment. EMR and ESD are the primary endoscopic treatments for these conditions, and EMR is a safer option with fewer complications, shorter operation time, and comparable rate of complete removal to ESD. The authors believed that EMR is more suitable for treating rectal carcinoids less than 1 cm in diameter.

The authors evaluated the role of EMR under micro-probe ultrasound guidance in treatment of rectal carcinoids, and concluded that EMR is a safe and effective treatment for rectal carcinoids less than 1 cm in diameter.

ESD is an advanced technique of therapeutic endoscopy for superficial gastrointestinal neoplasms. EMR represents a major advance in minimally invasive surgery in the gastrointestinal tract. EMR is based on the concept that endoscopy provides visualization and access to the mucosa, the innermost lining of the gastrointestinal tract.

This is a retrospective case series of endoscopic removal of rectal carcinoid smaller than 1 cm. The authors evaluated the role of EMR under micro-probe ultrasound guidance in treatment of rectal carcinoids, and concluded that EMR is a safe and effective treatment for rectal carcinoids less than 1 cm in diameter. The paper is well organized and correctly reported. Some issues are needed to be concerned.

P- Reviewers Dehghani SM, Gruttadauria S, Luzza F S- Editor Huang XZ L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Modlin IM, Kidd M, Latich I, Zikusoka MN, Shapiro MD. Current status of gastrointestinal carcinoids. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1717-1751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 565] [Cited by in RCA: 524] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Shields CJ, Tiret E, Winter DC. Carcinoid tumors of the rectum: a multi-institutional international collaboration. Ann Surg. 2010;252:750-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dallal HJ, Ravindran R, King PM, Phull PS. Gastric carcinoid tumour as a cause of severe upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Endoscopy. 2003;35:716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Toth-Fejel S, Pommier RF. Relationships among delay of diagnosis, extent of disease, and survival in patients with abdominal carcinoid tumors. Am J Surg. 2004;187:575-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Schnirer II, Yao JC, Ajani JA. Carcinoid--a comprehensive review. Acta Oncol. 2003;42:672-692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Läuffer JM, Zhang T, Modlin IM. Review article: current status of gastrointestinal carcinoids. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:271-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kwaan MR, Goldberg JE, Bleday R. Rectal carcinoid tumors: review of results after endoscopic and surgical therapy. Arch Surg. 2008;143:471-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kim YJ, Lee SK, Cheon JH, Kim TI, Lee YC, Kim WH, Chung JB, Yi SW, Park S. [Efficacy of endoscopic resection for small rectal carcinoid: a retrospective study]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2008;51:174-180. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Mashimo Y, Matsuda T, Uraoka T, Saito Y, Sano Y, Fu K, Kozu T, Ono A, Fujii T, Saito D. Endoscopic submucosal resection with a ligation device is an effective and safe treatment for carcinoid tumors in the lower rectum. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:218-221. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Yamaguchi N, Isomoto H, Nishiyama H, Fukuda E, Ishii H, Nakamura T, Ohnita K, Hayashi T, Kohno S, Nakao K. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for rectal carcinoid tumors. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:504-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lee DS, Jeon SW, Park SY, Jung MK, Cho CM, Tak WY, Kweon YO, Kim SK. The feasibility of endoscopic submucosal dissection for rectal carcinoid tumors: comparison with endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2010;42:647-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Konishi T, Watanabe T, Kishimoto J, Kotake K, Muto T, Nagawa H. Prognosis and risk factors of metastasis in colorectal carcinoids: results of a nationwide registry over 15 years. Gut. 2007;56:863-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang M, Peng J, Yang W, Chen W, Mo S, Cai S. Prognostic analysis for carcinoid tumours of the rectum: a single institutional analysis of 106 patients. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:150-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yoon SN, Yu CS, Shin US, Kim CW, Lim SB, Kim JC. Clinicopathological characteristics of rectal carcinoids. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25:1087-1092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |