Published online Oct 14, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i38.5324

Revised: August 13, 2012

Accepted: August 16, 2012

Published online: October 14, 2012

Reports of magnet ingestion are increasing rapidly globally. However, multiple magnet ingestion, the subsequent potential complications and the importance of the early identification and proper management remain both under-recognized and underestimated. Published literature on such cases could possibly represent only the tip of an iceberg with press reports, web blogs and government documents highlighting further occurrence of many more such incidents. The increasing number of complications worldwide being reported secondary to magnet ingestion point not only to an acute lack of awareness about this condition among the medical profession but also among parents and carers who will be in most cases the first to pick up on magnet ingestion. There still seems to be no consensus on the management of magnet ingestion with several algorithms being proposed for management. Prevention of this condition remains a much better option than cure. Proper education and improved awareness among parents and carers and frontline medical staff is key in addressing this rapidly emerging problem. The goal of managing such cases of suspected magnet ingestion should be aimed at reducing delays between ingestion time, diagnosis time and intervention time.

- Citation: George AT, Motiwale S. Magnets, children and the bowel: A dangerous attraction? World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(38): 5324-5328

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i38/5324.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i38.5324

Ingestion of foreign bodies is a common clinical problem; the occurrence of which has been steadily increasing all over the world. More than three quarters of such cases occur in children[1]. Of particular concern is the diagnostic and management dilemma that is posed by the ingestion of magnetic elements. Ingestion of a confirmed single magnet by itself does not pose a problem because it behaves just as an isolated foreign body. The single magnet in most cases moves through the gut harmlessly and silently and usually gets expelled without complications[2,3]. However, the ingestion of multiple magnets or a single magnet along with another metallic piece poses a totally different challenge as these magnetic elements can get attracted to each other with forces up to 1300 G[4] and any intervening bowel wall between the attracted parts eventually undergoing pressure necrosis. Subsequent fistulization between bowel loops can remain silent until it leaks and peritonitis intervenes.

The issues of foreign body ingestion have been well discussed in the literature. However, multiple magnet ingestion, the subsequent potential complications and the importance of the early identification and proper management remain both under-recognized and underestimated. Reports of multiple magnet ingestion and its complications have been steadily increasing over the past few years, with over 15 cases being reported in the literature over 7 mo in 2012 compared to 10 cases in 2010, and two cases per year about a decade ago[3,5-8]. Published literature on such cases may represent only the tip of an iceberg with press reports, web blogs and government documents highlighting further occurrence of many more such incidents[5]. The extent of the problem is highlighted as a total of 128 published cases across 18 countries assimilated in 2010 have now expanded to over 150 cases over 22 countries in 2012[6-10]. The majority of such cases have involved the ingestion of either two or three magnetic elements, although there is one reported case of nearly 100 pieces[11].

Initial reports of this condition more than a decade ago were mainly confined to infants and toddlers. Children with a variety of psychological conditions including autism, developmental delays, history of pica, schizoid characteristics, Angelman syndrome, behavioral problems, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome with developmental delays, 4p syndrome, congenital hydrocephalus, mental retardation, reactive attachment, and anxiety were thought to be at a higher risk for accidental ingestion[11]. Of interest was the fact that this group comprised < 15% of the total cases reported so far.

Presently, the incidence of this problem no longer remains confined to these groups. Recent reports suggest that multiple magnet ingestion seem to be occurring with increasing frequency in fully developed older age groups[5,11,12].

The origin of most of these magnetic elements has been traced to toys, either directly belonging to the child or to an elder sibling[9,11-13]. A possible cause for the increase of such cases is the easy availability of cheap toys that contain magnetic elements[14]. New-generation magnets are made of combinations containing iron, along with other rare earth elements including boron and neodymium, and such magnets tend to be nearly 10 times stronger than standard iron magnets. This has enabled the miniaturization of magnets for inclusion in various small toys[3,15]. In many of these toys, the magnetic elements are poorly embedded in plastic moulds from which they can easily become detached[16].

The key to diagnosis is to obtain a reliable history of magnet ingestion. A credible history of ingestion is crucial in the early recognition and correct management of this condition. The lack of a documented history of ingestion in nearly half of the reported cases even among the older age groups is of concern[5]. Younger children or those with developmental delays may be hindered by their inability to communicate effectively to their parents due to their limited linguistic or developmental abilities. Older children may hesitate to inform parents due to a sense of guilt or embarrassment or a fear of the consequences[9,17]. This may have a direct bearing on the time interval between ingestion and intervention. This may be shorter if there is evidence of ingestion or longer when only the occurrence of bowel complications may highlight an underlying magnetic pathology. Time intervals between ingestion and intervention have varied from a few hours to a few months[5].

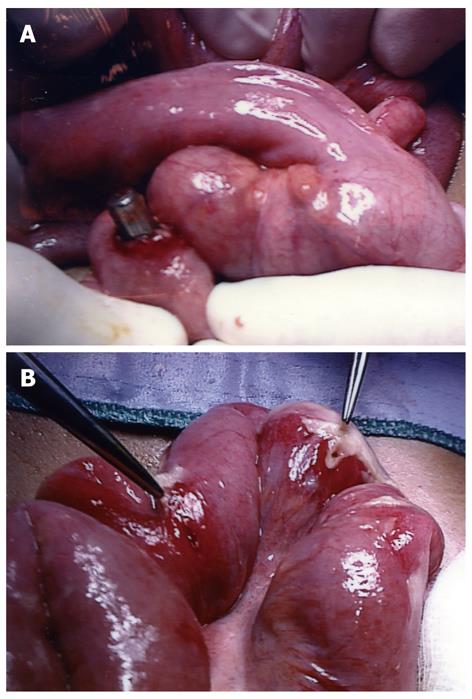

Symptoms may vary from totally asymptomatic or an unrelated pain to a mild flu-like illness with nonspecific symptoms of nausea, vomiting, cramps, or abdominal pain to features of bowel obstruction or localized peritonitis[3,5,12,18] (Figure 1A, B).

Plain abdominal radiographs almost always pick up these objects and is a simple and quick screening test if a history of ingestion is obtained[19-21]. Plain radiography is a sensitive tool to screen and identify such cases but is poor in differentiating whether the ingested magnet is truly only single or is actually composed of multiple densely adherent magnetic elements. Although radiographs can be taken at different angles and planes, the differences in radiographic appearances between a single magnet and multiple magnets adhered to each other may be subtle and impossible to differentiate[2]. Subtle separations or gaps between otherwise individual metallic pieces may point to the presence of multiple magnetic elements or the presence of intervening bowel between the magnets. However, this is by no means diagnostic and the absence of any gaps within the imaged magnet does not exclude more than one magnet nor the absence of bowel wall involvement[2]. In addition, the failure of the ingested magnetic element to progress through the bowel on subsequent follow-up radiographs should raise the suspicion of multiple magnetic elements with entrapped bowel, although this is not diagnostic because the multiple magnets can move en bloc[2,17,22,23]. Documenting the size and shape of the swallowed object on radiography and confirming the presence of only a single magnet may be challenging because such ingested magnets tend to be miniature and they usually originate from children’s toys[3,12].

Computed tomography and ultrasound can be performed but may not contribute greatly because they generally lack the sensitivity to determine the multiplicity of or the presence of trapped bowel between the magnetic objects. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans should not be performed due to the magnetic nature of the ingested foreign body and bowel perforation secondary to inadvertent MRI has been reported[8].

Management of ingested foreign bodies still relies to a great extent on “masterly inactivity”, whereby the ingested foreign body traverses the gut and is expelled without any complications.

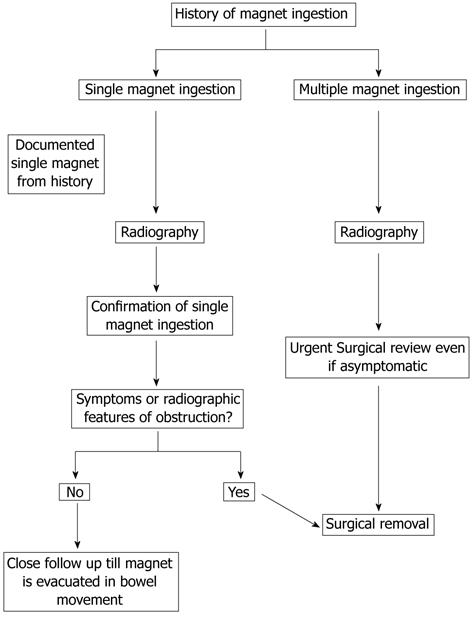

There still seems to be no consensus on the management of magnet ingestion, with several algorithms being proposed[2,3,5,21]. A common underlying theme is that in cases of multiple magnet ingestion, conservative management may have no appreciable role. Surgical exploration and removal remains the preferred management irrespective of the size or shape of the magnet[19].

A diagnostic and management dilemma arises if there is a doubt as to whether one or more magnets were ingested. A proper history is important to help identify between single or multiple magnet ingestion, but reliable documentation of ingestion may not always be present[5]. Clear differentiation is not always possible between the two because multiple magnets may tend to be densely adherent to each other and can mimic a single object on imaging.

Conservatively discharging the child back to the community without reliable evidence of single magnet ingestion may have the potential to cause unnecessary morbidity[3,5]. Undiagnosed multiple magnets can tend to remain asymptomatic for several weeks or months until potentially disastrous complications intervene[5].

Close observation of such cases even if they are asymptomatic may be prudent given the lack of any investigation which can effectively rule out multiple adherent magnets. If single magnet ingestion is suspected, normal progression through the bowel can be monitored closely with expulsion of the magnet through a bowel movement[21].

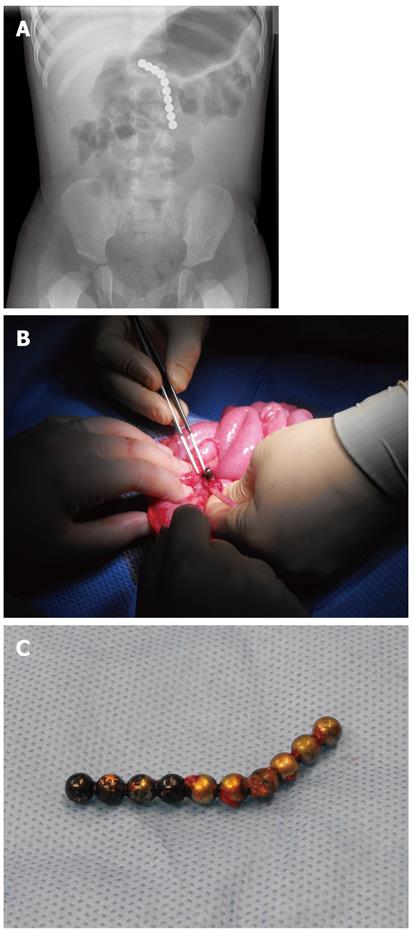

If multiple magnet ingestion is suspected, the entire gastrointestinal tract remains at risk of perforation even if the child is asymptomatic (Figure 2A-C). All such cases should be reviewed urgently by the surgeon with a view to magnet removal. If pediatric surgery expertise is not available, urgent transfer to an appropriate specialist center is important (Figure 3).

The aim of management in cases of suspected multiple magnet ingestion should be to shorten the delays between ingestion time, diagnosis time and intervention time.

Removal of the magnets is seminal and delaying the removal or waiting for evidence of bowel obstruction to develop may lead to unnecessary morbidity and even mortality[3,5]. All such reported cases with the exceptions of a few sporadic cases[11,18] have been managed with the surgical removal of the magnetic parts. Bowel injury following multiple magnet ingestion in a few conservatively managed cases may have been avoided possibly due to a near-simultaneous ingestion of the magnetic elements, which may have then behaved as a single large magnet. This however, would not be sufficient reason to recommend conservative management in such cases.

Removal of the ingested magnets can be retrieved endoscopically if they are in the esophagus, stomach or proximal duodenum[3]. Once the magnets move further into the small bowel, surgical removal either through an exploratory or a laparoscopic assisted laparotomy is required to localize and remove the magnets.

The field of vision regarding this condition is highly myopic. Prevention remains a much better option than cure for this rapidly increasing problem.

The increasing number of complications worldwide being reported secondary to magnet ingestion point not only to an acute lack of awareness about this condition among the medical profession but also among parents and carers who will be, in most cases, the first to pick up on magnet ingestion. Parents need to be alerted to the potential risk of silent bowel perforation and fistulation from accidental ingestion of magnets. The importance of increasing awareness regarding the potential complications of magnet ingestion is crucial. This could prompt parents and carers to identify earlier cases of suspected magnet ingestion and rapidly seek appropriate medical attention, and considerably reduce the delay between ingestion and diagnosis.

There also exists a lack of awareness among the medical profession about the potential of multiple magnet ingestion to do great harm. Improving awareness among frontline medical staff can help to reduce the time delay between ingestion and diagnosis, as well as between diagnosis and intervention.

There is also a need for tighter control and regulation of toys with magnetic components. Since 2006, there have been numerous alerts and recalls from Canadian and United States consumer product safety commissions issued in relation to children and the sale of toys with small ingestible magnetic parts[2,24]. The occurrence of such cases from over 21 countries worldwide highlights that this is no longer confined to a localized geographical region or population. Toy manufacturers all over the world can incorporate easily visible warnings regarding the presence of small magnetic parts in the toys on the labels. Highlighting age restriction on toys may not by itself cover much ground without improved awareness because younger children can accidentally ingest magnetic elements from toys that may have been appropriately bought for elder siblings in the family.

Parents, carers and medical staff globally remain under-informed and largely unaware regarding this rapidly increasing potential public health problem. The goal of managing such cases of suspected magnet ingestion should be to reduce the delays between ingestion time, diagnosis time and intervention time.

Peer reviewers: Martin D Zielinski, MD, Department of Trauma, Critical Care and General Surgery, Mayo Clinic, 1216 2nd St Sw, Rochester, MN 55902, United States; Ferruccio Bonino, MD, PhD, Professor of Gastroenterology, Director of General Medicine 2 Unit, Director of Liver and Digestive Disease Division, Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital of Pisa, University of Pisa, Via Roma 67, 56124 Pisa, Italy; Andrzej S Tarnawski, MD, PhD, DSc (Med), Professor of Medicine, Chief Gastroenterology, VA Long Beach Health Care System, University of California, Irvine, CA, 5901 E. Seventh Str., Long Beach, CA 90822, United States

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Hebra ATE. Esophagoscopy and Esophageal Foreign Bodies. Operative Pediatric Surgery. 1st ed. New York: Mc Graw-Hill 2003; 331-339. |

| 2. | Butterworth J, Feltis B. Toy magnet ingestion in children: revising the algorithm. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:e3-e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tavarez MM, Saladino RA, Gaines BA, Manole MD. Prevalence, Clinical Features and Management of Pediatric Magnetic Foreign Body Ingestions. J Emerg Med. 2012;Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Honzumi M, Shigemori C, Ito H, Mohri Y, Urata H, Yamamoto T. An intestinal fistula in a 3-year-old child caused by the ingestion of magnets: report of a case. Surg Today. 1995;25:552-553. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Naji H, Isacson D, Svensson JF, Wester T. Bowel injuries caused by ingestion of multiple magnets in children: a growing hazard. Pediatr Surg Int. 2012;28:367-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chandra S, Hiremath G, Kim S, Enav B. Magnet ingestion in children and teenagers: an emerging health concern for pediatricians and pediatric subspecialists. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Brown JC, Murray KF, Javid PJ. Hidden attraction: a menacing meal of magnets and batteries. J Emerg Med. 2012;43:266-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Baines H, Saenz NC, Dory C, Marchese SM, Bernard-Stover L. Magnet-associated intestinal perforation results in a new institutional policy of ferromagnetic screening prior to MRI. Pediatr Radiol. 2012;Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | M Swaminathan RB, Scott D. Injuries due to Magnets in Children: An Emerging Hazard. 1 st ed. Queensland: Government of Queensland 2010; 1-10. |

| 10. | Salimi A, Kooraki S, Esfahani SA, Mehdizadeh M. Multiple magnet ingestion: is there a role for early surgical intervention? Ann Saudi Med. 2012;32:93-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Oestreich AE. Worldwide survey of damage from swallowing multiple magnets. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39:142-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | George AT, Motiwale S. Magnet ingestion in children--a potentially sticky issue? Lancet. 2012;379:2341-2342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liu SQ, Lei P, Lv Y, Wang SP, Yan XP, Ma HJ, Ma J. [Systematic review of gastrointestinal injury caused by magnetic foreign body ingestions in children and adolescence]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Zazhi. 2011;14:756-761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lee KJ, Kim CW, Choe JW, Kim SE, Lee SJ, Oh JH, Park YS. Intestinal perforation caused by three small magnets. Eur J Emerg Med. 2009;16:228-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | McCormick S, Brennan P, Yassa J, Shawis R. Children and mini-magnets: an almost fatal attraction. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:71-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Oh HK, Ha HK, Shin R, Ryoo SB, Choe EK, Park KJ. Jejuno-jejunal fistula induced by magnetic necklace ingestion. J Korean Surg Soc. 2012;82:394-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kircher MF, Milla S, Callahan MJ. Ingestion of magnetic foreign bodies causing multiple bowel perforations. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:933-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shastri N, Leys C, Fowler M, Conners GP. Pediatric button battery and small magnet coingestion: two cases with different outcomes. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27:642-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lee BK, Ryu HH, Moon JM, Jeung KW. Bowel perforations induced by multiple magnet ingestion. Emerg Med Australas. 2010;22:189-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wong HH, Phillips BA. Opposites attract: a case of magnet ingestion. CJEM. 2009;11:493-495. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Hussain SZ, Bousvaros A, Gilger M, Mamula P, Gupta S, Kramer R, Noel RA. Management of ingested magnets in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:239-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shah SK, Tieu KK, Tsao K. Intestinal complications of magnet ingestion in children from the pediatric surgery perspective. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2009;19:334-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dutta S, Barzin A. Multiple magnet ingestion as a source of severe gastrointestinal complications requiring surgical intervention. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:123-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Gastrointestinal injuries from magnet ingestion in children--United States, 2003-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:1296-1300. [PubMed] |