Published online Jul 28, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i28.3721

Revised: April 12, 2012

Accepted: May 5, 2012

Published online: July 28, 2012

AIM: To determine the effective hospitalization period as the clinical pathway to prepare patients for endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).

METHODS: This is a retrospective observational study which included 189 patients consecutively treated by ESD at the National Cancer Center Hospital from May 2007 to March 2009. Patients were divided into 2 groups; patients in group A were discharged in 5 d and patients in group B included those who stayed longer than 5 d. The following data were collected for both groups: mean hospitalization period, tumor site, median tumor size, post-ESD rectal bleeding requiring urgent endoscopy, perforation during or after ESD, abdominal pain, fever above 38 °C, and blood test results positive for inflammatory markers before and after ESD. Each parameter was compared after data collection.

RESULTS: A total of 83% (156/189) of all patients could be discharged from the hospital on day 3 post-ESD. Complications were observed in 12.1% (23/189) of patients. Perforation occurred in 3.7% (7/189) of patients. All the perforations occurred during the ESD procedure and they were managed with endoscopic clipping. The incidence of post-operative bleeding was 2.6% (5/189); all the cases involved rectal bleeding. We divided the subjects into 2 groups: tumor diameter ≥ 4 cm and < 4 cm; there was no significant difference between the 2 groups (P = 0.93, χ2 test with Yates correction). The incidence of abdominal pain was 3.7% (7/189). All the cases occurred on the day of the procedure or the next day. The median white blood cell count was 6800 ± 2280 (cells/μL; ± SD) for group A, and 7700 ± 2775 (cells/μL; ± SD) for group B, showing a statistically significant difference (P = 0.023, t-test). The mean C-reactive protein values the day after ESD were 0.4 ± 1.3 mg/dL and 0.5 ± 1.3 mg/dL for groups A and B, respectively, with no significant difference between the 2 groups (P = 0.54, t-test).

CONCLUSION: One-day admission is sufficient in the absence of complications during ESD or early post-operative bleeding.

- Citation: Aoki T, Nakajima T, Saito Y, Matsuda T, Sakamoto T, Itoi T, Khiyar Y, Moriyasu F. Assessment of the validity of the clinical pathway for colon endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(28): 3721-3726

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i28/3721.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i28.3721

Conventional laparotomy is the standard treatment for early colon cancer. Subsequently, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) was developed for small polyps[1]. Analysis of surgically resected specimens revealed that in cases of early colon cancer with a depth of invasion of < 1000 μm into the submucosal layer (SM 1), no lymphatic invasion, no vascular involvement, or without a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma component, curative resection can be obtained by endoscopic treatment[2,3].

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is an advanced technique, compared with EMR, by which higher en-bloc resection and lower rates of tumor recurrence are achieved when treating large tumors > 20 mm in diameter[4-11].

In our institution, gastric ESD has been performed since 1996, and in 2002, a clinical pathway (CP) was introduced to standardize this form of intervention. This CP included a set period of hospitalization to prepare patients and to determine any sign of post-procedure complications. The efficacy of the CP in gastric ESD was then reported[12]. A similar CP was introduced for colon ESD, which involves a 5 d hospital admission, including a 1 d pre-procedure for bowel preparation. In this study, we examined the appropriateness of this hospitalization period as the CP to prepare patients for ESD and to determine any sign of post-procedure complications.

In our institution, colon ESD was introduced in 2007, and the CP was implemented in May 2007. All 189 consecutive patients who had colon ESD from May 2007 to March 2009 were included in this study. All used data were recorded in the ESD database.

Patients were divided into 2 groups: group A included patients who were discharged in 5 d and group B included patients who stayed longer than 5 d. The following data were collected for both groups: mean hospitalization period, tumor site, median tumor size, post-ESD rectal bleeding requiring urgent endoscopy, perforation during or after ESD, abdominal pain, fever above 38 °C, and blood test results positive for inflammatory markers before and after ESD.

Perforation during colon ESD was diagnosed when the abdominal cavity could be observed owing to injury of the muscle layer. Cases with no perforation, but with a deep separation of the submucosal layer, enabling the endoscopist to observe the muscle layer directly were recorded as “exposure of the muscle layer”. Late-onset bleeding was defined as the occurrence of rectal bleeding after ESD, if confirmed by urgent endoscopy. Abdominal pain was defined as the presence of tenderness following examination by a physician or by patient request for analgesia. Late-onset perforation was defined as the finding of free air on abdominal computed tomography or plain X-ray, performed owing to the complaint of abdominal pain. All complications were defined in advance and recorded in the ESD database.

Patients are admitted 1 d before the procedure at noon, and receive a low-fiber diet for lunch and dinner. For bowel preparation on the day of ESD, patients drink 3000 mL of intestinal lavage fluid [polyethylene glycol; (PEG)] over a period of 2 h in the morning. Then, the ward nurse checks their stools. If the bowel preparation is poor, patients will drink an additional 500 mL to 1000 mL of PEG. Otherwise, no food or drink is allowed on the day of the procedure or the following day. The procedure starts in the afternoon after achieving successful bowel preparation. We provide prophylactic antibiotic (cefmetazole 1.0 g, intravenously) just before the procedure.

In general, the ESD procedure is performed using a bipolar needle knife (Xeon Medical Co., Tokyo, Japan), insulation-tipped (IT) knife (Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan), HemoStat-Y (bipolar forceps for hemostasis, PENTAX, Tokyo, Japan), water jet scope (Olympus Co.), distal attachment (short ST hood, Fujifilm Co., Tokyo, Japan)[13], and a CO2 insufflation system (Olympus Co.) for all patients. The high-frequency wave device used is ICC200 (ERBE, Tubingen, Germany); to set the output power, an Endo Cut 50 W/Forced 40 W bipolar needle knife/IT knife is used; a bipolar 25 W is used for the HemoStat-Y.

Conscious sedation is performed to allow positional changes to patients during the procedure. Sedation with midazolam and pentazocine is usually started with 2 mg and 15 mg doses intravenously, respectively, and if required, additional dosing will be provided perioperatively based on the operator’s assessment. Hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan) (10 mg, intravenously) is administered immediately before the procedure and another 10 mg can be given later if needed.

The morning after the ESD, routine peripheral blood and biochemistry tests are performed. Providing there are no signs or symptoms of complications, patients will start to drink water on day 1 and have meals (rice porridge) on day 2. Patients can only walk to the restroom as they should maintain bed rest the whole day of the ESD procedure. On the next day, they can walk within the hospital ward. If there is no concern with the clinical progression, patients are allowed home on day 3. Patients are instructed to refrain from ingesting alcohol or performing exercise during the first week after hospital discharge.

The ESD procedure is performed by 6 endoscopists, all of whom began performing colon ESD after first experiencing gastric ESD cases.

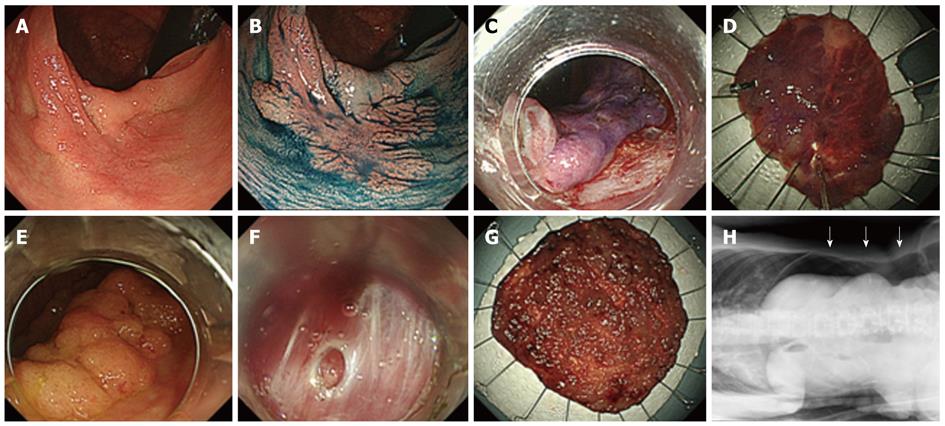

Case without complications: This is the case of a 74-year-old male patient. The tumor was of the macroscopic type, grade 0-IIa laterally spreading tumors-non-granular (LST-NG) with a diameter of 35 mm, located in the ascending colon. En-bloc resection was achieved by ESD. The total length of hospital stay was 5 d. Histological examination revealed a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, low-grade atypia with no lymphatic-vascular invasion, and the lateral and horizontal margins were negative. Curative resection was achieved (Figure 1).

Case with perforation: This is the case of a 58-year-old female patient. The tumor was of the macroscopic type, grade 0-IIa laterally spreading tumors-granular (LST-G) with a diameter of 65 mm, located in the cecum. En-bloc resection was achieved by ESD. A small perforation occurred during the ESD, which was closed by endoscopic clipping immediately after submucosal dissection around the perforation site. Abdominal X-ray showed a small amount of free air, but no abdominal pain was reported or high-grade fever (suggesting peritonitis) observed, so the patient was managed conservatively and stayed for a total of 10 d in the hospital. Histological examination revealed a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, low-grade atypia with no lymphatic-vascular invasion, and the lateral and horizontal margins were negative. Curative resection was achieved and no surgical treatment was necessary (Figure 1).

Of all the patients, 83% (156/189) could be discharged from the hospital on day 3 post-ESD (group A). On the other hand, the remaining 17% (33/189) of patients required prolonged hospitalization (group B) (Table 1). Complications were observed in 12.1% (23/189) of patients. Perforation was the most commonly observed complication, occurring in 3.7% (7/189) of patients. All the perforations occurred during the ESD procedure and none were of late-onset. They were managed with endoscopic clipping and no patient required surgical intervention. Six out of 7 patients with perforations (86%) were required to stay for more than 5 d.

| Group A | Group B | Total or average | |

| Number | 156 | 33 | 189 |

| Average hospitalization period (d) | 4.94 | 6.67 | 5.81 |

| Location of lesion | |||

| Colon (%) | 108 (69.2) | 23 (70.0) | 131 (69.0) |

| Rectum (%) | 48 (30.8) | 10 (30.3) | 58 (31) |

| Median size of lesion (mm) | 34.5 | 35 | 35 |

| Hemorrhage (%) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (12.1) | 5 (2.6) |

| Perforation (%) | 1 (0.6) | 6 (18.2) | 7 (3.7) |

| Abdominal pain (%) | 2 (1.3) | 5 (15.2) | 7 (3.7) |

| Fever > 38.0 °C (%) | 2 (1.3) | 2 (6.1) | 4 (2.1) |

| WBC (cells/μL; median) | 6800a | 7700 | 7000 |

| Hemoglobin level change pre-/post-ESD > 2.0 (%) | 5 (3.2) | 1 (3.0) | 6 (3.2) |

| CRP (mg/dL; mean) | 0.4b | 0.5 | 0.4 |

The incidence of post-operative bleeding was 2.6% (5/189); all the cases involved rectal bleeding. Five cases required hemostatic intervention and 3 of them were inpatient admissions. The period of hospitalization needed to be prolonged for 4 out of the 5 (80%) cases. Two patients had to be re-admitted to undergo emergency endoscopy due to bleeding which occurred after hospital discharge (post-discharge days 4 and 6); however, bleeding did not recur after that.

To analyze the rates of late-onset bleeding and tumor size, we divided the subjects into 2 groups: one with a tumor diameter < 4 cm (118 patients) and the other with a tumor diameter ≥ 4 cm (71 patients). The incidence of post-ESD bleeding was compared. The rates were 5.6% (4/71) for a tumor diameter < 4 cm and 4.2% (5/118) for a tumor diameter ≥ 4 cm. There was no significant difference between the 2 groups (P = 0.93, χ2 test with Yates correction).

The incidence of abdominal pain was 3.7% (7/189). All the cases occurred on the day of the procedure or the next day. Of all the patients who had abdominal pain, 70% (5/7) stayed for more than 3 d post-procedure, based on the attending physician’s assessment. The most common causes of delayed discharge from the hospital were late-onset bleeding and social reasons (7 patients each). Other complications were as follows: perforation (6 patients), exposure of the muscle layer (6 patients), abdominal pain (5 patients), fever (2 patients), and increased inflammatory reaction (1 patient).

Serum inflammatory markers were also assessed. On the day after ESD, the median white blood cell (WBC) count was 6800 ± 2280 (cells/µL; ± SD) for group A, and 7700 ± 2775 (cells/µL; ± SD) for group B, showing a statistically significant difference (P = 0.023, t-test). The mean C-reactive protein (CRP) values the day after ESD were 0.4 ± 1.3 and 0.5 ± 1.3 mg/dL for groups A and B, respectively, with no significant difference between the 2 groups (P = 0.54, t-test).

The introduction of the CP for colon ESD was demonstrated to be useful for maintaining the safety of ESD and post-procedure care[12,14-16]. Seventy-nine percent of the patients were discharged on day 3 post-procedure; they had no complications or adverse events requiring medical attention. Three percent had complications, but they did not need to stay any longer. One percent of patients were readmitted 1 week post-procedure due to bleeding.

Looking at the breakdown of the 17% of patients with CP deviation (those who stayed for more than 5 d), it was observed that most cases were due to social reasons. Taking the above into consideration, we conclude that, in the absence of complications during ESD or early post-operative bleeding, the period of admission can be safely shortened to 1 d. However, we have to consider patients’ circumstances and traveling requirements. Patients certainly need to be educated before ESD on appropriate ways of responding if symptoms of complications (particularly post-operative bleeding) occur. They may need to be advised to stay in a hotel nearby if they live far away from the endoscopy center. We have no local evidence that inpatient preparation is better than outpatient preparation. However, to avoid failure of the procedure, and patient dissatisfaction, we have included 1 d hospital stays for these reasons within our CP, particularly since the cost is very low here in Japan. On the other hand, reports from the United States and the United Kingdom have shown no differences between inpatient and outpatient preparation, and the latter situation may even be preferable[17]. Therefore, a 1 d admission for bowel preparation may not be necessary under all conditions. Omitting this admission would minimize the cost of the procedure.

As mentioned previously, the indications for colon ESD are 0-Is+IIa (LST-G) exceeding 30 mm, LST-NG exceeding 20 mm, IIc and non-lifting sign positive intramucosal lesions, and residual recurrent lesions that cannot be resected by EMR[18]. This is because the rate of SM invasion of LST-NG lesions is comparatively high, and 27% of them are multifocal invasions, making it difficult to identify the region of invasion before the procedure. Thus, accurate pathological evaluation by reliable en-bloc resection is necessary[3]. In LST-G, 84% of cases of SM invasion are in the macro-nodular area, and if the same area can be resected en-bloc, endoscopic piecemeal mucosal resection (EPMR) is also allowed. However, with a 0-Is+IIa (LST-G) exceeding 30 mm, if EPMR is eventually performed, there is the possibility that the pathological assessment of the macro-nodular component will be inaccurate; such lesions are also treated by ESD as a relative indication.

The bowel preparation for colon ESD at our institution consists of domperidone (10 mg) and mosapride citrate hydrate (15 mg) administered with 3000 mL to a maximum of 4000 mL of PEG. This is a more rigorous bowel preparation than that used for conventional colonoscopy. This is to ensure a good field of view during ESD and to prevent diffuse peritonitis due to the discharge of fecal fluid in case perforation occurs[19].

Currently, there are no fixed guidelines for antibiotics that can be administered prophylactically in colon ESD. In the field of gastroenterological surgery, there is evidence that prophylactic administration of antibiotics is useful in the prevention of wound infection, and broad-spectrum antibiotics are commonly used immediately before surgery. In the field of therapeutic endoscopy of the colon, Ishikawa et al[20] reported that if the high risk of infectious endocarditis and bacteremia are considered, the administration of antibiotics depended on the type of treatment procedure. This report was on conventional snare polypectomy and hot biopsy. With colon ESD, the risk of perforation is slightly higher than in the above procedures; therefore, we considered it appropriate to provide some form of prophylactic treatment. However, as changes in WBC and CRP level are minimal, there is the possibility that such treatment can be omitted.

We consider the bipolar system (B-knife), which is mainly used in the colon ESD procedure, to be safe[21]. Although the monopolar system is available as a backup, the IT-knife with an insulated tip that enhances safety is being used[22,23]. In other institutions, there are those that mainly use a dual-knife (Olympus Co.) with the monopolar system. Differences between such devices can create differences in the rate of complications and the method of post-ESD management.

The colon ESD performed at our institution has the indications mentioned above and is discussed in the context of the CP. The purpose of this study was to investigate the appropriateness and effectiveness of the 5 d hospitalization period, including 1 d for bowel preparation, as the CP to prepare patients for ESD and to determine any sign of post-procedure complications. However, the attending physician mainly judged the prolongation of the hospitalization period. Although there is no particularly clear standard, the attending physician usually orders the prolongation under any of the following circumstances: (1) when complications, such as perforation and bleeding, are observed; (2) when an ablation on the intrinsic muscle layer at the time of ESD is judged as invasive; and (3) when there may be problems with blood sampling or physical findings the following day. It became clear that in such a case, the time to restart ingestion of water and food was commonly prolonged. At our institution, the incidence of post-ESD bleeding following gastric ESD is approximately 5% and the CP for gastric ESD is 7 d (patients discharged on day 5 after ESD). With the introduction of the CP for colon ESD, the incidence of post-ESD bleeding was lower than gastric ESD bleeding; thus, the period of hospitalization was set at 5 d and safety could be maintained for many patients. The lesions, method and bowel preparation in colon ESD differ according to the institution; therefore, the risks of complications during and after ESD are likely to differ. Hereafter, to stratify the risks in the CP, addition of the status after resection (complete suturing) and the site of the lesion (rectum or colon) as parameters should increase safety.

There is no doubt that a 5 d hospitalization period may not be possible in many countries for financial reasons. A randomized control trial would be the best method to evaluate the necessity of post-procedure hospital admission. However, we would like to share our findings from this retrospective observational study which confirm the safety of discharging ESD patients without any complications 1 d after the procedure.

The authors are indebted to Dr. Clifford Kolba (EdD, DO, MPH, CPH) and Associate Professor Edward F Barroga (PhD) of the Department of International Medical Communications of Tokyo Medical University for their editorial review of the manuscript.

Conventional laparotomy is the standard treatment for early colon cancer. Subsequently, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) was developed for small polyps. Analysis of surgically resected specimens revealed that in cases of early colon cancer with a depth of invasion of < 1000 μm into the submucosal layer (SM 1), no lymphatic invasion, no vascular involvement, or without a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma component, curative resection can be obtained by endoscopic treatment.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is an advanced technique, compared with EMR, by which higher en-bloc resection and lower rates of tumor recurrence are achieved when treating large tumors > 20 mm in diameter.

This is a retrospective observational study which included 189 patients consecutively treated by ESD at the National Cancer Center Hospital from May 2007 to March 2009. The following data were collected for both groups: mean hospitalization period, tumor site, median tumor size, post-ESD rectal bleeding requiring urgent endoscopy, perforation during or after ESD, abdominal pain, fever above 38 °C, and blood test results positive for inflammatory markers before and after ESD. Each parameter was compared after data collection.

The lesions, method and bowel preparation in colon ESD differ according to the institution; therefore, the risks of complications during and after ESD are likely to differ. Hereafter, to stratify the risks in the clinical pathway, addition of the status after resection (complete suturing) and the site of the lesion (rectum or colon) as parameters should increase safety.

The paper covers an important topic related to the ESD procedure: the length of the hospital stay and the quality of the monitoring of the patient after the procedure. The clinical problem is well exposed, the picture is impressive and the paper opens a new area of discussion on colonic ESD.

Peer reviewers: Dr. Antonello Trecca, Digestive Endoscopy, USI Group, Via Machiavelli, 22, 00184 Rome, Italy; A Probst, Professor, Klinikum Augsburg, Med Klin 3, Stenglinstr 2, D-86156 Augsburg, Germany

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Rosenberg N. Submucosal saline wheal as safety factor in fulguration or rectal and sigmoidal polypi. AMA Arch Surg. 1955;70:120-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kitajima K, Fujimori T, Fujii S, Takeda J, Ohkura Y, Kawamata H, Kumamoto T, Ishiguro S, Kato Y, Shimoda T. Correlations between lymph node metastasis and depth of submucosal invasion in submucosal invasive colorectal carcinoma: a Japanese collaborative study. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:534-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 487] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Uraoka T, Saito Y, Matsuda T, Ikehara H, Gotoda T, Saito D, Fujii T. Endoscopic indications for endoscopic mucosal resection of laterally spreading tumours in the colorectum. Gut. 2006;55:1592-1597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 319] [Cited by in RCA: 307] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ohkuwa M, Hosokawa K, Boku N, Ohtu A, Tajiri H, Yoshida S. New endoscopic treatment for intramucosal gastric tumors using an insulated-tip diathermic knife. Endoscopy. 2001;33:221-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ono H, Kondo H, Gotoda T, Shirao K, Yamaguchi H, Saito D, Hosokawa K, Shimoda T, Yoshida S. Endoscopic mucosal resection for treatment of early gastric cancer. Gut. 2001;48:225-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1134] [Cited by in RCA: 1149] [Article Influence: 47.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 6. | Kobayashi T, Gotohda T, Tamakawa K, Ueda H, Kakizoe T. Magnetic anchor for more effective endoscopic mucosal resection. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:118-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yamamoto H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early cancers and large flat adenomas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:S74-S76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Saito Y, Emura F, Matsuda T, Uraoka T, Nakajima T, Ikematsu H, Gotoda T, Saito D, Fujii T. A new sinker-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:297-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Saito Y, Uraoka T, Matsuda T, Emura F, Ikehara H, Mashimo Y, Kikuchi T, Fu KI, Sano Y, Saito D. Endoscopic treatment of large superficial colorectal tumors: a case series of 200 endoscopic submucosal dissections (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:966-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Saito Y, Uraoka T, Yamaguchi Y, Hotta K, Sakamoto N, Ikematsu H, Fukuzawa M, Kobayashi N, Nasu J, Michida T. A prospective, multicenter study of 1111 colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissections (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1217-1225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 591] [Cited by in RCA: 593] [Article Influence: 39.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Saito Y, Sakamoto T, Fukunaga S, Nakajima T, Kiriyama S, Matsuda T. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for colorectal tumors. Dig Endosc. 2009;21 Suppl 1:S7-S12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hirasaki S, Tanimizu M, Moriwaki T, Hyodo I, Shinji T, Koide N, Shiratori Y. Efficacy of clinical pathway for the management of mucosal gastric carcinoma treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection using an insulated-tip diathermic knife. Intern Med. 2004;43:1120-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yamamoto H, Kawata H, Sunada K, Sasaki A, Nakazawa K, Miyata T, Sekine Y, Yano T, Satoh K, Ido K. Successful en-bloc resection of large superficial tumors in the stomach and colon using sodium hyaluronate and small-caliber-tip transparent hood. Endoscopy. 2003;35:690-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 288] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | al-Shaqha WM, Zairi M. Re-engineering pharmaceutical care: towards a patient-focused care approach. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv. 2000;13:208-217. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Podila PV, Ben-Menachem T, Batra SK, Oruganti N, Posa P, Fogel R. Managing patients with acute, nonvariceal gastrointestinal hemorrhage: development and effectiveness of a clinical care pathway. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:208-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pfau PR, Cooper GS, Carlson MD, Chak A, Sivak MV, Gonet JA, Boyd KK, Wong RC. Success and shortcomings of a clinical care pathway in the management of acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:425-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Anderson E, Baker JD. Bowel preparation effectiveness: inpatients and outpatients. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2007;30:400-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Saito Y, Fukuzawa M, Matsuda T, Fukunaga S, Sakamoto T, Uraoka T, Nakajima T, Ikehara H, Fu KI, Itoi T. Clinical outcome of endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic mucosal resection of large colorectal tumors as determined by curative resection. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:343-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 381] [Cited by in RCA: 428] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hendry PO, Jenkins JT, Diament RH. The impact of poor bowel preparation on colonoscopy: a prospective single centre study of 10,571 colonoscopies. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:745-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ishikawa H, Akedo I, Minami T, Shinomura Y, Tojo H, Otani T. Prevention of infectious complications subsequent to endoscopic treatment of the colon and rectum. J Infect Chemother. 1999;5:86-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sano Y, Fu KI, Saito Y, Doi T, Hanafusa M, Fujii S, Fujimori T, Ohtsu A. A newly developed bipolar-current needle-knife for endoscopic submucosal dissection of large colorectal tumors. Endoscopy. 2006;38 Suppl 2:E95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kondo H, Gotoda T, Ono H, Oda I, Kozu T, Fujishiro M, Saito D, Yoshida S. Percutaneous traction-assisted EMR by using an insulation-tipped electrosurgical knife for early stage gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:284-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gotoda T, Kondo H, Ono H, Saito Y, Yamaguchi H, Saito D, Yokota T. A new endoscopic mucosal resection procedure using an insulation-tipped electrosurgical knife for rectal flat lesions: report of two cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:560-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |