Published online Sep 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i35.4959

Revised: July 4, 2012

Accepted: August 4, 2012

Published online: September 21, 2012

Cameron lesions represent linear gastric erosions and ulcers on the crests of mucosal folds in the distal neck of a hiatal hernia (HH). Such lesions may be found in upto 50% of endoscopies performed for another indication. Though typically asymptomatic, these may rarely present as acute, severe upper gastrointestinal bleed (GIB). The aim is to report a case of a non-anemic 87-year-old female with history of HH and atrial fibrillation who presented with hematemesis and melena resulting in hypovolemic shock. Repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy was required to identify multiple Cameron ulcers as the source. Endoscopy in a patient with HH should involve meticulous visualization of hernia neck and surrounding mucosa. Cameron ulcers should be considered in all patients with severe, acute GIB and especially in those with known HH with or without chronic anemia.

- Citation: Kapadia S, Jagroop S, Kumar A. Cameron ulcers: An atypical source for a massive upper gastrointestinal bleed. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(35): 4959-4961

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i35/4959.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i35.4959

The incidence of hiatal hernia (HH) rises with age[1]. Given the rising demographics and the growing number of endoscopies, this condition now constitutes an increasingly common endoscopic finding. One study reported the incidence to be upwards of 50% during upper endoscopies performed for another indication[2]. Though typically asymptomatic, several complications can occur including gastroesophageal reflux disease[3], iron deficiency anemia[4], acute or chronic bleeding[5], and ulcer or erosion formation[2]. Usually an incidental endoscopic finding, Cameron lesions represent linear gastric erosions and ulcers on the crests of mucosal folds in the distal neck of a HH. Both erosions and ulcers are thought to be distinct forms of the same disease process. Lesions are found in 5.2% of patients with HH identified on upper endoscopy[6] and in over 60%, multiple lesions may be found[1].

An 87-year-old female presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with several episodes of bright red hematemesis and black, tarry stools over six hours. She complained of severe lightheadedness and crampy, lower abdominal pain. On examination, she was found to be hypotensive with systolic blood pressures in the 60s, and despite aggressive resuscitation with intravenous fluids and blood products, she required vasopressors.

Two days earlier, she had been discharged following a brief hospital stay for atrial fibrillation and a large HH. She had been conservatively treated with proton pump inhibitor, Sucralfate, and Ondansetron as needed with fair results.

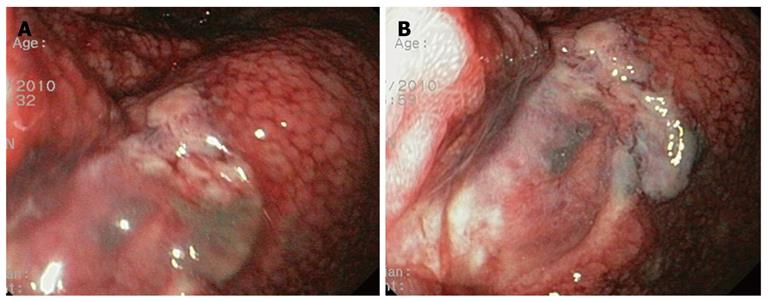

At this presentation, hemoglobin (Hgb) was 12.7 g/dL (baseline of 14.8 g/dL). Nasogastric lavage returned 500 cc of bright red blood. Intravenous proton pump inhibitor was started, patient was intubated and an emergent EGD revealed a large clot in the gastric fundus along with diffuse, friable mucosa in the mid-distal esophagus. No other bleeding site was identified. Despite multiple units of packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma, the patient’s hemoglobin continued to decline. A repeat EGD demonstrated multiple circumferential non-bleeding Cameron ulcers at 37 cm with large placental clots in the fundus (Figure 1). Small clots were also seen at the gastroesophageal junction. In total, the patient received 14 units of packed red blood cells, multiple units of fresh frozen plasma, protamine sulfate and Vitamin K. Her Hgb stabilized on hospital day 10. During the course, she developed aspiration pneumonia, which was successfully treated with antibiotics. No further bleeding occurred and the patient recovered.

The pathogenesis of Cameron lesions is poorly understood. Some attribute lesion formation to mechanical trauma to the esophagus caused by respiration-related diaphragmatic contractions[6]. Other etiological factors may include acid reflux, ischemia, Helicobacter pylori infection, gastric stasis or vascular stasis[7]. It is likely that the etiology is multifactorial, and includes genotype, phenotype and patient risk factors including underlying co-morbidities and medication use. The prevalence is also likely dependent on the size of the HH with a 10%-20% risk for Cameron ulcers in hernias 5 cm in size or greater[8]. However, the absence of HH should not rule out Cameron lesions either. One study used push enteroscopy to evaluate ninety-five patients with obscure GIB previously investigated with standard endoscopy. Of the thirty-nine patients with an identifiable source, Cameron lesions were the second most commonly missed lesion (21%)[9]. Presumably, the lack of a large HH may have reduced the suspicion for Cameron lesions. Among the most concerning clinical manifestations of Cameron lesions are acute and chronic GIB. Chronic blood loss resulting in anemia has been well described. A large prospective, national, population-based study found that patients with HH had a significantly higher association of iron-deficiency anemia as compared to those with esophagitis[4]. Additionally, in a case-controlled study, Cameron showed that of 259 patients with radiographic evidence of HH, 18 were anemic compared to 1 in the control group (P < 0.001)[10]. Patients with Cameron lesions typically respond well to medical treatment consisting of iron supplementation with or without acid-suppression therapy. It is worth noting that our patient’s MCV was 97 on admission without any supplementation.

More alarming are lesions that present as severe, acute GIB. Studies have reported rates of 29%-58%, raising the possibility of life-threatening hemorrhage[2,10]. To our knowledge, there are very few reports of life-threatening upper GIB secondary to a Cameron ulcer. One case report describes the successful treatment of a visible vessel within a Cameron ulcer with band ligation[11]. However, in these cases, surgical intervention is recommended, as endoscopic hemostasis can be technically difficult. Potential risks of endoscopy in acute, upper GIB include deep ulcers and perforation as the gastrointestinal wall around the gastroesophageal junction lacks fibrous tissue. Thus, surgery should be considered in those with either severe sliding hernias with Cameron lesions and in patients with lesion-related complications refractory to medical treatment[12]. Long-term recurrence rates are extremely low following surgery[13].

Complicating our case was the need to anticoagulate the patient for atrial fibrillation prior to endoscopy. More studies are needed to evaluate whether radiographic evidence of large HH should prompt an endoscopy prior to anticoagulation. In conclusion, endoscopy in a patient with radiographic evidence of large HH should involve meticulous antegrade and retrograde visualization with views of hernia neck and surrounding mucosa. Cameron ulcers are a potential source of severe, acute GIB in patients with known HH with or without chronic anemia.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Sheng Li, Shandong Tumor Hospital, Jinan 250117, Shandong Province, China

S- Editor Shi ZF L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Sleisenger MH, Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ. Sleisenger and Fordtran's gastrointestinal and liver disease: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, management. 9th ed. Philadelphia , PA: Saunders, Elsevier 2010; 381-383, 710. |

| 2. | Weston AP. Hiatal hernia with cameron ulcers and erosions. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1996;6:671-679. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Hyun JJ, Bak YT. Clinical significance of hiatal hernia. Gut Liver. 2011;5:267-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Relationship of iron-deficiency anemia with esophagitis and hiatal hernia: hospital findings from a prospective, population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:322-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Simić A, Radovanović N, Kotarac M, Gligorijević M, Skrobić O, Konstantinović V, Pesko P. [Hiatal hernia of the esophagus and GERD as a cause of hemorrhage]. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2007;54:135-138. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Cameron AJ, Higgins JA. Linear gastric erosion. A lesion associated with large diaphragmatic hernia and chronic blood loss anemia. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:338-342. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Moskovitz M, Fadden R, Min T, Jansma D, Gavaler J. Large hiatal hernias, anemia, and linear gastric erosion: studies of etiology and medical therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:622-626. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Nguyen N, Tam W, Kimber R, Roberts-Thomson IC. Gastrointestinal: Cameron's erosions. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zaman A, Katon RM. Push enteroscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding yields a high incidence of proximal lesions within reach of a standard endoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:372-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cameron AJ. Incidence of iron deficiency anemia in patients with large diaphragmatic hernia. A controlled study. Mayo Clin Proc. 1976;51:767-769. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Lin CC, Chen TH, Ho WC, Chen TY. Endoscopic treatment of a Cameron lesion presenting as life-threatening gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:423-424. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Moschos J, Pilpilidis I, Kadis S, Antonopoulos Z, Paikos D, Tzilves D, Katsos I, Tarpagos A. Cameron lesion and its laparoscopic management. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2005;24:163. [PubMed] |