Published online Jun 14, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i22.2821

Revised: September 24, 2011

Accepted: April 12, 2012

Published online: June 14, 2012

AIM: To estimate the incidence of collagenous colitis (CC) in southern Sweden during 2001-2010.

METHODS: Cases were identified by searching for CC in the diagnostic registers at the Pathology Departments in the county of Skåne. The catchment area comprised the south-west part of the county (394 307 inhabitants in 2010) and is a mixed urban and rural type with limited migration. CC patients that had undergone colonoscopy during the defined period and were living in this area were included in the study regardless of where in Skåne they had been diagnosed. Medical records were scrutinized and uncertain cases were reassessed to ensure that only newly diagnosed CC cases were included. The diagnosis of CC was based on both clinical and histopathological criteria. The clinical criterion was non-bloody watery diarrhoea. The histopathological criteria were a chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria, a thickened subepithelial collagen layer ≥ 10 micrometers (μm) and epithelial damage such as flattening and detachment.

RESULTS: During the ten year period from 2001-2010, 198 CC patients in the south-west part of the county of Skåne in southern Sweden were newly diagnosed. Of these, 146 were women and 52 were men, i.e., a female: male ratio of 2.8:1. The median age at diagnosis was 71 years (range 28-95/inter-quartile range 59-81); for women median age was 71 (range 28-95) years and was 73 (range 48-92) years for men. The mean annual incidence was 5.4/105 inhabitants. During the time periods 2001-2005 and 2006-2010, the mean annual incidence rates were 5.4/105 for both periods [95% confidence interval (CI): 4.3-6.5 in 2001-2005 and 4.4-6.4 in 2006-2010, respectively, and 4.7-6.2 for the whole period]. Although the incidence varied over the years (minimum 3.7 to maximum 6.7/105) no increase or decrease in the incidence could be identified. The odds ratio (OR) for CC in women compared to men was estimated to be 2.8 (95% CI: 2.0-3.7). The OR for women 65 years of age or above compared to below 65 years of age was 6.9 (95% CI: 5.0-9.7), and for women 65 years of age or above compared to the whole group the OR was 4.7 (95% CI: 3.6-6.0). The OR for age in general, i.e., above or 65 years of age compared to those younger than 65 was 8.3 (95% CI: 6.2-11.1). During the last decade incidence figures for CC have also been reported from Calgary, Canada during 2002-2004 (4.6/105) and from Terrassa, Spain during 2004-2008 (2.6/105). Our incidence figures from southern Sweden during 2001-2010 (5.4/105) as well as the incidence figures presented in the studies during the 1990s (Terrassa, Spain during 1993-1997 (2.3/105), Olmsted, United States during 1985-2001 (3.1/105), Örebro, Sweden during 1993-1998 (4.9/105), and Iceland during 1995-1999 (5.2/105) are all in line with a north-south gradient, something that has been suggested before both for CC and inflammatory bowel disease.

CONCLUSION: The observed incidence of CC is comparable with previous reports from northern Europe and America. The incidence is stable but the female: male ratio seems to be decreasing.

- Citation: Vigren L, Olesen M, Benoni C, Sjöberg K. An epidemiological study of collagenous colitis in southern Sweden from 2001-2010. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(22): 2821-2826

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i22/2821.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i22.2821

In 1976, a pathology colleague at our hospital, Clas G Lindström, received rectal biopsies for a second opinion. The patient was a 48-year-old woman with chronic non-bloody watery diarrhoea and based on his observations he described the first ever case of collagenous colitis (CC)[1]. In his case report, Lindström actually described a typical case of CC, i.e., a middle-aged woman with chronic non-bloody watery diarrhoea. Independently, a group from Canada also reported this entity[2]. Other common CC symptoms include abdominal pain, weight loss and faecal incontinence[3-5]. The diagnosis of CC can only be established by microscopic examination of colonic mucosal biopsies. Endoscopy usually reveals a macroscopically normal mucosa, although some changes may be seen with special staining methods, e.g. altered vessel formation and disturbed pattern of the mucous membrane[6,7]. Histopathologically, CC is characterised by a thickened subepithelial collagen layer, combined with a chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria and surface epithelial damage. In 1989, Lazenby[8] described lymphocytic colitis (LC), a similar condition clinically and histopathologically, but without a thickened subepithelial collagen layer. Collagenous colitis and LC are included in the umbrella term microscopic colitis (MC).

About 10% of patients investigated for non-bloody diarrhoea and with a macroscopically normal colonic mucosa are diagnosed with MC[8-11] even though an incidence as high as 29% has been observed[12]. These figures indicate that the condition could be prevalent. Incidence data on CC is available from the mid 1990s[13]. Initially, CC was considered to be a rare disease, but with time it has become evident that the incidence of CC is higher than was first anticipated.

The aim of this study was to estimate the incidence of CC in a well-defined population in southern Sweden during the ten year period from 2001-2010.

The catchment area in this study comprised the south-west part of the county of Skåne (the county had 1 243 329 inhabitants on December 31st, 2010). The catchment area (including the cities of Malmö and Trelleborg, and the villages Vellinge and Svedala) is a mixed urban and rural type with limited migration (from 2001 to 2010 the population increased by 13%, from 349 693 to 394 307 inhabitants). The town of Malmö has the third largest population in Sweden, while Trelleborg is a small town. Vellinge and Svedala are smaller communities. In the catchment area there are two hospitals, one in Malmö and one in Trelleborg. Colonoscopy is carried out at both hospitals as well as by some private practitioners. There is only one Pathology Department in the catchment area (in Malmö) and all mucosal colonic biopsy specimens from the hospitals in Malmö and Trelleborg as well as from the private practitioners are sent to this Pathology Department.

Patients living in the catchment area who underwent colonoscopy due to watery diarrhoea and were diagnosed with CC from 2001-2010, were included in the study. Cases were identified by searching for the diagnosis of CC in the diagnostic register at the Pathology Department in Malmö. The medical records for the identified CC patients were subsequently scrutinized for clinical data to ensure that only newly diagnosed cases were included.

Histopathologically uncertain cases as well as cases not diagnosed by an experienced gastrointestinal pathologist were reassessed by a pathologist specialised in gastrointestinal pathology (Martin Olesen). Patients not fulfilling the histopathological criteria for CC were excluded. Patients with a histopathological diagnosis of “unspecific chronic inflammation” and with watery diarrhoea were also re-evaluated to identify putative missed CC cases.

All CC patients living in the catchment area were included regardless of where in Skåne they were diagnosed. To eliminate the risk of missing patients living in the catchment area during the study period in 2001-2010, but having had a diagnostic colonoscopy with biopsies in adjacent areas outside the catchment area (i.e., in the remaining area of Skåne), the diagnostic registers at the other three Pathology Departments in Skåne were scrutinized for cases with CC. In accordance with this, patients not living in the catchment area from 2001-2010, but diagnosed at our Pathology Department were excluded.

All information regarding the size of the population as well as age and sex distribution was obtained from Statistics Sweden, the central bureau for national socioeconomic information.

The diagnosis of CC was based on both clinical and histopathological criteria. The clinical criterion was non-bloody watery diarrhoea. The histopathological criteria were as follows: (1) A chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria; (2) A thickened subepithelial collagen layer ≥ 10 micrometers (μm); and (3) Epithelial damage such as flattening and detachment.

The subepithelial collagen layer was measured with an ocular micrometer in a well orientated section of the mucosa. Measurement of the subepithelial collagen layer was obtained using special stains for collagen fibres (Masson’s trichrome or van Gieson) and/or reticulin fibres (Sirius red).

For the purpose of calculating the incidence rate, it was assumed that the entire population in the catchment area was at risk. The incidence calculations were based on the date of diagnosis and 95% confidence interval (CI): were included. The calculation of mean annual incidence/100 000 as well as age-related incidence was based on the number of inhabitants on December 31st of each year. Data on the studied population are presented as median and range/inter-quartile range (IQ) (25th-75th percentiles). Comparisons between groups were carried out using odds ratios (OR) and corresponding 95% CI.

The study was approved by the Committee of Research Ethics at Lund University.

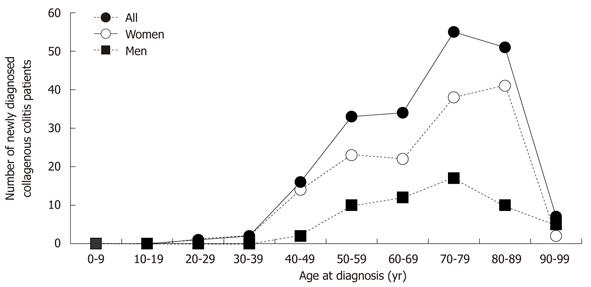

In the ten year period from 2001-2010, 198 CC patients were newly diagnosed. Of these, 146 were women and 52 were men (female:male ratio 2.8:1). The median age at diagnosis was 71 years (range 28-95/IQ 59-81); for women median age was 71 (range 28-95) years and was 73 (range 48-92) years for men (Figure 1).

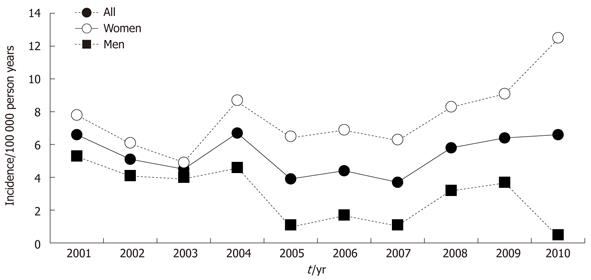

During the time periods 2001-2005 and 2006-2010, the mean annual incidence rates were 5.4/105 for both periods (95% CI: 4.3-6.5 in 2001-2005 and 4.4-6.4 in 2006-2010, respectively, and 4.7-6.2 for the whole period). Consequently, although the incidence rates varied over the years (minimum 3.7 to maximum 6.7/105) no increase or decrease could be identified (Figure 2, Tables 1 and 2).

| Year | Annual incidence/105 (total) | Annual incidence/105 (women) |

| 2001 | 6.6 | 7.8 |

| 2002 | 5.1 | 6.1 |

| 2003 | 4.5 | 4.9 |

| 2004 | 6.7 | 8.7 |

| 2005 | 3.9 | 6.5 |

| 2006 | 4.4 | 6.9 |

| 2007 | 3.7 | 6.3 |

| 2008 | 5.8 | 8.3 |

| 2009 | 6.4 | 9.1 |

| 2010 | 6.6 | 12.5 |

| Ref. | Time period | N | Mean annual incidence1 | Female:male ratio |

| Raclot et al[32] | 1987-1992 | 0.6 | ||

| Bohr et al[13] | 1984-1993 | 30 | 1.8 | 9 |

| Pardi et al[14] | 1985-2001 | 46 | 3.1 | 4.4 |

| Fernández-Bañares et al[10] | 1993-1997 | 23 | 2.3 | 4.8 |

| Olesen et al[11] | 1993-1998 | 51 | 4.9 | 7.5 |

| Agnarsdottir et al[15] | 1995-1999 | 71 | 5.2 | 7.9 |

| Williams et al[16] | 2002-2004 | 75 | 4.6 | |

| Fernández-Bañares et al[17] | 2004-2008 | 40 | 2.6 | 3.4 |

| Present study | 2001-2010 | 198 | 5.4 | 2.8 |

The OR for CC in women compared to men was estimated to be 2.8 (95% CI: 2.0-3.7). The OR for women 65 years of age or above compared to below 65 years of age was 6.9 (95% CI: 5.0-9.7), and for women 65 years of age or above compared to the whole group the OR was 4.7 (95% CI: 3.6-6.0). The OR for age in general, i.e., above or 65 years of age compared to those younger than 65 was 8.3 (95% CI: 6.2-11.1).

Information on the incidence of CC is available from one centre in the United States, one in Canada and a few in Europe (including Örebro in the central part of Sweden). Our study has added information on the epidemiology of CC in the southern part of Sweden. We report a mean annual incidence of CC of 5.4/105 for the period 2001-2010, which is in line with previous data from Örebro in central Sweden during 1993-1998 (4.9/105)[11], and is in accordance with the reported figures from Olmsted County, Minnesota, United States from 1997-2001 (6.2/105)[14], Iceland from 1995-1999 (5.2/105)[15]and Calgary, Alberta, Canada from 2002-2004 (4.6/105)[15,16]. However, these findings are in contrast to the incidence reported from Terrassa, Spain during 2004-2008 (2.6/105)[17](Table 2). Although the findings are not contradictory or novel in comparison with, for example, the report from Örebro[11], the number of cases is large and the epidemiological information is updated in a new region that has not been studied before.

Most relevant from the Swedish perspective, are the extensive investigations from Örebro, in the central part of Sweden, where the incidence rates were calculated over a 15-year period from 1984-1998. An increased incidence of CC from 1.8/105 in 1984-1993 to 3.7/105 in 1993-1995 and 6.1/105 in 1996-1998 was reported[11,12]. In Spain, the incidence increased from 1.1/105 in 1993-1997 to 2.6/105 in 2004-2008[10,17]. In accordance with these reported increases, the Minnesota data from 1985 to 2001 show the same phenomenon. In 1985-1997, the incidence was 1.6/105 compared to 7.1/105 in 1998-2001[14]. An explanation for these reported increases in incidence rates could be an increased awareness of CC and more frequent use of colonoscopies with biopsies in the diagnostic procedure, although there was probably a true increase in incidence as well. The incidence of other gastrointestinal disorders such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease and coeliac disease has increased in the Western world during the last few decades[18-21] and the influence of a common environmental factor (or several) cannot be ruled out. Interestingly, coeliac disease- similar to CC-has also increased over the last few decades and these diseases are related to each other[22]. Lansoprazole and other proton pump inhibitors are, in addition to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, associated with a higher risk of CC[22-30]. The possibility that other factors such as infectious agents and components in our food could contribute to the increased incidence has also been contemplated.

The time period of ten years in our study is fairly long and provides information on possible fluctuations in the CC incidence rate in our catchment area during the period 2001-2010. Despite some variation in the annual incidence we did not observe any significant increase or decreases in the incidence during the study period. This is in contrast with the reported increases mentioned above. The stable incidence in our study might be due to the fact that CC was described at our hospital in Malmö by Lindström as early as 1976, i.e., 35 years ago. Accordingly, CC has been known among medical doctors in this area for more than 30 years, and as a consequence regular use of colonoscopies, with multiple biopsies throughout the entire length of the colon, has been standard in the diagnostic procedure of chronic watery diarrhoea for a long time. Furthermore, there has been a close clinical and scientific collaboration between gastroenterologists and pathologists within the field of CC.

During the last decade incidence figures for CC have been reported from Canada during 2002-2004 (4.6/105) and from Spain during 2004-2008 (2.6/105)[16,17]. There was a considerable difference in the incidence of CC in these studies despite the fact that the study periods were similar and relatively recent. Fernandez-Banares highlighted the possibility of a north-south gradient with a higher incidence further north compared to those closer to the equator[17]. This possibility is further strengthened by our study. A larger number of studies have been listed in Table 2 to illustrate this phenomenon. This is also in line with the north-south gradient suggested for inflammatory bowel disease[31].

The female: male ratio in the present study (2.8:1) was significantly lower than that in previous reports (Table 2). The previous Swedish studies from Örebro reported a female: male ratio as high as 9 and 7.5 in 1984-1993 and 1993-1998, respectively. Interestingly, it might very well be that the ratio may have decreased over the years as indicated in Table 2, which to the best of our knowledge, has not been reported before.

The OR calculated for age in general, women compared to men, older women compared to younger women, and older women compared to the whole group indicated that the risk of acquiring CC is higher in older persons, especially women, which is in line with observations from several other studies. Based on the levels for the different OR it could be speculated that age (OR 8.3 for age in general and 6.9 for older women) contributes more than sex (OR 2.8) to the risk of CC.

The geographical area studied, the south-west part of Skåne, a county in southern Sweden, has several advantages for carrying out epidemiological studies. The organisation for medical care is well defined, with two hospitals and one Pathology Department. The catchment area per se is also well defined. In addition, the migration rate in the area is limited. Furthermore, the use of personal identity numbers in Sweden that follow the individual throughout her or his entire life span makes it possible to identify every individual with CC in the region and to determine whether she or he lives within the catchment area. Accordingly, the conditions for conducting an epidemiologic CC study in Sweden are favourable. Another strength of this CC study was the precautions taken to identify patients who belonged to the catchment area but who had been diagnosed in another part of the county, by scrutinizing residents with CC at all Pathology Departments in Skåne. This study is also fairly large with 198 identified CC cases during the period (Table 2).

In conclusion, we observed a mean annual incidence of CC in southern Sweden of 5.4/105, in line with previous data. In contrast to previously reported increases in the incidence rate, we report a stable incidence during the ten year study period from 2001-2010. The female: male ratio (2.8:1) was lower than previously reported. Based on data from available studies it seems that the female: male ratio is decreasing. In accordance with previously presented data it also seems that CC is more common in northern countries.

We thank The Swedish Energy Agency, Region Skåne and Kock’s Foundation in Trelleborg for financial support. We are grateful to MS Gloria Stenberg for linguistic assistance.

Collagenous colitis (CC) predominantly affects middle-aged women and results in chronic watery diarrhoea. It has become evident that the incidence of CC is much higher than was first anticipated.

Information on the incidence of CC is available from one centre in the United States, one in Canada and a few in Europe. The incidence of CC in Örebro, in central Sweden, was 4.9/105 from 1993-1998. This level is in accordance with the reported figures from Olmsted County, Minnesota, United States during 1997-2001 (6.2/105), Iceland during 1995-1999 (5.2/105) and Calgary, Alberta, Canada during 2002-2004 (4.6/105). However, these findings are in contrast to the incidence reported from Terrassa, Spain in 2004-2008 (2.6/105), which is much lower.

The study added information on the epidemiology of CC in the southern part of Sweden. The authors observed a mean annual incidence of CC in southern Sweden of 5.4/105, which is in line with previous data. In contrast to previously reported increases in the incidence rate, the authors report a stable incidence in the ten year study period from 2001-2010. The female: male ratio (2.8:1) was lower than previously reported. Based on data from available studies it seems that the female:male ratio is decreasing. In accordance with previously presented data, it also seems that CC is more common in northern countries.

During the 25 years since the first epidemiological study, the incidence of CC increased from 1.8 to 5.4/100 000 inhabitants. It now seems to have levelled out. At the same time the female: male ratio has decreased. Consequently, more men (in relation to women) have been affected in recent years. Despite this, age is associated with a higher OR for disease than sex. The risk of disease is higher in northern than in southern Europe. The following remain to be clarified: Why the incidence is no longer increasing, why the female: male ratio has decreased and why people in northern Europe have a higher risk of disease. Environmental factors could have a substantial impact on CC; smoking, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and proton pump inhibitors are known triggers but it can not be ruled out that several other factors are responsible for the high incidence of CC.

Incidence represents how many persons are affected by a certain disease/year in each group of 100 000 inhabitants within a defined area. Collagenous colitis mean inflammation in the large intestine that is predominantly visible via examination with a microscope, where the collagen layer can be observed in the epithelium. The disease results in chronic watery diarrhoea.

The manuscript is relatively well written, and the results are moderately interesting.

Peer reviewers: Hugh J Freeman, Professor, MD, CM, FRCPC, FACP, Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia, UBC Hospital 2211 Wesbrook Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 1W5, Canada; Shotaro Nakamura, MD, Department of Medicine and Clinical Science, Kyushu University, Maidashi 3-1-1, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka 812-8582, Japan

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Lindström CG. 'Collagenous colitis' with watery diarrhoea--a new entity? Pathol Eur. 1976;11:87-89. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Freeman HJ, Weinstein WM, Shnitka TK, Wensel RH, Sartor VE. Watery diarrhea syndrome associated with a lesion of the colonic basement membrane-lamina propria interface. Ann Royal Coll Phys Surg Can. 1976;9:45. |

| 3. | Bohr J, Tysk C, Eriksson S, Abrahamsson H, Järnerot G. Collagenous colitis: a retrospective study of clinical presentation and treatment in 163 patients. Gut. 1996;39:846-851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fernández-Bañares F, Salas A, Esteve M, Espinós J, Forné M, Viver JM. Collagenous and lymphocytic colitis. evaluation of clinical and histological features, response to treatment, and long-term follow-up. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:340-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Freeman HJ. Collagenous mucosal inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:338-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cimmino DG, Mella JM, Pereyra L, Luna PA, Casas G, Caldo I, Popoff F, Pedreira S, Boerr LA. A colorectal mosaic pattern might be an endoscopic feature of collagenous colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:139-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sato S, Benoni C, Tóth E, Veress B, Fork FT. Chromoendoscopic appearance of collagenous colitis--a case report using indigo carmine. Endoscopy. 1998;30:S80-S81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lazenby AJ, Yardley JH, Giardiello FM, Jessurun J, Bayless TM. Lymphocytic ("microscopic") colitis: a comparative histopathologic study with particular reference to collagenous colitis. Hum Pathol. 1989;20:18-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Erdem L, Yildirim S, Akbayir N, Yilmaz B, Yenice N, Gultekin OS, Peker O. Prevalence of microscopic colitis in patients with diarrhea of unknown etiology in Turkey. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4319-4323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fernández-Bañares F, Salas A, Forné M, Esteve M, Espinós J, Viver JM. Incidence of collagenous and lymphocytic colitis: a 5-year population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:418-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Olesen M, Eriksson S, Bohr J, Järnerot G, Tysk C. Microscopic colitis: a common diarrhoeal disease. An epidemiological study in Orebro, Sweden, 1993-1998. Gut. 2004;53:346-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Essid M, Kallel S, Ben Brahim E, Chatti S, Azzouz MM. [Prevalence of the microscopic colitis to the course of the chronic diarrhea: about 150 cases]. Tunis Med. 2005;83:284-287. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Bohr J, Tysk C, Eriksson S, Järnerot G. Collagenous colitis in Orebro, Sweden, an epidemiological study 1984-1993. Gut. 1995;37:394-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pardi DS, Loftus EV, Smyrk TC, Kammer PP, Tremaine WJ, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ, Sandborn WJ. The epidemiology of microscopic colitis: a population based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gut. 2007;56:504-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Agnarsdottir M, Gunnlaugsson O, Orvar KB, Cariglia N, Birgisson S, Bjornsson S, Thorgeirsson T, Jonasson JG. Collagenous and lymphocytic colitis in Iceland. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1122-1128. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Williams JJ, Kaplan GG, Makhija S, Urbanski SJ, Dupre M, Panaccione R, Beck PL. Microscopic colitis-defining incidence rates and risk factors: a population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:35-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fernández-Bañares F, Salas A, Esteve M, Pardo L, Casalots J, Forné M, Espinós JC, Loras C, Rosinach M, Viver JM. Evolution of the incidence of collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis in Terrassa, Spain: a population-based study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1015-1020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chouraki V, Savoye G, Dauchet L, Vernier-Massouille G, Dupas JL, Merle V, Laberenne JE, Salomez JL, Lerebours E, Turck D. The changing pattern of Crohn's disease incidence in northern France: a continuing increase in the 10- to 19-year-old age bracket (1988-2007). Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1133-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Herrinton LJ, Liu L, Lewis JD, Griffin PM, Allison J. Incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in a Northern California managed care organization, 1996-2002. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1998-2006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jussila A, Virta LJ, Kautiainen H, Rekiaro M, Nieminen U, Färkkilä MA. Increasing incidence of inflammatory bowel diseases between 2000 and 2007: a nationwide register study in Finland. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:555-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lakatos PL, David G, Pandur T, Erdelyi Z, Mester G, Balogh M, Szipocs I, Molnar C, Komaromi E, Kiss LS. IBD in the elderly population: results from a population-based study in Western Hungary, 1977-2008. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:5-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Freeman HJ. Collagenous colitis as the presenting feature of biopsy-defined celiac disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:664-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bjarnason I, Hayllar J, MacPherson AJ, Russell AS. Side effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on the small and large intestine in humans. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1832-1847. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Chande N, Driman DK. Microscopic colitis associated with lansoprazole: report of two cases and a review of the literature. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:530-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fernández-Bañares F, Esteve M, Espinós JC, Rosinach M, Forné M, Salas A, Viver JM. Drug consumption and the risk of microscopic colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:324-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Giardiello FM, Hansen FC, Lazenby AJ, Hellman DB, Milligan FD, Bayless TM, Yardley JH. Collagenous colitis in setting of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and antibiotics. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:257-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Riddell RH, Tanaka M, Mazzoleni G. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as a possible cause of collagenous colitis: a case-control study. Gut. 1992;33:683-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Thomson RD, Lestina LS, Bensen SP, Toor A, Maheshwari Y, Ratcliffe NR. Lansoprazole-associated microscopic colitis: a case series. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2908-2913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wilcox GM, Mattia A. Collagenous colitis associated with lansoprazole. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:164-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wilcox GM, Mattia AR. Microscopic colitis associated with omeprazole and esomeprazole exposure. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:551-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Shivananda S, Lennard-Jones J, Logan R, Fear N, Price A, Carpenter L, van Blankenstein M. Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease across Europe: is there a difference between north and south? Results of the European Collaborative Study on Inflammatory Bowel Disease (EC-IBD). Gut. 1996;39:690-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 684] [Cited by in RCA: 666] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Raclot G, Queneau PE, Ottignon Y, Angonin R, Monnot B, Leroy M, Devalland C, Girard V, Carbillet JP, Carayon P. Incidence of collagenous colitis. A retrospective study in the east of France. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:A23. |