Published online Sep 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i35.4885

Revised: July 24, 2012

Accepted: August 14, 2012

Published online: September 21, 2012

AIM: To investigate usefulness of adherence to gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) guideline established by the Spanish Association of Gastroenterology.

METHODS: Prospective, observational and multicentre study of 301 patients with typical symptoms of GERD who should be managed in accordance with guidelines and were attended by gastroenterologists in daily practice. Patients (aged > 18 years) were eligible for inclusion if they had typical symptoms of GERD (heartburn and/or acid regurgitation) as the major complaint in the presence or absence of accompanying atypical symptoms, such as dyspeptic symptoms and/or supraesophageal symptoms. Diagnostic and therapeutic decisions should be made based on specific recommendations of the Spanish clinical practice guideline for GERD which is a widely disseminated and well known instrument among Spanish in digestive disease specialists.

RESULTS: Endoscopy was indicated in 123 (41%) patients: 50 with alarm symptoms, 32 with age > 50 years without alarm symptom. Seventy-two patients (58.5%) had esophagitis (grade A, 23, grade B, 28, grade C, 18, grade D, 3). In the presence of alarm symptoms, endoscopy was indicated consistently with recommendations in 98% of cases. However, in the absence of alarm symptoms, endoscopy was indicated in 33% of patients > 50 years (not recommended by the guideline). Adherence for proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) therapy was 80%, but doses prescribed were lower (half) in 5% of cases and higher (double) in 15%. Adherence regarding duration of PPI therapy was 69%; duration was shorter than recommended in 1% (4 wk in esophagitis grades C-D) or longer in 30% (8 wk in esophagitis grades A-B or in patients without endoscopy). Treatment response was higher when PPI doses were consistent with guidelines, although differences were not significant (95% vs 85%).

CONCLUSION: GERD guideline compliance was quite good although endoscopy was over indicated in patients > 50 years without alarm symptoms; PPIs were prescribed at higher doses and longer duration.

- Citation: Mearin F, Ponce J, Ponce M, Balboa A, González MA, Zapardiel J. Clinical usefulness of adherence to gastro-esophageal reflux disease guideline by Spanish gastroenterologists. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(35): 4885-4891

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i35/4885.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i35.4885

Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most prevalent gastrointestinal disorders in the general population[1]. GERD diagnosis is made mainly according to the presence of symptoms. Patients with heartburn and/or regurgitation (typical GERD symptoms) received the diagnosis. Typical symptoms of GERD are experienced by 25% of people at least once a month, 12% at least once per week, and 5% describe daily symptoms[2]. The prevalence of GERD among the Spanish population is 15%, with 33% and 22% of subjects reporting monthly episodes of heartburn and regurgitation, respectively[3]. Reported consultation rates range from 5% to 56%[4].

GERD is perceived as a benign disease but the spectrum of chronicity and severity of upper gastrointestinal symptoms frequently affects health-related quality of life (HRQoL)[5]. The wide-ranging effects of GERD on health and well-being can have consequences for the work productivity, psychological and social performance of affected individuals, particularly in patients with severe symptoms or night time acid reflux and sleep disturbance[5-8]. In some respects the HRQoL burden of these patients is similar to or greater than that observed in patients with conditions such as diabetes, hypertension or coronary heart disease[9,10].

Although treatment with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is satisfactory in many cases and results in cicatrisation of esophagitis when esophagitis is present, complete disappearance of symptoms is difficult to achieve[11]. Nevertheless, in many cases PPI therapy leads to rapid symptom improvement that is associated with a better HRQoL. For example, in a large Italian study, 96% of patients were satisfied with the results of 4 wk of PPI therapy and the average HRQoL score improved significantly during this period[12]. An effective management strategy is particularly important because, as mentioned, GERD imposes a significant burden of illness[13,14]. For that purpose several clinical practice guidelines have been developed by different medical societies and expert consensus meetings[15-19]. However, although many national and international guidelines are currently available, the impact of these recommendations on the behaviour of physicians has generally been limited[20-25]. Only in some disease states guidelines have been shown to influence physician behaviour, which depends on the prevalence of the disorder and access to the guidelines among other factors[26-28].

The objective of this study was to assess the level of adherence of gastroenterologists to the Spanish clinical guidelines for GERD and the results obtained in the care of patients with typical symptoms of GERD attended in daily practice.

This multicentre and observational study was prospectively designed with two purposes: (1) to investigate whether patients with typical GERD symptoms seeking consultation from a specialist in gastroenterology were managed in accordance with the clinical practice guideline for GERD developed by the Spanish Association of Gastroenterology, the Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine and the Iberoamerican Cochrane Center[15]; and (2) to assess the results obtained. The study was focused on the “acute phase” of GERD (4-8 wk after diagnosis) and not on the long-term; therefore, evaluation of maintenance treatment was not done. Thirty-three gastroenterologist from 33 different medical centers throughout Spain participated in the study, that was conducted under routine clinical practice conditions. Gastroenterologists participating in the study were not aware they were included in an adherence study. Consecutive patients were recruited between December 12, 2007 and November 5, 2008. All patients provided written informed consent. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committees of the participating centers.

Consecutive patients (aged > 18 years) attending to gastroenterologists offices were eligible for inclusion if they had typical symptoms of GERD (heartburn and/or acid regurgitation) more than twice a week for at least 2 mo as the major complaint, in the presence or absence of accompanying atypical symptoms, such as dyspeptic symptoms and/or supraesophageal symptoms. All enrolled patients were required to sign the informed consent. Patients who had taken drug treatment for GERD within 2 mo prior to the study were excluded. Also, patients were not eligible they were currently taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or platelet antiaggregant agents as well as if previous treatment with PPIs had been unsuccessful. Patients with history of esophageal or gastric surgery except for suture repair of a perforated gastric ulcer were excluded.

The study protocol included a baseline visit and a final visit, which was scheduled after 4 wk or 8 wk. At the baseline visit, eligibility criteria were assessed and the following data were recorded: demographic and anthropometric variables, and GERD-related symptoms including duration of symptoms, previous drug treatment, and frequency and intensity of typical symptoms. The frequency of each symptom was graded as 0 = absent or present less than 2 d per month, 1 = present more than 2 d per month, 2 = present weekly less than 3 d, and 3 = present 3 or more days per week. Intensity was graded as 0 = none, 1 = awareness of symptom but easily tolerated, 2 = discomfort sufficient to cause interference with normal activities, and 3 = incapacitating, with inability to perform normal activities. The product of frequency and intensity was used to define the severity of each symptom, which was expressed as the absolute number (0-1 = absent or irrelevant, 2 = mild, 3-4 = moderate, 6 = severe, and 9 = very severe).

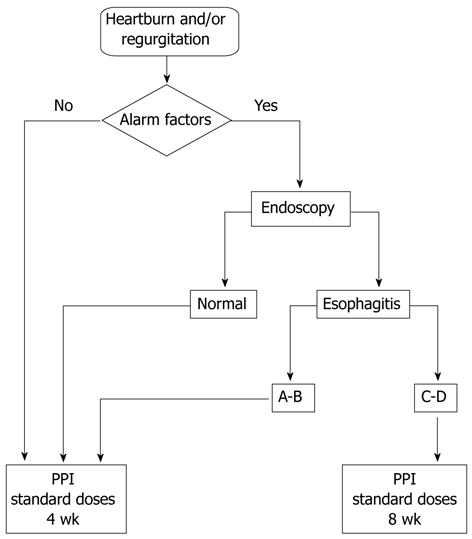

Diagnostic and therapeutic decisions should be made based on specific recommendations of the Spanish clinical practice guideline for GERD[15], which is a widely disseminated and apparently well known instrument among specialists in digestive disease. The algorithm for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with GERD is summarized in the Figure 1. When upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was indicated, reasons and endoscopic findings should be recorded. The presence and severity of erosive esophagitis were determined using the Los Angeles classification[29]. According to the guideline, in the absence of erosive esophagitis or mild esophagitis (Los Angeles grade A or B) the duration of treatment was 4 wk but in the presence of esophagitis grades C and D, the duration of treatment was 8 wk. Treatment-related data included prescription of PPI, dose and duration of treatment (4 wk or 8 wk), and non-pharmacological measures (acid reflux diet, elevated position of the bed). The PPI selection (omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole or esomeprazole) was made by individual medical preference.

Assessments at the end of treatment (4 wk or 8 wk) included frequency and intensity of symptoms to quantify the severity of disease after PPI treatment. Response to treatment was considered when patients became asymptomatic, that is, in the category of “absent or irrelevant”. Patients were interviewed regarding their compliance with treatment, which was classified as excellent (> 95%), very good (> 90%), good (> 80%), fair (≥ 70%), bad (< 70%) and very bad (< 50%).

Sample size calculation was based on proportion of symptomatic treatment response after 4-8 wk. Considering a treatment response around 58%, with a ± 6% deviation, the needed sample size was 260 patients. Expecting a 15% lost during follow-up the final calculated sample size was 306 patients.

Categorical data are expressed as absolute number and percentages, and continuous data as mean and standard deviation. Response to PPI therapy according to adherence to guidelines in the doses prescribed was analyzed with the χ2 test or fisher exact test. All analyses were performed using SAS 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

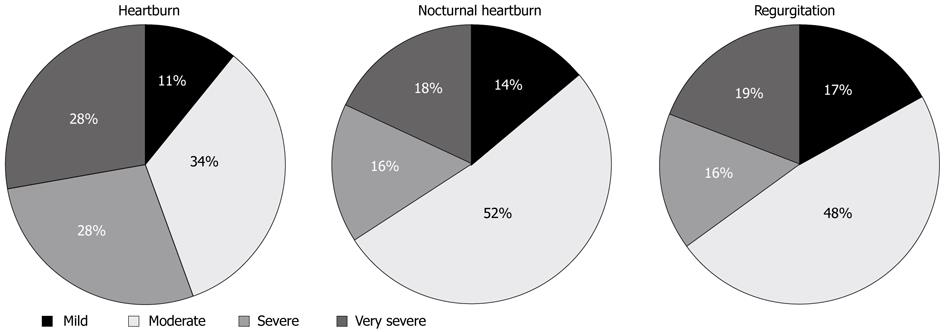

A total of 306 patients were recruited and 301 patients (58.5% men; age of 45 ± 14 years) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the study. All of them completed follow-up. The remaining 5 patients were excluded because of refusal to take part in the study (n = 2) and lack of fulfilment of the inclusion/exclusion criteria (n = 3). Mean time from the onset of GERD symptoms was 4.5 ± 6.3 years. Previous pharmacological treatment for GERD (not within 2 mo prior to the study) was recorded in 156 patients (51.9%), 87 of which had been treated with PPIs. Presenting complaints were heartburn in 99% of cases (nocturnal heartburn in 78%), regurgitation in 86%, and both heartburn and regurgitation in 85%. Only 3 patients complained of regurgitation only. A total of 273 patients (90.7%) presented dyspeptic symptoms and 174 (57.8%) supraesophageal symptoms. Distribution of heartburn, nocturnal heartburn and regurgitation according to severity of symptoms is shown in Figure 2. Symptoms were rated as severe or very severe in 56% of cases for heartburn, 34% for nocturnal heartburn and 35% for regurgitation.

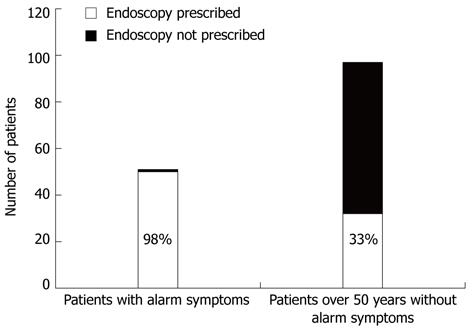

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed in 123 patients (40.8%). According to participating gastroenterologists opinion indication of endoscopy was justified because of alarm symptoms in 50 patients and age over 50 years in 32. Adherence to the guidelines in relation to indication of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was good due to the presence of alarm symptoms in 98% of cases. On the other hand, endoscopy was performed in 32 of 97 patients (33%) older than 50 years of age without alarm symptoms (Figure 3).

Esophagitis was diagnosed in 72 (58.3%) patients (grade A, 23, grade B, 28, grade C, 18, grade D, 3). Metaplastic changes of the esophageal mucosa suggestive of Barrett’s oesophagus were documented in 9 patients and peptic stenosis in 1. Hiatal hernia was reported in 37 patients and Schatzki ring in 5.

Treatment with PPIs was prescribed to 298 patients (99%). In most cases (80%), there was adherence to the guidelines as the recommended dose of PPI was prescribed. However, doses prescribed were lower (half) in 4.8% of cases and higher (double) in 14.7%. The duration of PPI therapy was 4 wk in 63% of cases and 8 wk in 37%. In respect to duration of PPI therapy, adherence to guidelines was shown in 69% of cases (62% for the indication of 4 wk and 7% for 8 wk). Lack of adherence (31% of cases) included duration of treatment of 4 wk in patients with esophagitis grades C-D (0.7%) or 8 wk in patients esophagitis grades A-B (7.8%) or in patients without endoscopic studies (22.8%).

Compliance with pharmacological treatment was excellent in 58% of cases, very good in 30%, good in 8%, fair in 3% and bad or very bad in 1%. Acid reflux disease diet was recommended in 79% of patients and raising the bed position in 34%.

Response to PPI therapy was higher among patients who received PPI doses recommended by the guidelines as compared with patients treated with lower doses (95% vs 85%), although differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.2). Treatment response was similar in patients in which adherence to guidelines regarding duration of treatment was good or poor (95% vs 93%; P = 0.5).

Symptomatic response to treatment according to esophagitis grade was 87% in grade A, 89% in grade B and 100% in grades C and D. The indication to perform an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy had no effect on the rate of response to PPI treatment (P = 0.9) or whether there was good or poor adherence to the guidelines in terms of indication of the endoscopic study (P = 0.7).

GERD is a chronic condition in many cases and frequently requires prolonged therapy. Although complications are infrequent, the symptoms of reflux disease have a profound effect on quality of life and work performance, making GERD an expensive disease to manage. When different management strategies are compared, the cost of each strategy must be balanced against its effectiveness. For that purpose, various clinical practice guidelines have been developed based on the scientific evidence and recommendations made by experts[15-19]. In 2007, the Spanish Association of Gastroenterology, the Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine and the Iberoamerican Cochrane Center developed a clinical practice guideline for GERD, in which two of the authors have collaborated (FM, JP), which was distributed throughout Spain both in printed version and through the Internet[15]. Afterwards, it was investigated whether the GERD guideline had a practical impact through the Spanish gastroenterologists in the care of patients with GERD in routine daily practice.

The main findings of this study can be summarized as follows: (1) upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was requested in 41% of patients, mainly because of the presence of alarm symptoms but also because of age over 50 years without alarm symptoms; (2) severe esophagitis was infrequently diagnosed even though patients were selected for endoscopy; (3) in almost all cases (99%), treatment with PPIs was prescribed, in the majority of cases (80%) in accordance with doses recommended in the guidelines (lower doses were prescribed in only 5% of cases and higher doses in 15%); (4) adherence regarding duration of PPIs therapy was lower (69%) and most non-compliant behaviours were related to prolonged duration of treatment in patients with mild esophagitis or in those in which endoscopy was not performed; and (5) response to PPI treatment was higher in patients treated with doses of PPIs recommended in the clinical practice guidelines as compared with patients receiving other doses, although the difference was not statistically significant (95% vs 85%).

It is to note that, although GERD guideline compliance was quite good, endoscopy was overindicated. Thus, it was prescribed in 32 out of 97 patients (33%) older than 50 years of age without alarm symptoms. We have to emphasize here that not in the Spanish guideline neither in other very prestigious ones[30,31] is endoscopy recommended in patients with typical GERD symptoms (heartburn and/or regurgitation) older than 50 years and no alarm symptoms.

GERD is a very frequent cause of consultation in specialized gastroenterology practices as well as in the primary care setting. Consultation for GERD is associated with increased symptom severity and frequency, interference with social activities, sleep disturbance, higher levels of comorbidity, and psychological distress. Patients are less likely to consult if they feel that their doctor would trivialise their symptoms[4]. GERD has a negative impact on HRQoL being involved factors such as female gender, increased body mass index and nocturnal symptoms[5]. Nevertheless, when symptoms are properly treated, HRQoL improves in most of the cases. Thus, in a 5-year follow-up study of a large GERD population under routine care only a small minority of patients reported a clinically relevant decrease in HRQoL[32].

Although several clinical practice guidelines for GERD have been developed and published, to our knowledge, their clinical impact on gastroenterologists practice has not been evaluated. On the other hand, it is known that current GERD guidelines are infrequently used by primary care physicians. It has been shown that among 352 practitioners from 17 countries only 33% used an international and 14% used a national guideline in managing GERD patients[33]. However, in a retrospective Australian study it was shown a significant improvements in the diagnosis and management of GERD after a clinical guideline distribution and a 3-year self-audit process revealed a decrease in use of endoscopy, improved identification of risk factors, increase in recommendations for patient weight loss and reduction in use of medications that may exacerbate reflux symptoms[34]. Regarding antisecretory therapy it is well accepted that these medication are frequently overprescribed; when concordance between use of PPIs and prescribing guidelines was evaluated drug utilisation data indicated widespread use of PPIs outside current prescribing guidelines[35]. Another study tried to evaluate variability in dyspepsia management among Italian general practitioners; it was found that 44% of endoscopies prescribed for uninvestigated patients (more than half complaining of GERD symptoms) did not comply with the European Society for Primary Care Gastroenterology guideline[36].

In conclusion, compliance with the clinical practice guidelines for GERD by Spanish gastroenterologists is quite good, although a trend to indicate endoscopy in patients older than 50 years without alarm symptoms and treatments with higher PPI doses and longer duration than recommended was observed. Diagnosis of severe esophagitis is extremely infrequent, even in selected patients for endoscopy. Therapeutic response trended to be better when guideline recommendations were followed.

Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most prevalent gastrointestinal disorders in the general population. GERD diagnosis is made mainly according to the presence of symptoms, especially heartburn and/or regurgitation. An effective management strategy is particularly important because GERD imposes a significant burden of illness. For that purpose several clinical practice guidelines have been developed by different medical societies and expert consensus meetings. However, the impact of these recommendations on the behaviour of physicians has generally been limited.

It is a prospective, observational and multicentre study evaluating 301 patients with typical symptoms of GERD who should be managed in accordance with guidelines and were attended by gastroenterologists in daily practice. Diagnostic and therapeutic decisions should be made based on specific recommendations of the Spanish clinical practice guideline for GERD which is a widely disseminated and well known instrument among Spanish in digestive disease specialists.

The main findings of this study can be summarized as follows: Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was requested in 41% of patients, mainly because of the presence of alarm symptoms but also because of age over 50 years without alarm symptoms. Severe esophagitis was infrequently diagnosed even though patients were selected for endoscopy.

In almost all cases (99%), treatment with Adherence for proton pump inhibitor (PPIs) was prescribed, in the majority of cases (80%) in accordance with doses recommended in the guidelines (lower doses were prescribed in only 5% of cases and higher doses in 15%). Adherence regarding duration of PPI therapy was lower (69%) and most non-compliant behaviours were related to prolonged duration of treatment in patients with mild esophagitis or in those in which endoscopy was not performed.

Response to PPI treatment was higher in patients treated with doses of PPIs recommended in the clinical practice guidelines as compared with patients receiving other doses, although the difference was not statistically significant (95% vs 85%).

Treatment practice guidelines are helpful in securing patients uniform treatment regardless of where they seek help. Such guidelines are of no use, however, if they are not followed. A study of adherence to guidelines is thus of significant importance. The presentation of the study is concise, and was approved by relevant ethics committees.

Peer reviewer: Jose Liberato Ferreira Caboclo, Professor, Department of Surgery, Institution of FAMERP, Rua Antônio de Godoy, 4120 São José do Rio Preto, Brazil

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1256] [Cited by in RCA: 1261] [Article Influence: 63.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Moayyedi P, Talley NJ. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Lancet. 2006;367:2086-2100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ponce J, Vegazo O, Beltrán B, Jiménez J, Zapardiel J, Calle D, Piqué JM; Iberge Study Group. Prevalence of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in Spain and associated factors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:175-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hungin AP, Hill C, Raghunath A. Systematic review: frequency and reasons for consultation for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:331-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ponce J, Beltrán B, Ponce M, Zapardiel J, Ortiz V, Vegazo O, Nuevo J; Members of the IBERGE study group. Impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease on the quality of life of Spanish patients: the relevance of the biometric factors and the severity of symptoms. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:620-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mason J, Hungin AP. Review article: gastro-oesophageal reflux disease--the health economic implications. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22 Suppl 1:20-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wahlqvist P, Reilly MC, Barkun A. Systematic review: the impact of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease on work productivity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:259-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rey E, Moreno Elola-Olaso C, Rodríguez Artalejo F, Díaz-Rubio M. Impact of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms on health resource usage and work absenteeism in Spain. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2006;98:518-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Revicki DA, Wood M, Maton PN, Sorensen S. The impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Am J Med. 1998;104:252-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kulig M, Leodolter A, Vieth M, Schulte E, Jaspersen D, Labenz J, Lind T, Meyer-Sabellek W, Malfertheiner P, Stolte M. Quality of life in relation to symptoms in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-- an analysis based on the ProGERD initiative. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:767-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Orlando RC, Monyak JT, Silberg DG. Predictors of heartburn resolution and erosive esophagitis in patients with GERD. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:2091-2102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pace F, Negrini C, Wiklund I, Rossi C, Savarino V. Quality of life in acute and maintenance treatment of non-erosive and mild erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:349-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wiklund I, Talley NJ. Update on health-related quality of life in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2003;3:341-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wiklund I. Review of the quality of life and burden of illness in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis. 2004;22:108-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Grupo de trabajo de la guÃa de práctica clÃnica sobre ERGE . Manejo del paciente con enfermedad por reflujo gastro-esofágico (ERGE). GuÃa de Práctica ClÃnica. Actualización 2007. Asociación Española de GastroenterologÃa, Sociedad Española de Medicina de Familia y Comunitaria y Centro Cochrane Iberoamericano. 2007; Available from: http://www.guiasgastro.net/cgi-bin/wdbcgi.exe/gastro/guia_completa.portada?pident=2. |

| 16. | Katelaris P, Holloway R, Talley N, Gotley D, Williams S, Dent J. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in adults: Guidelines for clinicians. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:825-833. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Moraes-Filho J, Cecconello I, Gama-Rodrigues J, Castro L, Henry MA, Meneghelli UG, Quigley E; Brazilian Consensus Group. Brazilian consensus on gastroesophageal reflux disease: proposals for assessment, classification, and management. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:241-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Armstrong D, Marshall JK, Chiba N, Enns R, Fallone CA, Fass R, Hollingworth R, Hunt RH, Kahrilas PJ, Mayrand S, Moayyedi P, Paterson WG, Sadowski D, van Zanten SJ; Canadian Association of Gastroenterology GERD Consensus Group. Canadian Consensus Conference on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in adults - update 2004. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19:15-35. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Koop H, Schepp W, Müller-Lissner S, Madisch A, Micklefield G, Messmann H, Fuchs KH, Hotz J. [Consensus conference of the DGVS on gastroesophageal reflux]. Z Gastroenterol. 2005;43:163-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Davis DA, Taylor-Vaisey A. Translating guidelines into practice. A systematic review of theoretic concepts, practical experience and research evidence in the adoption of clinical practice guidelines. CMAJ. 1997;157:408-416. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Grol R. Successes and failures in the implementation of evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice. Med Care. 2001;39:II46-II54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in RCA: 608] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wright J, Warren E, Reeves J, Bibby J, Harrison S, Dowswell G, Russell I, Russell D. Effectiveness of multifaceted implementation of guidelines in primary care. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003;8:142-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, Whitty P, Eccles MP, Matowe L, Shirran L. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8:iii-iv, 1-72. [PubMed] |

| 24. | James PA, Cowan TM, Graham RP, Majeroni BA. Family physicians' attitudes about and use of clinical practice guidelines. J Fam Pract. 1997;45:341-347. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Pace F, Riegler G, de Leone A, Dominici P, Grossi E; EMERGE Study Group. Gastroesophageal reflux disease management according to contemporary international guidelines: a translational study. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1160-1166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Adair R, Callies L, Lageson J, Hanzel KL, Streitz SM, Gantert SC. Posting guidelines: a practical and effective way to promote appropriate hypertension treatment. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31:227-232. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Ray WA, Stein CM, Byrd V, Shorr R, Pichert JW, Gideon P, Arnold K, Brandt KD, Pincus T, Griffin MR. Educational program for physicians to reduce use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs among community-dwelling elderly persons: a randomized controlled trial. Med Care. 2001;39:425-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Halm EA, Atlas SJ, Borowsky LH, Benzer TI, Singer DE. Change in physician knowledge and attitudes after implementation of a pneumonia practice guideline. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:688-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Armstrong D, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Dent J, De Dombal FT, Galmiche JP, Lundell L, Margulies M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ. The endoscopic assessment of esophagitis: a progress report on observer agreement. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:85-92. [PubMed] |

| 30. | An evidence-based appraisal of reflux disease management--the Genval Workshop Report. Gut. 1999;44 Suppl 2:S1-16. [PubMed] |

| 31. | The role of endoscopy in the management of GERD: guidelines for clinical application. From the ASGE. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:834-835. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Nocon M, Labenz J, Jaspersen D, Leodolter A, Richter K, Vieth M, Lind T, Malfertheiner P, Willich SN. Health-related quality of life in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease under routine care: 5-year follow-up results of the ProGERD study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:662-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Vakil N, Malfertheiner P, Salis G, Flook N, Hongo M. An international primary care survey of GERD terminology and guidelines. Dig Dis. 2008;26:231-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kirby CN, Piterman L, Nelson MR, Dent J. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease--impact of guidelines on GP management. Aust Fam Physician. 2008;37:73-77. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Pillans PI, Kubler PA, Radford JM, Overland V. Concordance between use of proton pump inhibitors and prescribing guidelines. Med J Aust. 2000;172:16-18. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Cardin F, Zorzi M, Furlanetto A, Guerra C, Bandini F, Polito D, Bano F, Grion AM, Toffanin R. Are dyspepsia management guidelines coherent with primary care practice? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:1269-1275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |