Published online Apr 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i14.2256

Revised: January 18, 2013

Accepted: February 5, 2013

Published online: April 14, 2013

Processing time: 134 Days and 0.3 Hours

AIM: To investigate whether the disease progression of chronic hepatitis C patients with normal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels differs by ALT levels.

METHODS: A total of 232 chronic hepatitis C patients with normal ALT (< 40 IU/L) were analyzed. The patients were divided into “high-normal” and “low-normal”ALT groups after determining the best predictive cutoff level associated with disease progression for each gender. The incidence of disease progression, as defined by the occurrence of an increase of ≥ 2 points in the Child-Pugh score, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, bleeding gastric or esophageal varices, hepatic encephalopathy, the development of hepatocellular carcinoma, or death related to liver disease, were compared between the two groups.

RESULTS: Baseline serum ALT levels were associated with disease progression for both genders. The best predictive cutoff baseline serum ALT level for disease progression was 26 IU/L in males and 23 IU/L in females. The mean annual disease progression rate was 1.2% and 3.9% for male patients with baseline ALT levels ≤ 25 IU/L (low-normal) and > 26 IU/L (high-normal), respectively (P = 0.043), and it was 1.4% and 4.8% for female patients with baseline ALT levels ≤ 22 IU/L (low-normal) and > 23 IU/L (high-normal), respectively (P = 0.023). ALT levels fluctuated during the follow-up period. During the follow-up, more patients with “high-normal” ALT levels at baseline experienced ALT elevation (> 41 IU/L) than did patients with “low-normal” ALT levels at baseline (47.7% vs 27.9%, P = 0.002). The 5 year cumulative incidence of disease progression was significantly lower in patients with persistently “low-normal” ALT levels than “high-normal” ALT levels or those who exhibited an ALT elevation > 41 U/L during the follow-up period (0%, 8.3% and 34.3%, P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION: A “high normal” ALT level in chronic hepatitis C patients was associated with disease progression, suggesting that the currently accepted normal threshold of serum ALT should be lowered.

Core tip: Recent studies have indicated that the upper limit of normal for the serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level should be lowered. However, outcome studies based on the development of adverse events during long-term follow-up are limited. In this present study, among patients infected with chronic hepatitis C virus who had normal ALT levels, the risk of disease progression differed between patients with “high-normal” and “low-normal” ALT levels, even within the currently accepted normal levels. This finding suggests that lowering the normal threshold of ALT levels may be necessary to better identify patients who are at increased risk for disease progression.

- Citation: Sinn DH, Gwak GY, Shin JU, Choi MS, Lee JH, Koh KC, Paik SW, Yoo BC. Disease progression in chronic hepatitis C patients with normal alanine aminotransferase levels. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(14): 2256-2261

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i14/2256.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i14.2256

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is an easily available, low-cost screening tool for detecting hepatocellular disease[1,2]. Currently, the upper limit of normal (ULN) of ALT has been set at a mean value ± 2SD in a group of healthy individuals[1], usually at approximately 40 IU/L in many hospitals, including our hospital, although this value varies slightly between laboratories. However, several recent studies have demonstrated that the ULN of ALT should be lower than the currently accepted thresholds[3-7]. In these studies, the ULN of ALT was assessed in the standard manner (set at a mean value ± 2SD for healthy individuals); however, by defining a “new” healthy reference population, largely by excluding metabolically abnormal individuals[6]. If the ULN of ALT, often interchangeably used with the healthy level, is defined in this manner, it will vary according to the chosen reference class.

Another way of defining the ULN of ALT, or healthy levels, involves outcome studies, which are based on the development of adverse events during long-term follow-up[8-11]. The ULN of ALT can be set at a level that places individuals at increased risk of adverse consequences. In fact, a “high-normal” ALT level, even within the currently accepted normal range, has been associated with increased liver disease-related mortality[12,13], suggesting that the “healthy” ALT level should be lower than the currently accepted thresholds. In the present study, we aimed to assess whether a “high-normal” ALT level is associated with an increased risk of disease progression among patients with chronic hepatitis C.

Previously, we reported the incidence and risk factors of disease progression in 1137 patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections[14]. The present study is a subgroup analysis of our previous study. In our previous study, we enrolled 1137 chronic hepatitis C patients who had no history or evidence of advanced liver disease. The detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in our previous report[14]. Briefly, patients exhibited evidence of chronic HCV infection but had no history or evidence of cirrhotic complications, including a Child-Pugh score of > 5 points, esophageal or gastric variceal bleeding, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatic encephalopathy, and HCC. For the present study, out of a total of 1137 patients, we selected 232 patients who did not receive antiviral therapy for chronic HCV infection and exhibited normal ALT levels (< 40 IU/L) at enrollment.

Follow-up data collection and endpoint assessment followed the protocol of our previous study[14]. Briefly, all patients were followed-up at least every 3-6 mo, or more frequently as required, for at least 1 year. Follow-up tests included conventional biochemical tests and abdominal ultrasonography screening. Endoscopic examination was performed when patients exhibited any symptoms or signs suggesting gastrointestinal bleeding, such as hematemesis, melena, hematochezia or sudden drops in blood hemoglobin levels. If patients did not exhibit any indications of gastrointestinal bleeding, endoscopic examination was not performed routinely or regularly. Patients who dropped out during the follow-up or who died without reaching the endpoint were classified as either withdrawals or censored cases, respectively. All ALT levels during the follow-up were obtained from each patient, and the changes in ALT levels during the follow-up were also assessed. Blood samples of the patients were collected after > 8 h of fasting and analyzed within 24 h. Plasma concentrations of ALT were measured using an autoanalyzer (Hitachi Modular D2400, Roche, Tokyo, Japan).

The primary endpoint was the time to disease progression, as defined by the first occurrence of any of the following: an increase of at least 2 points in the Child-Pugh score, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, bleeding gastric or esophageal varices, hepatic encephalopathy, the development of HCC or death related to liver disease[14]. HCC was diagnosed by histological evaluation or was diagnosed clinically according to the 1st edition of guidelines for the diagnosis of HCC of the Korean Association for the Study of the Liver[15]. As one of the potential risk factors for disease progression, alcohol consumption was assessed as all-or-none from available medical records. The Institutional Review Board at Samsung Medical Center reviewed and approved this study protocol.

The cumulative incidence rate of disease progression was calculated and plotted by using the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences in the incidence rate between the groups were analyzed using a log-rank test. A receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis was performed for ALT levels to estimate the best predictive cut-off values. Multivariate analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazard model for variables with P-values of < 0.05 for univariate analysis to identify factors associated with disease progression. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Table 1 presents the clinical features of the patients at study entry. Disease progression was noted in 33/232 patients (14.2%) during the median follow-up of 54.1 mo (range: 12-151 mo). The mean annual incidence rate of disease progression was 3.1%. The cause of disease progression (first occurrence) was HCC in 27 patients (11.6%), bleeding varices in 2 patients (0.9%), ≥ a 2 point increase in the Child-Pugh score in 2 patients (0.9%), and hepatic encephalopathy in 2 patients (0.9%).

| Characteristics | (n = 232) |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 57.2 ± 10.7 |

| Gender, male/female | 89 (38):143 (62) |

| Weight (kg, mean ± SD) | 61.6 ± 9.3 |

| Alcohol consumption | 32 (14) |

| Diabetes | 29 (13) |

| Estimated duration of infection (mo, median, range) | 18 (0–398) |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L, median, quartile) | 25 (19–32) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L, median, quartile) | 30 (23–48) |

| Platelet (103/mm3, median, quartile) | 179 (13–224) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase: platelet ratio index (median, range) | 0.4 (0.1–7.5) |

| > 1 | 50 (22) |

| Genotype1 | |

| 1b | 12 (57) |

| 1 others | 1 (5) |

| 2 | 8 (38) |

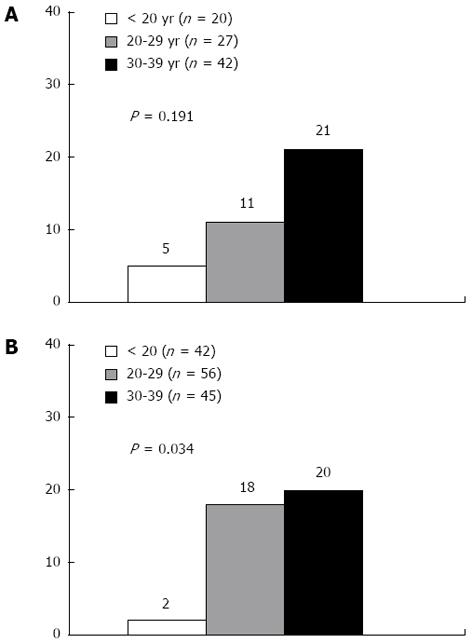

Because previous studies have suggested differing normal ALT thresholds in males and females[16-18], we analyzed data separately by gender. The ALT level (tested as a numeric variable) was significantly associated with the disease progression in both males [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.09; 95%CI: 1.01-1.21, P = 0.048] and females (HR = 1.07; 95%CI: 1.01-1.13, P = 0.040). When ALT levels were stratified, the incidence rates of disease progression were 5%, 11%, and 21% in male patients with ALT levels of < 20 IU/L (n = 20), 20-39 IU/L (n = 27), and 30-39 IU/L (n = 42), respectively (P = 0.191) (Figure 1A). In female patients, the incidence rates were 2%, 18%, and 20% with ALT levels of < 20 IU/L (n = 42), 20-39 IU/L (n = 56), and 30-39 IU/L (n = 45), respectively (P = 0.034) (Figure 1B).

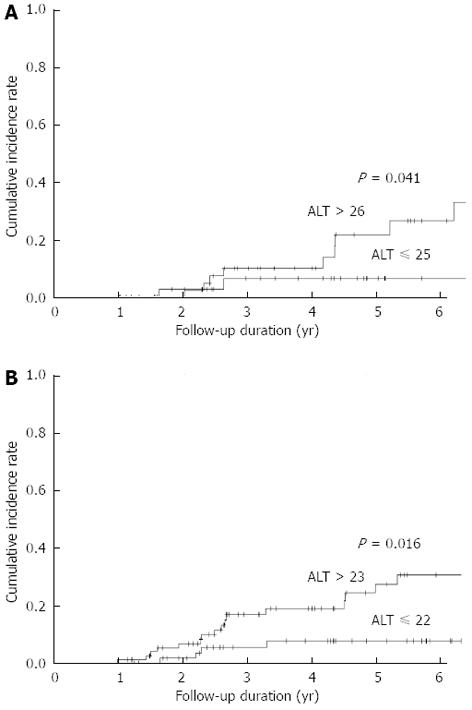

We performed ROC curve analysis to determine the best ALT cutoff value associated with disease progression. The best cutoff value was 26 IU/L in males (area = 0.722, P = 0.011, sensitivity = 0.85, specificity = 0.53) and 23 IU/L in females (area = 0.634, P = 0.055, sensitivity = 0.80, specificity = 0.47). The cumulative incidence of disease progression was significantly higher in patients with “high-normal” ALT levels than in those with “low-normal” ALT levels in both males and females (Figure 2).

The potential risk factors assessed for disease progression included the following variables: age, gender, diabetes mellitus, alcohol intake, body weight, estimated duration of infection, platelet levels, ALT levels, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels, and α-fetoprotein levels. Because HCV RNA quantitation and genotype data were available for only a few patients, these variables were not included in our analysis.

Univariate Cox proportional-hazard regression analyses revealed that age, platelet levels, AST levels, and ALT levels were significantly associated with disease progression in males (Table 2). In females, age and diabetes as well as platelet, AST, and ALT levels were associated with disease progression (Table 2). Multivariate Cox proportional-hazard regression analyses were performed for the above-mentioned variables. After adjusting for potential confounders, the baseline ALT levels remained a significant factor associated with disease progression in both genders (Table 2).

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

| Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value | |

| Male | ||||

| ALT (IU/L) > 26 vs ≤ 25 | 4.67 (1.03-21.1) | 0.045 | 5.35 (1.05-27.3) | 0.043 |

| Platelet (103/mm3) | 0.98 (0.97-0.99) | 0.002 | 0.98 (0.96-0.99) | 0.012 |

| Age (yr) | 1.07 (1.01-1.13) | 0.030 | 1.06 (0.98-1.14) | 0.12 |

| AST (IU/L) | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | < 0.001 | 1.00 (0.99-1.02) | 0.77 |

| Female | ||||

| ALT (IU/L) > 23 vs ≤ 22 | 3.51 (1.17-10.5) | 0.025 | 4.40 (1.12-15.8) | 0.023 |

| Platelet (103/mm3) | 0.97 (0.96-0.98) | < 0.001 | 0.97 (0.96-0.98) | < 0.001 |

| Age (yr) | 1.06 (1.01-1.10) | 0.017 | 1.04 (0.98-1.09) | 0.18 |

| AST (IU/L) | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | < 0.001 | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 0.97 |

| Diabetes (yes vs no) | 3.23 (1.24-8.41) | 0.016 | 2.57 (0.83-7.92) | 0.10 |

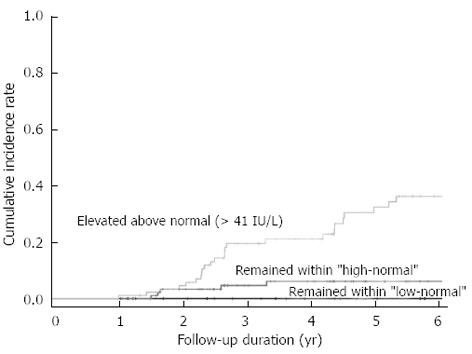

ALT levels fluctuated during the follow-up period. During the follow-up, ALT remained “low-normal” in 41 patients (17.7%), “high-normal” in 101 patients (43.5%), and elevated over > 41 IU/L in 90 patients (38.8%). More patients with “high-normal” ALT levels at baseline experienced an ALT elevation (> 41 IU/L) during follow-up than did patients with “low-normal” ALT levels at baseline (47.7% vs 27.9%, P = 0.002). The 5-year cumulative incidence of disease progression was significantly lower in patients whose ALT levels remained “low-normal” than in those patients whose ALT levels were “high-normal” or who exhibited ALT elevation > 41 U/L during follow-up (0%, 8.3% and 34.3%, P < 0.001, Figure 3).

The present study demonstrated a significant difference in the disease progression rate in chronic hepatitis C patients with “high-normal” and “low-normal” ALT levels for both genders. Because the long-term prognosis significantly differs between patients with “high-normal” ALT values and patients with “low-normal” ALT values, these findings strongly suggest that the currently used normal ALT range warrants further stratification[19-22]. This finding is consistent with findings by Lee et al[13], who investigated the incidence of HCC in a prospective cohort of chronic HCV-infected patients. The authors reported that elevated serum ALT levels were an independent risk factor for the development of HCC and that the risk begins to rise in patients with ALT levels of 15 IU/L, far below the currently used ULN for ALT levels[13]. Thus, patients with “high-normal” ALT (26 to 40 IU/L in male and 23 to 40 IU/L in female in this study) should not be considered “normal” or “healthy”, and lowering the ‘healthy’ ULN of ALT is advisable.

In this study, we enrolled patients who exhibited normal ALT levels at baseline. However, during the follow-up, many patients experienced ALT elevation. Overall, 90 of 232 patients (38.8%) exhibited ALT elevation > 41 IU/L during the follow-up. Patients with “high-normal” ALT levels exhibited a higher incidence of ALT flare (> 41 IU/L) than did patients with “low-normal” ALT levels. During follow-up, only 17.7% of patients with initially “low-normal” ALT levels persistently expressed “low-normal” ALT levels. The risk of disease progression differed significantly among patients who exhibited ALT elevation (> 41 IU/L), patients who persistently exhibited “high-normal” ALT, and patients who persistently exhibited “low-normal” ALT levels (34.3%, 8.3% and 0%, respectively). This finding emphasizes the importance of serial ALT follow-ups[20,23,24], even for patients with normal ALT levels, because ALT levels can change and disease can progress in these patients.

It is noteworthy that best cutoff value of ALT for disease progression differed according to gender in this study. Several factors influence serum ALT values, including age, race, gender and body mass index[16-18,25]. Currently, many laboratories do not assign different ULN of ALT by gender; however, several studies support the consideration of gender when setting the ULN of ALT[3,5]. In this study, we also observed different cutoff values according to gender (26 IU/L in males and 23 IU/L in females) when the ULN of ALT was calculated in terms of predicting adverse consequences. Gender-specific ULN values of ALT appear more reasonable and should be applied in clinical practice.

There are limitations to this study that require careful interpretation of our results. The mean annual incidence rate of disease progression in this study was 3.09%. Previous studies on the natural history of HCV have used various outcome measures, making it difficult to compare to this study. Nevertheless, the annual progression rate to cirrhosis in chronic HCV infection has been reported to be 0.1% to 1%[26-28]. As the endpoint of this study was advanced cirrhotic complications, the reported incidence rate in this study was very high. This study is a retrospective study that was performed at a tertiary referral center. Hence, selection bias may account for the high incidence rate of disease progression. Furthermore, a considerable proportion of the patients may have had significant fibrosis at baseline. Although baseline liver biopsies were not performed in most patients, an aspartate aminotransferase: platelet ratio index > 1, a noninvasive marker that can predict fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C patients[29], was noted in 22% of the patients at baseline.

In summary, the present study demonstrated that patients with “high-normal” ALT levels, even within the currently accepted normal range, exhibit a significantly higher risk of ALT elevation and disease progression. The optimal ALT cutoff value to predict adverse outcomes differed by gender. Thus, gender-specific and lower ALT cutoffs seem more appropriate than the currently used ALT cutoff (40 IU/mL, regardless of gender).

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is an easily available, low-cost screening tool for detecting hepatocellular disease. Currently, an upper limit of normal (ULN) of ALT has been set at the mean value ± 2SD in a group of healthy individuals. However, the ULN of ALT should also be set at a level that identifies individuals at risk for developing adverse consequences during follow-up.

Several previous studies, in which the ULN of ALT was defined as the mean value ± 2SD, have demonstrated that the ULN of ALT is lower than the currently accepted thresholds (40 IU/L).

The present study, a long-term outcome study, demonstrated that there was a significant difference in the rate of disease progression between chronic hepatitis C patients with “high-normal” and “low-normal” ALT levels for both genders.

Because the long-term prognosis significantly differs between patients with “high-normal” ALT values and patients with “low-normal” ALT values, these findings strongly suggest that the currently used normal ALT range warrants further stratification.

“High-normal” and “low-normal” refers to ALT levels that are associated with disease progression for each gender within the currently accepted normal ALT level range (< 40 IU/L).

The hepatic enzymes is indicator of liver damage, its changes must have personal specificity, individual variations is fact, regardless the gender, however, findings in this study is important.

P- Reviewer Kamal SA S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Green RM, Flamm S. AGA technical review on the evaluation of liver chemistry tests. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1367-1384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 364] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dufour DR, Lott JA, Nolte FS, Gretch DR, Koff RS, Seeff LB. Diagnosis and monitoring of hepatic injury. II. Recommendations for use of laboratory tests in screening, diagnosis, and monitoring. Clin Chem. 2000;46:2050-2068. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Lee JK, Shim JH, Lee HC, Lee SH, Kim KM, Lim YS, Chung YH, Lee YS, Suh DJ. Estimation of the healthy upper limits for serum alanine aminotransferase in Asian populations with normal liver histology. Hepatology. 2010;51:1577-1583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Oh HJ, Kim TH, Sohn YW, Kim YS, Oh YR, Cho EY, Shim SY, Shin SR, Han AL, Yoon SJ. Association of serum alanine aminotransferase and γ-glutamyltransferase levels within the reference range with metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Korean J Hepatol. 2011;17:27-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Park HN, Sinn DH, Gwak GY, Kim JE, Rhee SY, Eo SJ, Kim YJ, Choi MS, Lee JH, Koh KC. Upper normal threshold of serum alanine aminotransferase in identifying individuals at risk for chronic liver disease. Liver Int. 2012;32:937-944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Prati D, Taioli E, Zanella A, Della Torre E, Butelli S, Del Vecchio E, Vianello L, Zanuso F, Mozzi F, Milani S. Updated definitions of healthy ranges for serum alanine aminotransferase levels. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:1-10. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kang HS, Um SH, Seo YS, An H, Lee KG, Hyun JJ, Kim ES, Park SC, Keum B, Kim JH. Healthy range for serum ALT and the clinical significance of “unhealthy” normal ALT levels in the Korean population. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:292-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | De Rosa FG, Bonora S, Di Perri G. Healthy ranges for alanine aminotransferase levels. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:156-17; author reply 156-17;. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Dufour DR. Alanine aminotransferase: is it healthy to be “normal”? Hepatology. 2009;50:1699-1701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kaplan MM. Alanine aminotransferase levels: what’s normal? Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:49-51. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Senior JR. Healthy ranges for alanine aminotransferase levels. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:156-17; author reply 156-17;. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Kim HC, Nam CM, Jee SH, Han KH, Oh DK, Suh I. Normal serum aminotransferase concentration and risk of mortality from liver diseases: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2004;328:983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 391] [Cited by in RCA: 430] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lee MH, Yang HI, Lu SN, Jen CL, Yeh SH, Liu CJ, Chen PJ, You SL, Wang LY, Chen WJ. Hepatitis C virus seromarkers and subsequent risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: long-term predictors from a community-based cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4587-4593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sinn DH, Paik SW, Kang P, Kil JS, Park SU, Lee SY, Song SM, Gwak GY, Choi MS, Lee JH. Disease progression and the risk factor analysis for chronic hepatitis C. Liver Int. 2008;28:1363-1369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Park JW. [Practice guideline for diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma]. Korean J Hepatol. 2004;10:88-98. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Grossi E, Colombo R, Cavuto S, Franzini C. Age and gender relationships of serum alanine aminotransferase values in healthy subjects. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1675-1676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Leclercq I, Horsmans Y, De Bruyere M, Geubel AP. Influence of body mass index, sex and age on serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level in healthy blood donors. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 1999;62:16-20. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Poustchi H, George J, Esmaili S, Esna-Ashari F, Ardalan G, Sepanlou SG, Alavian SM. Gender differences in healthy ranges for serum alanine aminotransferase levels in adolescence. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Puoti C. HCV carriers with persistently normal aminotransferase levels: normal does not always mean healthy. J Hepatol. 2003;38:529-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Puoti C, Bellis L, Guarisco R, Dell’ Unto O, Spilabotti L, Costanza OM. HCV carriers with normal alanine aminotransferase levels: healthy persons or severely ill patients? Dealing with an everyday clinical problem. Eur J Intern Med. 2010;21:57-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Puoti C, Castellacci R, Montagnese F. Hepatitis C virus carriers with persistently normal aminotransferase levels: healthy people or true patients? Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32:634-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Puoti C, Magrini A, Stati T, Rigato P, Montagnese F, Rossi P, Aldegheri L, Resta S. Clinical, histological, and virological features of hepatitis C virus carriers with persistently normal or abnormal alanine transaminase levels. Hepatology. 1997;26:1393-1398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ahmed A, Keeffe EB. Chronic hepatitis C with normal aminotransferase levels. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1409-1415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bruce MG, Bruden D, McMahon BJ, Christensen C, Homan C, Sullivan D, Deubner H, Hennessy T, Williams J, Livingston S. Hepatitis C infection in Alaska Natives with persistently normal, persistently elevated or fluctuating alanine aminotransferase levels. Liver Int. 2006;26:643-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Prati D, Shiffman ML, Diago M, Gane E, Rajender Reddy K, Pockros P, Farci P, O’Brien CB, Lardelli P, Blotner S. Viral and metabolic factors influencing alanine aminotransferase activity in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2006;44:679-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Seeff LB. Natural history of chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:S35-S46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 476] [Cited by in RCA: 438] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Jang JY, Chung RT. Chronic hepatitis C. Gut Liver. 2011;5:117-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Marcellin P, Asselah T, Boyer N. Fibrosis and disease progression in hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:S47-S56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Shaheen AA, Myers RP. Diagnostic accuracy of the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for the prediction of hepatitis C-related fibrosis: a systematic review. Hepatology. 2007;46:912-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |