Published online Nov 14, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i42.6168

Revised: August 6, 2012

Accepted: August 14, 2012

Published online: November 14, 2012

Venous complications in patients with acute pancreatitis typically occur as a form of splenic, portal, or superior mesenteric vein thrombosis and have been detected more frequently in recent reports. Although a well-organized protocol for the treatment of venous thrombosis has not been established, anticoagulation therapy is commonly recommended. A 73-year-old man was diagnosed with acute progressive portal vein thrombosis associated with acute pancreatitis. After one month of anticoagulation therapy, the patient developed severe hematemesis. With endoscopy and an abdominal computed tomography scan, hemorrhages in the pancreatic pseudocyst, which was ruptured into the duodenal bulb, were confirmed. After conservative treatment, the patient was stabilized. While the rupture of a pseudocyst into the surrounding viscera is a well-known phenomenon, spontaneous rupture into the duodenum is rare. Moreover, no reports of upper gastrointestinal bleeding caused by pseudocyst rupture in patients under anticoagulation therapy for venous thrombosis associated with acute pancreatitis have been published. Herein, we report a unique case of massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to pancreatic pseudocyst rupture into the duodenum, which developed during anticoagulation therapy for portal vein thrombosis associated with acute pancreatitis.

- Citation: Park WS, Kim HI, Jeon BJ, Kim SH, Lee SO. Should anticoagulants be administered for portal vein thrombosis associated with acute pancreatitis? World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(42): 6168-6171

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i42/6168.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i42.6168

The vascular complications of pancreatitis are major causes of morbidity and mortality and are typically related to hemorrhage. Venous complications generally occur as a form of thrombosis in the splenic vein and less commonly in the portal or superior mesenteric vein[1]. Although no randomized controlled trial regarding the use of anticoagulants in acute portal vein thrombosis has been conducted, the use of unfractionated heparin, with subsequent transition to oral warfarin, is the most common approach to anticoagulation[2,3].

Pancreatic pseudocysts are common findings, but spontaneous rupture occurs infrequently. Pseudocyst rupture can occur in the free peritoneal cavity, stomach, duodenum, colon, portal vein, pleural cavity, and abdominal wall. However, rupture into the duodenum is very rare[4]. Furthermore, no reports of upper gastrointestinal bleeding caused by pseudocyst rupture in patients under anticoagulation therapy for venous thrombosis associated with acute pancreatitis have been published.

We describe herein a very rare and unique case of massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to pancreatic pseudocyst rupture into the duodenum, which developed during anticoagulation therapy for portal vein thrombosis associated with acute pancreatitis.

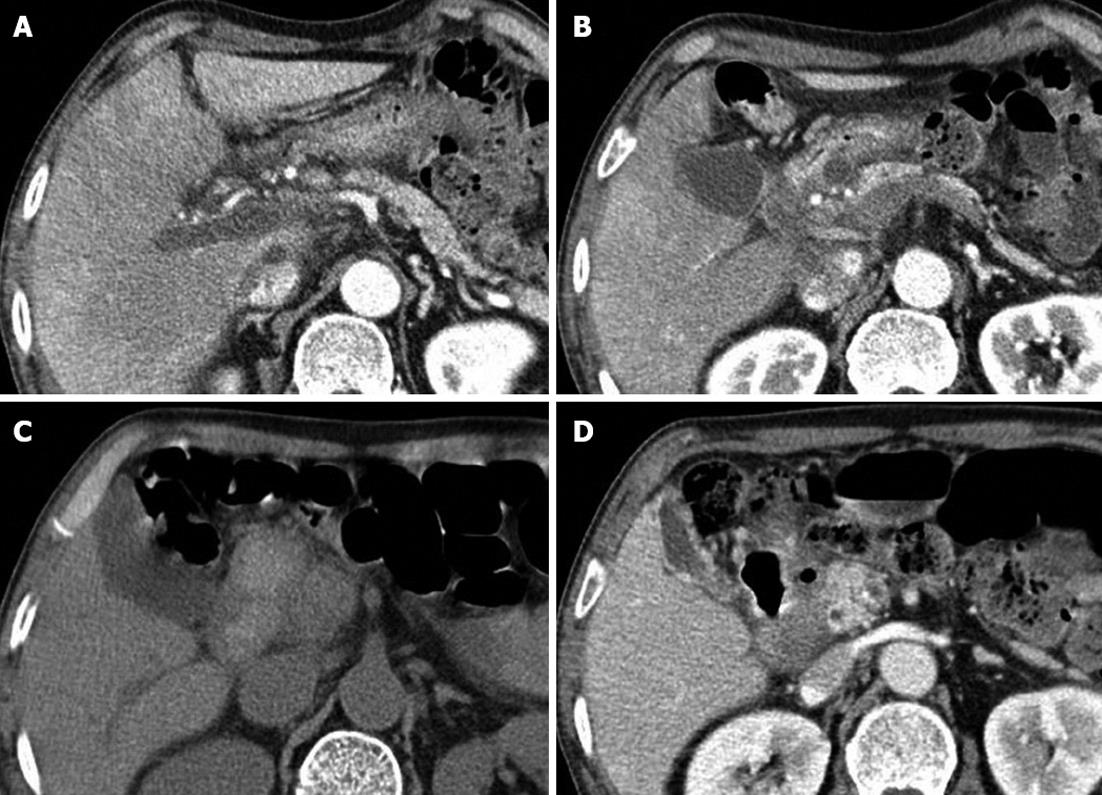

A 73-year-old man was transferred to our emergency department for the management of massive hematemesis. On arrival, his systolic blood pressure was 70 mmHg, and his blood hemoglobin level was 6.8 g/dL. He received a transfusion of two units of packed red blood cells. Seven weeks prior, he had initially developed acute alcoholic pancreatitis, and one month prior, he had been diagnosed with acute progressive portal vein thrombosis associated with non-necrotizing acute alcoholic pancreatitis. Since then, he had been receiving anticoagulation therapy. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the abdomen revealed not only thrombosis of the portal vein trunk but also thrombosis of the right and left portal veins (Figure 1A), and low perfusion areas were diffusely observed on the liver parenchyma. A 12 mm × 10 mm cystic lesion was found, suggesting the presence of a pancreatic pseudocyst and extensive fluid collection around the pancreatic head (Figure 1B). Endoscopic ultrasonography also demonstrated the absence of a color Doppler signal and thrombosis of the portal vein, superior mesenteric vein, and distal splenic vein. Arterial portography confirmed an occlusion and thrombosis of the portal vein, superior mesenteric vein, and distal splenic vein. The factors indicating a coagulation defect and tumor markers were normal. We decided to perform anticoagulation therapy because the patient complained of abdominal pain, and serial CT scans showed the progression of the acute portal vein thrombosis. He was treated with intravenous heparin and then switched to warfarin.

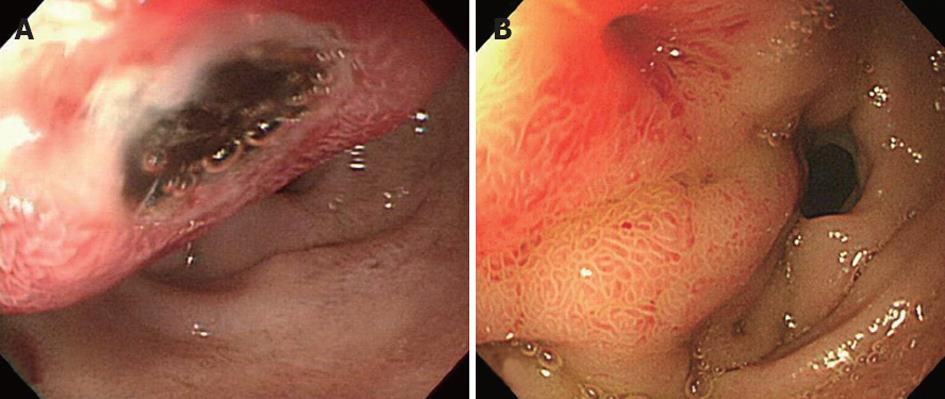

Endoscopy and abdominal CT scans were performed to evaluate the hematemesis. Emergency endoscopy (Figure 2A) revealed a 2 cm submucosal tumor-like lesion located just distal to the pylorus. The mucosa showed a central ulceration covered with dark blood clots, which was suggested as a cause of the upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Abdominal CT scans (Figure 1C) revealed a large, walled-in fluid collection of high attenuation around the pancreatic head, indicating a hemorrhagic pseudocyst of the pancreatic head that caused the displacement of the duodenum.

The patient was treated with a high dose of pantoprazole, a proton pump inhibitor, and the warfarin medication was stopped. The patient was hemodynamically stabilized, and no recurrent bleeding occurred. On the seventh day following admission, follow-up endoscopy (Figure 2B) revealed a reduction of the bulging lesion and a fistula opening with clear discharge, which was suspected to be pancreatic fluid. A follow-up abdominal CT scan (Figure 1D) showed a small collapsed cyst without internal hematoma, and a fistulous tract was also observed between the duodenum and the pseudocyst, resulting in air pocket in the cyst. After only conservative treatment, the patient recovered without recurrent bleeding and was discharged without warfarin medication.

Pancreatitis may cause a spectrum of venous and arterial vascular complications. Of these complications, venous thromboses are typically reported in the splenic vein and less commonly in the superior mesenteric vein or portal vein[5]. Thrombotic complications have been known to be more common in alcohol-induced, necrotizing, and chronic pancreatitis[6,7]. It has been suggested that the pathogenesis of venous thromboses involves stasis, spasm, and mass effects from the surrounding inflamed pancreas and direct damage of the venous wall by liberated enzymes[5]. Our case was associated with non-necrotizing, alcoholic pancreatitis. The portal vein was mainly involved, although venous thromboses also occurred in the distal splenic vein and superior mesenteric vein.

Specific therapeutic management for portal vein thrombosis seems to be mandatory to resolve portal vein obstruction, thereby preventing the development of chronic portal vein thrombosis and avoiding serious complications, such as portal vein hypertension, mesenteric ischemia, and infarction[2,3]. However, randomized controlled studies on the efficacies of most forms of therapy for portal vein thrombosis are lacking. The use of unfractionated heparin, with subsequent transition to oral warfarin is the most common approach to anticoagulation[2], while Gonzelez et al[8] recently reported that recanalization is observed in almost one third of patients, irrespective of whether they receive systemic anticoagulation. The issue of warfarin dose has not been addressed in randomized trials, and the optimal duration of anticoagulation is controversial[2]. What is certain is that the sooner the treatment is given, the better the outcome will be; the rate of recanalization is approximately 69% if anticoagulation is initiated within the first week after diagnosis, while it falls to 25% when initiated during the second week[3].

In our case, anticoagulation therapy was not started at an earlier stage of portal venous thrombosis but began after the confirmation of thrombotic progression, which could explain why the patient achieved only partial portal vein recanalization. Fortunately, the patient did not develop mesenteric ischemia or infarction, and the portal vein thrombosis did not worsen further.

Gastrointestinal bleeding in the setting of pancreatitis arises from vascular complications or coexisting lesions[9,10]. Major gastrointestinal bleeding is considered to be rare, but its exact incidence is not well established. According to a recent report of 1356 acute pancreatitis patients, spontaneous bleeding occurred in 10 patients, and 6 patients had gastrointestinal bleeding[10]. The most frequent cause of severe bleeding in pancreatitis is a ruptured pseudoaneurysm, which accounts for approximately 60% of cases, and a hemorrhagic pseudocyst without a pseudoaneurysm and a capillary, venous, or small vessel hemorrhage each account for approximately 20% of cases[7,11]. In a review of cases from 1987 to 1996, 31 patients were found to have developed vascular lesions either in the form of hemorrhage into a pseudocyst (12 patients) or pseudoaneurysms (19 patients)[12].

In the management of any hemorrhage, the early recognition and investigation of hemorrhagic episodes is imperative because accurate diagnosis and timely radiological interventional procedures can reduce mortality[7]. Dynamic bolus CT and angiography are considered to be the most useful means of finding a hemorrhage[13]. In particular, angiography can play an invaluable role both in locating the source of bleeding and in the embolization of the bleeding vessel[14]. In the present case, the diagnosis of a ruptured bleeding pseudocyst was made with CT scans and endoscopy, and the ruptured bleeding pseudocyst confirmed the presence of the fistula tract and the walled-in fluid collection with high attenuation around the pancreatic head, providing evidence supportive of a bleeding pseudocyst. Due to the hemodynamically stable clinical conditions and no evidence of pseudoaneurysm formation on CT scans, we did not perform angiography or surgical therapy and decided to pursue a “watchful waiting” policy.

The rupture of a pseudocyst into the gastrointestinal tract either results in no symptoms or leads to melena or hematemesis that typically requires urgent measures[15]. Although rupture into the surrounding viscera is a well-known phenomenon, the spontaneous rupture of a pseudocyst into the upper gastrointestinal tract is very rarely reported[4,16-21], and the spontaneous rupture of a pseudocyst into the duodenum most frequently occurs in the second portion of the duodenum[21]. In the presented case, the first part of the duodenum was involved, and rupture into the duodenum led to hematemesis requiring transfusion.

In our case, the exact pathogenic mechanisms of the bleeding and rupture of the pancreatic pseudocysts were unclear. However, we can suggest some possibilities as to why massive bleeding due to pseudocyst rupture occurred. First, the pseudocyst may have been tensely distended because of intra-cystic bleeding caused by warfarin use and eventually ruptured into the duodenum; Second, the rupture of the pancreatic pseudocyst could have developed first, and severe bleeding of the ruptured duodenal mucosa followed due to the anticoagulation therapy. Consequently, we considered that the warfarin either initiated or aggravated the bleeding into the duodenum. Finally, in this case, it was not clear whether portal hypertension by portal vein thrombosis affected the bleeding risk itself and its severity.

In conclusion, we report a rare case of massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to pancreatic pseudocyst rupture into the duodenum, which developed during anticoagulation therapy for acute pancreatitis associated with portal vein thrombosis. Gastroenterologists should consider a pseudocyst rupture into the gastrointestinal tract as a bleeding source in patients with pancreatitis and should also keep in mind that anticoagulants used to manage portal vein thrombosis associated with acute pancreatitis can lead to serious bleeding.

Peer reviewer: Ibrahim A Al Mofleh, Professor, Deaprtment of Medicine, College of Medicine, King Saud University, PO Box 2925, Riyadh 11461, Saudi Arabia

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Vujic I. Vascular complications of pancreatitis. Radiol Clin North Am. 1989;27:81-91. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Parikh S, Shah R, Kapoor P. Portal vein thrombosis. Am J Med. 2010;123:111-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ponziani FR, Zocco MA, Campanale C, Rinninella E, Tortora A, Di Maurizio L, Bombardieri G, De Cristofaro R, De Gaetano AM, Landolfi R. Portal vein thrombosis: insight into physiopathology, diagnosis, and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:143-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Muckart DJ, Bade P. Pancreatic pseudocyst haemorrhage presenting as a bleeding duodenal ulcer. Postgrad Med J. 1989;65:748-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mortelé KJ, Mergo PJ, Taylor HM, Wiesner W, Cantisani V, Ernst MD, Kalantari BN, Ros PR. Peripancreatic vascular abnormalities complicating acute pancreatitis: contrast-enhanced helical CT findings. Eur J Radiol. 2004;52:67-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dörffel T, Wruck T, Rückert RI, Romaniuk P, Dörffel Q, Wermke W. Vascular complications in acute pancreatitis assessed by color duplex ultrasonography. Pancreas. 2000;21:126-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mendelson RM, Anderson J, Marshall M, Ramsay D. Vascular complications of pancreatitis. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:1073-1079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Gonzelez HJ, Sahay SJ, Samadi B, Davidson BR, Rahman SH. Splanchnic vein thrombosis in severe acute pancreatitis: a 2-year, single-institution experience. HPB (Oxford). 2011;13:860-864. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Andersson E, Ansari D, Andersson R. Major haemorrhagic complications of acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1379-1384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Balthazar EJ. Complications of acute pancreatitis: clinical and CT evaluation. Radiol Clin North Am. 2002;40:1211-1227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nehéz L, Tihanyi TF, Hüttl K, Winternitz T, Harsányi L, Magyar A, Flautner L. Multimodality treatment of pancreatic pseudoaneurisms. Acta Chir Hung. 1997;36:251-253. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Urakami A, Tsunoda T, Kubozoe T, Takeo T, Yamashita K, Imai H. Rupture of a bleeding pancreatic pseudocyst into the stomach. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:383-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gambiez LP, Ernst OJ, Merlier OA, Porte HL, Chambon JP, Quandalle PA. Arterial embolization for bleeding pseudocysts complicating chronic pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 1997;132:1016-1021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Habashi S, Draganov PV. Pancreatic pseudocyst. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:38-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 16. | Krejcí T, Hoch J, Leffler J. Massive hemorrhage from a pancreatic pseudocyst into the duodenum. Rozhl Chir. 2003;82:413-417. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Hiraishi H, Terano A. Images in clinical medicine. Rupture of a pancreatic pseudocyst into the duodenum. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kobayashi H, Itoh T, Shima N, Kudoh T, Shibuya K, Maekawa T, Kogawa K, Konishi J. Periduodenal panniculitis due to spontaneous rupture of a pancreatic pseudocyst into the duodenum. Abdom Imaging. 1995;20:106-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Willard MR, Shaffer HA, Read ME. Resolution of a pancreatic pseudocyst by spontaneous rupture into the duodenum. South Med J. 1982;75:618-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bretholz A, Lämmli J, Corrodi P, Knoblauch M. Ruptured pancreatic pseudocysts: diagnosis by endoscopy. Report of 3 cases. Endoscopy. 1978;10:19-23. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Bellon EM, George CR, Schreiber H, Marshall JB. Pancreatic pseudocysts of the duodenum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;133:827-831. [PubMed] |