Published online Mar 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i12.1997

Revised: December 10, 2012

Accepted: December 22, 2012

Published online: March 28, 2013

Processing time: 124 Days and 20.2 Hours

Transmesenteric hernias have bimodal distribution and occur in both pediatric and adult patients. In the adult population, the cause is iatrogenic, traumatic, or inflammatory. We report a case of transmesocolic hernia in an elderly person without any preoperative history. An 84-year-old Korean female was admitted with mid-abdominal pain and distension for 1 d. On abdominal computed tomography, we diagnosed transmesocolic hernia with strangulated small bowel obstruction, and performed emergency surgery. The postoperative period was uneventful and she was discharged 11 d after surgery. Hence, it is important to consider the possibility of transmesocolic hernia in elderly patients with signs and symptoms of intestinal obstruction, even in cases with no previous surgery.

- Citation: Jung P, Kim MD, Ryu TH, Choi SH, Kim HS, Lee KH, Park JH. Transmesocolic hernia with strangulation in a patient without surgical history: Case report. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(12): 1997-1999

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i12/1997.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i12.1997

The incidence of internal hernia is less than 1%[1], and transmesocolic hernia is a particularly rare type of internal hernia. The overall mortality is more than 50% in cases with strangulated small bowel obstruction[2]. In adults, transmesocolic hernias are most often caused by previous surgical procedures, abdominal trauma or intraperitoneal inflammation, and transmesocolic hernia in a person without a surgical history is extremely rare. We report such a case of transmesocolic hernia with strangulated intestinal obstruction.

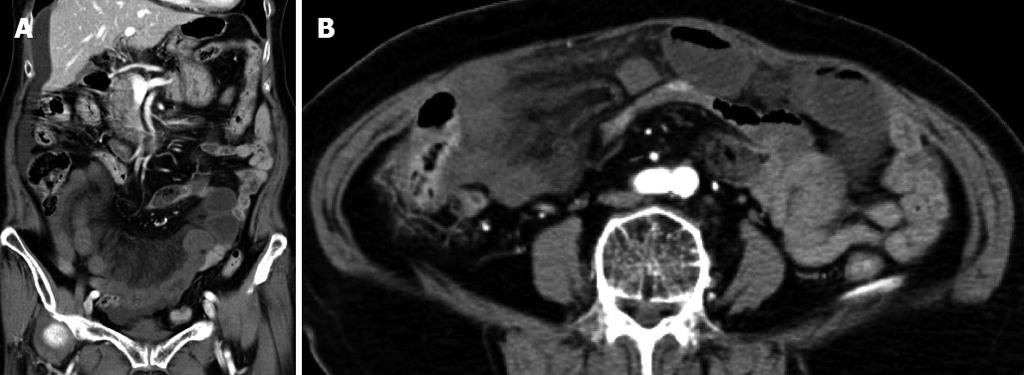

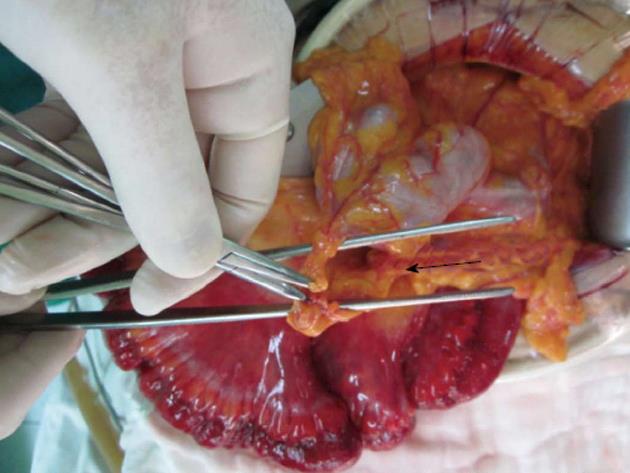

An 84-year-old Korean female, with no past history of surgery, was admitted with mid-abdominal pain and distension for 1 d. Upon admission, her blood pressure was 120/80 mmHg, heart rate 72 beats/min, and body temperature 36.6 °C. On physical examination of the area of concern, mid-abdominal tenderness was observed. On admission, laboratory assessments were as follows: white blood cell count 14 500/mm3 (segmented neutrophil 91.4%), hemoglobin concentration 12.8 g/dL, platelet count 272 000/mm3, sodium 135 mmol/L, potassium 4.5 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 21.5 mg/dL, creatinine 0.9 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 18 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase 10 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 256 IU/L, lactate dehydrogenase 415 IU/L, γ-glutamyltransferase 17 IU/L, and C-reactive protein 1.04 mg/dL. A simple abdominal X-ray showed distended small bowel loops. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed crowded small bowel loops (from distal jejunum to proximal ileum), with circumferential wall thickening and decreased enhancement in the middle and lower abdomen, and stretched mesenteric vessels with mesenteric edema (Figure 1). We diagnosed transmesocolic hernia with intestinal obstruction and performed emergency surgery. During the operation, a herniated small intestine with strangulation by perforated omentum was noted below the transverse colon (Figure 2). Strangulated herniation was seen 190 cm from the ligament of Treiz, for a length of 160 cm. The strangulated small intestine herniation was resected and the omentum defect was closed. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 11, with a favorable follow-up as an outpatient for 1 mo.

An internal hernia is the protrusion of an abdominal organ through a normal or abnormal mesenteric or peritoneal aperture[3]. An internal hernia can be acquired as a result of trauma or a surgical procedure, or may be constitutional and related to congenital peritoneal defects. In the broad category of internal hernias, there are several main types based on their location, as traditionally described by Meyers. These consist of paraduodenal (53%), pericecal (13%), foramen of Winslow-related (8%), transmesentric and transmesocolic (8%), intersigmoid (6%), and retroanastomotic (5%), with the overall incidence of internal hernia being 0.2%-0.9%[2]. The transmesenteric hernia has three main types: transmesocolic, through a small-bowel mesenteric defect, and Peterson’s

hernia[1]. Most transmesocolic hernias in children result from a congenital defect in the small bowel mesentery close to the ileocecal region. Congenital defects occur following the embryonic formation of an intestinal loop in thin avascular areas of the mesentery (e.g., the mesenteries of the lower ileum, the sigmoid mesocolon, and the transverse mesocolon). As a consequence, there are multiple theories of congenital causes of such mesenteric defects[4]. It is likely that the congenital condition is associated with prenatal intestinal ischemic accidents due to the observed frequently in infants with atretic bowel segments. In adults, transmesocolic hernias are most often caused by previous surgical procedures, abdominal trauma or intraperitoneal inflammation. When the small bowel is herniated through a defect in the mesentery or omentum, the herniated bowel is compressed against the abdominal wall. In this case, the herniated bowel is clustered and lies outside the colon which is displaced centrally[5].

Transmesocolic hernias are more likely than other subtypes to develop volvulus and strangulation, or ischemia, the reported incidence of which are as high as 30% and 40%, respectively, with mortality rates of 50% for treated groups and 100% for non-treated subgroups[2,6]. Clinically, internal hernias can be asymptomatic, or can cause discomfort ranging from constant vague epigastric pain to intermittent colicky periumbilical pain, while additional symptoms include nausea and vomiting[1].

An internal hernia is difficult to diagnosis by physical examination, and the most important diagnostic method is abdominal CT. It has been suggested that the two findings of a peripherally located small bowel, and lack of omental fat between the loops and the anterior abdominal wall, might be the most helpful CT signs, with an overall sensitivity of 85% and 92% for each respective finding[6,7]. Observation of the clustering of small bowel loops and an abnormality in the mesenteric vessels are helpful findings on abdominal CT.

In adults, a previous surgical procedure, as well as trauma or inflammation are the most common causes of transmesocolic hernia. Our case was a rare presentation in an elderly person without a history of trauma, and without previous surgery[8-12]. The patient had non-specific symptoms and signs on plain abdominal X-ray, but also non-specific abdominal distension upon physical examination. In the case of internal hernia, these defects may be idiopathic, but we can speculate that a small congenital defect existed without any hernia, and enlarged due to the aging. A transmesocolic hernia is difficult to diagnosis preoperatively despite the array of diagnostic techniques currently available. In patients suspected of having an internal hernia, early surgical intervention may be advisable due to the high morbidity and mortality rates. Therefore, it is important to consider the possibility of a transmesocolic hernia when patients have signs and symptoms of intestinal obstruction, even in cases of elderly patients with no previous surgical history.

P- Reviewer Mizrahi S S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Martin LC, Merkle EM, Thompson WM. Review of internal hernias: radiographic and clinical findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:703-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 371] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Meyers MA. Dynamic radiology of the abdomen: normal and pathologic anatomy, 5th ed. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag 2000; 711-748. |

| 3. | Mathieu D, Luciani A. Internal abdominal herniations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:397-404. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Treves F. Lectures on the Anatomy of the Intestinal Canal and Peritoneum in Man. Br Med J. 1885;1:470-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tauro LF, Vijaya G, D’Souza CR, Ramesh HC, Shetty SR, Hegde BR, Deepak J. Mesocolic hernia: an unusual internal hernia. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:141-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Blachar A, Federle MP. Internal hernia: an increasingly common cause of small bowel obstruction. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2002;23:174-183. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Takeyama N, Gokan T, Ohgiya Y, Satoh S, Hashizume T, Hataya K, Kushiro H, Nakanishi M, Kusano M, Munechika H. CT of internal hernias. Radiographics. 2005;25:997-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Park HS, Kim JI, Kim MS, Kim SS, Cho SH, Park SH, Han JY, Kim JK. [A case of transmesocolic hernia in elderly person without a history of operation]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006;48:286-289. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Ueda J, Yoshida H, Makino H, Yokoyama T, Maruyama H, Hirakata A, Ueda H, Watanabe M, Uchida E, Uchida E. Transmesocolic hernia of the ascending colon with intestinal obstruction. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2012;6:344-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sivit CJ. CT scan of mesentery-omentum peritoneum. Radiol Clin North Am. 1996;34:863-884. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Yoo E, Kim JH, Kim MJ, Yu JS, Chung JJ, Yoo HS, Kim KW. Greater and lesser omenta: normal anatomy and pathologic processes. Radiographics. 2007;27:707-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chatterjee S, Chatterjee S, Kumar S, Gupta S. Acute intestinal obstruction: a rare aetiology. Case Rep Surg. 2012;2012:501209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |