Published online Aug 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i31.4224

Revised: April 17, 2012

Accepted: April 20, 2012

Published online: August 21, 2012

Gastric perforation is one of the most serious complications that can occur during endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). In terms of the treatment of such perforations, we previously reported that perforations immediately observed and successfully closed with endoclips during endoscopic resection could be managed conservatively. We now report the first case in our medical facility of a gastric perforation during ESD that was ineffectively treated conservatively even after successful endoscopic closure. In December 2006, we performed ESD on a recurrent early gastric cancer in an 81-year-old man with a medical history of laparotomy for cholelithiasis. A perforation occurred during ESD that was immediately observed and successfully closed with endoclips so that ESD could be continued resulting in an en-bloc resection. Intensive conservative management was conducted following ESD, however, an endoscopic examination five days after ESD revealed dehiscence of the perforation requiring an emergency laparotomy.

- Citation: Sekiguchi M, Suzuki H, Oda I, Yoshinaga S, Nonaka S, Saka M, Katai H, Taniguchi H, Kushima R, Saito Y. Dehiscence following successful endoscopic closure of gastric perforation during endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(31): 4224-4227

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i31/4224.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i31.4224

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is now an accepted therapy for node-negative early gastric cancer (EGC). Compared to endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), ESD is often preferred because this technique provides a higher rate of successful en-bloc resections[1-7], however, the risk of complications, particularly perforations, is also higher with ESD. The incidence of perforations occurring during ESD has been reported to range from 3.5% to 6.1%[2-8]. In terms of the treatment of gastric perforations during endoscopic resection, we previously reported that perforations immediately observed and successfully closed with endoclips during endoscopic resection could be treated conservatively without the need for an emergency laparotomy[8]. We now report the first case in our medical facility of a gastric perforation during ESD of EGC which was ineffectively treated conservatively, even though it was immediately detected and successfully closed with endoclips. Laparotomy was performed five days after ESD due to dehiscence following endoscopic closure.

An 81-year-old man with a medical history of laparotomy for cholelithiasis performed in 1987 was admitted to our hospital in December 2006 for the endoscopic treatment of a recurrent EGC. He had previously undergone an initial ESD for EGC at the lesser curvature of the lower gastric body in 1999. Pathological findings revealed a well-differentiated mucosal adenocarcinoma without lymphovascular involvement. The lateral margin could not be properly evaluated, however, because an incision had inadvertently been made in the lesion during ESD. After the initial ESD, endoscopic examinations were performed periodically and a recurrent tumor 20 mm in size was detected at the site of the ESD scar in October 2006 (Figure 1A).

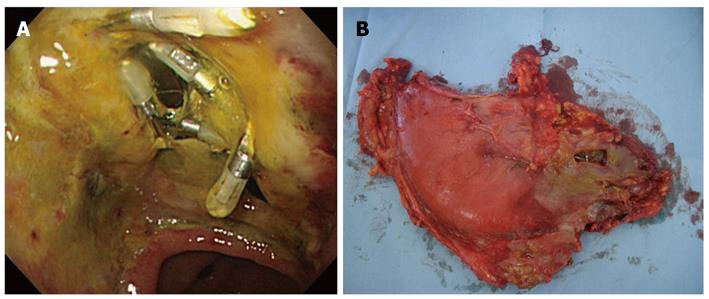

In December 2006, ESD was performed on the recurrent tumor and an oval perforation 5 mm in length occurred during the procedure at the site of extensive fibrosis from the initial ESD scar (Figure 1B). The perforation was immediately observed and successfully closed with endoclips (HX-610-090; Olympus Medical Systems Corp., Tokyo, Japan) (Figure 1C) so that the ESD could then be continued resulting in an en-bloc resection. Pathological examination revealed a well to moderately differentiated mucosal adenocarcinoma with ulcer scar from the initial ESD without lymphovascular involvement (Figure 1D, E and F). The lateral and vertical margins were negative. Following ESD, the patient was intensively managed with nasogastric suction, fasting and intravenous antibiotic therapy. The patient’s abdominal symptoms were unremarkable with no physical indications of diffuse peritonitis observed, although the patient had a fever and high C-reactive peptide level during the observation period. Despite intensive conservative management, the patient’s fever persisted and his C-reactive peptide level remained elevated at 20 mg/dL, thus we performed an endoscopic examination five days after ESD which revealed that the perforation site previously closed with endoclips had split open (Figure 2A). Since the open perforation site could not be closed endoscopically, an emergent laparotomy was performed on the same day. Surgical findings indicated that the perforation of the gastric wall extending to the omental bursa was 30 mm × 10 mm in length and the perforation site was not covered with adipose tissue (Figure 2B). Pigmentation from bile and localized findings of inflammation were observed in the omental bursa probably caused by adhesions from the previous laparotomy for cholelithiasis performed in 1987. Distal gastrectomy was performed instead of omental implantation because the gastric wall at the perforation site was fragile and the split-open perforation was relatively large in size. The patient recovered well postoperatively and was discharged 11 d after surgery with no recurrence detected as of December 2010.

We previously reported that gastric perforations which occurred during endoscopic resection could be managed conservatively with complete endoscopic closure based on the analysis of 117 patients with such perforations at our facility[8]. In our analysis, endoscopic closure with endoclips was successful in 115 of the 117 patients (98.3%) and conservative management for those 115 patients was uneventful. That is, none of the patients with successful endoscopic closure required an emergency laparotomy. In the present case, however, conservative management proved to be ineffective despite the fact that successful endoscopic closure was performed during ESD. An endoscopic examination conducted five days after ESD revealed that the perforation site previously closed successfully with endoclips had split open necessitating an emergency laparotomy.

The gastric lesion in our patient was a recurrent tumor following an initial ESD, and the existence of fibrosis at the site of ESD scar was considered to be one of the factors associated with incomplete healing of the perforation. However, on referring to our previous analysis of 46 patients who received ESDs for locally recurrent EGCs after prior endoscopic resections, perforations occurred during ESD in four patients (8.7%) with all four patients fully recovering following successful endoscopic closure with endoclips[9]. Therefore, based on those earlier reported results, we cannot conclude that the existence of fibrosis in connection with local recurrence was the only reason for failure of the healing process in the present perforation case. We speculate that there may have been another contributing cause, specifically the patient’s medical history of laparotomy for cholelithiasis. It is thought that the reason the perforation site did not heal after successful endoscopic closure was related to the adhesions resulting from the previous laparotomy. Adipose tissue did not cover the perforation site after endoscopic closure due to these adhesions, thus the perforation site was unable to heal properly. We believe that the patient’s unremarkable abdominal symptoms were also related to these adhesions as they created a closed space in the abdominal cavity thus localizing the peritonitis resulting from the gastric perforation.

Our experience in this case indicates that gastric perforations which occur during ESD cannot always be treated conservatively even after successful endoscopic closure using endoclips, particularly if the patient has a medical history of laparotomy. Consequently, we must keep this possibility in mind when performing ESD on an EGC patient with a medical history of laparotomy. In addition, we need to remember that perforation patients with a medical history of laparotomy do not always show remarkable abdominal symptoms and physical findings of diffuse peritonitis.

We wish to express our appreciation to Christopher Dix for his assistance in editing this manuscript.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Antonello Trecca, Digestive Endoscopy, Usi Group, Via Machiavelli 22, 00184 Rome, Italy

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Gotoda T, Yamamoto H, Soetikno RM. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:929-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 485] [Cited by in RCA: 507] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Oda I, Gotoda T, Hamanaka H, Eguchi T, Saito Y, Matsuda T, Bhandari P, Emura F, Saito D, Ono H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: technical feasibility, operation time and complications from a large consecutive series. Dig Endosc. 2005;17:54-58. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 333] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Onozato Y, Ishihara H, Iizuka H, Sohara N, Kakizaki S, Okamura S, Mori M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancers and large flat adenomas. Endoscopy. 2006;38:980-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Imagawa A, Okada H, Kawahara Y, Takenaka R, Kato J, Kawamoto H, Fujiki S, Takata R, Yoshino T, Shiratori Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: results and degrees of technical difficulty as well as success. Endoscopy. 2006;38:987-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kakushima N, Fujishiro M, Kodashima S, Muraki Y, Tateishi A, Omata M. A learning curve for endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric epithelial neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2006;38:991-995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Oda I, Saito D, Tada M, Iishi H, Tanabe S, Oyama T, Doi T, Otani Y, Fujisaki J, Ajioka Y. A multicenter retrospective study of endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:262-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Isomoto H, Shikuwa S, Yamaguchi N, Fukuda E, Ikeda K, Nishiyama H, Ohnita K, Mizuta Y, Shiozawa J, Kohno S. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a large-scale feasibility study. Gut. 2009;58:331-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 470] [Cited by in RCA: 520] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Minami S, Gotoda T, Ono H, Oda I, Hamanaka H. Complete endoscopic closure of gastric perforation induced by endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer using endoclips can prevent surgery (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:596-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yokoi C, Gotoda T, Hamanaka H, Oda I. Endoscopic submucosal dissection allows curative resection of locally recurrent early gastric cancer after prior endoscopic mucosal resection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:212-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |