Published online Feb 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i7.698

Revised: June 24, 2011

Accepted: July 1, 2011

Published online: February 21, 2012

AIM: To investigate the efficacy and safety of imatinib dose escalation in Chinese patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST).

METHODS: Advanced GIST patients previously failing 400 mg imatinib treatment were enrolled in this study. Patients received imatinib with dose escalation to 600 mg/d, and further dose escalation to 800 mg/d if imatinib 600 mg/d failed. Progression-free survival, overall survival, clinical efficacy, c-kit/PDGFRA genotype and safety were evaluated.

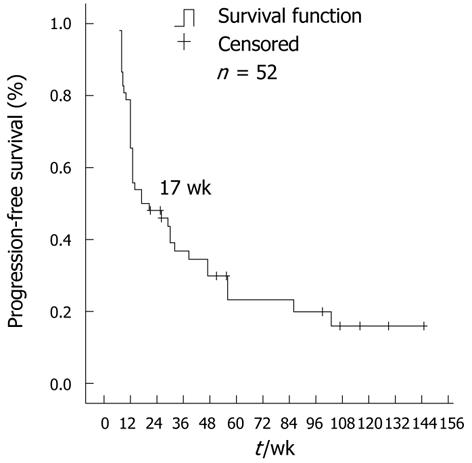

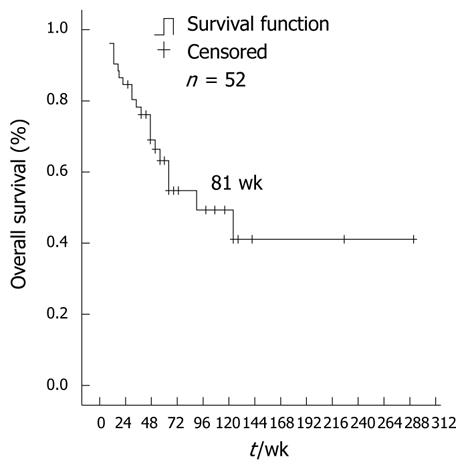

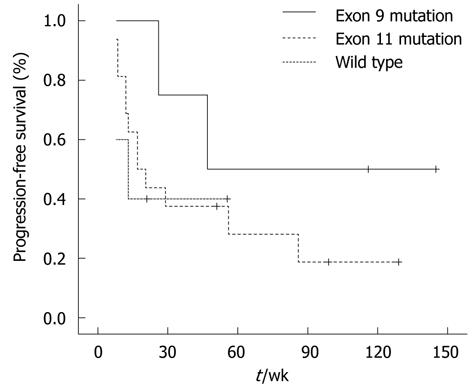

RESULTS: 52 patients were enrolled in this study. For the 47 evaluable patients receiving imatinib (600 mg/d), the disease control rate was 40.4%, and the median progression-free survival for all patients was 17 wk (95% CI: 3.9-30.1). The median overall survival after dose escalation was 81 wk (95% CI: 36.2-125.8). Adverse events, mainly edema, fatigue, granulocytopenia and skin rash were tolerable. However, further dose escalation (800 mg/d) in 14 cases was ineffective, with disease progression and severe adverse events. Among 30 cases examined for gene mutations, patients with exon 9 mutations experienced a better progression-free survival of 47 wk.

CONCLUSION: Imatinib dose escalation to 600 mg/d is more appropriate for Chinese patients and may achieve further survival benefit.

- Citation: Li J, Gong JF, Li J, Gao J, Sun NP, Shen L. Efficacy of imatinib dose escalation in Chinese gastrointestinal stromal tumor patients. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(7): 698-703

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i7/698.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i7.698

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are tumors that may occur throughout the gastrointestinal tract and in the omentum and mesentery, and account for about 2% of gastrointestinal tract tumors[1]. Various types of KIT gene mutations are present in the majority of GISTs[2]. Imatinib mesylate, a molecular tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting KIT, platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) and/or bcr-abl has remarkable clinical efficacy in the treatment of advanced GIST. Imatinib mesylate 400 mg/d is recommended in the first-line treatment of advanced GIST[3,4]. However, about 5% of patients show primary resistance to imatinib and about 50% of patients develop secondary resistance within a median treatment duration of 2 years[4,5].

The results of two studies proved that after the failure of first-line treatment with imatinib 400 mg/d an escalated dose (800 mg/d) can still achieve tumor control and confer further survival benefits in some patients[6,7]. However, these studies were conducted in Western countries, thus whether Chinese patients with advanced GIST could benefit from an escalated dose of imatinib is unclear. It is also unknown whether increased dose increments are tolerated in these patients, due to differences in body weight and race between Chinese patients and Western patients.

KIT gene mutations can predict the objective efficacy of imatinib in the first-line treatment of advanced GIST[8], however, the relevance of these mutations to the objective response of imatinib dose escalation has not yet been reported. In this study, Chinese patients with advanced GIST, previously treated with 400 mg/d imatinib and who received dose escalation therapy, were examined to evaluate the median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) after imatinib dose escalation, objective efficacy, relationships between gene mutation types and efficacy, and the safety of imatinib dose escalation.

This was a single arm, open-label, prospective study designed to evaluate the objective response and safety of imatinib dose escalation in Chinese GIST patients with resistance to imatinib 400 mg/d. The primary end point was PFS and the secondary end points were OS, disease control rate (DCR) defined as a combination of complete response (CR) + partial response (PR) + stable disease (SD), relationships between the gene mutation types and objective responses, and safety of imatinib dose escalation.

Adult patients (age ≥ 18 years) with a histologically confirmed recurrent or metastatic GIST which was CD117 positive, and who failed prior imatinib 400 mg/d treatment were eligible for the trial. The pathological and CD117 diagnosis was made immunohistochemically. All patients were Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 2 or lower and provided informed consent. Patients were assigned to receive imatinib 600 mg/d orally, taken once daily with food, in the form of 100 mg capsules. If the disease progressed after imatinib 600 mg therapy, the dose of imatinib was further increased to 800 mg/d until the next instance of tumor progression or tolerance failure. CT or MRI examination was conducted every 8 wk and the objective response was based on the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) guidelines. The PFS was defined as the time from the first dose of imatinib 600 mg/d to the occurrence of progression, death from any cause, or withdrawal from the trial. OS was defined as the time from the first dose of imatinib 600 mg/d to the occurrence of death from any cause. Adverse events were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 2.0.

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissue samples, taken prior to imatinib treatment, were collected for KIT and PDGFR gene mutation analyses. Genomic DNA was extracted from the tumor sample using the e.Z.N.A. FFPE DNA Kit (OMEGA Bio-Tek Inc., Norcross, GA, United States). Initially, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and mutational analyses of KIT exon 11 were performed. Patient samples negative for KIT exon 11 mutations were subsequently amplified with primers specific for KIT exons 9, 13, and 17. When KIT mutations were not identified, additional mutational analyses were conducted for exons 12 and 18 of the PDGFR gene.

All statistical analyses were based on the SPSS 15.0 platform (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). PFS and OS curves were constructed according to the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test was used to compare differences between PFS curves. Frequency and percentage descriptions were used for categorical variables and the chi-square test was conducted to compare the incidence of different events. If the theoretical frequency was lower than 1, Fisher’s exact test was conducted. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD and mean differences between two groups were compared using Student’s t-test.

Between April 2004 and March 2009, 168 patients with advanced GIST received imatinib 400 mg/d. Of these patients, 52 were eligible for imatinib dose escalation therapy. Most of the patients had secondary resistance (96%) and two had primary resistance. The duration of imatinib 400 mg/d treatment ranged from 3.0 to 56.0 mo, with a median PFS of 20.0 mo (95% CI: 15.3-24.7). Before the initiation of imatinib dose escalation, three patients with progression in liver metastasis and one patient with new-onset pelvic metastasis received complete tumor resection, while one patient with liver metastasis received local radiofrequency ablation therapy and four patients received primary palliative surgical resection. The 52 eligible patients received imatinib dose escalation therapy of 600 mg/d orally. The clinical features of these patients are shown in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Patients |

| Sex | |

| Male | 34 (65.4) |

| Female | 18 (34.6) |

| Age (yr) (mean ± SD) | 53.8 ± 14.0 |

| Primary site | |

| Stomach | 18 (34.6) |

| Small intestine | 20 (38.5) |

| Abdominal cavity | 9 (17.3) |

| Colon | 2 (3.8) |

| Rectum | 2 (3.8) |

| Pelvis | 1 (1.9) |

| Prior surgical resection | |

| Yes | 47 (90.4) |

| No | 5 (9.6) |

| Site of metastasis | |

| Liver | 29 (55.8) |

| Abdominal cavity | 31 (59.6) |

| Pelvis | 6 (11.5) |

| Lung | 1 (1.9) |

| Bone | 1 (1.9) |

| Subcutaneous | 1 (1.9) |

| Prior response to imatinib 400 mg/d | |

| Complete remission | 5 (9.6) |

| Partial remission | 27 (51.9) |

| Stable disease | 18 (34.6) |

| Progressive disease | 2 (3.8) |

| Receiving regional treatment prior to dose escalation | |

| Complete tumor resection | 4 (7.7) |

| Palliative tumor resection | 4 (7.7) |

| Local Radiofrequency ablation treatment | 1 (1.9) |

| No regional treatment | 43 (82.7) |

Dose escalation therapy of imatinib 600 mg/d was well tolerated. All 52 patients had Grade 1 or 2 adverse events and only 7 patients had Grade 3 adverse events. Adverse events consisted of edema, fatigue, granulocytopenia and skin rash. Adverse events more severe than those found in the previous 400 mg/d treatment were experienced by 73.1% of patients, particularly edema and fatigue. Imatinib dose was reduced to 500 mg/d in one patient due to fatigue and abdominal pain. In other patients, 600 mg/d was well tolerated and discontinuation of imatinib was not required due to adverse events.

The dose of imatinib was further escalated to 800 mg/d in 14 patients due to disease progression during 600 mg/d treatment. All 14 patients had Grade 1 or 2 adverse events and showed worsening adverse events; predominantly edema, fatigue, abdominal pain, nausea, and loss of appetite. Among these patients, 6 had Grade 3 adverse events, and imatinib was discontinued in three and dose reduction to 600 mg/d in two. Hematologic and non-hematologic toxicities are summarized in Table 2.

| Imatinib 600 mg/d | Imatinib 800 mg/d | |||

| Grade 1-2 (%) | Grade 3-4 (%) | Grade 1-2 (%) | Grade 3-4 (%) | |

| Edema | 42 (80.8) | 0 (0) | 14 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Fatigue | 32 (61.5) | 1 (1.9) | 9 (64.3) | 5 (35.7) |

| Granulocytopenia | 19 (36.5) | 3 (5.8) | 5 (35.7) | 1 (7.1) |

| Skin rash | 12 (23.1) | 2 (3.8) | 7 (50.0) | 1 (7.1) |

| Anemia | 7 (13.5) | 2 (3.8) | 5 (35.7) | 0 (0) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0) |

| Anorexia | 8 (15.4) | 1 (1.9) | 6 (42.9) | 0 (0) |

| Nausea | 11 (21.2) | 1 (1.9) | 6 (42.9) | 0 (0) |

| Alopecia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (14.3) | 0 (0) |

| Abdominal pain | 11 (21.2) | 0 (0) | 7 (50.0) | 0 (0) |

| Diarrhea | 5 (9.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0) |

| Epiphora | 2 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (14.3) | 0 (0) |

Of 52 patients, four were excluded due to complete tumor resection and one patient received local radiofrequency ablation therapy prior to dose escalation therapy. The remaining 47 patients all had measurable disease according to RECIST criteria and tumor assessment was performed at least once. Among these patients, three (6.4%) achieved PR, 16 (34.0%) had SD, and 28 (59.6%) showed disease progression (PD) after imatinib dose escalation to 600 mg/d. The overall DCR was 40.4%.

Fourteen patients with disease progression on 600 mg/d imatinib received further dose escalation to 800 mg/d, of which three patients discontinued therapy due to adverse reactions. Eleven patients with measurable disease all showed PD.

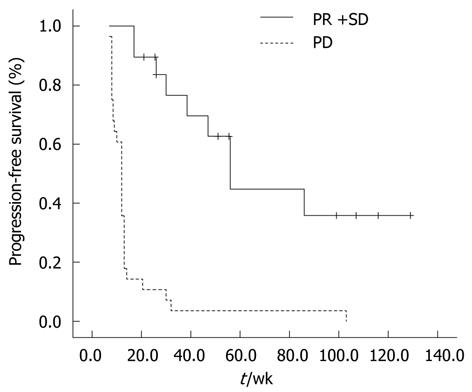

As of February 2011, 48 patients (92.3%) had progression after imatinib 600 mg/d treatment. The median PFS for all 52 patients was 17 wk (95% CI: 3.9-30.1) (Figure 1). Patients with PR or SD had a significantly longer PFS than patients who progressed on 600 mg/d dose escalation therapy. The median PFS for patients with PR or SD was 51 wk (95% CI: 26.8-75.2) and was 12 wk for patients with PD (95% CI: 10.6-13.4) (P < 0.001) (Figure 2).

As of February 2011, 13 patients were alive, 38 patients had died due to tumor progression and 1 patient had died due to other reasons. The median OS following dose escalation in all patients, starting from the first prescription of 600 mg/d imatinib, was 81 wk (95% CI: 36.2-125.8) (Figure 3). The 1-year survival rate for all patients was 63.5%.

Of the four patients who received complete resection of tumor metastasis before dose escalation, two experienced tumor recurrence and died of tumor progression. PFS in these two cases was 48 wk and 29 wk, respectively, and OS was 90 wk and 51 wk, respectively. The other two patients, and one patient receiving microwave treatment of local liver metastasis, had no recurrence; PFS was 135 wk, 151 wk, and 145 wk, respectively.

A total of 30 patients underwent gene mutation analysis before first-line imatinib 400 mg/d treatment, of which 19 (63.3%) had a mutation in KIT exon 11, 6 (20.0%) in KIT exon 9, and two (6.7%) in KIT exon 13. The remaining five (10.0%) patients showed wild-type GIST. No PDGFR gene mutations were found.

Among the 19 patients with KIT exon 11 mutations, 17 were evaluable. One patient achieved a PR and 7 patients remained stable. The remaining 9 patients progressively worsened. The overall DCR was 47.1%. Among the 4 evaluable KIT exon 9 patients, 1 achieved PR and 3 displayed SD. In the 3 evaluable wild-type GIST patients, 1 stabilized and the remaining 2 had PD. In patients with KIT exon 13 mutations, one was stable and the other had PD.

The median PFS of patients with KIT exon 11 mutations, KIT exon 9 mutations, and KIT/PDGFR wild-type patients was 21 wk (95% CI: 3.4-37.6), 47 wk (95% CI: 11.6-82.4), and 8 wk, respectively, as shown in Figure 4.

Although the difference in PFS between the three categories was not significant (P = 0.083), patients with KIT exon 9 mutations tended to have longer PFS than those with exon 11 mutations and wild-type patients.

Up to February 2011, of 52 patients, 4 are progression-free and continue to receive imatinib 600 mg/d treatment. All patients receiving further dose escalation to imatinib 800 mg/d have discontinued treatment. 21 patients received sunitinib treatment. 39 patients died due to tumor progression with the exception of 1 patient.

The efficacy of imatinib mesylate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors was confirmed and patients with advanced disease can achieve prolonged OS. Imatinib 400 mg/d is recommended as the first-line treatment for advanced GIST patients. However, a proportion of GIST patients experience secondary resistance to imatinib after tumor remission, and tumor progression occurs. Results of the phase III trials, EORTC62005 and US0033, confirmed that after resistance to 400 mg/d imatinib, dose escalation therapy to 800 mg/d can offer further disease control in 30%-40% of patients[6,7]. The results of the analyses in these two studies showed that patients obtained a PFS benefit of 11.3 and 21.4 wk after cross-over to 800 mg/d imatinib, which represents a further survival benefit for a number of GIST patients[9].

The conclusions in the present study are consistent with those of the above-mentioned studies: imatinib 600 mg/d dose escalation treatment improved PFS and OS of patients after progression on imatinib 400 mg/d. The PFS of patients achieving PR and SD was superior to that of patients with PD, suggesting that disease remission or control may bring about a benefit in PFS. In addition, late follow-up revealed that about 40% of patients received sunitinib after failure of imatinib escalation treatment. Sunitinib, a multi-target tyrosine kinase inhibitor, provided prolonged OS for imatinib-resistant patients in a phase III trial[10]. Thus, due to an unclear mechanism, sunitinib also contributed to the median OS of 81 wk.

In this study, of the 11 patients with evaluable disease receiving imatinib 800 mg/d dose escalation therapy, none of these patients benefited from this escalation, and adverse events were severe and intolerable. The results of the EORTC62005 and US0033 studies showed that Western patients were tolerant to imatinib 800 mg/d. However, because Chinese patients tend to have a smaller body surface area than Western patients, it is unclear whether Chinese patients can tolerate imatinib 800 mg/d dose escalation therapy. In this study, the median PFS of Chinese patients receiving 600 mg/d dose escalation therapy was similar to the PFS of Western groups in the two phase III trials, and imatinib 600 mg/d dose escalation was generally well-tolerated. In addition, since none of the patients benefited from imatinib dose escalation therapy to 800 mg/d and adverse events were severe, imatinib dose escalation to 800 mg/d is not recommended when imatinib 600 mg/d is ineffective for the treatment of Chinese patients with advanced GIST.

Some gene mutations can predict the objective efficacy of imatinib for advanced GIST[8]. In addition, results from the EORTC62005 study have shown that, during the initial treatment, imatinib 800 mg/d may significantly prolong PFS in patients with GISTs harboring exon 9 mutations, although no further improvement in PFS was seen in patients with KIT exon 11 mutations[9]. However, the relationship between gene mutations and the efficacy of imatinib dose escalation therapy following secondary imatinib resistance is unclear. Previous studies have shown that secondary resistance to imatinib might be related to a secondary c-kit/PDGFRA mutation, gene amplification, or imatinib-related drug resistance due to changes in drug metabolism[11-13]. A recent, small sample size study[14] in Korea reported that dose escalation of imatinib to 600 mg/d or 800 mg/d following 400 mg/d treatment failure can produce better outcomes in patients with exon 9 mutations than with other mutation types. Due to the difficulty in obtaining tissue samples following drug resistance, the analysis of secondary gene mutations was not possible. Thus, the gene mutation analyses were conducted on tissue samples taken prior to the start of imatinib treatment. Similar to the results of the Korean study, patients with exon 9 mutations had a relatively long PFS after receiving imatinib dose escalation therapy. Although the sample size, especially the number of patients with exon 9 mutations, was comparatively small, and the results of the analysis of PFS with different mutation types showed no statistical difference, patients with exon 9 mutations showed a trend towards longer PFS following imatinib dose escalation therapy. Moreover, although the results of the EORTC62005 study showed that first-line treatment with imatinib 800 mg/d may not improve the objective efficacy and PFS in KIT exon 11 mutation patients compared with standard treatment of imatinib 400 mg/d, a proportion of KIT exon 11 mutation patients can still achieve disease control with dose escalation therapy after progression on previous treatment with imatinib 400 mg/d. As for KIT exon 11 mutation patients, dose escalation therapy is still one of the available treatment strategies following failure of imatinib standard treatment.

The NCCN guidelines recommend that GISTs with exon 9 mutations should receive high-dose imatinib treatment. Whether these patients can receive standard imatinib treatment followed by high-dose imatinib treatment following disease progression is still not known. Since the number of patients with exon 9 mutations in the present study was very small, no conclusion can be made. It is hoped that the EORTC62005 and S0033 studies will provide further insight.

A variety of molecular targeted compounds are available or under development to overcome imatinib resistance. These include the new generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor, nilotinib, the multiple kinase inhibitor sorafenib, and the molecular target of rapamycin inhibitor, everolimus, all of which have been shown to be effective in overcoming imatinib resistance in phase I or II studies of advanced GIST patients[15-17]. As a multi-target tyrosine kinase inhibitor, sunitinib has been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of patients with advanced GIST whose disease has progressed on imatinib treatment. For patients who failed prior standard dose imatinib treatment, there has been no direct evidence to suggest whether it is preferable to use imatinib dose escalation therapy or switch to second-line treatment with sunitinib. An expanded, global, retrospective analysis of sunitinib showed that the OS of patients who received previous imatinib treatment of ≤ 400 mg/d was 93 wk, which was superior to the 70 wk observed in patients previously receiving > 400 mg/d imatinib, suggesting that patients previously receiving comparatively small doses of imatinib may obtain greater survival benefit after sunitinib treatment[18]. However, this suggestion still does not answer the above question, and further evidence is needed to select between the two secondary treatment strategies.

Dose escalation therapy to 600 mg/d after treatment failure with imatinib 400 mg/d is more appropriate for Chinese patients with advanced GIST due to good tolerability and survival benefits. Regarding the comparatively poor objective efficacy and severe adverse events, further escalation of imatinib dose to 800 mg/d following imatinib 600 mg/d failure is not recommended.

Imatinib 400 mg/d is recommended as the standard first-line treatment for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). An escalated dose (800 mg/d) can still achieve tumor control and confer further survival benefits after failure with imatinib 400 mg/d in some patients. However, whether Chinese patients with advanced GIST could benefit from an escalated dose of imatinib is unclear. It is also unknown whether increased dose increments are tolerated in these patients, due to differences in body weight and race between Chinese patients and Western patients. KIT gene mutation can predict the objective efficacy of imatinib in the first-line treatment of advanced GIST, however, its relevance to the objective response of imatinib dose escalation has not yet been reported.

In this study, the authors demonstrate that imatinib dose escalation was effective in some Chinese GIST patients after failure of imatinib standard dose, and KIT genotype could predict the efficacy of imatinib dose escalation treatment.

This is the first report of imatinib dose escalation treatment for GIST in Chinese patients and the results showed imatinib escalation to 600 mg/d was more appropriate for Chinese patients than imatinib 800 mg/d. There are few reports on the relationship between KIT genotype and the efficacy of imatinib dose escalation. This study demonstrated that patients with KIT exon 9 mutations benefited more from imatinib dose escalation treatment.

The results of this study help to clarify the efficacy and safety of imatinib dose escalation treatment in Chinese GIST patients. More importantly, the appropriate treatment dose between Western patients and Chinese patients may be different. Genotype may be helpful in predicting the efficacy of imatinib dose escalation treatment.

Generally, this is an interesting and well-done study that even though its patient size limits the conclusions of the genetic studies, it provides important clinical information for the management of these patients with higher drug doses.

Peer reviewer: Robert Jensen, MD, Digestive Disease Branch, National Institutes of Health, Building 10, Rm 9C-103, Bethesda, MD 20892, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Joensuu H, Fletcher C, Dimitrijevic S, Silberman S, Roberts P, Demetri G. Management of malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:655-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 383] [Cited by in RCA: 395] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tosoni A, Nicolardi L, Brandes AA. Current clinical management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2004;4:595-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | van Oosterom AT, Judson I, Verweij J, Stroobants S, Donato di Paola E, Dimitrijevic S, Martens M, Webb A, Sciot R, Van Glabbeke M. Safety and efficacy of imatinib (STI571) in metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumours: a phase I study. Lancet. 2001;358:1421-1423. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Blanke CD, Van den Abbeele AD, Eisenberg B, Roberts PJ, Heinrich MC, Tuveson DA, Singer S, Janicek M. Efficacy and safety of imatinib mesylate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:472-480. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Verweij J, Casali PG, Zalcberg J, LeCesne A, Reichardt P, Blay JY, Issels R, van Oosterom A, Hogendoorn PC, Van Glabbeke M. Progression-free survival in gastrointestinal stromal tumours with high-dose imatinib: randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1127-1134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Blanke CD, Rankin C, Demetri GD, Ryan CW, von Mehren M, Benjamin RS, Raymond AK, Bramwell VH, Baker LH, Maki RG. Phase III randomized, intergroup trial assessing imatinib mesylate at two dose levels in patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing the kit receptor tyrosine kinase: S0033. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:626-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zalcberg JR, Verweij J, Casali PG, Le Cesne A, Reichardt P, Blay JY, Schlemmer M, Van Glabbeke M, Brown M, Judson IR. Outcome of patients with advanced gastro-intestinal stromal tumours crossing over to a daily imatinib dose of 800 mg after progression on 400 mg. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1751-1757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Demetri GD, Blanke CD, von Mehren M, Joensuu H, McGreevey LS, Chen CJ, Van den Abbeele AD, Druker BJ. Kinase mutations and imatinib response in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4342-4349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Patel S, Zalcberg JR. Optimizing the dose of imatinib for treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumours: lessons from the phase 3 trials. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:501-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Demetri GD, Huang X, Garrett CR, Schöffski P, Blackstein ME, Shah MH. Novel statistical analysis of long-term survival to account for crossover in a phase III trial of sunitinib (SU) vs. placebo (PL) in advanced GIST after imatinib (IM) failure. 2008;. |

| 11. | Agaram NP, Besmer P, Wong GC, Guo T, Socci ND, Maki RG, DeSantis D, Brennan MF, Singer S, DeMatteo RP. Pathologic and molecular heterogeneity in imatinib-stable or imatinib-responsive gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:170-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Debiec-Rychter M, Cools J, Dumez H, Sciot R, Stul M, Mentens N, Vranckx H, Wasag B, Prenen H, Roesel J. Mechanisms of resistance to imatinib mesylate in gastrointestinal stromal tumors and activity of the PKC412 inhibitor against imatinib-resistant mutants. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:270-279. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Widmer N, Decosterd LA, Csajka C, Leyvraz S, Duchosal MA, Rosselet A, Rochat B, Eap CB, Henry H, Biollaz J. Population pharmacokinetics of imatinib and the role of alpha-acid glycoprotein. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:97-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Park I, Ryu MH, Sym SJ, Lee SS, Jang G, Kim TW, Chang HM, Lee JL, Lee H, Kang YK. Dose escalation of imatinib after failure of standard dose in Korean patients with metastatic or unresectable gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009;39:105-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Proceedings of the 44th American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; May 30-June 03; Chicago: American Society of Clinical Oncology, 2008: 10523. . |

| 16. | Wiebe L, Kasza KE, Maki RG, D'Adamo DR, Chow WA, Wade JL. Activity of sorafenib (SOR) in patients (pts) with imatinib (IM) and sunitinib (SU)-resistant (RES) gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): A phase II trial of the University of Chicago Phase II Consortium. Proceedings of the 44th American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; May 30-June 03; Chicago: American Society of Clinical Oncology 2008; 10502. |

| 17. | Dumez H, Reichard P, Blay JY, Schöffski P, Morgan JA, Ray-Coquard IL. CRAD001C2206 Study Group. A phase I-II study of everolimus (RAD001) in combination with imatinib in patients (pts) with imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST). Proceedings of the 44th American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; May 30-June 03; Chicago: American Society of Clinical Oncology 2008; 10519. |

| 18. | Reichardt P, Kang Y, Ruka W, Seddon B, Guerriero A, Breazna A. Detailed analysis of survival and safety with sunitinib (SU) in a worldwide treatment-use trial of patients with advanced GIST. Proceedings of the 44th American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; May 30-June 03; Chicago: American Society of Clinical Oncology 2008; 10548. |